Adolescence in One Take

By Kaleem Aftab

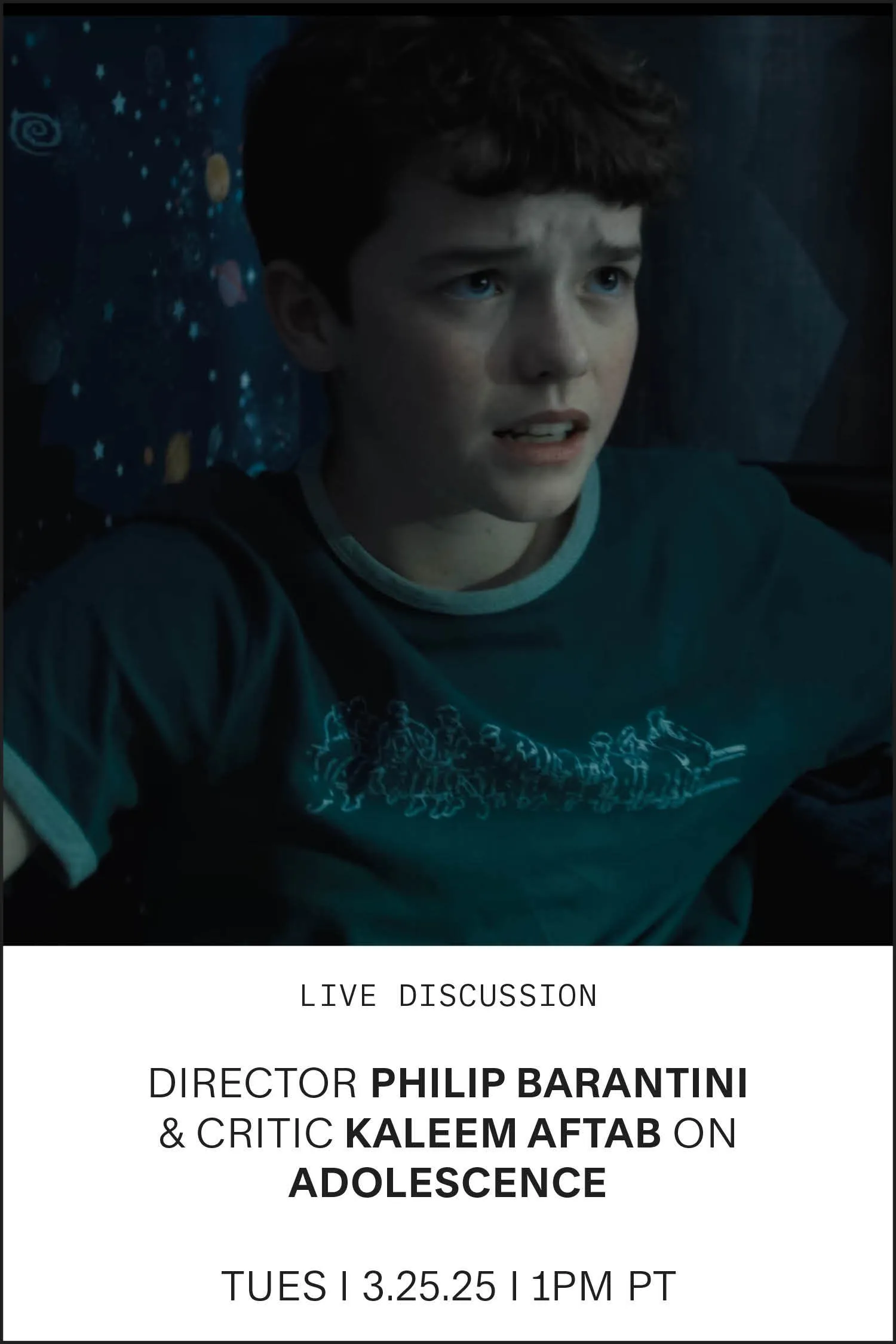

Adolescence, dir. Philip Barantini, 2025

Adolescence in One Take

Director Philip Barantini’s series is an unflinching look at youth incel culture. It’s also a technical masterpiece.

By Kaleem Aftab

March 28, 2025

A one-take film? We’ve seen it before: Russian Ark (2002), Victoria (2015), 1917 (2019). But a whole TV series? At the pace Adolescence moves? That’s something else entirely.

A deep dive into incel culture, masculinity and the harsh realities of teenage life, Adolescence is a gripping drama about a 13-year-old boy (newcomer Owen Cooper) accused of killing a classmate, and the crime’s impact on his family and community. The four-part Netflix series stars a gritty Stephen Graham as a father coming to grips with the violence of his “normal” son and where things went wrong. Beyond the storytelling, it’s also a radical technical experiment that director Philip Barantini pulls off brilliantly. Shot entirely in real time, each of the four episodes is told in a single shot. Barantini, who has also worked as an actor (Band of Brothers, Chernobyl), throws you smack into the crisis with some of the most jaw-dropping camera moves ever seen on television. The aesthetic choice is all down to the director’s fearless approach: one take, no cuts, pure immersion.

Barantini is no stranger to this kind of high-wire filmmaking—his restaurant drama Boiling Point (2021) was a master class in real-time tension, drawing upon his own experiences working as a head chef. But Adolescence takes things to another level. It’s more expansive, more ambitious, more emotional: camera operators sprinting through the streets, seamless handoffs, deft use of drones and Steadicams, actors staying in character for an entire hour. There’s no room for error.

So how do you even begin to plan something like this? How do you make sure the audience is hooked on the story, not just the technique? And what happens if someone forgets a line 50 minutes in? Barantini breaks it all down.

From left: Owen Cooper and Erin Doherty in Adolescence; Stephen Graham and Owen Cooper in Adolescence

What was the genesis of Adolescence? How did you land on such a culturally pressing topic of incels and cyberbullying?

It all started with a Zoom from [production company] Plan B asking me if I’d be interested in doing a TV series in one take with Stephen Graham. They said, “Go away and come up with an idea!” I knew nothing about incel culture really, but we soon realized that this is such a huge deal, and we really wanted to explore the “why” and try to understand it. As a parent it really struck a chord.

A one-take film. How would you describe this?

It puts the audience in real time, with a real-time perspective and a real-time view. It does two things for me. One, for the actors it’s live, so they have to be in the moment. They have to really react to everything around them, and if something changes or something’s thrown at them, they have to be completely reactive to that. But the other thing it does is force the audience to really pay attention. It puts them in a situation where they can’t escape what’s happening. A lot of the time we watch something with one eye on the screen and one eye on our other screens. I love documentaries, especially ones like 24 Hours in Police Custody, where there’s a ticking clock and you’re driving toward an outcome. That was kind of the idea for Adolescence.

The one-take approach does all of those things—it puts the audience in a first-person view and makes them feel like they can’t escape. It’s not appropriate for everything. I don’t think it’s something I’ll do for every project—certainly not the one I’m doing now [Enola Holmes 3]. But there are moments where you can utilize that technique and it really works. For me personally, though, it’s always got to be a secondary thought. It can’t be the focus. If the audience is just watching the one take, then we’re not doing it for the right reasons. Hopefully, after five or ten minutes, they forget it’s a one-take and just get engrossed in the story, the characters and what’s happening in front of them live.

You spoke about putting the emphasis on the actors. Do you think having an acting background influenced your decision to film in this style? Or did you watch other films that used it?

It was a mixture of both, in all honesty. Victoria was one of the first ones I watched, and then I went and watched Russian Ark, Utoya: July 22 (2018), and all those incredible one-take movies. But yes, certainly, as an actor, putting the actors in the zone and having them stay there for an hour—or however long it is—that’s when magic things can happen. I’ve been on so many sets as an actor where you come in, do your scene and then go again, and it’s great. But I think any actor who loves the craft knows that a lot of actors also do theater, and this feels like theater. But instead of the actors coming on and off the stage, the actors stay where they are, and the camera is the eyes of the audience—it moves to them. I always tell them, “Don’t break character,” because you just don’t know what’s going to happen—especially when you’re working with someone like Stephen Graham, who is such an instinctive actor. He’s just in it, and it’s such a joy to watch him work. It’s the same for everyone else around him.

What do you look for in an actor when executing a one-take production?

The casting process was really important—it always is, but especially in a one-take. You need actors who can react in the moment and who aren’t going to crumble or think, Oh no, I forgot my line, I didn’t say that line, so everything’s messed up. You just go with it and see what happens. Instead of putting the attention on yourself and thinking about what you’re going to do next, just put your attention on everything around you—just listen and be in that moment.

That’s how we act in life—you don’t know what’s going to happen at any given moment. That was kind of the influence for me. As an actor, I was instinctive—I fed off things around me. But when you’re on set and the crew is messing about, and then you suddenly have to do a take, then turn the cameras around and do it again, it becomes mechanical. It doesn’t feel like you’re in it.

So how does it change for the actor when they know they have a cameraman observing them for an hour and they cannot break character when the camera is pointed at them?

Having the actors just play for an hour—obviously, there’s a camera, there are a couple of boom ops, but the rest of it is hidden away. The actors are the only people they can really see. I spoke to a few of them, and after five minutes they forgot the camera was even there. That’s what you want.

I love working that way. But at the same time, I don’t want to be known as the guy who just does one-takes. The project has to fit that mold; otherwise it doesn’t work. You’ve only got an hour through each episode of Adolescence, an hour and a half for Boiling Point, and you have to fit a full, rounded story into a real-time hour. You can’t cut to two days later or flash back. It’s tricky—it’s stressful—but I thrive off it.

So much casting today is done with self-tapes. But I imagine you can’t cast off a self-tape for this. Is there anything different you do in the casting process?

Yeah, it’s really meticulous—the way I cast in general, but especially for this. It usually starts with a self-tape, actually. For example, with the Jamie character, I wanted a real 13-year-old boy, because that’s who the character is. You get all the nuances that come with that. We searched high and low for this character. I always send them either a video of me explaining what I want in the scene or a voice note, because you don’t generally get that with self-tapes. Usually, you just get a breakdown: This is what they want you to do, off you go. I want to give them as much opportunity as possible to do it well. I was blown away by Owen because of his naturalism.

One of the first things I asked the boys to do was to imagine a scenario where you’re at school and you’re being pulled into the teacher’s office. In one scenario, you’re guilty of whatever they’re blaming you for, and in the other scenario you’re not. The reason for doing those two scenarios is that I didn’t want them to be different. If you’re guilty, you’re trying to hide it. If you can hide it well, then you don’t come across as guilty. If you’re innocent, you don’t need to hide anything. So there are slight differences, but I didn’t want the guilty version to be, “Oh, I’m really guilty of this crime!”—you know what I mean? Finding actors who could play on those nuances without feeling over the top was key. Then we got them in to read some stuff, and I threw little spanners into the works. I’d have them react naturally to something they weren’t expecting. I didn’t tell them I was going to do that. I was just testing them all the way through.

It’s also important that they understand they have to be in character for an hour. Some actors are terrified of that and some thrive on it. It’s really meticulous the way we find these actors. They have to understand that they can mess up their lines, they can stutter, they can be real and normal—because that’s what life is. Life isn’t perfect. I didn’t want these characters to be perfect. Once they understand that and embrace it, it can be a beautiful thing to watch.

“You need actors who

can react in the moment

and who aren’t going to crumble.”

What was the experience like working with such young actors, especially given this intense subject matter?

Working with young actors can be tricky, so it’s important that they always feel safe in the environment, which is why we had child psychologists on-site the whole time. This enables the actors to be able to do the best work they can. We worked very hard to make sure everyone was comfortable with one another, so that they were able to really play. All the kids became very close, and they have about seven different WhatsApp groups between them. I’m like a proud father!

Did you shoot the series in episode order?

No, we shot in this order: three, one, two, four.

That’s insane. Was episode three Owen’s first-ever shoot day?

It certainly was! And it scared the hell out of me, but he smashed it!

In terms of coordinating with cinematographers, we talked about the story always coming first and then deciding on where to shoot afterward. Boiling Point is set in a single kitchen location, but Adolescence takes it even further. I’ve never seen anything done in one take at that pace. Can you talk a bit about the planning process and who that involves?

It literally involves absolutely everybody. We always knew we were going to do this in one take, so when Jack Thorne was writing the script we had that in mind. The difference between Boiling Point and Adolescence was that with Boiling Point we had the location locked in before writing the script, so we wrote it around that space. With Adolescence we wrote the script first, then had to find locations that were within the right vicinity to allow the car to move from one position to another. That was logistically challenging. But it was crucial to bring in every department much earlier than usual, because everyone’s voice matters. If, for example, we want to shoot a certain way, but the location doesn’t match or there’s some other constraint, it’s better to have everyone in the loop from the start rather than explain everything 15 times.

My cinematographer, Matt Lewis, who I’ve worked with on everything, has an incredible shorthand with me. He’s also the camera operator. But early on, we realized he wouldn’t be able to sustain holding that camera for the entire shoot—especially with the pace we were working at. What we were attempting was virtually impossible for one person, so we decided to bring in a second camera operator. They would pass the camera between each other as we moved through the shoot. The choreography of that was meticulously planned. For example, in episode one, when we go into the van with DI Luke Bascombe [Ashley Walters], Jamie Miller [Owen Cooper] is already inside. What you don’t see is the second camera operator sitting in the van, ready to receive the camera from Matt. He holds onto it as they drive to the police station. Meanwhile, Matt is in another car, driving ahead of them, so that when [second camera operator] Lee David Brown exits the van, he can pass the camera back to Matt, who follows him into the station. At the same time, Lee runs around the back of the station, ready to take the camera again.

It’s a constant back-and-forth, all choreographed down to the finest detail. We shot a lot of behind-the-scenes footage, which should be released alongside the series to show people how we did it. It was such a massive undertaking, and having everyone involved from the very start was critical. If even one person was behind on the process, it could slow everything down.

Boiling Point, dir. Philip Barantini, 2021

“One of our rules is that the

camera must always follow someone.

it can’t just wander off unless it’s motivated.”

Can you talk about the technology? How do you choose the cameras? How do you decide who operates what?

The camera choice was an interesting one. When we shot Boiling Point, we used the Sony Venice. Since it was all in one location, Matt had it mounted on an Easyrig, which attached to a line with the camera body on his back. It was incredibly heavy and he couldn’t take it off. But once we realized we needed to pass the camera between operators [for Adolescence], we started looking at lighter options. We considered a few Sony models before stumbling upon the DJI Ronin 4D. It’s not typically used in high-end TV or film—it’s more common for music videos and smaller shoots—but it has the same image quality as the bigger cameras. Most importantly, it has a built-in gimbal [a motorized camera-stabilization device] since it’s made by Ronin, which specializes in gimbals. That was a game changer, because it allowed us to switch seamlessly from an almost Steadicam-like shot to rough, handheld movement. That transition had never really been done before, and it excited us. The next step was getting Netflix on board, since they had never used this camera before. We had to ensure it met all their technical requirements. Once we got the green light, we were learning as we went. None of our team had used this camera before. But by the end of it, they were experts. In fact, Matt Lewis was so impressed that he just bought one last week—he’s obsessed with it now.

The camera’s lightweight design made us incredibly nimble. We could attach it to a drone, then detach and walk with it, passing it through windows, through cars, mounting it on the front of a van and driving away. Once we found this camera, we were off to the races—it felt like it was made for what we wanted to achieve. Of course, there were still nerves. No one had ever recorded with this camera continuously for an hour before. Extensive testing was done, but there was always that lingering question: What if today is the day the camera fails? But you know what? It never did. It’s an amazing piece of kit.

How many run-throughs did you do without actors—just with cars, vehicles and locations?

We did a bunch of tests. Matt and I, along with some key crew members, would rehearse moments like passing the camera into the van or attaching it to a vehicle. The drone stuff, however, was a last-minute addition, so we didn’t get much rehearsal time for that.

Before any actors stepped on set, Matt and I ran through the camera moves extensively. It was important to establish the baseline movement before introducing actors, so we could guide them into position rather than disrupting their performance. That said, we were always open to changes. If an actor felt a movement didn’t work naturally, we’d adapt. Each episode had a three-week block. The first week was just camera and actors, blocking every moment. The second week was a full tech rehearsal with every crew member—costume, makeup, everyone. We ran it every day, tweaking as needed.

For the actual shoot, we worked in a structured way. By 10am, everyone was on set, in costume and makeup. We’d shoot for an hour straight, then cut. After a three-hour break for lunch and notes, we’d shoot again in the afternoon. By 4 or 5pm, we were done. It was an incredibly efficient way to work, but the meticulous planning was crucial.

You mentioned the drone—let’s talk about that.

Originally, in an early draft, Jack had written a moment where the camera just floated off on its own, following an older lady down the street before returning to the school. But one of our rules is that the camera must always follow someone—it can’t just wander off unless it’s motivated. That scene didn’t make sense to Matt and me. Then one day in the office, I asked Matt, “Has a camera ever been connected to a drone and just flown off?” He wasn’t sure, but he’d seen videos of drones landing and then being disconnected. So we came up with the idea: What if we do that?

At first, we planned to have the camera fly over the site where Katie had been killed and then just keep going. But then, Toby Bentley from Netflix suggested landing the camera again. He pitched the idea of it touching down where Stephen Graham is laying flowers. He asked, “Do you think we could pull that off?”

At that point, it was already Tuesday of the shoot week, but I was like, we have to try. The next day we came in early to rehearse. It was tricky—the wind was brutal, and Matt was stressing because we hadn’t completed the episode yet. But on the very last take of the last day, it landed perfectly. That’s the take we used. When it happened, we were behind the monitors, waiting for 20 minutes with no connection. We had no idea if it had worked. When we finally got the call that it landed, we went wild. It was like winning the World Cup.

Stephen Graham and Philip Barantini on the set of Boiling Point

From speaking to you before, I know you’re a purist. You insist that a one-shot film is a one-shot film—you don’t like films that do little cheats. Can you talk about this purism and the challenges that come with it?

Yeah, yeah. I mean, if you’re going to say you’re doing a one-take film, then just do it. There are ways of doing it. I think it’s nerve-racking for producers, and it was certainly nerve-racking for everybody involved, but I knew it could be done. Matt Lewis knew it could be done. Stephen Graham obviously knew it too, having been in Boiling Point.

I think what it does is put you in a real-time moment for one hour. You want to be immersed for that hour. I mean, entertaining is probably the wrong word for this project, but it makes you pay attention. It makes you think. Hopefully, it’ll be a talking point. But more than anything, it creates that extra layer of tension. If you’re doing a true one-take, hopefully people aren’t sitting there looking for cuts—because there aren’t any. It would make my life much easier if there were, and everyone else’s too! But there’s something about it that really sparks a kind of magic with the actors and the crew. And I feel like we’ve made something really special with this one.

You put so much emphasis on the story, making sure the camera moves in a way that doesn’t draw attention to itself. What, for you, prevents it from being just a trick?

It’s the way the camera moves. You don’t let it be too stylized or too clever—it’s just got to flow naturally. If the camera instinctively moves toward something, rather than forcing the audience to look somewhere, then it feels like they’re in control. It becomes more immersive.

Once you get that down, and the audience is completely zoned in, then it stops being a gimmick. Obviously, we do some crazy things in this, but hopefully it never feels like a gimmick.

It has to be a subconscious thing—an extra layer of tension. I don’t want the audience sitting there thinking about the fact that they’re watching a one-take. I want them to just get lost in the story, the characters, and the performances. Then maybe on the second watch, they go, “Hang on a minute—the camera’s still going? There’s no cut?” That’s the goal.

The show spotlights the dangers of social media for kids—teens especially—addressed by Jonathan Haidt’s best-selling book The Anxious Generation. How do you hope the show might affect government regulations around kids, phones and social media?

We hoped to spark a conversation, and I feel like we have definitely achieved that. I think we should be worried about incel culture, and the government, parents, schools, etcetera, should be keeping a close eye on it. I hope this might be the beginning of something, for sure.