Ali Abbasi's Radical Empathy

By Kaleem Aftab

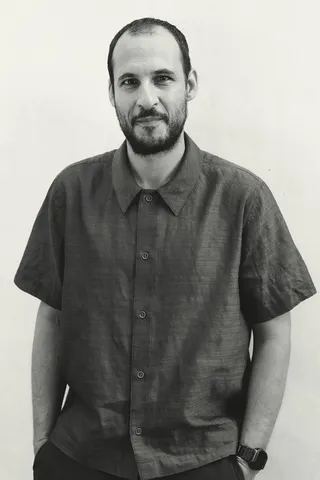

Ali Abbasi (photo: Bailey Beckstead)

Ali Abbasi’s Radical Empathy

kaleem aftab

The director of the Trump creation myth The Apprentice contends with monsters and metamorphosis

October 18, 2024

Ali Abbasi is not the first man born in Tehran to have annoyed Donald Trump, but he’s surely the first to do it through the art of cinema. Writing on Truth Social, President Trump called The Apprentice “A FAKE and CLASSLESS Movie [which] will hopefully ‘bomb,’” decrying its depiction of his relationship with Ivana Trump. The film imagines how Trump (Sebastian Stan) was given lessons in life and leadership by his mentor Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong), as well as the destructive beginnings of the young scion’s relationship with Ivana Trump (Maria Bakalova)—including an alleged sexual assault, first mentioned in a court case in 1990 and which Ivana later retracted. Of course, further winding Trump up, the film lands just as the 2024 Presidential election campaign enters its final lap, in a race too close to predict.

But despite the MAGA leader’s rage against the movie, The Apprentice offers a somewhat sympathetic portrayal of the 45th president in the years before he became a household name through his business empire and public persona. That should come as no surprise, given that Abbasi has excelled at operating in the gray area through films such as Danish horror drama Shelley (2016), Swedish fantasy trip Border (2018) and Iran-set serial-killer thriller Holy Spider (2022). In less than a decade he has established himself as one of the most exciting and emotionally nuanced filmmakers working today.

From left: Jeremy Strong as Roy Cohn, Sebastian Stan as Donald Trump and Maria Bakalova as Ivana Trump in The Apprentice

In Shelley, an upper-middle-class woman desperate for a baby turns into a murderer. In Border, airport security guards become trolls. In Holy Spider, an investigative journalist goes from pursuer to victim. And now with The Apprentice, a brow-beaten man turns into a hypermasculine monster. These are all films about ordinary people who become extraordinary. What is it about the moment of transformation that intrigues you?

It’s the act of transformation itself. For me, transformation is the core of drama. It’s not about transforming from one thing and then becoming another and showing what happens. It’s about the process, because that is where you learn so much about the character and human beings. Comparing the before and the after is a cathartic experience, so I like characters who have extreme transformation, and in a funny way that puts me in the same box as superhero movies. I would say that in a typical Spider-Man movie, the first 10 or 20 minutes is about the transformation and the rest of the movie is about what Spider-Man can do. Whereas my Trump movie is 98 percent transformation and the last two minutes show what he is capable of doing. When I was talking to Sebastian Stan about Trump, I argued that what is really intriguing with Trump’s story is that it could happen in India or Japan—anywhere where you are the heir to a family business, you have your dad’s expectations and you want to do something else. You’ve seen it, from Shakespeare to The Godfather to reality TV.

Are you interested in transformations because you were born and grew up in Tehran, then emigrated to Sweden to study architecture and finally landed in Copenhagen after enrolling at the National Film School of Denmark?

I think people would expect me, because I’m brown and from the Middle East, to make certain kinds of movies and certain types of art. The funny thing for me is that when people talk about a personal approach to filmmaking, or a personal style, I’m like, Which one? I have stopped thinking of myself as an Iranian who went to Sweden and then Denmark. I have more of a floating character identity, which is not only a function of where I was born but where I live. It’s my socioeconomic background and the part of town I live in.

When you are making films like Shelley, which you cowrote with Maren Louise Käehne (The Bridge), could you bring any personal elements into the story of a couple desperate for a baby who employ their Romanian maid as a surrogate?

My artistic strategy is that I’m interested in the “other,” and that gives me a lot of latitude without necessarily having to pigeonhole myself. I’m interested in things that I don’t understand and being pregnant is one of them. I always felt that being pregnant is like a horror story. It’s like the movie Alien—something is growing inside of you, and you don’t even know what it is and then later it becomes a human.

Why does your interest in the “other” so often manifest as violence in your films, whether it’s murder in Shelley and Holy Spider or sexual assault in The Apprentice?

Well, as human beings we are in all sorts of power structures. As much as you want your relationships—personal, work, whatever—to be fair and balanced and non-hierarchical, all that crap, they are not. Actively or passively, you are in a power relationship. Power and violence are on the same spectrum; violence is sort of enacting power in a certain way. Violence doesn’t have to be rape and murder. It can be verbal. It can be in the energy. Eventually, when you see the world with a little bit of distance and coolness, you see those things. I don’t like violence. There is a scene in Holy Spider where they hang Saeed, and it was actually traumatic for me because I had to watch real footage from hangings in Iran, which is so barbaric. It doesn’t matter if it’s a Muslim country, a Christian country or godless. I wished I could take it out of the story, but that just didn’t seem truthful. I really don’t take pleasure in showing violence, and I don’t think others should take pleasure in it either. I don’t think that if you watch Holy Spider and he’s trying to kill and do whatever with women that you should sit back and go, Oh, that’s a pretty cool way of shooting it. Then I’m not doing my job. It’s a difficult dance to show that and not be gratuitous. Look, there is Quentin Tarantino and he loves that shit and that’s okay, I don’t think he needs to answer to anyone. But I just don’t have that same temperament.

Is that why you didn’t want to paint President Trump as just a bad guy, but also show that he’s a guy 50 percent of the electorate can vote for—that he’s a regular guy who can be influenced by others and his circumstances?

Politically, I have huge disagreements with him. But he is just another human being. It doesn’t even take courage to say that. And that obvious matter is buried under a ton of shit—he is partly responsible for inciting violence, inciting inflammatory speech himself, and this binary system where you have Team Blue and Team Red is strange. President Obama said it really well in that White House Correspondents’ [Dinner speech]: We have fish and we have steak tonight, and you might not like fish or meat, but those are your choices. I feel like that’s what people think in these elections: I’m vegetarian, but there is fish and there is steak. I think we are trying to give people a third choice—there is fish and steak and then there is salad. There is a complexity in this world that is often forgotten because it’s a pain in the ass. Not only a pain in the ass for people in power but also intellectually. People are like, Spare me this crap with humanity, just tell me: Is she going to win or not? My function is not to tell you what is black and what is white. My function is exactly the opposite.

Something fascinating about your films is their use of color. As soon as The Apprentice started I thought, Ah, this is mimicking the tones of ’70s cop movies. When I watch Holy Spider, it’s more like a noir film than the usual Iranian palette. In Border, the colors switch from the cold tone of the security gates to the warm palette that takes over when they turn into trolls. A similar morphing of colors happens in Shelley after the baby is born.

I’m sitting with all these dials in a grading room that I can adjust to get my expression across because there is not really a message. I love expressiveness; that is my temperament. I like vibrant experiences. I love to be overwhelmed when I go to the theater. The same with music. I also love the other end of the spectrum, which is minimalism and very clean and detached experiences. What I don’t love is the middle, rendering things the way they are. I then think, What is the point of me doing anything? There should be a point of view, there should be a temperament. With Holy Spider, there is this notion that anything with the Middle East or East Asia has to be in warm green colors with this ethnic music playing and I was like, No, my experience of this city is a noir city. This is Chinatown. What I associate with noir is things popping out, contrast and life. If you ever go to Mashhad, there is all this neon and part of it looks like Hong Kong. A religious place is not supposed to look that way, but it does.

Ali Abbasi (photos: Bailey Beckstead)

“I’m interested in things that I don’t understand and being pregnant is one of them.”

When you approach each movie do you have a process or does it change each time? Are you selecting actors the same way?

It changes, because there’s a difference between going through the whole Hollywood mill and going and talking to people I know relatively well, or maybe even intimately well, who live two streets from me. But I think what remains the same: 80 percent of my job is casting. I have no illusions about myself as a filmmaker. I’m not a very technically strong filmmaker in terms of working with actors. I don’t have this Ali Abbasi method in the way Mike Leigh has his. What I do know is that the way I work with actors puts a lot of responsibility and freedom on their shoulders, which means that choosing the right person is integral. Therefore, I spend a lot of time—often years—finding people. I have many conversations and I try to get to know people as much as I can. I don’t think that changes, honestly. But obviously, there are practical implications of working in the Hollywood system. For example, I am not used to a system where people think auditioning is beneath them or offensive. I found that really strange, because an audition is a two-way street. I’m auditioning you, but you are also auditioning me. That’s also your chance, because you want to spend a month, months or even years working with me, and I know that my way of working is not standardized, so this is our chance to actually see if it can work, instead of us trying to figure it out on the first day of production. I think that’s not wise.

How was it on The Apprentice? Did you meet Sebastian, Jeremy and Maria before?

Without going into too much detail, some things I got to know through auditions, some through conversation. It’s almost like a relationship. When casting, you meet a lot of people, but then you end up being together with someone and only afterward can it be rationalized—why that guy? Oh, because he was tall and he had a beautiful smile. But that’s sort of like when you try to put words on your dreams. There’s a lot of gut feeling and intuition, and then there are also obviously certain technical things. I love casting. It’s almost unreal that this is part of my work. I’m getting paid—or not usually getting paid—to talk to people and assess them. And for what? For something very subjective.

Do you see your role as almost a psychologist?

Well, no. I’d see myself as a sort of a captain of a pirate ship that has docked, and I’m down in the harbor’s brothel, trying to see who’s available and, like, one guy’s high, one guy is fucking someone, one guy is drunk, and I’m like, “Hey, it’s going to be great. Come to the ship. It’s going to be smooth sailing, we are just going to pull over the Atlantic and we are done. I want to make the Atlantic great again.”

![]()

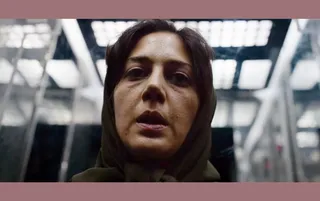

Holy Spider, dir. Ali Abbasi, 2022

![]()

Border, dir. Ali Abbasi, 2018

Another thing that is striking about The Apprentice is the view of masculinity you bring to it. Masculinity is shown to be something that can create difficulties, but it’s also alluring and powerful when a guy portrays himself as knowing what the world’s about.

Things have really changed on that account since the 1970s, but in a way, there’s always this very alluring simplicity: “Be a man.” But what does that really mean? I wish I knew. I do know, for some people, that’s something really concrete. When people talk about the rape scene with Ivana, you can talk about it as a rape scene, but in fact, seen historically, it’s not a rape scene, because I’m sure in the ’70s and ’80s, and probably up to ’90s, a lot of men made their partner have sex with them, and socially it was accepted, tolerated, whatever you would call it. You might have felt violated emotionally but you didn’t think, Okay, this is like rape material. It’s important to think about that, and why I think it’s important to see Ivana that is with him after that scene, because that’s also what happened.

We try not to lose our moral compass, but we’re depicting these things as experienced by Donald with Roy Cohn at the time. I put the minimum screen time possible of what I think people should sit through to understand and experience what happened [and how they acted]. If we wanted to be more gratuitous, we could go many places and this generally holds for the whole movie, I would say, because if there’s a person who gives you enough ammunition for a complete character assassination, it is this guy.

The mixed reaction to The Apprentice made me think of Scarface. Like, many critics hated it, but when it came out the public identified with Tony Montana.

I love Scarface, it’s a very operatic movie somewhat like Casino is also, for me. Apropos the whole conversation about complexity versus simplicity—people are just too afraid to make those decisions now. By coming out against the film, Donald Trump has helped us by making that choice, giving us that context. And my prediction is now it’s going to go well for the movie suddenly, because it’s like, “Okay great, he hates it, now we can go and watch that movie.” It’s the same fucking movie, and I don’t care if he hates it or he loves it.

What made you want to be a filmmaker? Why is cinema your medium and not singing songs or writing books?

The easy answer is that I tried the other things and I failed, including architecture. I remember I read about the great Iranian filmmaker Sohrab Shahid Saless. He wanted to study at a film school in Vienna and in the admissions interview he said to the professor, “You have to have me” and the guy said, “Why?” He replied, “Because I have cinema in my blood,” and the professor says, “Well, let’s then go change your blood.” I don’t know if I have cinema in my blood, but I think I am a good combination of a circus director, a dictator and a humanist. I think that sort of split personality is helpful in cinema, because it’s such a bizarre job. It’s like being an army general and the medic at the same time, writing about the atrocities of war. I started writing. I published some short stories in Iran and I always thought it was tough to write, because I could do anything. I can write at any length. Nobody would stop me if I wrote 10 pages, saying, “This is too long.” I like that there are clear limitations when it comes to the film world. But I guess part of why I’m doing what I’m doing is I’m trying to figure out why, honestly. Maybe when I find out I will stop and go farm or something.