Blood, Sweat & Tears

By Adam Nayman

The Thing, dir. John Carpenter, 1982

Blood, Sweat & Tears

Made in the pre-CGI days, John Carpenter’s The Thing remains a triumph of analog horror

By Adam Nayman

October 13, 2023

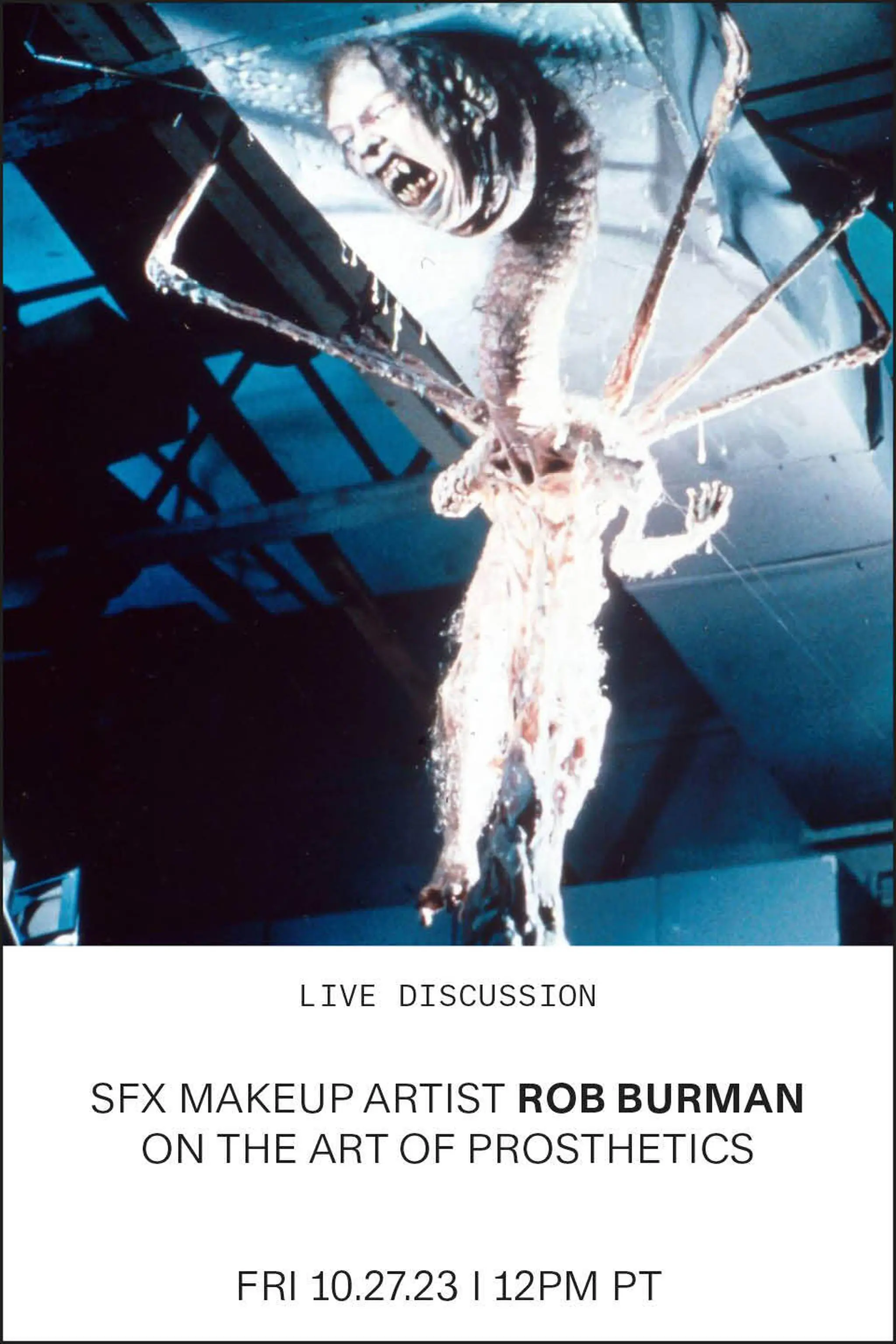

INT: U.S. OUTPOST 31, ANTARCTICA—NIGHT. With his compatriot lying prone and shaking on an operating table—symptoms of a possible heart attack, brought on by the stress of living in close proximity to a recently defrosted outer space monster—a physician acts swiftly and decisively to apply a defibrillator. On the second pass, the patient’s chest cavity collapses inward to reveal a toothy, gaping maw; the mouth quickly clamps down on the doctor’s arms, severing them neatly at the elbow and removing any ambiguity about the patient’s true condition. He was a Thing all along. Clear.

From left: T.K. Carter, Kurt Russell and Donald Moffat in The Thing, dir. John Carpenter, 1982; the Thing in The Thing, dir. John Carpenter, 1982

If cinematic gore has an apotheosis, the “chest-compression sequence” of The Thing (1982) is destined for divinity, though it has some competition from within its own film. Depending on your frame of reference, the film evokes either a Francis Bacon painting (think Figure with Meat) or a pulled-pork sandwich, with various flavors of flesh—human, canine and extra-terrestrial—sliding tenderly off the bone, sizzling on the snow, or getting roasted over an open flame. Circa 1982, many observers (and watchdogs) were of the opinion that its account of a scientific expedition infiltrated and decimated by a shape-shifting alien intelligence—a scenario adapted from John W. Campbell’s 1938 novella Who Goes There? by way of Christian Nyby and Howard Hawks’s 1951 film version, The Thing from Another World—was just about the squishiest, and maybe the sickest, movie ever green-lighted by a major Hollywood studio. Or as David Clennon, playing the ornery mechanic Palmer, so succinctly puts it at one point, “You’ve gotta be fucking kidding me.”

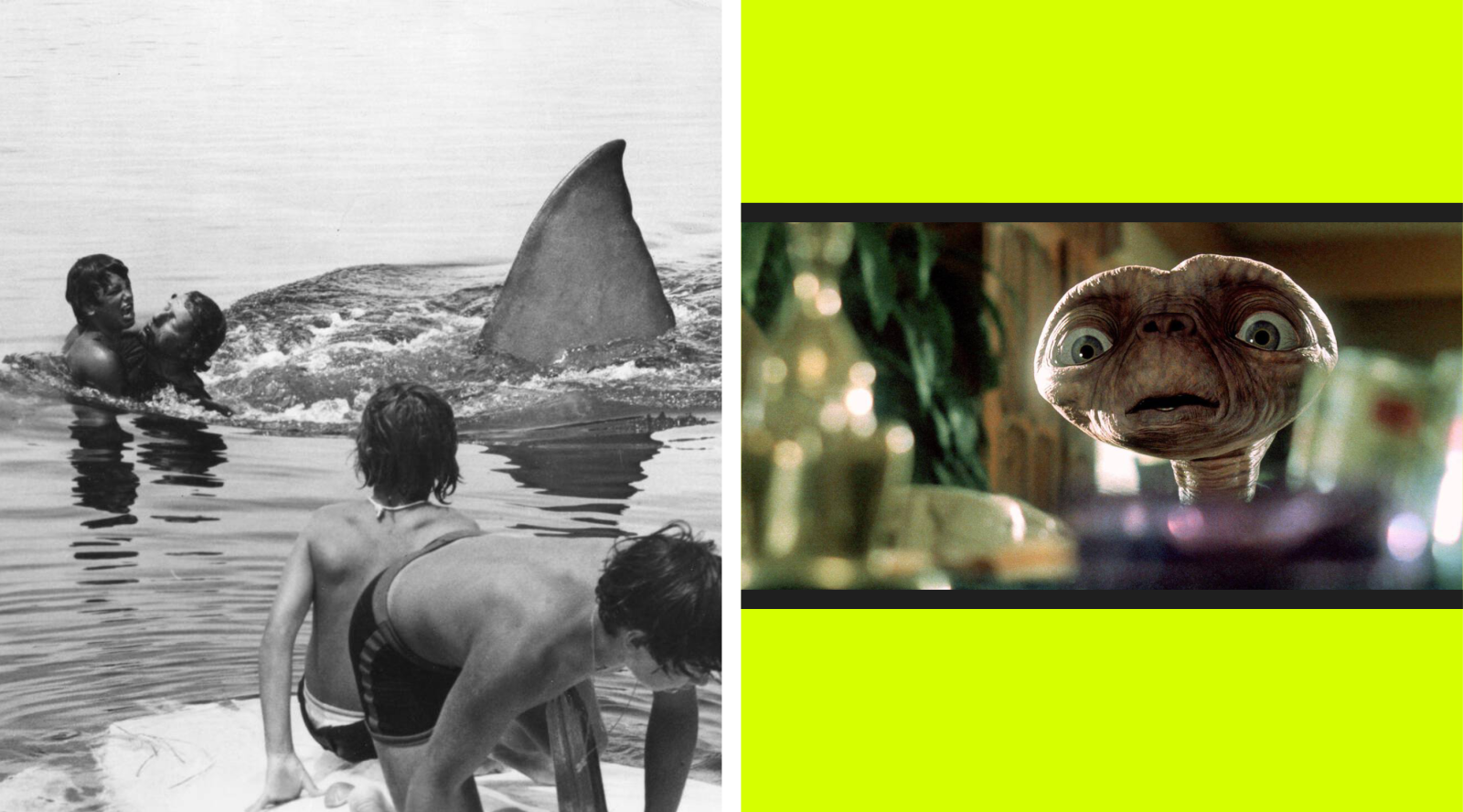

The hard-R granted to The Thing by the MPAA placed it staunchly at odds with that summer’s PG-rated Spielbergian zeitgeist. “We’re dead,” remarked producer David Foster after attending a sold-out screening of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, where the moody, ominous advance trailer for The Thing—whose lavish budget of $15 million dollars was 50 percent higher than that of Steven Spielberg’s crowd-pleaser—was received in “icy silence” by the audience of “grandmothers escorting their grandchildren.” As visions of close encounters indebted to the comic-book iconography of the 1950s, E.T. and The Thing were at once equally well engineered and tonally antipodal. Where Spielberg’s fable gently tugged at the heartstrings, Carpenter sought to rip them out, along with all the other major organs.

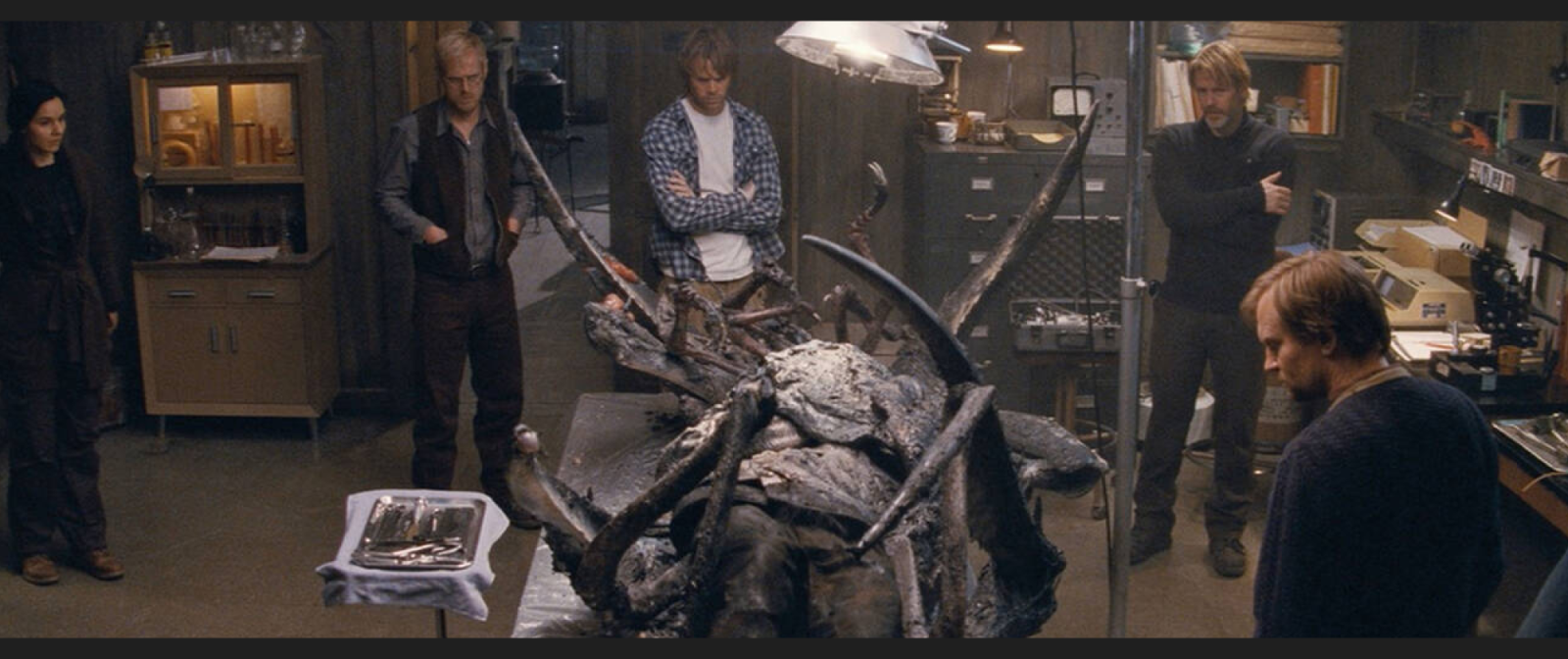

The Thing, dir. Matthijs van Heijningen Jr., 2011

Considering that Carpenter had made his name with the proto-slasher Halloween (1978), The Thing’s violence wasn’t exactly a surprise, but the sheer ferocity of the bloodletting, combined with the obliterating bleakness of the narrative, left a pungent residue: Viewers were left splattered in bad vibes. There was something almost polemical about The Thing’s reception, as if the trip wire around an invisible mainstream boundary line had been transgressed. Finally, a filmmaker working under the sign of Star Wars (1977) and its bulbous latex creations had gone too far. In Newsweek, film critic David Ansen slammed Carpenter and his collaborators in the makeup and special-effects department for “sacrificing everything at the altar of gore.”

The high priest in Ansen’s analogy would have been the prodigious young makeup wizard Rob Bottin, who was all of 22 years old when he was tapped to supervise the creation of the film’s title character, whose representation posed a host of technical challenges wrapped up inside a larger and considerably more metaphysical contradiction. On one level, Campbell’s original story was a fable of horror hiding in plain sight, staring out from behind human eyes. At the same time, Carpenter was determined to actually visualize the “Thing” itself, and to hew as closely possible to the Lovecraftian prose and spirit of a tale inspired by H.P.’s frigid At the Mountains of Madness. Subtlety and shock were the twin poles of The Thing’s sensory assault. For every sequence of insidious, slow-burning suspense, there would be some kind of direct confrontation with, and contemplation of, viciously transfigured viscera: creeping dread leveraged against active disgust. “Look, this is the chance of a lifetime,” Bottin told Carpenter early in production. “It doesn’t have to look like one Thing. It changes constantly, so we can go wild with it.”

“The oozing, sinewy texture of the animatronics hinted at all the other fluids—blood, sweat and tears—that went into their making.”

Nowhere is this swaggering brio more apparent than in an early passage featuring the repulsive hybrid organism colloquially known as the Dog-Thing, which explodes out of the body of a wolf–Alaskan malamute unwisely taken into captivity by the all-American crew of Outpost 31. To return once more to the Spielberg-Carpenter dialectic, it was considered an act of almost sadistic ruthlessness when the former killed a dog—offscreen—in Jaws (1975). Carpenter ups the ante by forcing us to watch the good boy in question (played by a half-wolf canine actor named Jed) suffer terribly as its head splits open into a snarling, tripartite arrangement—a gooey Cerberus sprouting appendages in every direction and forcibly integrating the other huskies into its body. After being discovered by the station’s dog-handler, the Dog-Thing subdivides into a skittering insectoid critter and a “Flesh Flower” whose petals are made up of inlaid canine tongues and teeth. Bottin later said that the second effect evoked nothing so much as a “pissed-off cabbage,” and if one movie’s shadow falls over his work in The Thing, it’s Philip Kaufman’s brilliant, pod-infested 1978 version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which had also featured plenty of snaky, distended tendrils and a disturbingly mutated dog.

From left: Jaws, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975; E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1982

From watching the various making-of documentaries and behind-the-scenes featurettes that have been commissioned over the years for The Thing’s home-video and DVD releases, it’s clear that its money shots were highly physical propositions. The oozing, sinewy texture of the animatronics hinted at all the other fluids—blood, sweat and tears—that went into their making. The film’s makeup and prop departments buckled under the sheer weight of the raw materials needed to do the job: acrylics, gelatins, fiberglass. One iteration of the Thing was essentially a remote-controlled car with legs, dressed up to look like a mobile severed head; another took 300 pounds of rubber pressurized by hydraulic pulleys and a bathtub’s worth of fake blood. It took some 40 artists, technicians and puppeteers to pull the film off; by the end of the production, Bottin, who was working 18-hour days, seven days a week, was hospitalized for exhaustion.

The Thing is a resolutely unsentimental movie, offering up its interchangeably rugged characters as grist for the mill, or sacrifices at the altar of gore. Where Invasion of the Body Snatchers had lined up a cast of humane eccentrics, The Thing’s grunts are almost strategically indistinct from one another, especially when clad en masse in bulky, fur-lined parkas. Instead of making us truly fear for their individual identities, Carpenter uses his cast members as graphic elements in a tour de force directorial performance that revitalizes widescreen photography—the cliched compendium of vistas, valleys and horizon lines—by using it mostly to evoke interior claustrophobia. If we inevitably gravitate toward top-billed Kurt Russell as the resourceful helicopter pilot MacReady, it’s more a matter of the actor’s natural charisma than any detailed character work; MacReady is as much of a cipher as the others—a quality that helps to put over the enigma of the movie’s eerie, frostbitten coda, which finds Carpenter holding his cards so close to his chest that he risks having them gobbled up whole.

Where The Thing locates its humanity is, ironically, in its daunting, omnipresent array of hardwired (and hard-won) illusions. The pitched struggle between a team of skilled, stressed professionals and an entity that refuses to be wrangled has a documentary quality: Even as they offered up their own savage pleasures, Bottin & Co.’s cornucopia of old-school, practical tricks were also holding the line against a newcomer as malign, agile and all-devouring as the Thing itself. Three years before the first WrestleMania, the summer of 1982 staged a battle royale for the future of Hollywood special effects. In one corner, the tactile tag team of The Thing and E.T., whose star attractions seemed plausibly warm to the touch. In the other, the ephemeral sensations of Tron and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, which went where no blockbuster had gone before—across the uncanny valley, into the realm of CGI.

From left: Donald Sutherland and Brooke Adams in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, dir. Philip Kaufman, 1978

The Genesis device that eventually resurrected Mr. Spock doubled as the big bang for computer-generated special effects, prefiguring everything from Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and Jurassic Park (1993) to—wait for it—The Thing (2011), an affectionate but thoroughly superfluous prequel set directly before Carpenter’s classic. Probably the most interesting thing that could be said for Dutch director Matthijs van Heijningen Jr.’s feature is that it plays like a soulless allegory for its own source material—less as an act of entertainment than inhabitation, mimicking its predecessor’s textures so assiduously that even superfans would have trouble noticing the difference. The cognitive dissonance of watching 21st-century digital imagery designed to look like chunky early-80s gore was surpassed only by the feeling of how weightless the newer movie felt, how harmless and unremarkable and generic despite its array of allusions. Just over a decade later, The Thing 2.0 has been wiped from the collective pop-cultural consciousness, while Carpenter’s film remains the stuff that nightmares are made of—a movie to watch with a defibrillator in hand.

The Thing (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) by Ennio Morricone