Chloë Sevigny's Enduring Edge

By Christopher Bollen

Boys Don’t Cry, dir. Kimberly Peirce, 1999

Chloë Sevigny’s Enduring Edge

Christopher Bollen

The actor reflects on her complex character in the landmark film Boys Don’t Cry

June 3, 2024

In the 1990s the New York City film world felt very far away from Los Angeles. Back then the movie industries of NYC and L.A. could still be perceived as distant entities creating work for often vastly different audiences. This coastal cultural gap might be difficult to imagine from the vantage point of the all-consuming entertainment blender of the 21st century, but at the start of her career Chloë Sevigny seemed ours not theirs, a creature from the streets of downtown Manhattan (never mind that she grew up in Darien, Connecticut) and not a starlet conceived in the studios of Los Angeles.

Sevigny had been taking the train into Manhattan long before she was cast in her first feature film, playing Jennie in Larry Clark’s 1995 post-adolescent reality-shocker Kids. She went on to star in such independent fare as (her then boyfriend) Harmony Korine’s first directorial feature, Gummo, and Whit Stillman’s The Last Days of Disco.

Then an offer came along that appeared, at first, to be another New York City indie project but ended up altering the course of her career. That was Kimberly Peirce’s gut punch of a true story about the last days of Brandon Teena, a transgender man (played by Hilary Swank), who falls in love with a young woman (Sevigny as Lana Tisdel) in Humboldt, Nebraska, before being brutally raped and murdered. Boys Don’t Cry was a bellwether work, tackling trans life before the word even existed in mainstream vernacular. It proved to be not only one of the most important films of the 1990s, but it catapulted its stars—Swank and Sevigny—into the epicenter of Hollywood. Swank won Best Actress for her role as Brandon, while Sevigny was nominated for Best Supporting Actress. Watching the film 25 years later, it’s Sevigny’s performance, at once tough and sensitive, street-smart and wide-eyed, bound by her circumstances but capable of sharing Brandon’s wild hopes and dreams that, to my mind, serves as the film’s emotional key.

The rest is history—sort of. Sevigny has gone on to work on countless other projects on the big and small screens. Today she lives in downtown New York with her husband and four-year-old son. Galerie caught up with her to talk about Boys Don’t Cry and how the film did and did not change her life.

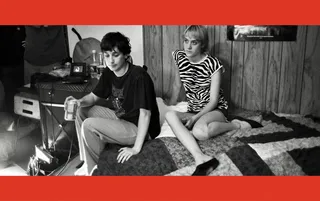

From left: Chloë Sevigny in Boys Don’t Cry and Kids

Let’s time-warp back to 1998, 1999 when Boys Don’t Cry was shot and released. Were you a tight-knit group of actors on set?

We were. Also, the producer was Christine Vachon at Killer Films and she’d also produced Kids. So I already had a real relationship with her. The casting directors, Billy Hopkins and Kerry Barden, were the hot New York casting directors. They cast everything. They had cast me in The Last Days of Disco. I was dating Harmony [Korine] at the time, and I remember Drew Barrymore had reached out to him about the story of Brandon Teena, because it had appeared in a magazine. She had sent him a printed copy of the article and these photos of her kind of in drag, you could say. Shot by Bruce Weber. She was like, “I want to play this part and I want you to direct it and I want Chloë to play Lana.”

So this had no connection to the Kimberly Peirce script?

This was totally separate. But Hollywood was interested in this story. People were talking about it. People were really struck by Brandon and saw the potential to make something powerful and moving in their story. I think Harmony maybe even met with Drew. I remember seeing her at a party in L.A. and us kissing in the bathroom and talking about it. Then fast-forward to Kimberly Peirce, who had a script, and Christine was producing. I went to audition for the part of Brandon.

How did you do as Brandon?

I thought I did a very good job.

Did you go in dressed as Brandon?

I was already into the androgynous thing, but more as a fashion sensibility rather than as a truly masculine point of view. If you recall, androgyny was chic and trendy in the ’90s. I was already inhabiting that with the short haircut.

Definitely your look in Kids was androgynous. Not so much The Last Days of Disco.

I had small boobs in Kids. It was before I blossomed into a woman. I was not fully formed yet. Anyway, I read some of the scenes. We probably had a long conversation, because Kim is very thorough. She asked me, “Have you ever wanted to be a boy? You’ve never wanted to be a boy, have you?” And I was like, “No.” I was always a girly girl. “You got me.” She said, “Well, come back next week and read for Lana.” So I went back in and read for Lana. Then I think they made an offer to Sarah Polley, and I was really heartbroken. I lost a lot of parts to Sarah Polley in the ’90s.

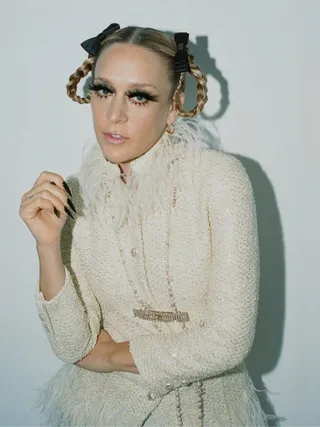

From left: Sevigny in Allure magazine, February 2023; attending a benefit in 2000; at the CFDA Fashion Awards in 2023

Really?

She got a lot of the cool movies that I wanted. We don’t have to go into the long list of them and dredge up some sadness. Now she’s a great filmmaker. But Sarah Polley passed on Lana, they came to me, and I was thrilled beyond belief. I went on a huge deep dive on the story, reading all the court transcripts, watching the documentaries. I still have those exposé shows on the case on a VHS tape at home. I just watched them over and over again. I fell in love with Brandon and this persona, this person who they were. Brandon was a total bad boy, which maybe the movie misses a little bit. If I have one critique of the movie—and this is not a critique of Hilary and the choices she made—I think it presents Brandon in more a classic cowboy trope. Whereas the real Brandon Teena had mad swag, like “Yo, baby. Yo.” Baggy pants, stealing cars, writing bad checks, a total bad boy, which is very sexy when you’re young.

Yeah, the Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry is much more sensitive and awkward.

I think Lana fell in love with this masculine character who she felt could protect her. That’s kind of the idea I was working with. I think I was even projecting Kim [Peirce]’s energy onto Hilary. Kim has kind of BDE energy, so I was kind of playing off that.

You never met the real Lana, right?

No, I think she wanted Julia Roberts to play her and I figured she’d only be disappointed that it was me. When I was nominated for the Oscar, it was so confusing for me because there was all the finery of the awards show, and to think of Lana back in her trailer in Kansas—I was feeling a lot of weird feelings and guilt around that, which I didn’t know how to process. Nobody really helped you with those feelings back then. Now I’m shooting this Menendez [Brothers] story, and the studio is like, “If you have trouble with the content in any way, here’s a number for a psychiatrist, and we will pay for your therapy if you were triggered or need help.” Back then there was no media training. There was no nothing as far as how we even dealt with such a sensitive subject, which is still such a hot-button issue. Even today there are people who think they should have cast a trans person as Brandon. I went on to play a butch lesbian in If These Walls Could Talk 2. And in my show Hit & Miss, I played a trans person. I don’t know how to apologize for all that now. At the time we thought we were doing the right thing.

It’s interesting you mention that. Those are valid conversations. But what struck me when rewatching Boys Don’t Cry was how much it stood the test of time. To me, it didn’t feel like a clumsy approach to representing trans lives. It’s been 25 years, but I was surprised by the sensitivity and care to the subject. We didn’t even have the word transgender in 1999. The idea of “trans rights” was so far from the public conversation.

I remember there were differences of opinion on set between Hilary and Kim on some of the choices on how to portray Brandon. I think particularly on the matter of the rape sequence. There’s a sequence right after it in a shed where she and I have this love scene. Hilary was adamantly against it. She felt that Brandon would not be, in that moment, open to that kind of thing. But Kim was like, “I really want this character to be able to be loved as she is.” So there was tension. But also there was a lot of sensitivity to all the choices that were made. Again, now there are intimacy coordinators on set, and you always can back out of something at any moment, even if you’ve read it and agreed to it beforehand. Everybody’s all for protecting the performers. At the time I felt like I was working for the director and it was her film. But looking back I feel like maybe I could have done more for Hilary in that moment.

From left: Gummo, dir. Harmony Korine, 1997; The Last Days of Disco, dir. Whit Stillman, 1998

Had you known Hilary Swank before you walked on set?

No. We had some rehearsals in the city. But she was married at the time and had a dog, and when she went down to Texas she stayed at a different hotel than everyone else. I think that was also a choice so she could feel more alienated from the group, which ended up kind of happening. The rest of the cast really formed a bond, and she was a little bit outside of that. We were hanging out and drinking every night, and she wasn’t interested in that. We were all young and hot and wanted to hang out. [Laughs] We were doing a film that was so heavy, we all wanted to unload at the end of the day and have a release. It did feel like a camaraderie between us. I remember Brendan Sexton throwing up on set after the rape scene. It was high stakes, high emotions. I was also kind of in love with Peter Sarsgaard.

Even beyond the heaviness of the film’s topic, you had to take a lot of risks in your scenes. Starting with singing karaoke in your first scene. That’s not easy, to walk up onstage and sing. And there’s obviously the orgasm scene.

Embarrassing. But yes, there was a lot of nudity and sexual situations. It was pretty intense.

Did you have any control over Lana’s style in that film? The red-blond of your hair is such an unusual shade.

Yeah, we were trying to match her hair color. And I remember we did my nail tips because Lana had long nails.

You have bright red nail polish on in the film. There’s a scene where you’re touching Brandon’s face with these red nails. It’s very seductive.

That’s what I wanted. I thought of them as kind of like Bonnie and Clyde. I wanted her to be sexy. I remember dyeing my hair in sinks on the fly. We didn’t even have trailers to change clothes in. It was very indie. Actually, I think we even ran out of money and IFC came in and helped finish production. We stayed in a Budget Inn or something in an industrial park. I don’t even remember what we ate or if we ate. I remember the rooms—they were on a parking lot overlooking a highway.

Was Kimberly very controlling on the lines and choreography of the performances, or was there room for freedom and improvisation?

There was a lot of freedom. There were a lot of conversations, a lot of rehearsing and blocking and feeling things out. She wanted to draw out a lot of personal things to pull out a performance. But Kim’s passion for Brandon was just contagious, as well as her respect for him and the story. I found it helpful. I mean, I’d only done a handful of films, so I was still pretty new in my career and I was just excited to experience different people’s styles. I’m more instinctual and less analytical, and Kim was very analytical. I was just like, “We can talk about it till the sun comes down, but let’s just do the scene.”

After you wrapped, did you have a sense that you had created an important film? It seems like a quick turnaround between filming and the release the following year.

Christine [Vachon] had such a good track record at that point. As a Killer Films movie, it was bound to do festivals. I was thinking, Oh, it’s going to do really well at Angelika [Film Center]. I had no idea that it would enter popular culture and be nominated for an Oscar. That was a big deal for a film of that size at the time.

![]()

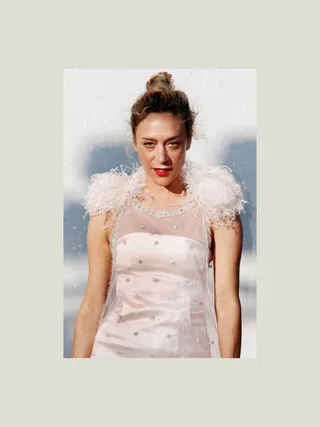

Sevigny at the Venice Film Festival, 2018

![]()

Sevigny with Bill Paxton in Big Love

“I thought of them as kind of like Bonnie and Clyde. I wanted her to be sexy. I remember dyeing my hair in sinks on the fly.”

It must have been so overwhelming for you, coming from indie New York films and suddenly being thrust into the dead center of Hollywood. You were nominated for Best Supporting Actress. Angelina Jolie ended up winning for Girl, Interrupted that year.

That was not a supporting part, by the way. She was the lead.

She was also an insider. A Hollywood baby.

We all knew she was going to win. It was a tough competition that year. The other actresses nominated were incredible: Toni Collette, Samantha Morton, Catherine Keener.

Wow, that was a good year. I have to say, it was wild to watch your ascent through Kids and Boys Don’t Cry in the 1990s. To those of us who were also young in New York at the time, I remember there was a lot of fascination around which way your career would go. I guess that’s because Hollywood seemed so far away from New York back then, and you were from downtown New York, from the home turf. That must have been a lot of pressure for you: Will you stay working in small art indies? Will you go full Hollywood and end up in studio films? Will you become a Gena Rowlands to Harmony’s Cassavetes? Did you feel an onus to stay in indie land, or were you thinking, I’m ready to do anything?

I did. Harmony and I felt so anti-establishment. We wanted to tear the system down. So ending up at the Oscars was pretty shocking. There was an idea after Boys Don’t Cry, “Oh, everything’s going to happen for Chloë.” But I’d already been pigeonholed in this indie world, and it was very hard for me to make the leap. There was so much about mathematics, how much money your movies had made at that point, even to get cast in indie pictures. So if you hadn’t been in any movies that had made any money, they wouldn’t cast you. Some people, like Michelle Williams and Kirsten Dunst, who’d been in Bring It On, which made a gazillion dollars, were able to bridge both words. I somehow missed that opportunity or wasn’t presented with those opportunities, so I feel like I kind of fell by the wayside. And I felt a little bit bitter about that.

So few actors have had the career longevity that you’ve had.

There were a lot of indies that I passed on that I wish I had done. There were a few small parts in bigger comedies that I now look back on and realize I could have done. But it’s always the what if. It’s a guessing game. You always think, Why didn’t this happen? Was I not pretty enough? Was I not a good enough actor? Was I not smart enough? Do people think of me only as a fashion person? Is it because I’m another blond white girl, and a blond white girl is the star and they surround her with brunettes.

Do you think you were perceived as too New York? Not enough L.A.?

I don’t know. Julien Donkey-Boy was doing the festivals at the same time Boys Don’t Cry was. What was my next role? I’ll have to look at my IMDb list. I did American Psycho after that. Then I did If These Walls Could Talk 2 because I had borrowed money from WME to pay my mother’s mortgage and they made me do that to pay them back. Then I did a short film with Jim Jarmusch in Ten Minutes Older. I did Demonlover, Party Monster, Dogville, Shattered Glass, Melinda and Melinda, Zodiac. I was always looking for stories that were challenging.

![]()

Harmony Korine and Chloë Sevigny, 1995

![]()

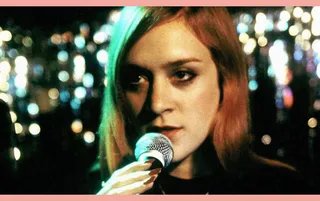

Chloë Sevigny in Boys Don’t Cry

You once told me that Lana was your favorite role that you’ve played. Is that still the case?

Outside of television, it’s the biggest part I’ve played. When Big Love happened, I was still plugging away in films, hoping to be some sort of character actress. I thought, I just want to have a home and a life and not have to be living check to check. Then Big Love was offered to me. I didn’t even have to audition. At the time, HBO had The Sopranos and Six Feet Under and I thought what was happening there was very exciting. But it was a real divide then between the film world and the TV world. You had to make a choice. I don’t want to sound like I’m apologizing for my career, or ungrateful or unhappy with how it’s been. But as far as the impact of Boys Don’t Cry on my career, that’s always been perplexing.

I was at a party with you a few years back when a younger actress thanked you for your role in Boys Don’t Cry. It’s arguably one of the most significant films about homophobia and transphobia ever made. I wonder if you get many responses from younger generations?

Yeah, I do. A lot of people still talk about that movie—that and Kids—and come up to me about it all the time. It’s still making an impact, and I’m endlessly proud of it.