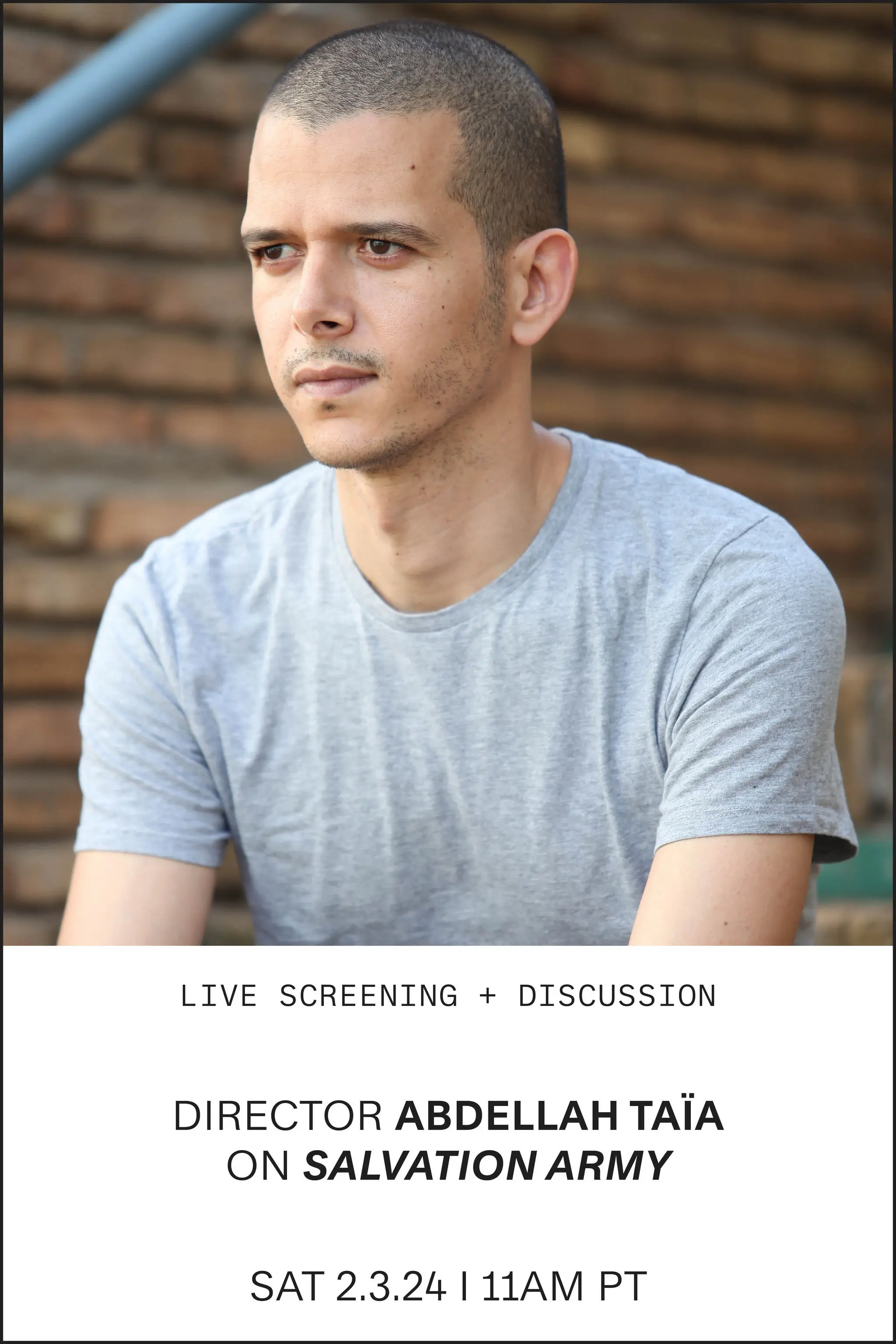

Cinematic Salvation

By Abdellah Taïa

Salvation Army, dir. Abdellah Taïa, 2013

Cinematic Salvation

When a Moroccan writer turned his debut novel into a feature, he discovered the freedom of—and angry resistance to—queer filmmaking

By Abdellah Taïa

October 2, 2023

It happened in Tangier a long time ago, back in the mid 1980s. But in my heart it took place last night. I remember everything—most of all, my absolute happiness.

I’m 12 years old. Maybe 13. It’s summer, July or August, and very hot. I’m in Tangier with my older brother, Abdelk'bir, and my little brother, Mustapha. Only the boys of the family on this vacation. We left the sisters and the parents in our meager house in the town of Salé [located on the northwest coast, next to Rabat], and we are here, in the North, in this territory that doesn’t seem to belong to the Morocco where we’ve lived since my birth in 1973. Tangier is Morocco and it’s not Morocco, familiar and not. It’s a double, troubled space, like me, a little gay teenager, still very effeminate despite myself, with a nearly definitive sense of shame.

Abdellah Taïa

My big brother has for a long time been the king of the family. A king who found a job a year ago and who has just earned his first paid summer vacation. He could have gone to Tangier alone, but he decides to bring along his two brothers. We are delighted, Mustapha and I. The little ones will travel with the king. They will do everything he wants. We will be his servants. And when he goes to sleep, we will start our revolution.

We are not far from the Port of Tangier, in an old hotel inhabited by strange, incomprehensible spirits. Our older brother doesn’t have enough money for a decent hotel. But it’s an adventure, he says. The life of the poor has that going for it, at least: the lack of means transforms you into a great dreamer. Anyway, money isn’t the most important thing. That’s Abdelk’bir talking again. But we know he’s lying. Poor or not, though, we don’t care. We are with our big brother, we sleep and eat with him. We follow him everywhere. And despite his silence, we love him. A mustached man, when he speaks, whether we agree with him or not, we listen. We want him to succeed. Through him, one day we will get out of poverty.

Going on this trip with him is exactly like one of these marvelous old Egyptian films that I watch every Friday night on RTM (Radiodiffusion Télévision Marocaine). I look forward to them all week. When these films appear on our little screen in black and white, I more than admire them: I enter into them. It’s like I’ve been living in an Egyptian film since 1980. There’s singing, dancing, crying, shouting. Sublime women, tough men, lovable thieves, romantic killers, too-old children, dancers with radiant bellies, poet-beggars, such beautiful singers, scenes so close to our own lives, to mine, to our collective poverty. Dialogues in Arabic that we all understand. Even my mother, who never went to school, she understands this Arabic pronounced the Egyptian way. Films that share our smells and our arguments. Our desires, our sufferings, our injustices, our obstacles, our love. Our sex. We are far from Hollywood movies and far from the films of François Truffaut. Far from Rock Hudson (whom I’ve adored since seeing him one night, by chance, on Moroccan television in Douglas Sirk’s All that Heaven Allows), far from Catherine Deneuve. We vibrate in front of and inside of these Egyptian images that, literally, save us.

Even now if I concentrate for a few seconds, I can recite the titles of these films that come from a half-century away. Sublime titles like Love Does Not See the Sun, The Beginning and the End, Where Is My Mind?, All My Life, No Condolences for Women, Bitter Day Sweet Day, A Woman on the Margin, Love Before Everything. I recite them again, again. And everything is still here, in my heart, my body, so strong. The images are either black and white or flamboyant Technicolor. Stories to evoke dreams and tears. The actresses Souad Hosni and Hind Rostom, who fall and pick themselves back up. They cry and they dance at the same time. And I along with them. I live with them. We watch the actors Farid Shawqi and Imad Hamdi and Kamal El-Shennawi, who are so handsome. But be careful. Always beware of men.

Salvation Army

The little gay child I still am at the age of 50 is eternally grateful to these old Egyptian films. Even though they do not directly broach LGBTQ+ subjects, they had a profound understanding of suffering and political abandonment, solitude and misfortune, wandering and tears. But through that sadness and despair we find the power to smile, to remain standing, to eat, to devour through the mouth and the eyes, the energy to live despite all those who want to stop us. I managed to survive because these Egyptian films crossed my path and created a magnificent upheaval in my heart, an utterly necessary revolution. A revolution that I would carry out one day. In endlessly replaying those films in my head, they came to dominate my imagination and my sensibility. I was rewriting them with complete freedom.

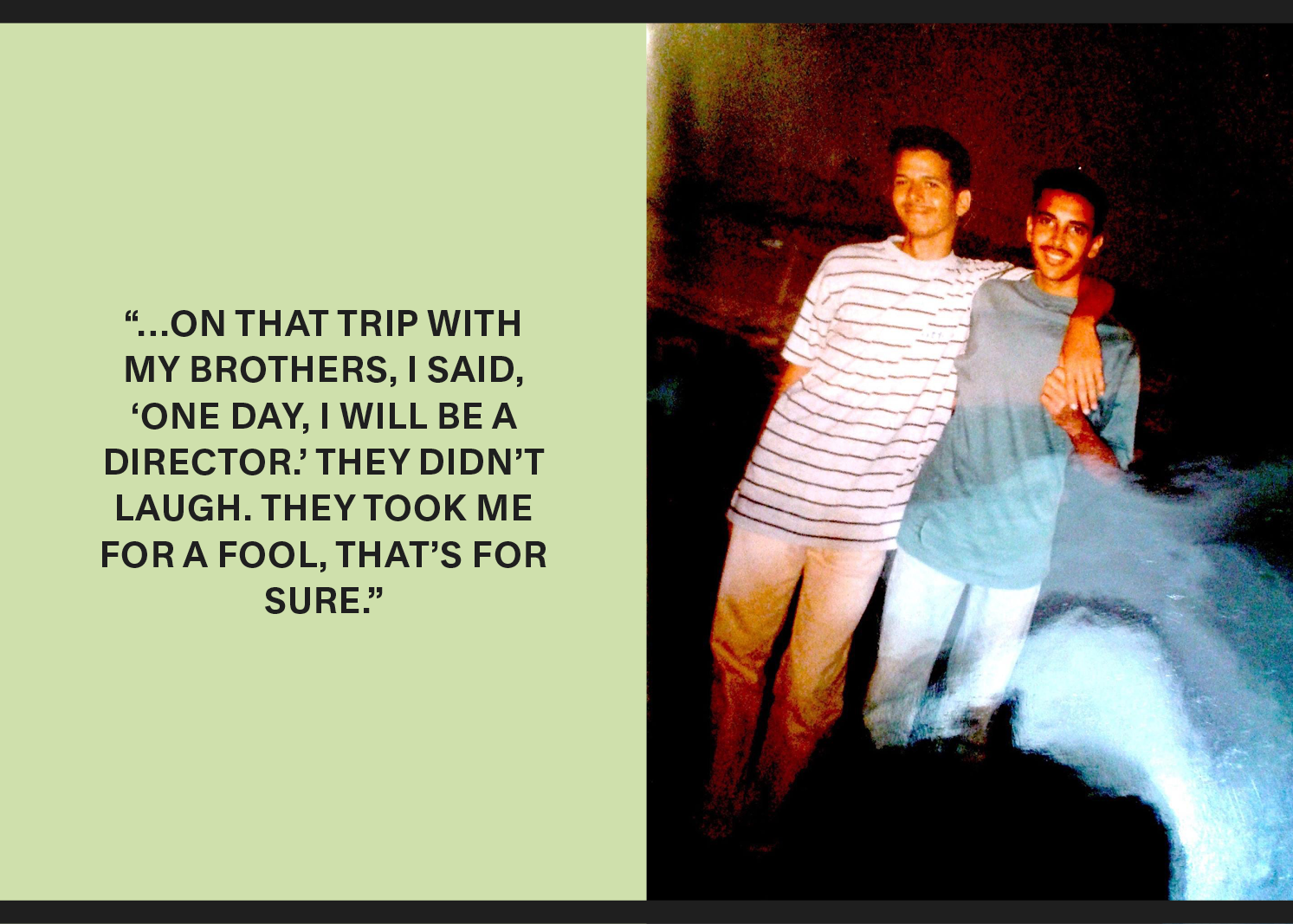

Thus, on that trip with my brothers, I said, “One day, I will be a director.” They didn’t laugh. They took me for a fool, that’s for sure. But they always considered me a fool, and that didn’t bother me. I am thankful to them for not laughing because they didn’t trample my little adolescent dream. In Arabic, to say director, we use the word mokhrij. This word literally means “one who brings things out.” One who comes out. One who brings things out into reality. One who bridges dream and reality. Dream-Reality: It’s the same thing.

Tangier, too, had that effect on us. The city created openings in us and between us. The world suddenly seems a place without borders and without words that wound, without arrogant rich people, or ex-colonizers who come back to re-colonize us (for our own good, they swear). Without the gaze of power that never stops interfering in our minuscule lives to direct us, subject us, condemn us. Back then, I didn’t know anything about Tangier and its literary myths. I didn’t know about Paul Bowles and his clique parading as chic bohemians among Moroccans who didn’t have anything to eat. I didn’t know that Tangier had been transformed by certain Westerners into a place to shamelessly live out their Orientalist dreams and their sexual fantasies. The Moroccan boy is made for that, a prized sexual object. I didn’t know that French and Spanish colonialism still existed in that city. I didn’t see it. I was drawn by the body of the older brother. In the dream, a gay dream.

It still makes me shiver, here, now: me writing these words. It’s a gay dream, like one that might play in one of the Egyptian films I loved so much.

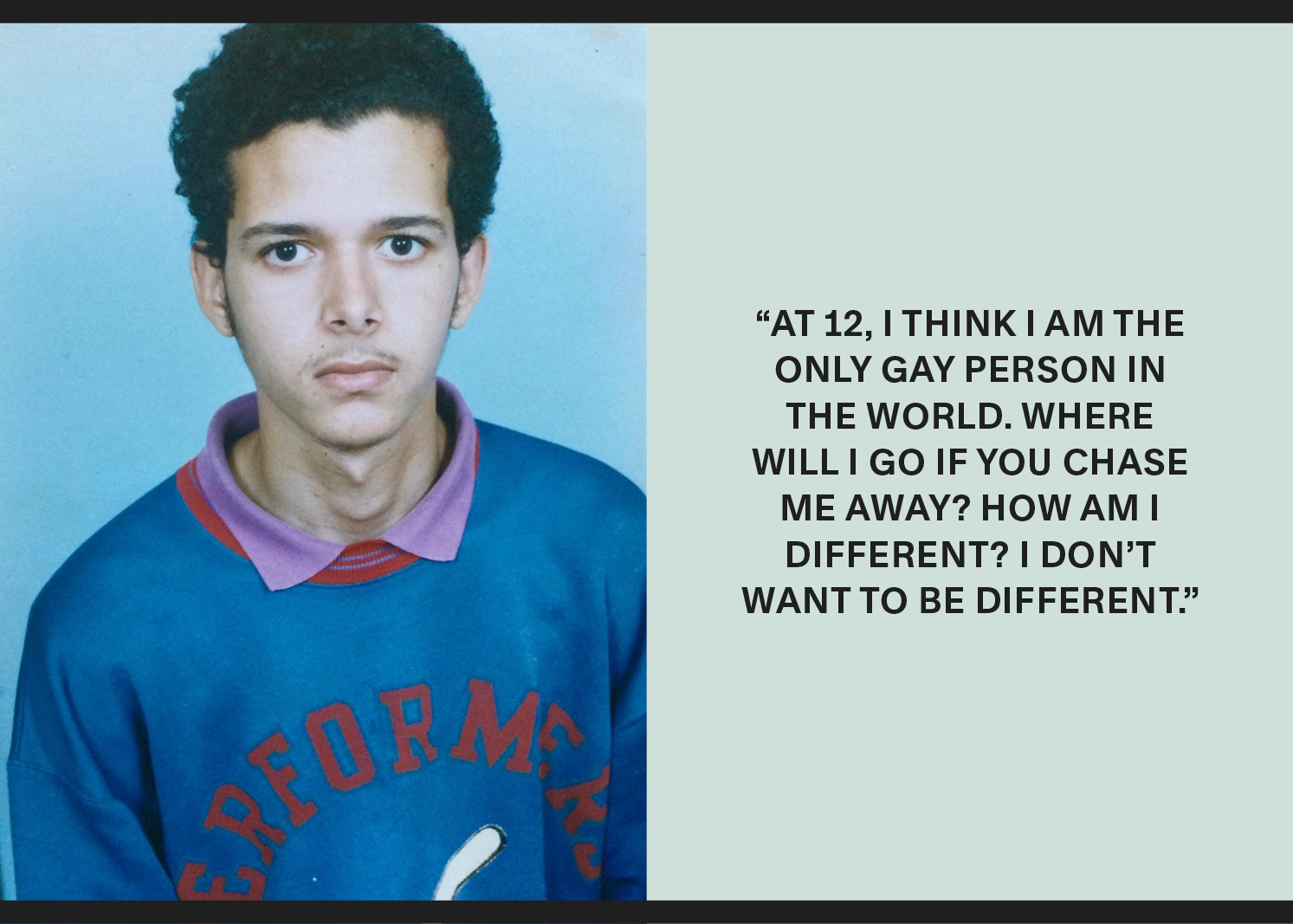

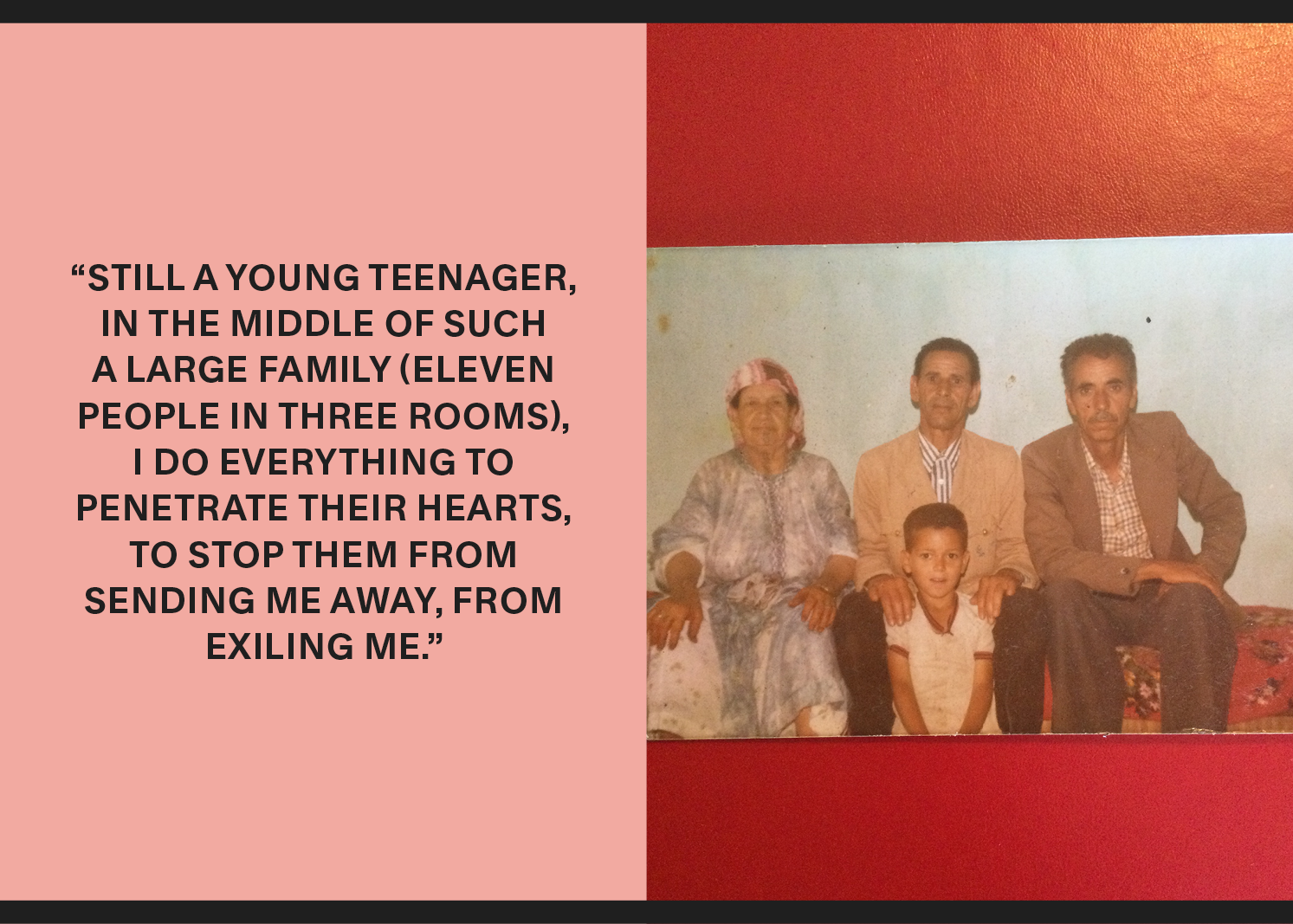

Still a young teenager, in the middle of such a large family (11 people in three rooms), I do everything to penetrate their hearts, to stop them from sending me away, from exiling me. From saying harsh words to me. At 12, I think I am the only gay person in the world. Where will I go if you chase me away? How am I different? I don’t want to be different. No one made me like this. Remember, it’s you who so loved my little belly dances when I was 6 years old. I would dance. I would shimmy. My butt. My legs. My raised arms. Little boy and little girl at the same time. And at the end of my performances, you would give me money. That made you happy. Did you forget? How could you forget that beauty between us, that revolution between us? That happiness…

In Tangier, I say it again: I want to be a director. Mokhrij. And deep down, I know: I am gay. It wasn’t a phase, a stage, a little path you go down before finding your definitive sexual place and identity. No. It is how I am, a frightened teenager who has to confront an entire society. A neighborhood. A country. But to become a director. Mokhrij. In Tangier, outside of our everyday life, my two brothers did not laugh at my dream.

In 2012, I was finally able to direct my first film, Salvation Army, a story based on my novel. It follows a teenager named Abdellah, like me, in his struggle to exist as gay within his family, within his first world: Morocco. He has no desire to leave this world or these people. He keeps latching onto them, forming connections with them. But he is alone. He wanders alone. He goes alone. He can be mean sometimes, too, like the others. Mean in order to resist. And when he finally emigrates, to Geneva, it will not taste like freedom. No. The West has another prison and another solitude in store for him.

By some miracle, I was able to shoot this film in Morocco. The authorities gave us their official permission. And the Moroccan actors and technicians were marvelous, united. Never did they judge me. They all understood that this film was telling an unprecedented Arab story, and that they had to help me film it. Proclaim it loudly, proudly. Salvation Army was screened at several film festivals in 2013 and 2014: Venice, Toronto, New Directors/New Films, Angers and more. But it was the screening in Tangier, at the Cinéma Rif in February 2014, as part of the Festival National du Film, that most impacted me. The film was in competition. I was there to watch the official screening. With Moroccans. Like me. That day, at the Cinéma Rif, the audience laughed, a lot, too much. Laughs that kill. Laughs that want to reduce to nothing once more the person who, despite everything, has managed to do something with his life, with his suffering, and with his Egyptian dreams. They were laughing hard, those mean Moroccans. They were laughing because they were embarrassed to be there, forced to watch it, that gay film, that reality they could no longer ignore. That reality was their reality, too.

They were laughing.

And the more they laughed the more I thought of my two brothers and me in Tangier. That beauty and that opening between us so long ago.

Laugh if you want. It will not kill me. Laugh. Laugh. Laugh. Show me how they programmed you to kill the dreams of others. To trample the weak. Laugh. Laugh.

Me, I am still and always watching Egyptian films. Forever in Egyptian films.