Code Breakers

By Christina Newland

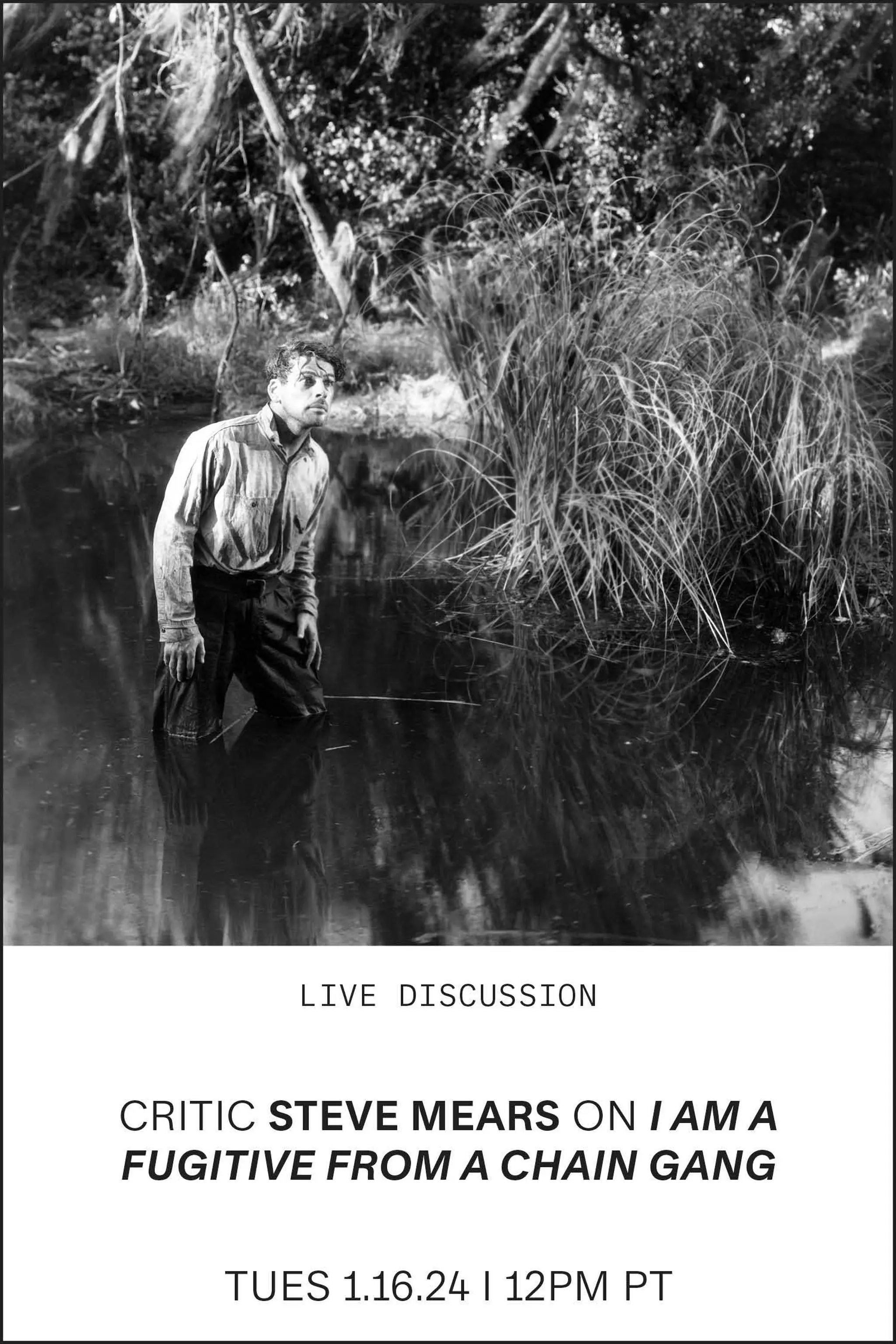

I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, dir. Mervyn LeRoy, 1932

code breakers

In the brief window before censorship took hold, Hollywood was permitted a bracing candor

By Christina Newland

January 15, 2024

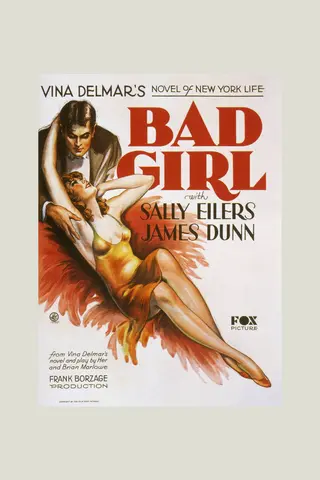

“Cheap and shoddy writing about cheap and shoddy people,” went the sniffy assessment written by the Hays Office in response to the source material for Bad Girl (1931), a picture under development. If any line might so easily reveal the disdain that the Hollywood film censors of yore held for their audience, this might be it.

The year was 1928, and the American film industry understood the immediacy and power of the newly talking motion picture. A battle for the soul of the medium would soon be waged over the matter of hemlines and innuendos, charming safe-crackers and bank robbers, and what their proper depiction should be for the moviegoing public. By 1934, at a financial and practical tipping point, the major studios acquiesced to the Hays Office, imposing more than 30 years of self-censorship.

From left: Paul Muni in I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang; Bad Girl, dir. Frank Borzage, 1931

For the uninitiated, one way to think of the Hays Office’s Motion Picture Production Code, or Hays Code, along with its creators and its enforcers, is as people who saw themselves as forceful cinematic nutritionists, obsessed by ensuring all moral deficiencies were excised. In truth they were more like fad-diet hucksters, totalitarian and exhausting in their constant production notes about the necklines of dresses, in their demands that all criminals be punished, that no racially mixed romance should occur, and that divorcing couples reunite, among other things.

The motion picture industry, still in its relative infancy, had long drawn ire from pearl-clutching religious groups and would-be boycotters. But in the Depression era, the cultural romanticization of street hoods (better to take what you need than be helpless on a breadline, after all), and the growing, paranoid terror that film might influence the behavior of the tenement classes, all eventually led to the American film industry’s self-censorship in 1934. Thus the pre-Code films—referring to Hollywood output in the brief period between 1930 and 1934—have become associated with freewheeling and licentious pleasure, be they musicals (42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933), gangster pictures (Scarface) or dramas (A Free Soul). With its ability to focus on quarrelsome dames, fly-by-night ne’er-do-wells, showgirls and bootleggers, pre-Code productions told audiences that crime did pay (at least for a while). To see the usually heroic Clark Gable as a vicious kidnapper, or the respected Barbara Stanwyck as a girl who believes in sleeping her way to the top, would remain a very fleeting opportunity in American movie history.

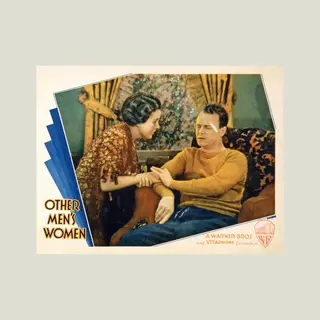

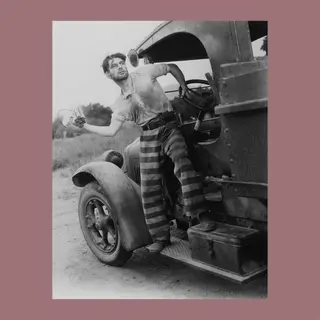

From left: Other Men's Women, dir. William A. Wellman, 1931; still from I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang

“With its ability to focus on quarrelsome dames, fly-by-night ne’er-do-wells, showgirls and bootleggers, pre-Code productions told audiences that crime did pay (at least for a while).”

William A. Wellman and Mervyn LeRoy were two directors with experience on the street: swaggering types with colorful backgrounds as aviators and newsboys, macho characters in the hothouse environment of the early talkies. LeRoy would be responsible for two stone-cold classics of the pre-Code era: Little Caesar (1931), borrowed directly from the antics of roving Chicago gangster Al Capone, and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), starring Paul Muni as an impoverished World War 1 vet whose story of prison brutality and unemployment spoke to the social concerns of the era. Wellman, meanwhile, was incredibly prolific in the fashion of many of his studio-era peers—Other Men’s Women (1931) is not as well known as his The Public Enemy from the same year, but it does also feature a top-of-his-game James Cagney, with prizefighter’s mien and pugnacious growl. In Other Men’s Women, Cagney plays a supporting role, with Mary Astor in the main, trapped in a love triangle between her husband (Regis Toomey) and his hard-living pal (Grant Withers). Cagney and Astor personify two sides of the Great Depression–era coin for stardom: down-to-earth and sophisticated. He has the earthiness and she the effervescence; he a hardness, she a knowingness. But they are both playful in their bad behavior in films like these.

Design for Living, dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1933

If I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang and Other Men’s Women initially seem like very different beasts, that is indicative of the pre-Code title. It’s not a genre so much as a description of what Hollywood’s finest were allowed to get away with for a brief time, like recalcitrant teenagers smoking behind a garden shed. The films also share a fast, rough-hewn contemporaneity: They are about the now in American life, and unlike many of the period-set stories that came both before and especially after, this was a time when modernity was king. It’s fascinating to see a period when there was little need to transpose the issues of the day onto a metaphorical historical basis. Consider the leftist politics of the Gary Cooper Western High Noon (1952), or the sexual one-upmanship of screwball comedies like The Philadelphia Story (1940), which exchange foreplay for witty repartee. It’s here you begin to see how much of Hollywood history is about smuggling provocative ideas into another form, and how much that is due to the influence of the censor.

Just a test sample of protagonists from pre-Code movies: a marijuana-smoking thief, played by William Powell, who happily scarpers with a Viennese aristocrat’s bored wife (Jewel Robbery, 1932); a young woman who considers an illegal abortion and isn’t summarily punished (Bad Girl, 1931); another who decides the best way to live is to move to Paris and cohabit with two of her handsome lovers (Ernst Lubitsch’s classic ménage Design for Living [1933], based on a play by Noël Coward and starring Cooper). If this all seems too modern for a time before the common ownership of a television set, that’s no coincidence: Modernity suffered when censorship arrived.

From left: Jewel Robbery, dir. William Dieterle, 1932; poster for Bad Girl

Ultimately, it’s telling that generations of moviegoers in the aftermath of the Hays Code are guilty of feckless nostalgia about bygone Hollywood. The false idea that the lacquered film stars of yesteryear belonged to an uncomplicated and morally upright world is still common—the impression that they may have drunk and smoked, but they certainly didn’t swear or have sex out of wedlock or cheerfully divorce without repercussion. The puritanical diktats of the Code in 1934 would forever offer viewers the dangerous chance to see the past as a rosier, simpler, “cleaner” time. But the vivacious, prurient, progressive and rebellious pre-Code era gives lie to that belief. Instead, it says something else: People always did like getting their hands dirty.