Crying With Mia

By Lisa Rovner

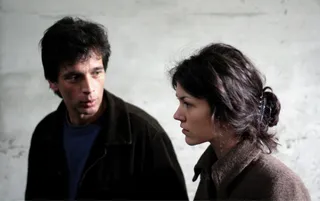

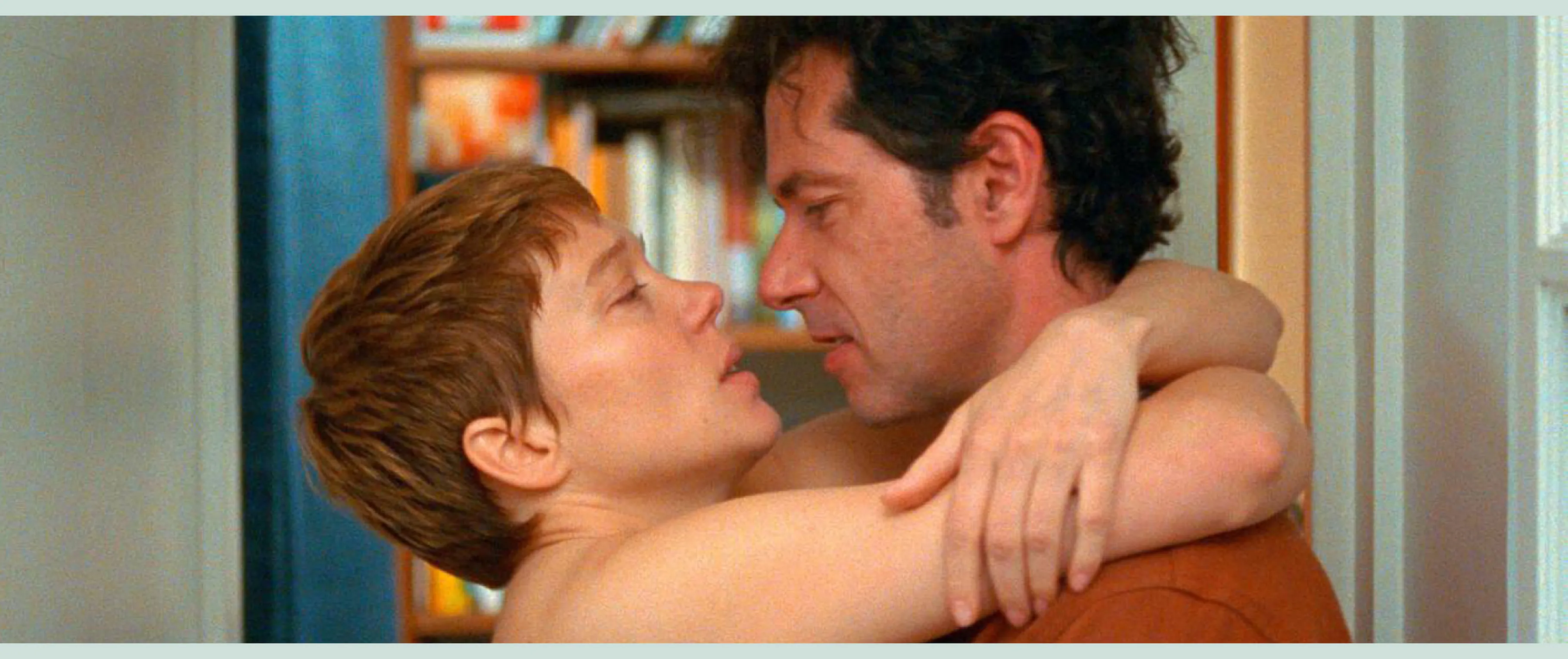

One Fine Morning, dir. Mia Hansen-Løve, 2022

Crying With Mia

By Lisa Rovner

The profound effect of director Mia Hansen-Løve’s anti-manipulative cinema

January 10, 2025

Mia Hansen-Løve

All of French filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve’s eight feature films have moved me to tears, a testament to the raw and profound emotions that define her work. Her first encounter with cinema came at 17, when she was cast in Olivier Assayas’s Late August, Early September (1998), a project that would set her on a path to filmmaking. By 26 she had written and directed her critically acclaimed debut feature All Is Forgiven (2007), which premiered at Cannes and established her signature style of drawing from personal experiences.

But what really sets Hansen-Løve apart is her masterful use of understated aesthetic realism and her nuanced approach to storytelling, which creates honest, flawed and unforgettable characters. In a conversation at her home on the outskirts of Paris, she describes her work as a response to the stereotypical “strong female leads” of contemporary cinema. Collaborating with celebrated actresses such as Isabelle Huppert, Léa Seydoux, Vicky Krieps and Mia Wasikowska, Hansen-Løve brings to life complex, relatable women navigating the tumultuous terrain of life and its upheavals. Her protagonists offer a stark contrast from the one-dimensional archetypes; instead, they are richly drawn, their vulnerabilities laid bare in a manner that feels both intimate and expansive.

![]()

Things to Come, dir. Mia Hansen-Løve, 2016

![]()

Goodbye First Love, dir. Mia Hansen-Løve, 2011

Your films draw heavily on your own life, yet I’ve heard you resist the term autofiction. Why is that?

I don’t reject the term itself, but I don’t feel like it applies to my films. For example, my first feature, All Is Forgiven, was a very free take on my uncle’s life. My starting point was his story as it was told to me in my adolescence, but then I transformed and reinvented it. When I’m writing, I use what I know as much as what I don’t know, which is why I don’t think “autofiction” is a proper characterization of my work. What interests me is the essence of reality, and I draw on it to create a new story. A telling example of that would be my film Bergman Island [2021]. Unlike the protagonist of that movie, I’ve never been to the island of Fårö with my daughter’s father [Olivier Assayas]. The story is completely made up. But that doesn’t mean it’s not truthful and doesn’t convey an aspect of my own experience. Again, it’s about condensing and reinterpreting reality through the tools of cinema. Deep down, this process of transformation is what excites me the most as a filmmaker.

In your most recent film, One Fine Morning [2022], protagonist Sandra, portrayed by Léa Seydoux, is an interpreter. The word interpreter is derived from the Latin interpretari, meaning “to explain, expound, understand.” As a filmmaker, do you see yourself as an interpreter or exegete?

It’s true that Sandra’s profession as an interpreter is a perfect metaphor for what I do. But I would use the word interpreter in the sense of “translator” rather than “exegete.” As a filmmaker, I translate my life experience into fiction and images as a way of transforming the ephemeral into something permanent. Filmmaking for me is a fight against oblivion.

In the contemporary film landscape, there is a vogue for “strong female leads.” However, frequently these characters simply mimic traditional masculine archetypes and modes of behavior. In your films, what defines a truly strong female protagonist is a richly layered, multifaceted portrayal that does not outright reject qualities historically deemed feminine. Is this a conscious consideration in your writing process?

I think it’s just a testament to my sensibility—an expression of who I am. Like me, the female characters in my films are sensitive and vulnerable and don’t try to imitate men. There’s something a bit ironic about our so-called feminist era. On the one hand, female characters are more than ever present and put in the spotlight in movies. But on the other hand, there’s this idea that feminism in cinema should be about reclaiming the codes of masculinity. In the case of One Fine Morning, some people reproached my heroine, Sandra, for being weak because she chooses to have a relationship with a married man. The fact that she waits for him was perceived negatively, as a form of submission, even though he eventually chooses her [over his wife]. People said to me, “She’s not the kind of woman we want to see onscreen today.” There’s this idea that the kind of woman audiences want to see onscreen today is a strong woman rather than one who agrees to suffer in the name of love.

Mia Hansen-Løve in Late August, Early September, dir. Olivier Assayas, 1998

“Filmmaking for me is a fight against oblivion.”

What sparks your writing? Where does it all start—with an image, a line of dialogue, a character, a dramatic situation, an object?

It starts with a character’s destiny. It’s not a story with a beginning, a middle and an end but more like a movement, a direction, an arc. My films are never about a good idea, the way you might hear someone say they have a good idea for a film. Often we see films that are driven by an idea, a story. For me, that’s never the starting point. I start with a sense of momentum in connection with a character. It’s something very delicate, almost abstract and difficult to grasp. It’s not something that can be easily pitched.

You have a remarkable ability to translate the inner life of your characters onscreen. Is the empathy that’s so present in the final film already in the writing?

I’m obsessed with creating a film language that evades the kind of manipulation that’s so typical in cinema. I write films to watch characters move through life. I don’t write lines to tell the audience what to think and what the characters are thinking or what their intentions are. I feel like when you do that, you strip the characters of their subtext. By refraining from overtly explaining the psychological motivations behind characters’ actions, you create an inner life for them, which in turn fosters a deeper, spiritual connection between the audience and characters. That’s something I work on in the editing, too, but I don’t play with duration to convey a sense of inwardness. My cinema is not one of overextended shots. I think the introspective quality of my films stems from the way I look at characters go through life. For example, I’ve been told many times that I often film characters walking in the street, opening doors, entering buildings, going up stairs, etc. These kinds of moments can seem useless or empty, but they’re precisely when something interesting happens on an actor’s face. In One Fine Morning, when I show Léa Seydoux walking in the street or riding the bus, I’m capturing a side of her that we haven’t seen before.

Your films exhibit an unwavering commitment to character-driven narratives: We follow a single protagonist who appears in most scenes, generally in the center of the frame. I know you don’t think of yourself as an actor, but do you think that your experience in front of the camera in films by Olivier Assayas has shaped your approach of foregrounding character?

It has certainly informed the way I make films. I was only 17 when I acted in Late August, Early September. I was very shy and had never acted before, so I was terrified. But at the same time there was something incredibly liberating about being propelled into fiction—into somebody else’s fiction. It’s difficult to say what I would have become if I hadn’t acted in that film. It was a very powerful experience that made me discover cinema and shaped my relationship with it, including my willingness to write characters close to myself.

But I’m also very much defined by the fact that I didn’t go to film school. For me, cinema is the equivalent of playing hooky. It’s about freedom. So I’ve always fiercely rejected the academic way of making movies. And I’ve never tried to make films in the style of another filmmaker. My early films have a clumsiness to them, there’s almost no technique in them. I picked up technique progressively through doing. Another thing that defines me as a filmmaker is my commitment to shooting films in actual locations rather than in studio sets. That’s something I might have felt differently about had I gone to film school.

How important is place to your stories? What is it about a place that inspires you?

I always gravitate toward places that I find have soul. I like places that are multilayered. For example, I shot Goodbye First Love [2011] in the Haute-Loire and Ardèche, in south-central France, where I used to spend my holidays. Those places are loaded with memories for me. That’s what I look for in a place—a juxtaposition between the present and the past, a feeling of hauntedness. Places are as much the starting point of my films as characters are. When I started writing Bergman Island, I didn’t know where the film would go and what it would look like, but I knew I wanted to center it around a filmmaker couple and the island of Fårö. The island would be like the film’s third protagonist. I wanted to confront that filmmaker couple with this island and load it with deeply personal things.

Do objects lead to scenes in the same way places do? I’m thinking of the hat in Goodbye First Love; The End, a book of poetry by Robert Creeley, in Eden [2014]; the Bibi [Andersson] sunglasses in Bergman Island; and your father’s books and journals in One Fine Morning.

For me, objects are at the heart of cinema. I see them as intersections between the living and the dead, between the visible and the invisible. That’s something I felt intensely when I was making my second feature, Father of My Children [2009]. It’s a film about a producer who passes away, leaving behind objects, like film cans and posters, that become substitutes for himself. Objects are loaded with presence. When captured by a film camera, they offer a window into the invisible spiritual world. The hat in Goodbye First Love is a metaphor. It’s a door into the past and imagination—into the mystery of life. It’s the same with the books in One Fine Morning and the sunglasses in Bergman Island.

All Is Forgiven, dir. Mia Hansen-Løve, 2007

Your films don’t show us characters at the height of their careers or relationships: Isabelle Huppert’s Nathalie in Things to Come [2016] has just been left by her husband, and Chris [Vicky Krieps] in Bergman Island is mired in a creative slump. We meet them at their most vulnerable and watch as they grapple to understand themselves, their relationships and the world they inhabit. And they don’t always win, but it always feels honest. You talk about truth a lot—how do you go about capturing that truth? How do you work with actors?

I don’t have a scientific method that I apply dogmatically to each film. If I do have a method, I keep adjusting it according to the sensibility of the actors I work with. You can’t work the same way with someone like Isabelle Huppert, who’s acted in [more than] 90 films, and a three-year-old. When I’m working with kids, I try not to give them any lines or I help them learn their lines through play. But I never give them lines in advance. On the other hand, when I’m working with adults and young adults, I’m very precise. I don’t leave the actors with a lot of room for improvisation, which doesn’t mean they have no freedom or space to exist. And I don’t rehearse much with them, either, because my scripts are very impressionistic: They’re made up of brief scenes that resemble brushstrokes. How could one rehearse things like strolling on the beach, bathing, driving a car, riding a bike, visiting a house, et cetera? Unlike what people may assume, my films have relatively little dialogue. I don’t write dialogue-driven scripts. Actors who are really into performance wouldn’t enjoy working with me. An actor who works with me won’t say to themself, “I’ve outdone myself—I’ve surpassed my limits.” They won’t lose 40 pounds. They won’t sweat.

You use the word transparent when you describe your filmmaking style. What do you mean by that?

The idea of transparency is misleading because style can never be completely transparent. But it’s a feeling I try to convey. I don’t film shots for people to say, “Wow, what a shot!” I try to create shots that don’t come between the characters and the audience. I want my shots to be at the service of the film, its rhythm and characters. I don’t want them to be noticeable. But that doesn’t mean I don’t think about the mise-en-scène. On the contrary, I spend a lot of time thinking about it: on my own but also with my script supervisor, Clémentine Schaeffer, who’s one of my closest creative collaborators. We take photos of each other acting out the scenes. We try to find the rhythm and movement of the scenes so that they feel organic and nothing in them feels forced. It takes a lot of work to achieve that.

“There’s this idea that the kind of woman audiences want to see onscreen today is a strong woman rather than one who agrees to suffer in the name of love.”

The question of what gives meaning to our lives is one that you’ve said obsesses you. Is this what filmmaking is really about for you? After eight features are you any closer to the answer?

I think that if I were any closer to the answer, I would stop making films. I guess that’s what keeps me going. I don’t have any answers—only questions.