Dressing Like Deneuve

By Leanne Shapton

Dressing like deneuve

words and illustrations by Leanne Shapton

Origins of an Ungaro obsession

September 2, 2022

AUTHOR READS

“I don’t love you,” says Manon.

“Perfect,” says the man. The models on the catwalk pivot, stand and stop. Manon, the man, and her brother sit in a row of white chairs, watching.

“Do you like dresses?” the man asks Manon. She stares at the stage and bites her lip. He whispers in her ear, “This dress was made for you.”

A model takes off a short, dark brown velvet coat to reveal a white lace bodysuit, cut low on the hip, with matching stockings worn high on the thigh.

Manon 70, dir. Jean Aurel, 1968

The movie Manon 70 (1968) was directed by Jean Aurel. It’s based on the scandalous 18th-century novel Manon Lescaut, by Abbé Prévost, a French priest and novelist who regularly deserted the monastery for the literary high life. He wrote the story as the seventh part of Mémoires et aventures d'un homme de qualité (Memoirs and Adventures of a Man of Quality). This seventh and final volume, Manon Lescaut, was forbidden in France (prostitution, murder, filial scandal, moral ambiguity) but circulated in pirated copies throughout Paris from 1731. Prévost’s story was so notoriously popular that Puccini wrote an opera based on it, first performed in Turin in 1893.

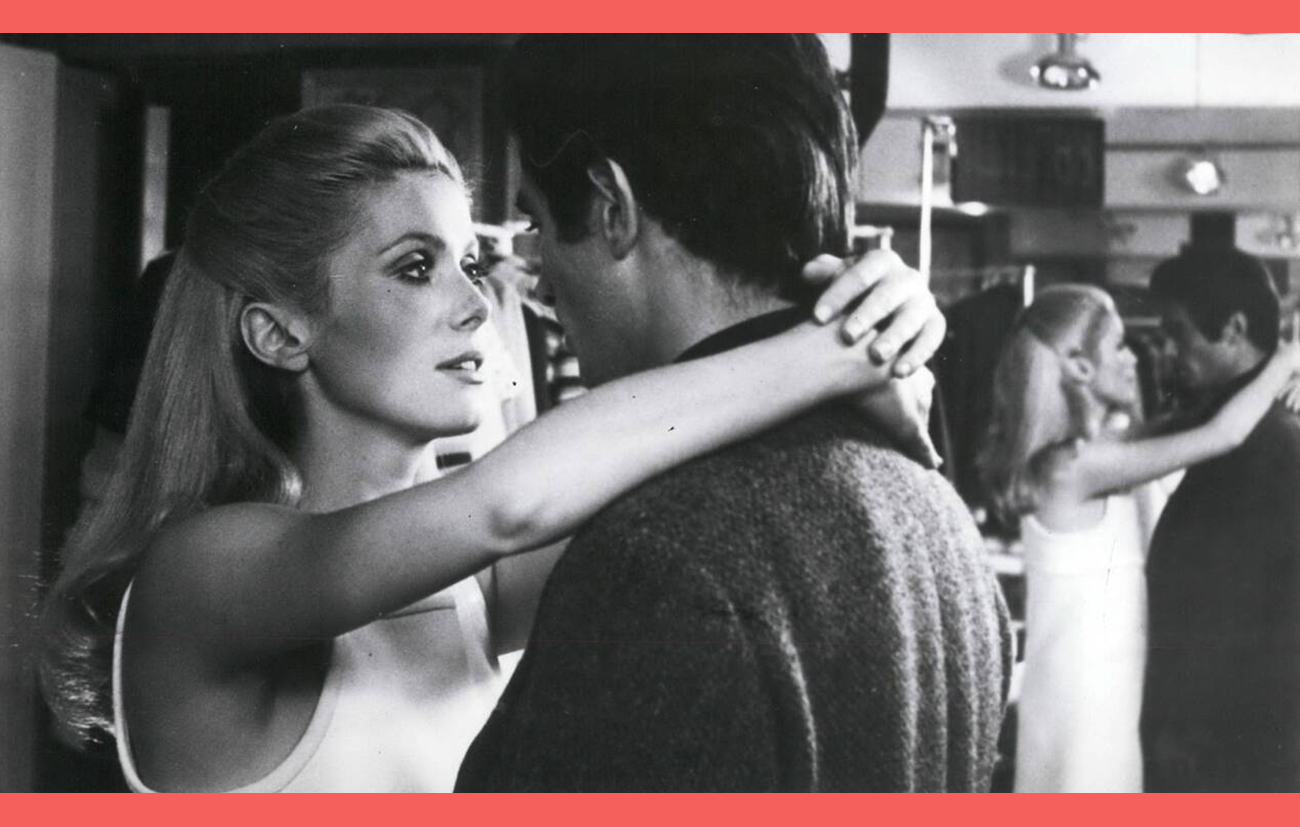

In the book, Manon, a woman of questionable integrity, dumps her impoverished boyfriend for a rich man who can support her taste for luxury. In the updated movie, set in late-1960s Paris, Manon dumps a series of rich boyfriends to support her taste for her impoverished boyfriend, François. Still, she keeps finding more rich boyfriends to support the luxuries that her poor François can’t provide. Manon is played by Catherine Deneuve, in a refrigerated performance of ponytail and moue. The luxury is played almost exclusively by clothes designed by Emanuel Ungaro, the French fashion designer. He dressed Deneuve’s Manon, and his 8th arrondissement atelier appears in the film.

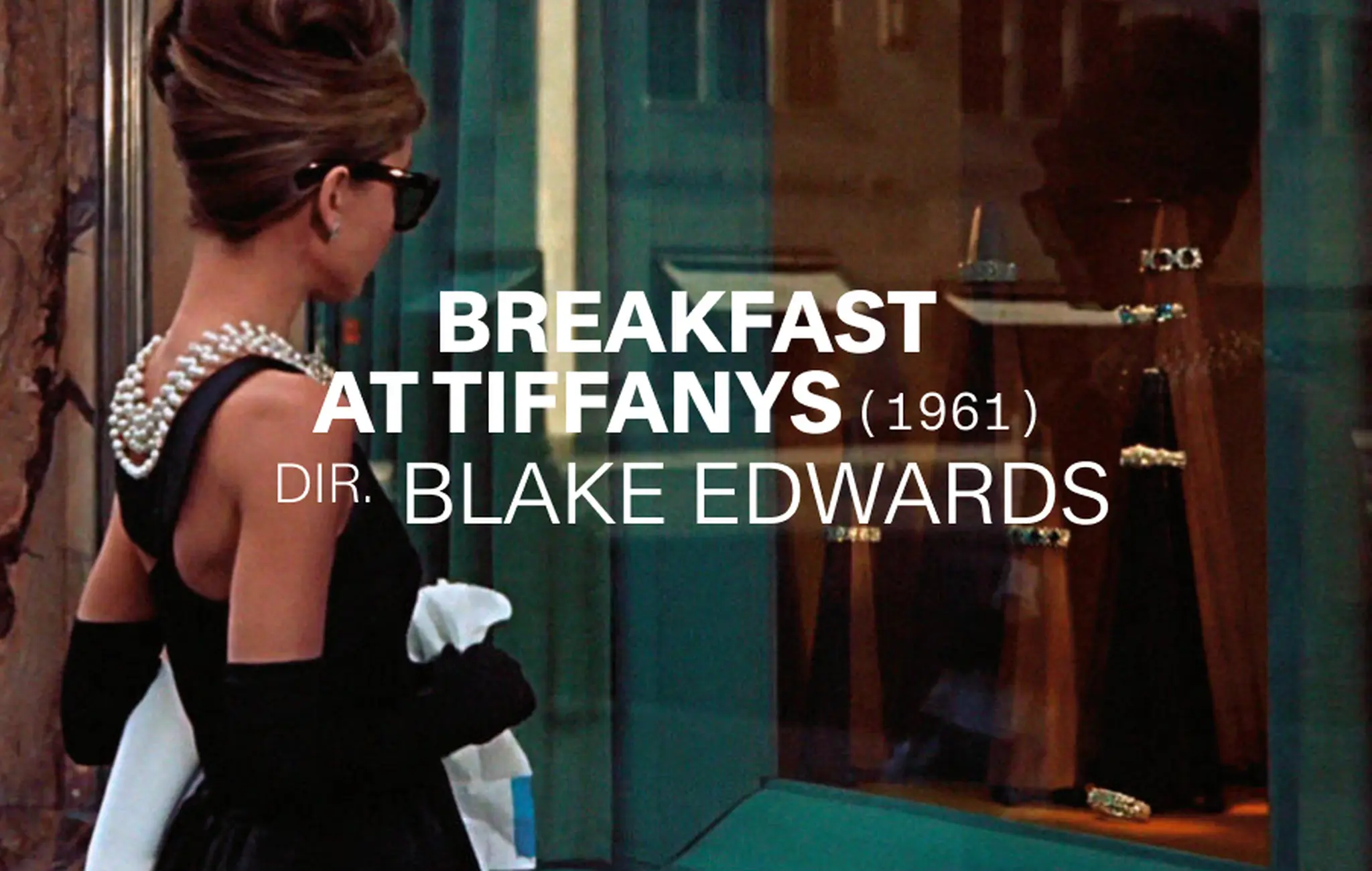

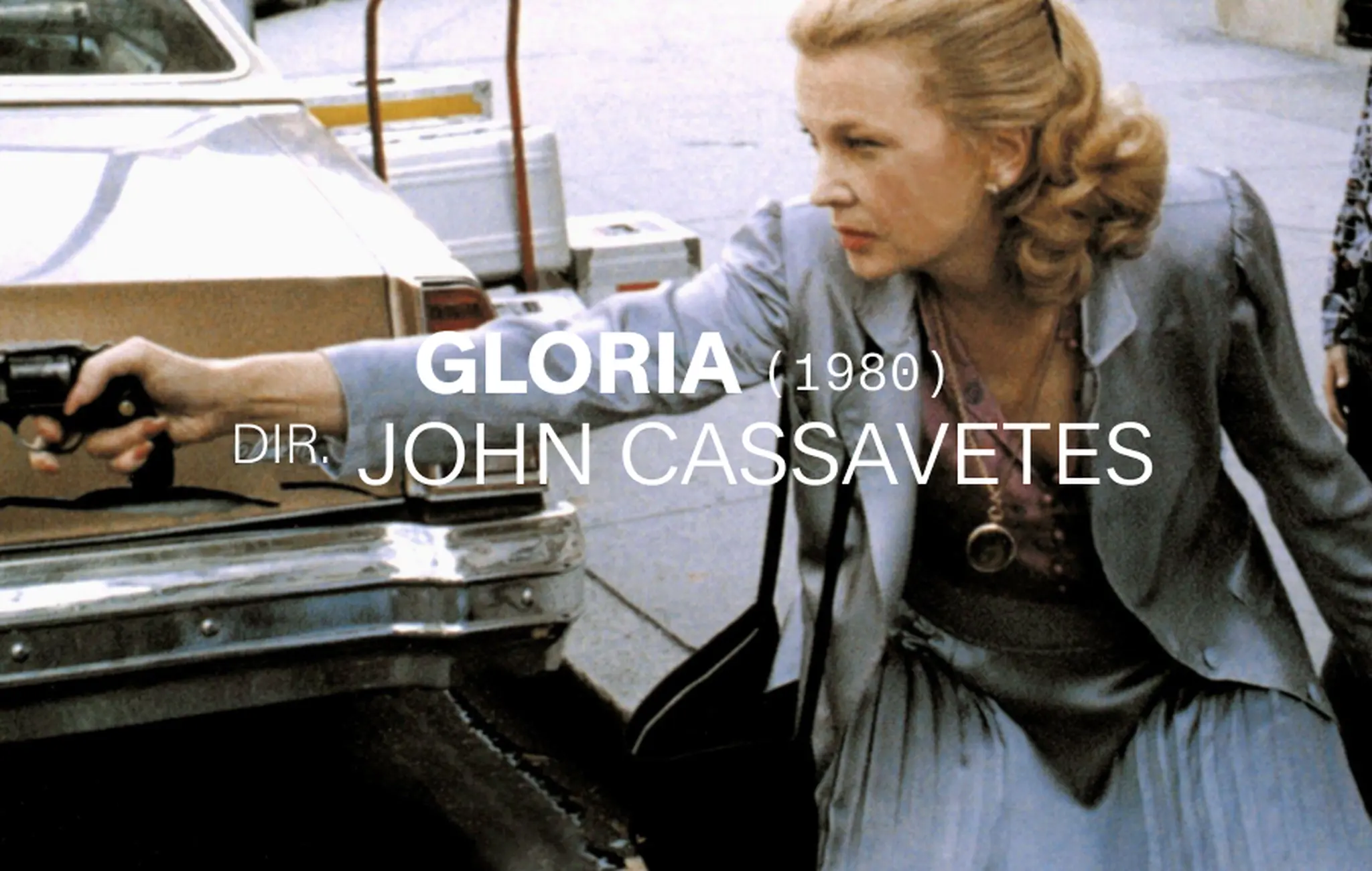

Following Brigitte Bardot dressed in Balmain for …And God Created Woman (1956) and Audrey Hepburn in Hubert de Givenchy for Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), Deneuve was part of a burgeoning trend of actresses dressed exclusively by couture designers for films. She had been dressed in Yves Saint Laurent for her iconic role as a prostitute in Belle de Jour (1967), which was shot the year before Manon 70. Deneuve went on the record to say that Aurel, the film's Romanian-born director, was “not at his best,” and the movie was largely considered a flop. After Manon 70, Ungaro continued designing for films, again dressing Deneuve in Jean-Paul Rappeneau’s Le sauvage (1975), along with Gena Rowlands in Gloria (1980), as well as a fleet of other starry talents (Isabelle Adjani, Marisa Berenson and Sharon Stone, among others) in auteur films for the rest of the century.

I first saw Manon 70 in 2011, two years into my marriage, and to Deneuve’s point, I immediately forgot everything about it. Except for the clothes: A-lines, humongous buttons, white boots, plasticky surfaces and orange wool. Modest but brief. Opaque and revealing. Féminin et un peu masculin.

I watch it again in 2022.

“I don’t love the movie,” I say to my boyfriend.

“Perfect,” he doesn’t say.

“Do you like dresses?” I ask myself.

“These dresses were made for me,” I whisper to myself.

Manon 70 is scored, in tinkling guitars and Vivaldi, by Serge Gainsbourg. (“Manon / Manon / No, you surely don't know, Manon / How much I hate / What you are,” his title track croons.) It follows a cautionary tale–slash–love story about a vain and selfish woman and the man devoted to her. On second viewing it remains unremarkable and a decade more dated: A bathtub rape augurs love, Manon gets slapped around by her boyfriends, men throw grunting punches and mutter pimpy things like, “I only question a woman when I know the truth!” There is furious chain-smoking and drab makeout sessions, more assault and deceit and cruelty … but the clothes, the clothes. In 1968, as in 1731, wanting clothes is a vanity, and vanity—like any sin—is a sign of life.

In a terrifically sad and attractive scene, Manon tells François (played by a glum Sami Frey) that he needn’t end things with her, that she is “working for us,” that her new suitor “is very rich and money has no value to him.” This exchange is shot through the display rails at the Ungaro Paris showroom, and the couple speak in profile, flanked by rows of bright, opulent clothes, mutton sleeves, wide cuffs and puff shoulders. There are tartans in pinks and reds, jackets in periwinkles, wool gabardines framing their faces as they move through the space, negotiating Manon’s position as ornament to the richer man. François slaps her face in front of a white openwork lace babydoll dress. She remains impassive, almost smiles. “I suspected you wouldn’t like it,” she says. He sulks in front of a mod coat in an orange windowpane check. She watches him, after glancing at an olive gown. Then, standing next to a robin’s-egg blue A-line dress, she says, “He travels a lot, we don’t have to break up.” The frocks swing gently on their hangers. They embrace. He unzips her shift, and the gorgeous dresses foreground them to the trills of a thin harpsichord gavotte.

Catherine Deneuve and Sami Frey in Manon 70

On second viewing I think less about the clothes and more about the price of things, the wages of sin, how we pay for what we want, hold on or let go, how to leave something when we still need the eggs. Manon is a nightmare. Her brother, who acts as a smirking trafficker of her wealthy suitors throughout, says: “Manon est une enfant, elle aime toute ce qui brille.” She loves everything that glitters. She does take a matter-of-fact responsibility for her desire for luxury, prioritizing it above feelings. She’s very affectionate, and it’s not cold, exactly—maybe just a little neurodiverse.

Freedom, to Manon, means loving two or even three men who can give her what she needs: clothes and attention. Manon wants Ungaro. She will forgo fidelity for clothes, she will ask the man she truly loves to do the same, until he can’t bear the lie and they wind up—in the French New Wave way—stumbling in bright sunshine through a construction site, barefoot in nondescript jeans yanked out of the cupboard of a speedboat. They hop a freight train and hitchhike from the outskirts of Nice back to Paree.

I think about the relationship that I was in when I first watched the film, where I was given things that glittered. Back in 2011, I noted the designer in the Manon 70 credits and began looking for Emanuel Ungaro pieces on Etsy, eBay and in vintage shops. There wasn’t much from the Manon era of the late ’60s and ’70s, but plenty from the ’80s and ’90s, up until Ungaro sold controlling stake of his house, and into the aughts—when Silicon Valley’s Asim Abdullah bought the brand for $84 million and Lindsay Lohan held the role of artistic advisor for a hot second.

In the early 1960s, as an up-and-coming young French designer, Ungaro had assisted Cristóbal Balenciaga and worked alongside André Courrèges. I can spot these modernist influences in the film’s costuming. In one street scene, Manon wears a buttered-popcorn yellow, Peter Pan–collared, wide-wale corduroy mini coatdress that looks straight out of a William Klein or Willy Rizzo fashion photograph. In another scene, she wears a perfectly plain black swimming tank, just a millimeter this side of Speedo but for the unusual height of the neckline. Then, with her sucre-père of the moment, she wears a long, bright solid-blue column dress. Both of these outfits could be Cristóbal Balenciaga at a squint. She sinks into a sofa. An odalisque of ambivalence while her toes are being nuzzled.

“A-LINES, HUMONGOUS BUTTONS,

WHITE BOOTS, PLASTICKY SURFACES

AND ORANGE WOOL.

MODEST BUT BRIEF.

OPAQUE AND REVEALING.”

In a scene whilst cuckolding her lover, Manon approaches a mirror in a narrow pink skirt suit, a modern upgrade on Jackie Kennedy’s famous Dallas Chanel. All of these, and indeed most of what Manon wears throughout, are simple, modern designs, not what Ungaro became well known for, at least to me: roiling frills, almost mumsy patterns and extremely feminine hemlines that broke me free of a vague, conventional unisexuality. Manon 70 proved to be my gateway to Ungaro, proceeded by a deep, devoted appreciation of his house, and a hard vintage habit. Within days of watching, I bought my first piece: a purple Ungaro bathing suit, probably late ’70s, ruched unlined cups, deep V, cut low on the hip.

A year later I had a baby. Another year later, postpartum, clear of elastane and shapewear but in the heaps of a disintegrating marriage and depression, I again took up looking longingly at vintage Ungaro pieces. I was crying a lot. My second purchase was a pair of Ungaro by Persol sunglasses. Then a strapless minidress, like a body-sized white and blue corsage, when I was desperate to feel held and important. That dress has since been sold at a yard sale, but I have a video of my daughter, age one and a half, spinning around the bedroom in it, then bursting into tears, then getting up and continuing to dance. By 2013, as adult and mother, my own freedom meant wearing whatever the fuck I wanted and being able to pay for it myself.

A lot of the Ungaro items for sale online were not attractive, even downright ugly, to me. Dark, heavy, middle-management ’80s pieces that illustrated the triangular bank-teller aesthetic of the time. Sometimes a sedanlike, almost Angela Merkel silhouette. But then I’d stop mid-scroll on a strange ruffled tent, a sexy chintz sundress, a high-shouldered, narrow-hipped cocktail, in a bizarre green-and-pink oysterlike print. The clothes themselves were not cool, but they looked somehow like an unrealized side of me; like women I liked to look at, like my mother, applying Diorissimo, her feet in suede Aldo pumps. She wore chiffon blouses and high-waisted slacks, crocheted butterfly tops, thin belts, pleats and jabots. The Philippine national dress, the baro’t saya, has high, exaggerated puffed sleeves something like Ungaro’s heavily shoulder-padded lines.

The clothes are not the definition of glamour, but manage to simultaneously signal the suburban Canadian mall and the Champs-Élysées.

Manon has zero power, except to play men’s love for her off each other in the expectation of more Ungaro. I felt I had little power in my marriage, my tastes in clothes were dismissed by my husband, and perhaps I turned to Ungaro in some sad, spendy attempt to love myself or prove my own eye and taste. The clothes became a warped adult version of Donald Winnicott’s transitional object, given outsize attention but helping me shift out of a dependent relationship.

I left.

My collection of vintage Ungaro grew. I wore a yellow heart-printed Ungaro onstage at Lincoln Center. I wore an Ungaro sundress to a tedious vernissage, an Ungaro mini to a board meeting, an Ungaro tuxedo jacket to a dinner party where I was seated next to one of my favorite writers. I wore a cashmere Ungaro camel coat on a train to Dijon with a sociopath. I wore a salmon acid-washed Ungaro to the Long Island strip plaza where I replaced my broken laptop. I wore a bishop-sleeved Ungaro for frozen palomas overlooking the East River, and an Ungaro jacket to my grandmother’s funeral.

I wore a lot of Ungaro to teach in, nervous in front of students who had read, written and metabolized more theory than me; the unacademic clash of big fat roses, mutton sleeves and purple damask gave me some weird blowsy confidence. I wear a prescription pair of Ungaro frames for reading, and a cat-eye pair in the sun. My purchases never break $200, and are often less than $50. There are plenty of expensive pieces to be had, but it’s the slightly under-the-radar, bog-standard Ungaro I’m after, and on balance, it’s affordable.

In Germaine Greer’s 2004 foreword to Prévost’s Manon Lescaut she describes Manon as a giggling minx and emotionally inert. Guy de Maupassant described her as combining the apparently contradictory features of being “nice,” “alluring” and “vile,” a “figure full of seduction and instinctive treachery.” This describes what I like best about how certain dresses or clothes can work. An inscrutable and mildly destabilizing outfit is, aesthetically, a great sweet spot.

My matriculation in Ungaro begat the designer’s own sartorial understudies. I developed a sharp eye for the cheaper knockoff Ungaro-inspired. Brands like Dawn Joy, Barbara Barbara, and Flora Kung ran with Ungaro’s ideas, shapes and prints, but in less luxe, more flammable materials. I’d been a fan of Arnold Scaasi—the Canadian designer who spelled his Jewish name backwards in a catwalk bow of faux-Italianate—since 1998. He dressed Deneuve, too, as well as Barbra Streisand. By way of Ungaro and Scaasi I found Victor Costa and Chloé-era Karl Lagerfeld, Murray Arbeid (a favorite of Princess Diana), and Ognibene-Zendman. After relying heavily on men’s clothes for the lion’s share of my wardrobe, the particular femininity (floral? ruched!) that these designers offered was the kind I could approach sideways, without the feeling of betraying any of my comfortable androgyny. Post-divorce, I showed more skin, not so much to reveal but to relax.

Manon 70 is about a woman’s pragmatic dependence on wealthy men. “Cette robe elle vous rassemble,” said the man to Manon: This dress suits you. It reminds me of the French phrase être chez lui, to be at home. Ungaro, in the absence of a home, suited me.

Twelve years later, Ungaro dressed Gena Rowlands in John Cassavetes’s Gloria—about a vehemently independent, maternally way ambivalent woman, on the run from the mob with Phil, an orphaned six-year-old boy, in tow. Unlike the pâtisserie-esque rows of dresses in Manon 70, Gloria’s Ungaros are worn multiple times, stuffed into a carpetbag or hung on the back of a door in a flophouse toilet and aired out along a shower rod in a New Jersey hotel. Gloria’s Ungaros are not carrots dangled, they elle rassemble, in that they support this sweating, smoking, pistol-wielding reluctant mother figure. A camel trench coat over light pink pajamas, black and red satin, a bright pink wheat-sheaf print. While I credit Aurel’s Manon for my introduction to Ungaro, Gloria’s shiny prints that pack heat, get flung into the backs of cabs, tear along New York avenues and hunch ruefully at bars are the Ungaros I know and quasi rassemble. The dress Gloria wears to negotiate her immunity at the apartment of a mafioso don is my favorite: a black floral-spotted wrap, sharp-shouldered, with a slash of yellow crossing the chest, an unintentional wink to a suffrage banner. The movie is about a woman’s pragmatic dependence on herself and her protection of a child.

“What are you wearing?” asks a reporter from The New York Times.

“Are you kidding me?” I reply. We’re at an Upper East Side art gallery, Thursday, a fundraiser for a literary quarterly. The attendees pause in front of the paintings, talk in clusters by the sweeping marble staircase.

“No, I’m not kidding,” says the reporter. I look at my shoes. They are very pointy, a wool black-and-white houndstooth check, with a kitten heel and neon yellow bow.

“Please don’t take my picture. But the shoes are Ungaro.”