Elevated Sounds: Kleber Mendonça Filho

By Kaleem Aftab

Neighboring Sounds, dir. Kleber Mendonça Filho, 2012

ELEVATED SOUNDS

Kleber Mendonça Filho on unorthodox listening, anti-procedures and David Lynch’s aural atmospheres

By Kaleem Aftab

September 1, 2023

Kleber Mendonça Filho’s debut feature, Neighboring Sounds (2012), was hailed as an instant classic, making it onto A.O. Scott’s New York Times list of top 10 films of the year and becoming Brazil’s submission for the Academy Awards’ best foreign language film. Situated in the beautiful northeastern coastal city of Recife, Neighboring Sounds is a tale of gentrification and capitalism’s destructive effect on communities. The director, a former film critic, uses his ensemble of characters to demonstrate the power dynamics at play, showing how outside forces are ready to take advantage of any opportunity to make money. Arguably as remarkable as the story itself is the film’s sound design (as the title might suggest). While the images on screen can sometimes unveil at a glacial place, the film never stops speaking to us through its emphatic sound design, with offscreen noises indicating the multiple narrative layers building toward a crescendo.

Mendonça is also credited as the film’s sound designer, as he has been on his subsequent features Aquarius (2016) and Bacurau (2019), which both played at the Cannes Film Festival. He talked to Galerie about how he approaches this primal sensory element, and how he deploys sound to stimulate audiences and drive storytelling.

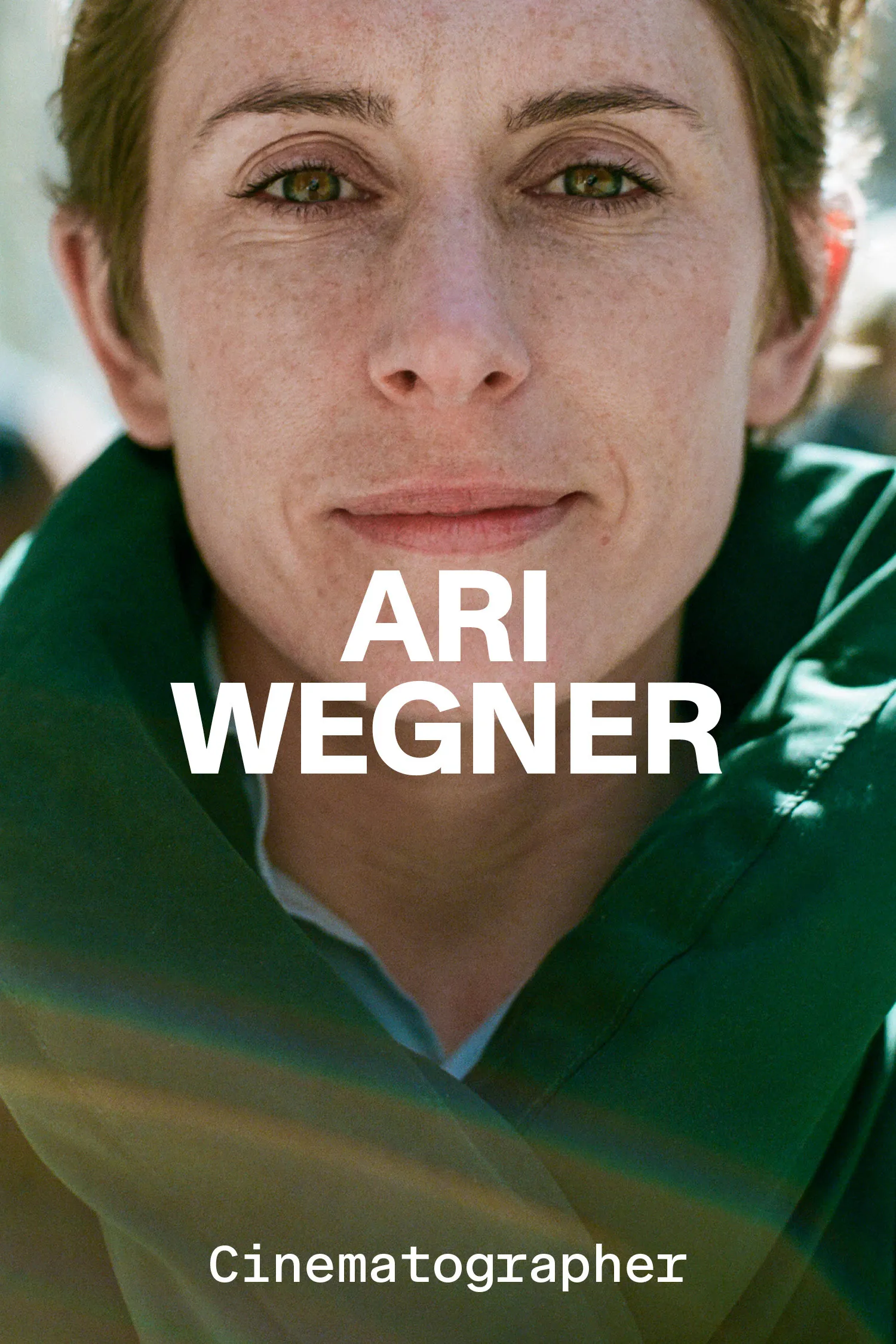

Gustavo Jahn and Waldemar Solha in Neighboring Sounds

In Neighboring Sounds, even the title speaks of aural power in our lives. How do you think sound interacts with visuals in creating a film?

I would never talk about it in terms of degrees of power. Sound and pictures come from completely different worlds. Together they are powerful, but they also work independently. For example, I don’t like the little headphones they give you on flights, so I often watch films on planes without listening to the sound. That’s one experience. However, I also love driving and listening to a film. With films, I believe that bad sound is when sound is added just to avoid silence. For example, it’s lame when someone walks into a room and you hear footsteps. But maybe after you hear footsteps, you hear someone drinking coffee at a higher sound than it should be—that becomes a little more interesting. I think you can play Neighboring Sounds without watching the image.

When you were driving and listening to films, how did you get the audio?

I never took a tape recorder to the cinema. I would tape-record at home from the television in the days before VCR. I would record the sound, music and action scenes and listen to films repeatedly.

Do you remember what films you were recording and listening to?

I remember recording scenes from Raiders of the Lost Ark, which must have been from a VHS tape, and one that sticks in the memory is when he is fighting the giant under the wing of the Nazi plane. Also, a Brazilian film by Hector Babenco called Lúcio Flávio had a dialogue scene in the first 15 minutes between a dirty cop and a guy who doesn’t want to snitch on the main character. I thought the dialogue was great, even though the recording I had was missing some words because the television channel would bleep the swearing out. I found listening to the audio so exciting that I could never go to sleep.

You spoke about making the sound design more interesting by resisting convention and thwarting our expectations. In Neighboring Sounds, there are examples of this throughout. What’s the impact of elevated sound?

Filmmaking is often dominated by technical processes, and that’s kind of problematic. For example, car chases are the result of procedures. So if you really want to do something different, you have to work out ways to film it differently. The problem with car chases is that the rules come from safety protocols, and that makes every car chase look the same, from where the camera is positioned to how the cars flip. Unless, of course, you see an Australian film where none of those procedures were used, where the stunts are kind of outlawed and suicidal, and then you get something like Mad Max. The same is true with sound. You can go by the book or decide to play with the sound in unique ways. Often in Brazilian films people use sounds from sound libraries, which are American sound libraries because we watch a lot of American films in Brazil. Consequently, someone turns the engine in a Brazilian film, but the traffic outside sounds like Oklahoma. I believe in having our own sounds, which should be used in a different way than the technical procedures have established, so your film will sound very specific. If you just follow the rules, it will sound generic.

So is there a Brazilian sound library you use?

No. For the most part we record the sound on set. It’s essential to do the atmospheric sound on set, and we do the Foley ourselves.

And for the car crash at the start of Neighboring Sounds, how did you make it different?

That’s a funny story, because we used a professional stunt driver and he was hoping to flip the car, which would then explode. But instead we had a very uneventful little crash, something that would happen at 9am. He was really frustrated because his procedure was to make something spectacular, and we hear the crash more than we see it.

Gustavo Jahn and Irma Brown in Neighboring Sounds

You use many sound transitions in Neighboring Sounds when moving from one scene to the next. What does that add to an edit?

The sound makes everything hang together in a film, almost like the seams of clothing. Often I watch films which keep resetting the sound every ten minutes or so to keep the audience interested, like there is a fade out and complete silence, and then the sound restarts with a different emphasis. I like my films to be in a continuous mood, with the sound taking you forward. Even if some people consider the films slow, there is always a tapestry of sound present, and the dissolves take you there. Sometimes you can use dramatic sounds to punctuate, almost like a full stop or a paragraph. Neighboring Sounds begins with music, and then we move over to the kids on roller skates, and then to the kids in the playground area, and everything is just a series of sounds that come in, and then the next one comes, and the audience keeps going with the sounds in the film. The kids are kissing and the cars crash, and as soon as the cars crash it’s nighttime, and now dogs are barking, as opposed to after the car crash the sound fading out, or there being complete silence signifying the end of part one. We would have lost momentum if we did this, which is the standard way of doing sound.

“THE SOUND MAKES

EVERYTHING HANG TOGETHER

IN A FILM, ALMOST LIKE SEAMS

OF CLOTHING.”

In both Aquarius and Neighboring Sounds, it is diegetic when you use famous songs. Is there a reason for that?

Well, I don’t have a problem using nondiegetic songs, as evidenced by the music in my other film, Bacurau. But it’s true, I love—like in our lives when we sit down to actually listen to a song and turn it up loud—that look of pleasure on the listeners’ faces. But you have to choose the right song when we have characters do that. We see that in Aquarius with the Queen songs “Another One Bites the Dust” and “Fat Bottomed Girls,” and the use of “Crazy Thing Called Love” in Neighboring Sounds.

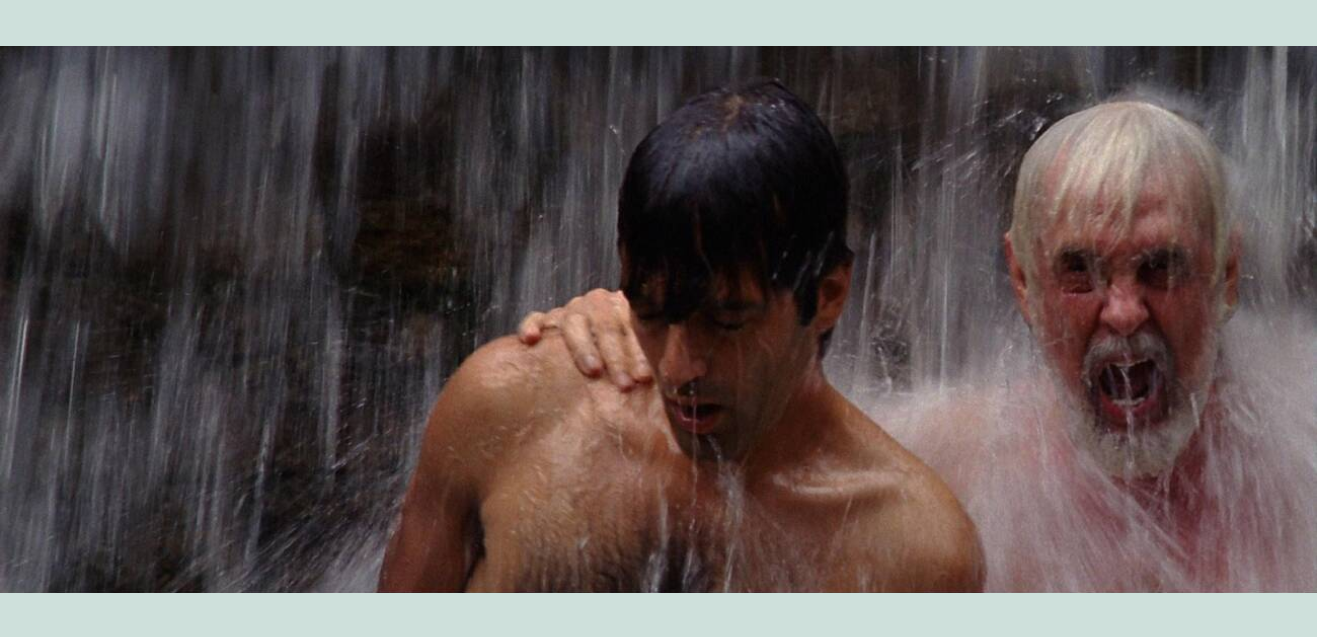

Bacurau, dir. Kleber Mendonça Filho, 2019

In Neighboring Sounds, sound also works as a stimulant and part of the narrative, most notably with the thunderous washing machine, recalling a vibrator, to which the character masturbates.

I like juicy sounds that sound good in cinematic terms and mean something to the film. The washing machine reaches levels of absurdity because it’s so extreme the way the sound takes over the film and the shaking and the power of that machine. That’s probably how she feels when she’s enjoying the stimulation as she masturbates. It’s almost like being infatuated or being in love with someone and it becomes hyperreal. I feel it would have been a missed opportunity if I shot her from seven feet with a normal sound level and then you clinically see someone masturbating, which would have been another way of doing it. It wouldn’t be wrong, but with the Sergio Leone type of super close-ups and the super sound I think it’s an interesting sequence and very much about her.

What would you say your influences were in sound design?

I started paying attention to sound when I began to watch a few American filmmakers who came from the Hollywood school of sound. By that I mean they are technically amazing and very hyperrealistic, but then they would leave the road of normal procedures and go into something a little more expressionistic. For example, when I saw Wild at Heart, David Lynch’s film, I saw it in a very good cinema in Brazil, and I said to my companion, “This sound is a different sound—it’s not just a normal American film sound.” Sure enough, I think in his next film I saw, that was the first time I saw Lynch’s name as a sound designer. Again, when I saw Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, not in the cinema but on VHS, I also thought the film sounded very unusual. The other time this happened was with Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee’s film. I looked at the credits and saw Skip Lievsay was the sound designer and I knew that name from the Coen brothers’ Raising Arizona, which also had a very interesting soundscape. So it was through these filmmakers that I built this idea of how sound should be used in my film. Lost Highway also has a very interesting soundtrack. I remember the Rammstein music coming at an unbelievable volume. Those atmospheres in Lynch movies and those hyper sounds were certainly inspiring for me, especially when I was in my twenties. The funny thing is that because they inspired so many people, listening to them today it sounds like a cliché that they themselves created.

From left: Wild at Heart, dir. David Lynch, 1990; Do the Right Thing, dir. Spike Lee, 1989; Lost Highway, dir. David Lynch, 1997

So was it Lynch who inspired you to claim the sound designer credit for yourself?

Well, when the sound designer credit began to appear, it was very late ’70s, with Walter Murch’s credit on Apocalypse Now. But I really liked the idea that the director would work on the sound. Normally you work with people you like, and then the sound designer does the sound. Today with technology you can record great sound and take it to the edit; you can put a wonderful microphone on the iPhone and record great, great sound. You go to the edit, AirDrop, and it’s immediately in the computer. The editor drags it to the timelines and whoa, that sounds good.