Face Values: Philippe Rousselot

By Yonca Talu

Dangerous Liaisons, dir. Stephen Frears, 1988

FACE VALUES

Yonca Talu

An epistolary conversation on craft with the vaunted cinematographer of Dangerous Liaisons, Diva and Queen Margot

January 5, 2024

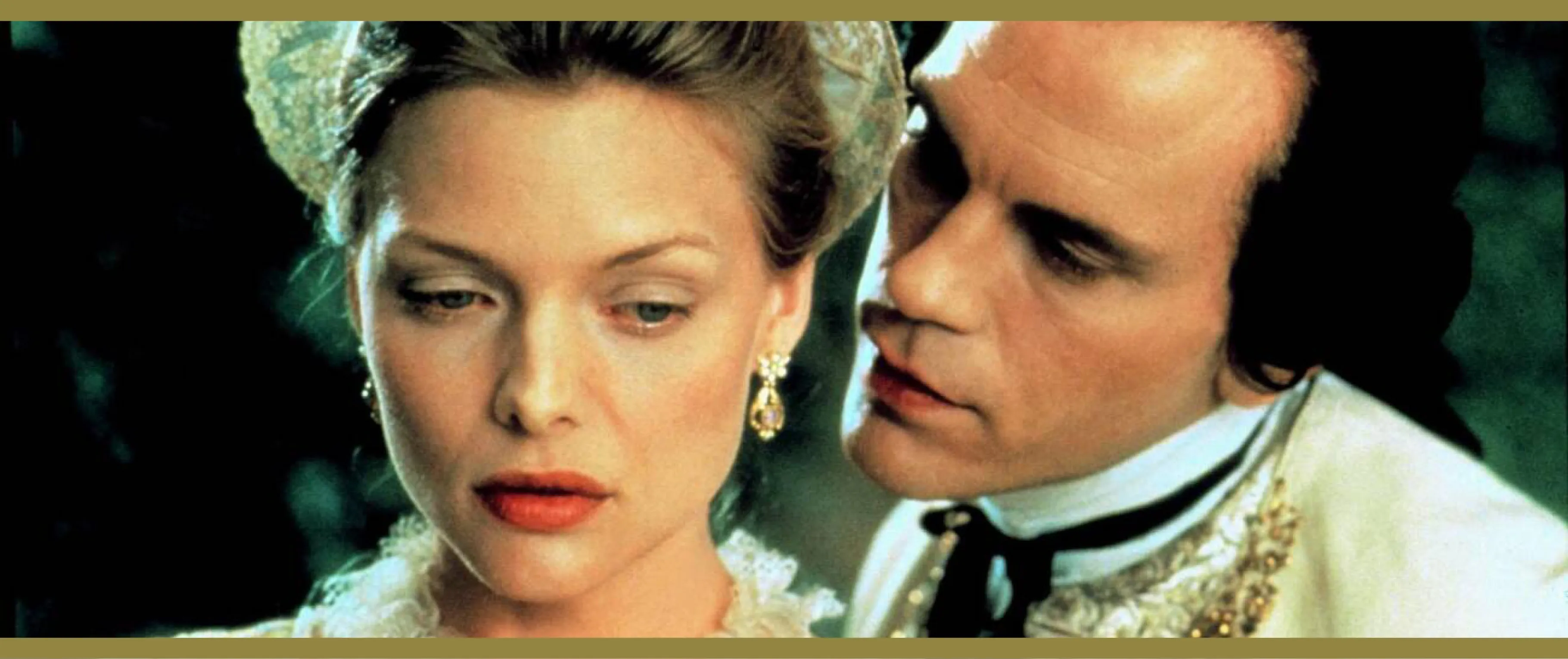

One of the most gifted and prolific cinematographers of our time, Philippe Rousselot has made his mark both in Hollywood and his native France through his collaborations with directors as varied as Jean-Jacques Beineix, John Boorman, Stephen Frears, Robert Redford, Neil Jordan, Patrice Chéreau, Milos Forman and Tim Burton, among others. A highlight of Rousselot’s five-decade-spanning filmography, Frears’s sensuous and chilling period drama Dangerous Liaisons (1988) offers a master class in candle-driven lighting and fluid, intimate camerawork. Adapted by Christopher Hampton from his play based on Choderlos de Laclos’s iconic 1782 novel Les liaisons dangereuses, the film follows two decadent Parisian aristocrats, ex-lovers Marquise de Merteuil (Glenn Close) and Vicomte de Valmont (John Malkovich), as they lure a young ingenue and a pious married woman (played by Uma Thurman and Michelle Pfeiffer, respectively) into a web of sex, corruption and revenge—a risky scheme that also leads to the conspiring duo’s own downfall.

In tribute to the epistolary form of the film’s source novel by Laclos, I corresponded with the Academy Award–winning director of photography about his experience shooting Dangerous Liaisons and how he’s developed his approach since the late ’60s, when he started out as an assistant to venerable cinematographer Néstor Almendros. —Yonca Talu

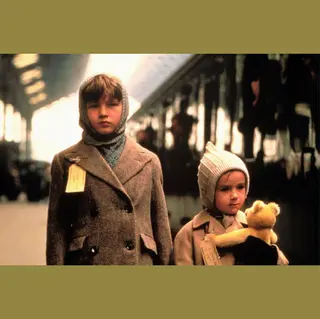

From left: Keanu Reeves and Uma Thurman in Dangerous Liaisons; Interview with the Vampire, dir. Neil Jordan, 1994

Dear Philippe,

I hope this letter finds you well. I recently had the pleasure of coming across your remarkable book, La Sagesse du Chef opérateur [The Cinematographer’s Wisdom; 2013]. In a late chapter of the book, which reads like a philosophical essay, you mull over your fascination with the human face and its mystery. For example, you write, ‘‘One should be amazed at what each face has to offer, both a total strangeness (the Other is always a complete stranger) and its opposite, a familiar presence.’’ I feel like this passage resonates powerfully with your work on Stephen Frears’s Dangerous Liaisons, which is replete with close-ups of its Machiavellian protagonists, 18th-century libertines Marquise de Merteuil and Vicomte de Valmont. Throughout the film, the camera penetrates the intimacy of Merteuil and Valmont and probes their faces from every angle, capturing their slightest expressions and gestures. But, however exhaustive these close-ups may seem, there’s something about them that defies emotional identification. It’s as if the camera comes up against the impossibility of ever really knowing what Merteuil and Valmont are thinking and feeling, of piercing their masks. Stephen Frears has said in interviews that he had initially envisioned Dangerous Liaisons as a film that would play out in long master shots. How did you two end up gravitating toward a mise-en-scène driven by close-ups? From there, how did you go about framing and lighting the sphinxlike faces of Glenn Close’s Merteuil and John Malkovich’s Valmont?

Yonca

Thérèse, dir. Alain Cavalier, 1986

Dear Yonca,

Thank you for reading La Sagesse du Chef opérateur and your kind comments. Trying to answer your questions, I can’t help but see the gap between the thoughts I’m having now and the ones I may have had when we were shooting Dangerous Liaisons. I wonder how much I might, albeit unconsciously, rewrite history; hence the caveat. I could retrospectively present our work as based on clear decisions and precise concepts, but I know this was not the case—it never is. I would think that day-to-day attention to what the actors were doing was our only strategy.

I was unfortunately in the hospital for weeks before the shoot, which reduced my prep time to almost nothing and allowed me very little time with Stephen. On our first meeting, he told me that he had no interest in the period itself. He was concerned that the gilded, bright 18th-century interiors and all the “exotic” aspects of life back then would distract from the drama. Later, when we were already well into production, he remarked that in order to show that the characters were lying to each other and themselves, we needed tight close-ups on them. This was a conclusion he reached after seeing the dailies, and it’s all I remember from our discussions on the matter of close-ups. I don’t remember Stephen mentioning that he wanted to stage the action in long master shots, but it’s often the case that one starts with ideas that fail on the first days of shooting and point one firmly in the opposite direction.

I have this odd image of the Dangerous Liaisons shoot. The set was like a pool table, while the dialogues were like balls following all kinds of trajectories, hitting each other and changing directions in unpredictable ways. In the middle of it all was the camera, which followed one ball after another while avoiding being hit. It was constantly on the move and tried to be as close as possible to the action when an impact occurred. I like your description “It’s as if the camera comes up against the impossibility of ever really knowing what Merteuil and Valmont are thinking and feeling, of piercing their masks.” I agree, especially because I don’t believe there’s any magic to the camera. It’s only able to show what the actors offer, and in this respect, ours did an excellent job at hiding their inner thoughts. The only thing the camera could do was to insist, as you noticed, against formidable resistance. There were a few exceptions [i.e., vulnerable moments], like when Merteuil realizes that Valmont has fallen in love with Madame de Tourvel, played by Michelle Pfeiffer. But otherwise the camera was just another victim in this cat-and-mouse game—always a second too late or an inch too far.

As per framing and lighting faces, there are no rules. As a director of photography, you circle the actor like a cat circles its prey, looking for the best angle to attack, until you find yourself spellbound by what you think is the essence of their face. On a more prosaic note, we had a fantastic makeup artist, Jean-Luc Russier, who gave the actors porcelain-white skin tones with a hint of coldness—the opposite of yellow-orange skin tones favored in Hollywood. Cold skin tones also take much better the warm light of candles, which we used a lot on Dangerous Liaisons.

Philippe

From left: Judith, Giorgione, 1504; A River Runs Through It, dir. Robert Redford, 1992

Dear Philippe,

Thank you for painting such a vivid picture of what it felt like to shoot Dangerous Liaisons. I’d like to pick up on your comment about the actors’ porcelain-white skin tones and dig deeper into how you crafted the film’s lighting. You mentioned that Stephen Frears wasn’t interested in making a period movie per se and wanted to focus on the drama instead. In fact, a significant aspect of your cinematography in Dangerous Liaisons is the use of soft lighting and shallow focus to make the characters stand out from their 18th-century environment. Sometimes you heighten this effect to the point of plunging the background into near-total darkness, creating stripped-down, almost abstract images in which faces take the central stage. Before Dangerous Liaisons, you had experimented with a similar aesthetic on Alain Cavalier’s Thérèse (1986), a film about 19th-century Carmelite nun Thérèse of Lisieux shot entirely against a gray studio backdrop and consisting mostly of close-ups. Is there a continuity between how you approached Thérèse and Dangerous Liaisons? Did you employ your trademark lighting technique of China balls on both of these films?

Another entry in your filmography that bears similarities to Dangerous Liaisons is Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire (1994). There’s an evocative quote about that film in your book, which I think also applies to Dangerous Liaisons: “The light is a wound and the shadow is what heals it.” Like the protagonists of Interview with the Vampire, Merteuil and Valmont in Dangerous Liaisons are creatures of the night. They put on an act during the day and unleash their true, debauched selves at night, healing, as it were, in the shadows of your chiaroscuro lighting.

Yonca

Days of Heaven, dir. Terrence Malick, 1978

Dear Yonca,

You’re right: Merteuil and Valmont are creatures of the night. In that regard, I wanted the film’s night scenes to have soft lighting and low contrast and its day scenes to have as sharp a contrast as possible, which went against the established doxa of using contrast for nights and flatter lighting for days. On the other hand, it wasn’t a formal decision to use shallow focus, in that there were no alternatives. We shot on a 250 ASA film stock, which is very slow compared with today’s digital cameras. Filming so many candlelit scenes also required us to keep all the lights at a low level for the candles not to look dead. Add to that the use of long lenses (100 and 150 mm) for close-ups, and you get shallow focus. It was a nightmare for our focus puller, Myriam Touzé, but it’s true that it helped the background disappear. It also created a flatness of perspective and a sense of visual uniformity that, in the vein of Baroque portraits, allowed for more intimacy with the characters.

Going back to the subject of lighting faces, I’ll try to be more precise. There’s indeed some continuity between my work on Thérèse, Dangerous Liaisons and Interview with the Vampire, as well as on films like Patrice Chéreau’s Queen Margot (1994) and Stephen Frears’s Mary Reilly (1996). From the early ’70s until I moved to the U.S. in the ’90s, I worked on many fashion and cosmetics commercials with the wonderful French photographer Sarah Moon. I learned a lot from Sarah, who has so much dedication to the beauty of her subjects’ faces. Even more so, I should say, respect for them, because I don’t believe that a photographer or cinematographer can ever make someone beautiful. On the contrary, they can easily miss, or even destroy, the beauty of someone’s face.

Lighting a face is mostly a cleaning operation. It’s about getting rid of all the accidents that come from different light sources on the set and outside—all those useless, distracting shadows and highlights that mar the tone and shape of a face, like ripples on the surface of a lake. I like to isolate the actors from their environment by using two systems: one for the set and another for faces. Looking at a face up close, we don’t pay attention to or register the background, but the camera does. It does not differentiate between the two, which is why I usually darken the background in closer shots.

That’s where the ‘‘famous’’ China balls come in. After years of using some more cumbersome contraptions, I started using China balls on John Boorman’s Hope and Glory (1987), though I don’t use them anymore. The principle of a China ball is that when you place it three feet away from an actor’s face, it produces the same soft light as a 12-by-12-foot bounce surface 20 feet away. It’s the angle that determines the softness/hardness of the light, not the contraption itself, and in both cases the light comes from the same angle. The difference is that with a China ball close to the actor, the background receives less light, if any. With the bounce far away and necessarily behind the camera, the background receives about the same amount of light as the actor. An example of double standard would be Giorgione’s 1504 painting Judith. Judith has her own light! The tree and landscape behind her pertain to a different atmosphere and light. (What’s good for Giorgione is good enough for me.)

I never expected the use of China balls to become so popular among actors and actresses, but I realized that they were very pleased to have their own light. Of course, I didn’t invent anything. Think of Marlene Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg’s films from the ’30s: She always has her own light, regardless of the environment. In short, the China ball proved to be a convenient tool for achieving the chiaroscuro you talked about in Dangerous Liaisons.

Philippe

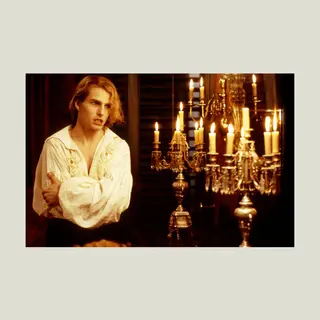

From left: Hope and Glory, dir. John Boorman, 1987; Tom Cruise in Interview with the Vampire

Dear Philippe,

What an insightful demonstration of your China-ball technique! I love your suggestion that its roots reach back to the Giorgione painting Judith and Josef von Sternberg’s films with Marlene Dietrich. You also touched on your collaboration with photographer Sarah Moon as a formative period in your career in terms of finding your approach to lighting faces. On that note I want to bring up another great artist you collaborated with in the late ’60s and early ’70s, your mentor, cinematographer Néstor Almendros. He makes a brief appearance in your book by way of a quote: ‘‘My favorite landscape is the face, which is where I find the most fascinating valleys and mountains, the clearest lakes, the densest forests.’’ Almendros’s words here are doubly meaningful. He was a master not only at filming faces but also at wielding natural light, as in one of his most famous achievements: the stunning and daring magic-hour cinematography in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978). You were Almendros’s camera assistant on Éric Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s (1969), Claire’s Knee (1970) and Love in the Afternoon (1972). What are your memories of working alongside him, and how much did he influence you as a cinematographer? When you shot Robert Redford’s A River Runs Through It (1992), the majority of which takes place outdoors, around Montana’s scenic Blackfoot River, were you inspired by Almendros’s committed use of natural sunlight?

Yonca

Glenn Close in Dangerous Liaisons

Dear Yonca,

Your questions always hint at correct answers, as if you were reading my mind. Yes! Néstor had a great influence on me, and I’m forever grateful to him. He was indeed a master of natural light, which he used in a way that had rarely been used before. But what is natural light, anyway? On A River Runs Through It, most exterior locations were too remote to bring a generator and heavy equipment, so the light was, by definition, natural. The rules for each scene, even for each shot, consisted of choosing specific moments in which the sun was at the right place. One could say that natural light is what seems natural to an audience, but this is something that has constantly evolved since the early days of cinema. A modern audience would not buy the dark blue night scenes of Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959), which seemed so wonderful back then. You mentioned Néstor’s work on Days of Heaven. That film was shot entirely at magic hour—the short time between sundown and darkness—which, in a way, is completely unnatural! But it’s also true that Néstor didn’t use any artificial lights on Days of Heaven.

For me, what mattered most was Néstor’s intellectual approach. He started his career in documentary filmmaking—a great school for young DPs—in the ’50s, in Cuba. As far as I know, he was mostly self-taught in cinematography. His approach was not founded on any established practices. It came from logic and his observations and analysis of light situations in the real world. (Come to think of it, his invention of bounce light was a genius idea, but it was also just common sense!) Néstor did not carry the weight of tradition and had no desire to resemble his predecessors. He had no interest in the tight hierarchy imposed on film crews, which made his road to the top so long and painful. He had great taste and an aesthetic all his own. His work on set was transparent and immediately understandable, and he was always happy to talk about it and pass on his knowledge. In short, what I learned from Néstor is freedom—freedom from established doctrines. Each film starts with a blank slate. It’s a confrontation with a new reality, from which one derives a brand-new set of rules. Rules vary during the shoot and are sometimes dictated by reality itself. One must always be prepared to confront chaos. As a joke, my motto at the beginning of every production comes from Dante’s Inferno: ‘‘Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate’’ [i.e., ‘‘All hope abandon, ye who enter here’’].

Philippe

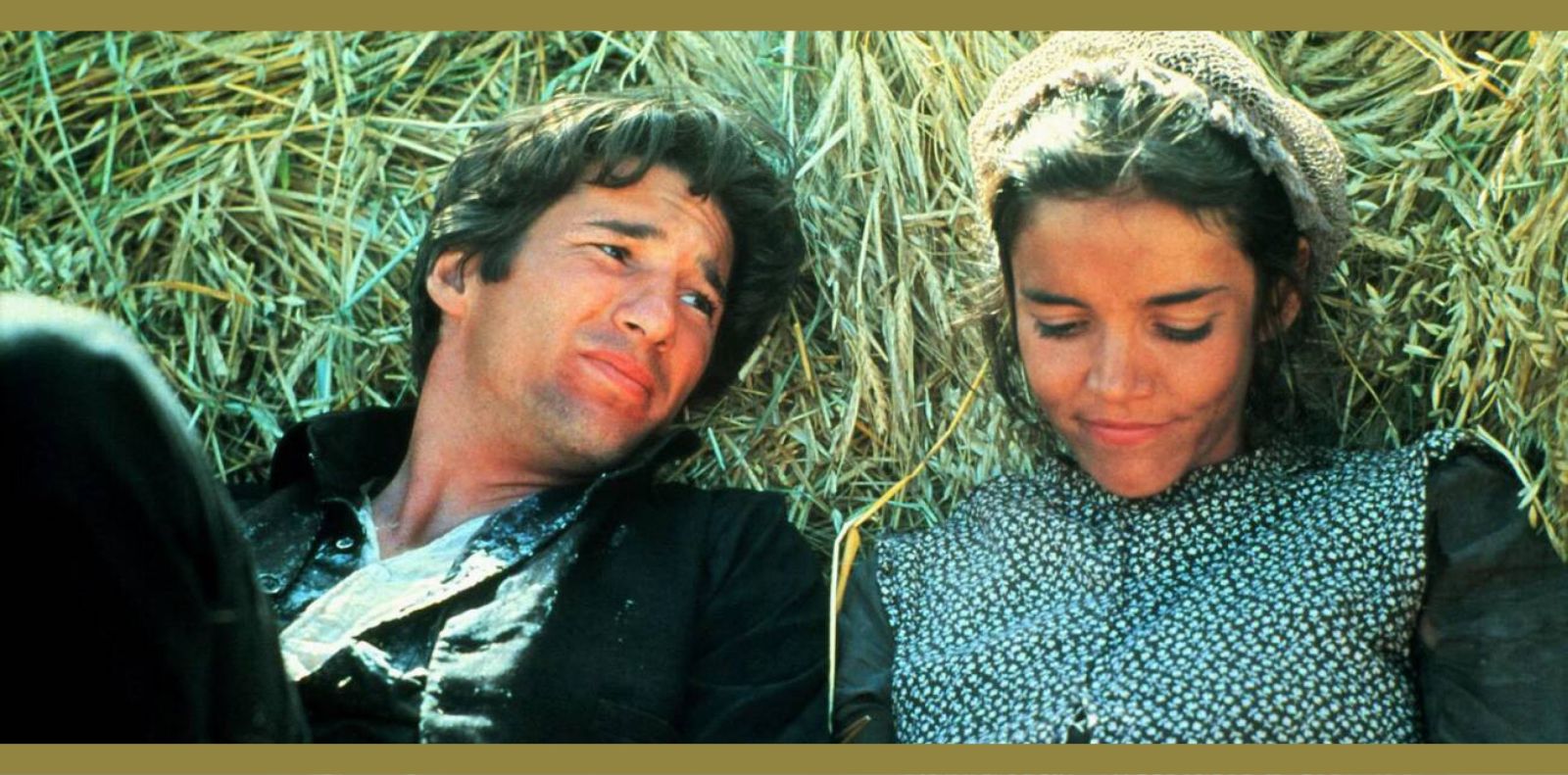

Richard Gere and Brooke Adams in Days of Heaven