Ozu’s Family Values

By Joshua Sanchez

![]()

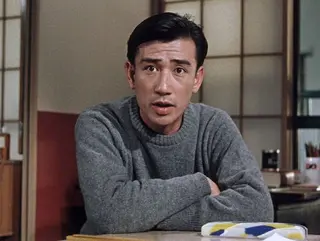

Good Morning, dir. Yasujirō Ozu, 1959

Family Values

Yasujirō Ozu’s Good Morning is a deceptively breezy treatise on the quiet drama of the suburbs

By Joshua Sanchez

July 5, 2023

Director Yasujirō Ozu is buried at Engaku-ji, a beautiful, ancient Zen Buddhist temple complex in Kamakura, Japan, about an hour's drive south of Tokyo. Often flanked by gifts of incense, sake and cigarettes left by loyal film fans, his grave is an imposing black marble slab etched with the Chinese character for mu.

Loosely translated, mu means “nothingness” but, in accordance with Zen philosophy, a nothing that infers everything. A person inhabiting mu displays a high attention to the comings and goings of life and its impermanence. Any viewer of Ozu’s vast filmography—a body of work that spans 54 films from 1927 to 1962, a year before his death—can instinctively understand why his work possesses the concept of mu. He was a monastically devoted filmmaker who proved a keen observer of postwar family life in Japan. He never married or had children. By his own admission, cinema was his life. Practically each of his films can be read as an incisive meditation on the Japanese family. Although some critics have found his films repetitive, such a complaint misses the finer point. As Ozu once put it, “Although it may seem the same to other people, each thing I produce is a new experience and I always make each work from a new interest. It’s like a painter who always paints the same rose.”

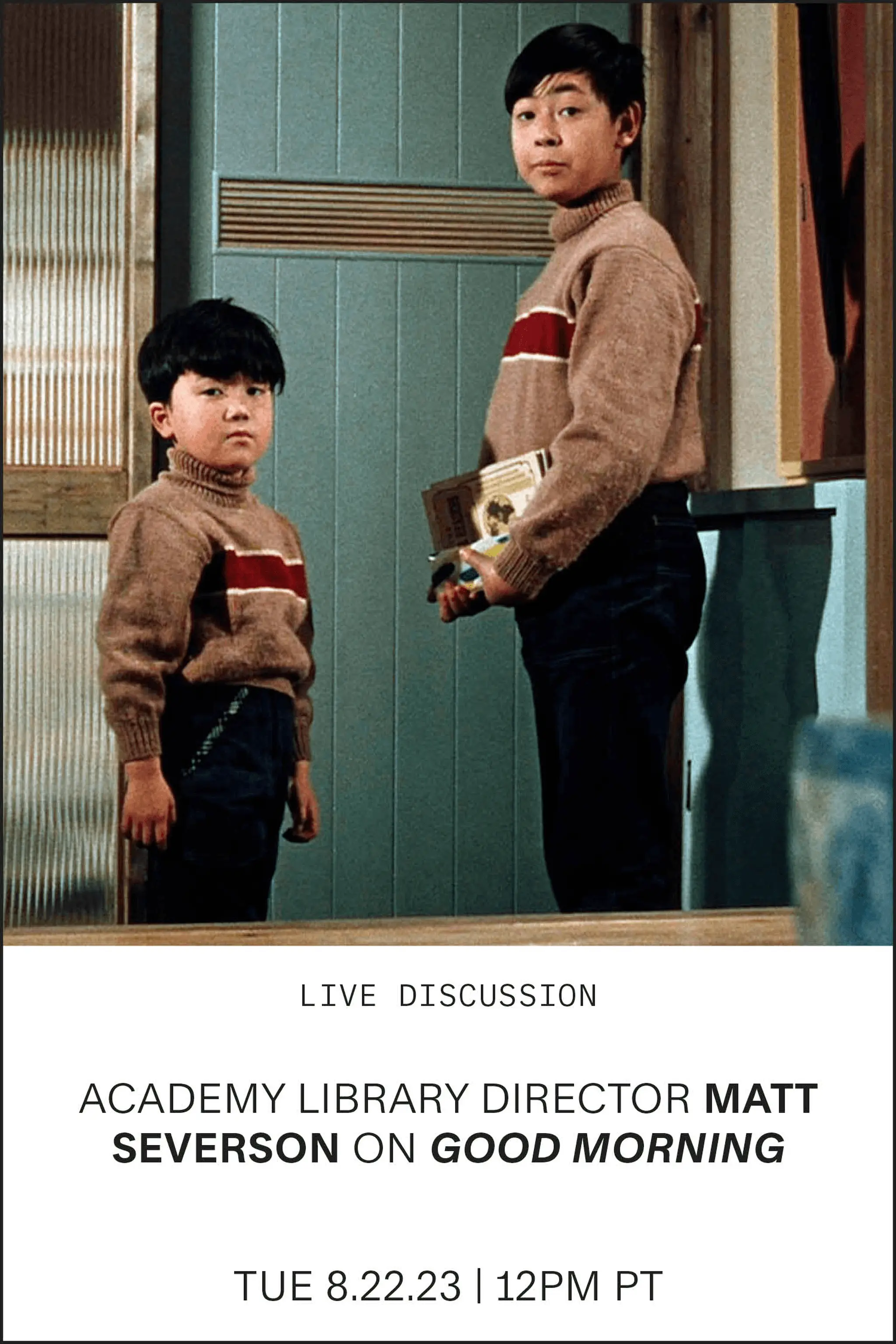

From left: Good Morning, 1959; Late Spring, 1949; I Was Born, But..., 1932

Over his 35-year career as a film director, Ozu rarely strayed from using a stationary camera mounted as low to the ground as possible with a 50mm lens. This lens duplicates a depth of field similar to that of human vision. Although Ozu never explicitly stated the reason for shooting the majority of his films this way, scholars generally agree that he sought to give the audience the presiding view in a traditional Japanese house—on a tatami mat directly on the floor. Through this authentic frame, watching Ozu’s films often feels like experiencing the goings-on of his characters as intimately as if we were sitting down to dinner with them.

If you know Ozu only from the melancholy atmosphere of his better-known dramas such as Late Spring (1949) and Tokyo Story (1953), it may come as a surprise to discover that he also had a penchant for comedy. Although often wrongly considered one of the director’s lesser late-period works, his color film Good Morning (1959) shows his deftness at using humor to explore the deep inner workings of the Japanese family—in this film’s case, the attempts across generations and household divides to find a stable bridge of communication at home and among neighbors.

Affectionately referred to as the “fart film” by fans, Good Morning begins with a playful scatalogical game between schoolboys. Minoru, his younger brother, Isamu, and their friends Kôzô and Zenichi press on each other’s foreheads to trigger a fart, which in the film’s universe sounds more like a flute. If one of the boys can’t fart (Kôzô shits his pants trying), he is shamed. Good Morning is, in fact, a loose reconstruction of Ozu’s 1932 silent comedy I Was Born, But…. In the earlier film, two young brothers whose family has relocated to a new neighborhood outside of Tokyo find themselves relentlessly bullied by schoolmates, one of whom turns out to be the son of their father’s boss. In the brothers’ eyes, their father is an important man, so when they discover the subservient role he plays to his boss, the two boys retaliate by going on a hunger strike. Ozu winkingly recasts the injustice in Good Morning’s postwar suburban life as the parents' refusal to buy their sons a television set. Instead of a hunger strike, the brothers retaliate with a vow of silence.

Good Morning, dir. Yasujirō Ozu, 1959

Silence plays a central role, not only in the absolute shutdown of verbal communication from the two boys, but in the silence between members of the larger suburban community. Early on, Isamu and Minoru’s aggressive whining about not having a television set infuriates their mother, Tamiko, who scolds them for being unreasonable. After the boys take their vow, Tamiko worries and wants their voices back. In a subplot, Tamiko becomes embroiled in a comic scandal regarding dues for a neighborhood women’s organization; she’s paid them, but the funds have gone missing. The women make catty accusations to one another but never come together to confront the problem directly. In both cases, silence is the way this community functions, a passive protest that builds and builds. It’s possible that Ozu explored this aspect because it reflected the mores of Japanese society, which values a very particular etiquette in all transactions. But as is typical of him, he presents the social conundrums without ever judging them. In a sense, silence even operates to keep society running.

The boys’ family home serves as the primary location of the film. Its hallway often functions as a tunnel of miscommunication, with characters shouting at each other from end to end. After the boys finally get their television, we see it in a box in the middle of the hallway. The boys are in their room wearing matching outfits, jumping for joy and play-fighting in celebration of their victory. Ironically, their father, Keitarô, screams, “If you’re going to be so noisy, I’ll return it!” Ozu deliberately shoots the hallway in his signature low angle, which makes the vertical walls seem endless even when, in reality, the space is rather small. That distortion only further emphasizes the physical and psychological distance between family members.

In another example of silence and distance, Kikue, the neighborhood’s hilarious busybody, barges into the house to confront Tamiko about the missing dues. Tamiko bows politely to Kikue despite the withering look on Kikue’s face. In a tense but polite exchange, we see the two women conceal what they’d like to say to each other. The struggle to keep silent emphasizes the true point of the visit. In Kikue’s face we can see the charge, and in Tamiko’s we sense the response: “How dare you accuse me of stealing the dues!” This exchange plays without a word, as the unspoken code of Japanese manners keeps the breach lurking beneath the surface. Behind them a door is left open so that we can see into the house across the alley, connecting the characters’ conflicts by connecting their homes in the frame. The result is claustrophobic.

In many ways, Good Morning is about the elusiveness of genuine communication—how even everyday pleasantries, often taken for granted, can replace honest opinions or insights. “Good morning” is uttered several times, often miscommunicated for comic effect. But there’s value in the greeting too. The film explores just how important these seemingly benign non-responses can be to the functioning of a community. When first Minoru and then Isamu snub Kikue after she enthusiastically greets each of them, she falsely interprets their reaction as a directive from their mother to intentionally snub her, when in reality the boys are still on their vow of silence. A simple refusal to say good morning seems innocuous, but communicates a much larger divide. Toward the end of the film, Isamu and Minoru’s aunt Setsuko waits on a train platform. The boys’ handsome English tutor, Heiichirô, appears and the romantic tension between them is palpable. Here, their manners get the better of them and they talk about the weather. “Good morning,” Heiichirô says. “That cloud’s got an interesting shape.” Their feelings for each other can be read in their subtle glances, while their spoken attraction is transferred to the clouds. Even love doesn’t conquer etiquette.

Of Ozu’s 54 films, only 6 were shot in color—the last works that he made. Good Morning is his second color film, and we can intuit how excited he must have been to play with this novel dimension, particularly its possibilities to enhance his symbolism. The colors in the film are vivid, almost otherworldly. A green tea kettle that belongs to the family holds particular significance. We see this kettle several times around the house—an incidental yet beautiful utilitarian object. As the brothers’ vow of silence continues and their isolation from the family increases, they kidnap the green kettle and retreat to a levee where they eat a somber and lonely lunch, the kettle a symbol of a home from which they feel alienated. The most poignant symbol, however, might be the one that opens and closes Good Morning: a shot of neighborhood clotheslines. In the first scene the clotheslines sit in the background with electrical towers looming in the foreground. The final shot gives the reverse impression, with clotheslines in the foreground and a tower in the distance. It’s a symbol that could speak about rapid modernization or larger social webs, but it could also be read merely as Ozu’s love of ordinary objects existing on the periphery of ordinary lives. Very mu indeed.