Final Cut Pro

By Andrew Bird

Girl with a Suitcase, dir. Valerio Zurlini, 1961

FINAL CUT PRO

A film editor’s appreciation of Mario Serandrei, a legend of the craft with a humane touch

By Andrew Bird

December 21, 2023

Having worked as an editor of both narrative and documentary features for over 30 years, I always pay great attention to the editing when watching films. Where others make mental note of great directors and acting talents, it’s the names of editors that I store away for future viewing reference.

One film that originally inspired me to embark upon a career in film editing was Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers (1960), first seen when I was beginning to reflect upon the impact that cutting has on the emotions felt by every single individual in the audience. The editor of Rocco was Mario Serandrei, whose name I put to memory.

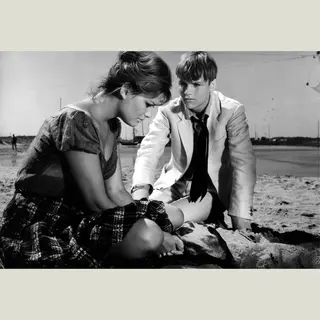

Claudia Cardinale in Girl with a Suitcase

Born in Naples in 1907, Serandrei died in Rome in 1966 and is credited as editor of a mind-blowing 264 films. To put that into perspective, I manage on average one and a half films a year. How Serandrei achieved such an incredible number is beyond me, but his credits include such seminal works as The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966), Salvatore Giuliano (Francesco Rosi, 1962) and the Oscar-nominated documentary The Grand Olympics (Romolo Marcellini, 1961); Visconti’s La terra trema (1948), Senso (1954) and The Leopard (1963); and a number of horror films by the master of the genre, Mario Bava. In addition, Serandrei has been credited as the person who coined the term neorealism, now in standard use to describe an entire school of Italian cinema from the 1940s and ’50s.

Serandrei’s mastery of his craft can be seen in Valerio Zurlini’s 1961 classic Girl with a Suitcase (La ragazza con la valigia), the story of a young singer, Aida (Claudia Cardinale), who is unceremoniously dumped when Marcello, her wealthy lover, takes advantage of her brief absence to remove her suitcase from the boot of his car and drive off. Her pursuit of him takes her to his family’s mansion, where Marcello sends out his younger brother, 16-year-old Lorenzo, to deny his existence. Lorenzo (Jacques Perrin) falls for Aida, but their differences in age and class make it clear from the outset that this love can only cause suffering for the boy.

Claudia Cardinale and Jacques Perrin in Girl with a Suitcase

Editing is storytelling. It determines what is told, the pace of the telling and the perspective from which every narrative element is brought into play. Much of Serandrei’s editing here is in harmony with Tino Santoni’s cinematography, in particular his superb camera movement. A prime example of this synchronization is the scene where Aida runs away from a suitor, Romolo, and throws herself down on the beach. Following her, Romolo also lowers himself onto the sand, and with him goes the camera, which takes up a position in front of the flirtatious couple’s heads in a two-shot. The performances and tension of the scene are so strong that Serandrei lets the scene play out, resisting the temptation to cut to another scene and hasten the tempo of the film. This is true of the editing within many scenes in the film, and Serandrei’s approach is fully in keeping with Zurlini’s masterful mise-en-scène, as the actors move into close-up and away again, opening up the frame into a wider shot, all in a single take.

It is never easy to gauge the full extent of the contribution made by the editor to any finished film. Much of the work that goes on in the editing room remains a mystery to most viewers, including film critics, industry professionals (particularly those who work on set) and producers. Never visible onscreen are the weeks spent poring through the footage, the hundreds of decisions and choices made each working day, the precision with which cuts have been executed. It’s impossible to know from the finished work how many scenes have been omitted entirely or in part, or which of the remaining scenes have been reshuffled within the narrative. These things are part and parcel of any editor’s work; indeed, were they to become visible, the editor would not be doing a good job. Any film with a smooth and flowing narrative is testament to the editor’s craft.

.jpg)

“The precise timing of each cut in coordination with the Verdi aria makes for an emotionally stirring scene without a word spoken.”

Editing is so often also about knowing when not to cut, and one of the most powerful emotional moments in Girl with a Suitcase comes when Lorenzo visits Aida at the hotel in which he has put her up at his father’s expense, only to find her subject to the sexual advances of some older men. Aida is led outside by one of them, and we are left with a shot on Lorenzo’s back as he watches them go. We then see an album spinning on a record player as dance music sets in. Serandrei cuts to a slightly elevated wide shot of Lorenzo sitting in one of two swinging loveseats on an otherwise empty hotel terrace, an image of painful solitude as the music plays on. As a trumpet comes in, we get a wide shot of the reverse angle, showing us what Lorenzo sees: Aida slow-dancing with the man, who steps away from her to fetch a fur stole while she glances over to Lorenzo. Still in the wide, looking slightly up, we watch through Lorenzo’s eyes as the man places the stole around Aida’s neck and draws her into a close embrace. As they begin to move to the music, the visual shifts to a close-up of Lorenzo’s face, his eyes fixed on the scene in front of him. Serandrei lets the scene play out solely on Lorenzo’s face from this point on. For an entire minute and ten seconds, we feel every pained emotion that flickers across the young lover’s visage and imagine, much more vividly than if we were actually seeing it, what is going on between the couple on the dance floor. The editor makes a conscious decision to stay with his protagonist; in not cutting back to what he is seeing, our emotional response is fully focused on what Lorenzo is feeling. This is emotional storytelling at its best.

Serandrei’s virtuosic technique further reveals itself during a scene at Lorenzo’s family villa. The precise timing of each cut in coordination with the Verdi aria makes for an emotionally stirring scene without a word spoken. Lorenzo has taken Aida home and offers her the opportunity to bathe in the black-paneled bathroom upstairs. The scene starts with Aida exiting the bathroom, the camera panning her movement as she calls for Lorenzo. We rest on her, but we don’t see what Lorenzo is up to until after the music begins. Lorenzo, seen from Aida’s perspective, is standing over a record player playing “Celeste Aida” from the Verdi opera. We cut back to Aida upstairs, creasing her brow in bewilderment, then back to her point of view from the landing as Lorenzo laughs with joy at his little joke. Just as the name Aida is sung in the aria, Serandrei cuts back to Aida at the head of the staircase, who, in realization, joins in Lorenzo’s laughter. In time to the music, she wraps a towel around her damp hair. The scene continues back and forth, with more and more playful angles; at no point do we see the two of them in the same frame, nor does any shot define the exact geography of the location. The entire flirtatious exchange is created in the editing.

Stills from Girl with a Suitcase

One element central to the storytelling of a film, particularly one with a linear structure such as this one, is the passing of time. Transitions are key, and Serandrei shows remarkable dexterity with them in Girl with a Suitcase. The shifts from one scene to the next are unusual because they cut from a character, and then we see the same character in another scene without being first made aware that there has been a time jump, which only becomes apparent as the next scene develops. This technique serves multiple purposes: It delivers something unexpected, causing a slight disorientation, though never for long enough for the audience to become emotionally disconnected from the story; it ensures the story stays tight to the protagonists; it makes the passage of time clear without ever having to be explicit about it; and it progresses the narrative in a compelling way. Take, for example, a moment between Lorenzo and his brother, Marcello, in Marcello’s bedroom. The scene ends with Lorenzo standing, holding his brother’s laundry. The next cut shows Lorenzo in profile, sitting at the dining table, with a housekeeper serving food in the back of the frame. Clearly, time has passed. The phone rings and the camera pans screen left with the worker as she goes to answer it, revealing Marcello sitting next to Lorenzo at the table. From his clothing, the lighting and the dinner table setting, it’s apparent that several hours have passed since they were in the bedroom.

A variation on this approach is to cut from a scene focused on one protagonist to a new scene that opens with a different figure—Lorenzo’s aunt, for instance, who answers the phone only to pass the receiver to Lorenzo, who enters the frame as he comes down the stairs. Again, we are visually intrigued by the new character, then swiftly drawn back into the boy’s story while at the same time being made aware that several hours must have transpired since the previous scene. It is a pattern repeated throughout the film, without ever becoming overused or dull. Instead it serves to retain the viewer’s attention without the narrative ever standing still. This, to me, is Serandrei’s greatest achievement in Girl with a Suitcase. Watching it over and over, I find great pleasure in this transition technique and can see myself attempting to utilize it in my own work when the footage I’m cutting permits.

From left: Senso, dir. Luchino Visconti, 1954; two ballroom scenes from The Leopard, dir. Luchino Visconti, 1963; Rocco and His Brothers, dir. Luchino Visconti, 1960; Black Sunday, dir. Mario Bava, 1960