Pulp Fiction's Battle Royale

By Garth Risk Hallberg

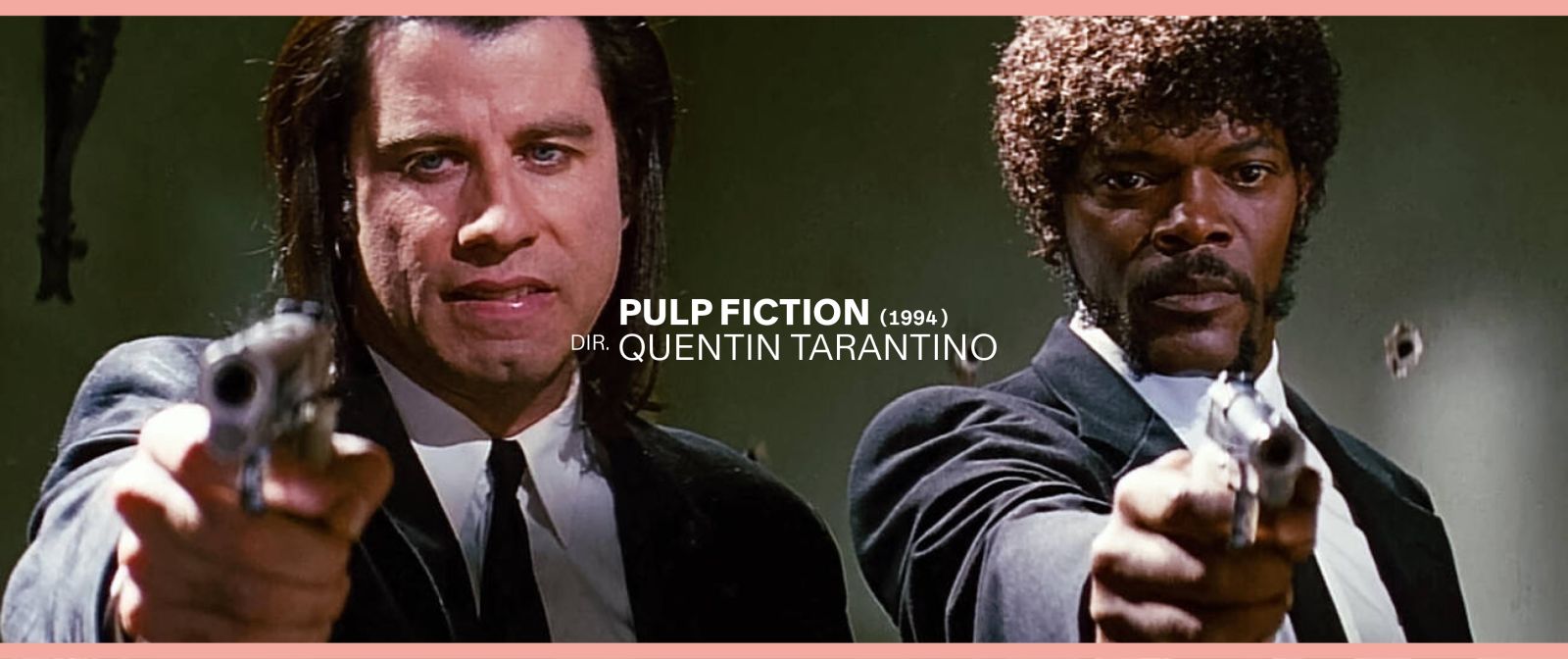

Pulp Fiction, dir. Quentin Tarantino, 1994

Pulp Fiction’s Battle Royale

Aesthetics and ethics face off in Quentin Tarantino’s game-changing 1990s masterwork

By Garth Risk Hallberg

January 31, 2025

Can it be right that it was my father who took me to see Pulp Fiction in the theater in the fall of 1994? I don’t mean “right” in the sense of it being appropriate viewing for a divorced dad and his son—we were well past that already. In his dumpy bachelor pad in small-town North Carolina, on Wednesdays and alternating weekends, he’d play me VHS tapes of European sex comedies and low-budget shoot-’em-ups and serial-killer documentaries…anything to not have to talk. And compared to some of the fare we watched—say, a young David Thewlis licking chocolate off his bulimic lover’s breasts in Mike Leigh’s Life Is Sweet (1990)—Quentin Tarantino’s sex slave in a gimp suit was nothing to get squirmy about.

![]()

Amanda Plummer and Tim Roth in Pulp Fiction

![]()

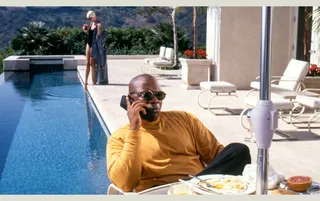

Uma Thurman and Ving Rhames in Pulp Fiction

No, what I mean is a more elemental sense of “can it be right”—i.e., is it true, did it happen or have I simply misremembered for the sake of the story? Arguing for the latter: At age 15, I’d have gnawed off a limb rather than go out in public with either of my parents. And having passed much of that summer on a dirtbag cocktail of painkillers and Wild Turkey, it’s not like I’m the most reliable historian of my own experience. On the other hand, Pulp Fiction was among the hardest of what we called the “hard R’s,” and I needed an adult to get me in. And when I grope back through the fog, there’s my dad, driving me home from the cineplex while explaining why I was wrong to love the film.

These associations might also account for the fact that after a few additional spins on VHS, I wouldn’t watch Pulp Fiction again for almost 30 years. Not to say that I didn’t think about it. Indeed, I’d have argued that it was the pivotal American film of the 1990s—the most influential, the most representative, and for long stretches, the best. To substantiate this claim, I’d have reached for the signifiers that encrust Pulp Fiction’s reputation and even on its release were part of its legend: the black suits, the ultraviolence, the catchphrases my buddies and I memorized (“Royale with cheese”). Not to mention the soundtrack—Kool & the Gang, Dusty Springfield, the Centurians—like a radio whose dial had come off somewhere in 1975. None of this stuff on its own, however, would have elevated Pulp Fiction above the sea of smirky postmodern cool I was already drowning in. So why had the film made such a deep impression? When I sat down to rewatch it again last week, I was confronted by an experience I’d somehow completely forgotten. What I’m trying to confess is that back there, in the darkness of the mid-’90s, I’d been moved less by the film’s bursts of sensation than I was by the transformation its characters are invited to undergo—one that passes beyond compulsive visual cool to a realm where life might have real and meaningful stakes.

Pulp Fiction original soundtrack

Now, I don’t think I’m alone in having neglected the emotional thrust of Pulp Fiction in light of its hype (Tarantino won the Palme d’Or). Indeed, the temptation to escape into pure aesthetics is the movie’s great subject. Like all of Tarantino’s work, Pulp Fiction offers the full panoply of cinematic thrills: come-ons and shoot-outs and dance-offs and capers. He’s been accused of nihilism, but really, this director is a vitalist, a heat-seeking missile for whatever brings energy to the screen. It’s why he keeps coming back to torture and swordplay. It’s why his soundtracks slap. It’s why he gravitates to questions of race, and to the word fuck in its many declensions. It’s why his radar for undervalued actors—Pam Grier, Christoph Waltz, even John Travolta (who, at the time of the movie’s release, was last paired with Bruce Willis in the Look Who’s Talking series)—is unsurpassed. Tarantino’s own cameo in Act III, as Samuel L. Jackson’s over-caffeinated friend Jimmie, suggests the jadedness of someone who’s worked too long in the video store. But I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that Tarantino’s real self-portrait is as young Butch (Chandler Lindauer) prostrate before the TV at the start of Act II, transfixed by the magic of the moving image. From this child’s-eye view, Pulp Fiction comes on like a giant hypodermic of adrenaline, with one almost pornographically vivid drop clinging to the tip.

Floating above that film, or running alongside it, is a second film in which a comparatively more sober and serious quality—call it the search for meaning—retains an animating force. Consider the opening diner scene where Amanda Plummer and Tim Roth psych themselves up for a robbery. You can see Plummer leaning forward as Roth talks, getting more and more turned on…by the time the guns come out, she’s literally salivating at her own audacity. But I’m struck by a seemingly tossed-off line along the way. Roth tells the story of a bank heist wherein a child is threatened with harm, and Plummer interjects, quietly, “Did they hurt the little girl?” This is an ethical, even a spiritual, concern, and if you tune your ear to it, the script is full of them: questions of duty, of right and wrong, of what John Travolta’s character calls “a moral test of oneself.”

The inhabitants of this second, more searching film are constantly looking for a way to dream themselves back into the first film—to “get into character,” as Jackson’s hit man Jules tells Travolta’s Vincent early on. Think of an off-duty Vincent shooting heroin in Act I for seemingly no reason other than to drive around L.A. looking cool with the top down. Or later, perched on the can, raptly paging through the kind of girls-and-guns novel that gives the film its title. Or consider the elaborate shadings of Jackson’s shakedown scene near the start of the film, moving from a folksy appreciation of cheeseburgers to a theatrical recitation of Ezekiel 25:17: “The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the iniquities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men.…” We’ve just seen Jules bickering backstage with Vincent, edgy as any other clock-puncher showing up for work in the morning. You sense a bad night of sleep, a dwindling bank account, a neglected love interest somewhere in the Valley. But the realities of his life fall away as he recites his chosen script, raising his voice, widening his eyes, warming to the role of a two-bit gangster. The only problem is that the words are empty: The violence that follows has nothing to do with righteousness. As Jules admits later, “I just thought it was just some cold-blooded shit to say to a motherfucker before I popped a cap in his ass.”

Pulp Fiction’s middle chapter, the story of Willis’s Butch and his missing watch, is the most memorably telegenic—from the bandage on the neck of the gangster Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames) to the black-and-white B-roll floating behind Angela Jones’s sexy cabbie to the series of wild coincidences that lands Butch alongside Marsellus in a redneck rape den. “The Gold Watch” is also, curiously, the most lifeless section of Pulp Fiction, and the one where it comes closest to the caricature of Tarantino as a superficial thrill-junkie. Only with the image of Rhames reduced to bondage does this part of the film seem to rouse itself…and even then it hastens to a Hollywood ending, the boy getting the girl and, after some banter about breakfast, riding off into the sunset.

“Its pretzel-like narrative structure is inseparable from its moral project.”

To close the movie here, at the chronological end of its plot, would be to cast a decisive vote in favor of pure pulp, as against the knottier quandaries we run up against every day. Which is to say that a younger Tarantino might have done it. An older Tarantino might have, too (see: Inglourious Basterds [2009]). But to end this, his second feature, the director takes a different path: One that leads the viewer back to the beginning of the story. And here we discover that Pulp Fiction’s most enduring legacy to ’90s cinema—its pretzel-like narrative structure is inseparable from its moral project. Retracing Jules and Vincent’s morning shakedown and the ambush that follows, we discover what we’ve been missing: that much of the movie to this point has occurred in the aftermath of a near-death experience. Facing Jules across a blood-spattered apartment, Vincent will insist that their emergence unscathed from a hail of bullets is a meaningless coincidence, a mere diversion from which no lesson can be taken. Jules, by contrast, sees it as a different genre of story: a miracle. As their argument breaks off and picks back up in the car and then at the diner where the film began, you can see Vincent growing defensive. You can even, if you want, look back and see his dope spree as a way of numbing the trauma before driving off to deal with Marsellus’s femme-fatale wife (the irresistible Uma Thurman). In any case, Vincent has made his choice: easier to remain in the role that almost got him killed than to risk something new.

But as Harvey Keitel’s fixer the Wolf says, “Just because you are a character doesn’t mean you have character.” In the movie’s career-making finale—chronologically, the scene right after the opening—we watch Jackson shepherd his hitman character from one category to the other. On pain of death, Jules deconstructs for a panicking Roth and Plummer the Bible passage that had so excited him earlier in the day. “Righteousness,” “iniquities,” “evil men”…any of it could mean anything, he admits. But he chooses to believe that it must mean something.

From left: Uma Thurman, Harvey Keitel, Quentin Tarantino, Bruce Willis and Maria de Medeiros in Pulp Fiction

This strikes me, in 2025, as not shallow but deep, the culmination of a movie that stages a series of confrontations between the aesthetic and the ethical, and asks protagonists and audience to choose: either, or both. Maybe, as Butch remarks to the cabbie, it “don’t mean shit”; my father certainly thought so. But maybe Pulp Fiction is what I thought it was, back when I was too young to know better: “a moral test of oneself.” Sometimes seeing really is believing.