Ghost Stories

By Leila Latif

The Act of Killing, dirs. Joshua Oppenheimer, Anonymous and Christine Cynn, 2012

Ghost Stories

How Joshua Oppenheimer’s astonishing documentary The Act of Killing spawned a microgenre of therapeutic nonfiction

By Leila Latif

January 22, 2023

None other than Albert Einstein is attributed (erroneously, as it happens) with saying, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over but expecting different results.” According to this maxim, repeating the past, particularly the painful parts, can only lead to further misery. But in the BAFTA-winning documentary The Act of Killing (2012), it is in the repetition that insanity is cast aside.

The Act of Killing is a trailblazing hybrid approach to documentary instigated by the Denmark-based American filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer, with Christine Cynn and an anonymous Indonesian filmmaker as codirectors. The film ingeniously uses re-creation to expose the brutality of Indonesian gangsters who led death squads that tortured and executed up to one million alleged communists during 1965 and ’66. The murders led to the fall of President Sukarno and the ascent of Suharto, whose brutal military dictatorship lasted 32 years.

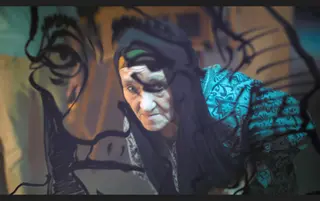

From left: a still from The Act of Killing; Four Daughters, dir. Kaouther Ben Hania, 2023

At the center of the film, which takes place in the present, is the aging and outwardly non-terrifying Anwar Congo, a slight and wrinkled man with a broad smile who is said to have personally killed a thousand people during his time in the Pancasila Youth militia. He, alongside some fellow cohorts, thinks nothing of Oppenheimer’s request to restage the murders. Seemingly enamored by being put on camera, they show no shame as they reenact the murders with all the casual glibness of a child reciting their lines in the school play for a grinning grandparent.

Though at first Anwar and his co-conspirators recount and demonstrate their actions with little remorse, their demeanours change when asked to reenact the murders in ever more elaborate styles, including re-creating their memories of murder in the manner of gangster, Western or even musical movies. Now the noose tightens around their necks in riveting and frequently bizarre ways, as Oppenheimer hands his subjects enough rope to hang themselves. Eventually Anwar breaks down as he confronts the pain he imposed on his fellow man, crying and retching at the murder site. Through this ingenious cinematic technique, Oppenheimer unveils the truth not by asking the butchers of thousands of Indonesians why they did what they did but simply by asking how. The re-creation process becomes like a form of behavioral therapy: Through repetition Anwar is able to see his actions for what they truly are.

Anwar Congo (center) in The Act of Killing

“By directing his subjects in theatrical retellings, Oppenheimer challenged the very notion of what constitutes a documentary.”

The film won an armful of awards, topped the Sight and Sound, Guardian and LA Weekly lists of best films of the year and was nominated for an Oscar, but its greatest legacy is how, over the decade since it first appeared, it has radically changed nonfiction filmmaking. At first The Act of Killing was termed a hybrid film, as it didn’t fit into the boxes that traditionally separate documentary from narrative features. Many film purists and proponents of direct cinema believe that documentarians should be passive observers who don’t interfere with the events they are recording. By directing his subjects in theatrical retellings, Oppenheimer challenged the very notion of what constitutes a documentary. And while The Act of Killing is hardly the first to engage in this method—hybrid documentaries have been around since Robert J. Flaherty's Nanook of the North (1922), and Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (1988) famously used reenactment to exonerate a man falsely convicted of murdering a police officer in cold blood—it was a film that upended the genre and inspired a whole new generation of filmmakers to follow suit. This year alone, the two films at Cannes that shared the L’Oeil d’or prize for best documentary, Kaouther Ben Hania’s Four Daughters and Asmae El Moudir’s The Mother of All Lies, deploy this approach, as did Lina Soualem’s London Film Festival Best Documentary winner, Bye Bye Tiberias.

Stills from The Mother of All Lies, dir. Asmae El Moudir, 2023

Unifying all these films are the moments where the protagonists ultimately acknowledge how the specters of the past will never stop scaring them. In The Act of Killing, these deep-rooted psychological strains are vocalized by Anwar when he states, “There are many ghosts here because many people were killed here.” Likewise, Bye Bye Tiberias’s director, Lina Soualem, manifests hidden scars, albeit in a gentler storyline. Filmed before the current conflict in the region escalated in October, she takes her mother, Succession star Hiam Abbass, back to her childhood home in a Palestinian village, where she re-creates two scenarios between Abbass and her sister where the actor was struggling with her decision to leave. Ultimately, Abbass decided to move to London and then Paris for love, marrying for the first time, and this determination, self-belief and risk-taking proved foundational to her path as a celebrated actress. Even after raising two daughters with actor Zinedine Soualem, including this documentary’s director, Abbass never shook off the desire to return to Palestine or assuage her survivor’s guilt. What’s intriguing is the sense that acting has allowed her to cope with her past by pretending to be someone else, and her director-daughter asks Abbass to act and pretend to be her younger self in the film’s specific restaging to allow her to unburden her emotions. At one point Abbass pleads with her daughter: “What are you after, Lina? It was very hard for me.” There is the atmosphere of a séance, bridging the gap not to the afterlife but to prior figures and events that haunt us. Restagings make the past corporeal for the subjects in a way that reviewing footage of the event would not. Re-creation also fortifies the foundation of many classic ghost stories, showing how something can be suppressed but not escaped and must eventually return. In the case of Bye Bye Tiberias, it is not just Abbass who seems haunted by the past, but also her sisters who opted to stay in a Middle East forever scarred by violence and displacement.

From left: Tayssir Chikhaoui, Olfa Hamrouni and Eya Chikhaoui in Four Daughters

In Four Daughters, Olfa, a Tunisian mother, and her daughters Eya and Tayssir confront the loss of two members of their family who left home as teenagers to join ISIS by replaying what happened with actors standing in as the missing siblings and the Tunis-born Egyptian superstar Hend Sabry stepping in for the mother whenever she felt emotionally unable to take part. The film taps the palpable despair experienced by the family and community the girls left behind. At times the actors and their subjects are interviewed together, and it’s only in seeing Sabry interpret events from her own past that Olfa feels strong enough to participate in revisiting her trauma and begins acting herself. The film is at its most fascinating and moving when Olfa, Eya and Tayssir take in the re-creation, either by watching or enacting the scenes, and they are forced to confront old wounds and revisit the now painful memories of when their sisters were still home. Olfa’s interpretation of scenes suggests how the seeds of the sisters’ discontent were sowed, and the story shifts emphasis from being about sisters joining ISIS to sisters escaping their mother by any means necessary. When Olfa rather than Sabry tackles a scene, small changes in accent and emphasis speak volumes about Olfa’s worldview. Like therapy, the process unpacks the story of the family’s past and helps them cope with their worst nightmare.

Of the 2023 crop, perhaps the film to depict the most shocking cruelty is The Mother of All Lies. Moroccan director Asmae El Moudir returns to her family home in Casablanca, and using tiny, gnarled-looking puppets as stand-ins, exposes the intricate web of lies spun by her grandmother about their family. Possessing only a single photograph of herself from childhood, El Moudir challenges the matriarch about the inconsistencies of her own origin story. The director is unconvinced that she’s really the child in the picture and is determined to make a film that shines a light on the truth, despite her grandmother’s unsurprising reluctance to be confronted onscreen.

From left: a still from The Act of Killing; the poster for Bye Bye Tiberias, dir. Lina Soualem, 2023

With the help of her father, El Moudir painstakingly re-creates their family home and its surrounding neighborhood on a soundstage. She brings family, neighbors and friends to take part in the interrogation and collectively acknowledge what really happened, an undertaking that excavates historical ambiguities, political unrest and a possible military cover-up. Despite the decades that have passed, reopening these memories proves both painful and cathartic for the community. One participant is overwhelmed by the site of the cell he was imprisoned in back in the 1980s; others seem unburdened by secrets that finally allow the dead to rest in peace. There’s a fallacy in believing that all these scenes reveal a single knowable gospel, given the subjectivity of the participants and filmmaker, not to mention the ultimate subjectivity of memory. But emotional honesty can be a step toward healing, even when puppets are employed in lieu of the witnesses themselves.

No person or place is unaffected by being observed by a camera, and as Oppenheimer himself said in 2016, “Documentary is film where people play themselves.” The additional level of performance he and subsequent filmmakers have included within their work has not only created fascinating and breathtakingly tense cinema but, as Oppenheimer puts it, “necessarily tentative, exploratory, archaeological excavation.” Restagings make the past corporeal for the subjects in a way that reviewing footage of the event would not, he explains: “We invent new realities together with our characters, creating situations that shed light on them and their worlds, just as one might apply lamplight to a crystal, searching for just the right angle so that, in a moment of clarity, the crystal’s complex architecture shines forth, revealing its multiple facets.”