Great Theaters: Le Drugstore Saint-Germain, Paris

By Colombe Schneck

A childhood reminiscence on watching Truffaut’s Small Change at Paris’s famous bohemian cinema

BY COLOMBE SCHNECK

July 2, 2024

Small Change came out in theaters on March 17, 1976. That very evening, my mother and father, 7-year-old sister, 12-year-old big brother and I, age 9, attended the 8pm screening. There was school the next day and usually at that hour we’d be getting ready for bed, so it was clear to all of us that this movie night was a special family occasion. The film was playing at Le Drugstore in the 6th arrondissement, right next to Brasserie Lipp (where if you were not a regular there was no point in trying to get a table) and across the street from the Café de Flore and the Les Deux Magots (where we’d never go, not our style, too glitzy, too touristy). We lived ten minutes away by car, on the other side of the Luxembourg Gardens, in a far quieter neighborhood. Anytime we got to go to Le Drugstore for an American-style dinner and to take in a movie was a treat. And Le Drugstore was a little slice of America (albeit with a thick French accent) right in the heart of Paris. When it opened in October 1965, the correspondent Janet Flanner wrote that “the French are now Americanizing Saint-Germain-des-Prés,” as they had done previously with Le Drugstore’s first location, on the Champs-Élysées. But the one-screen movie theater inside Le Drugstore Saint-Germain also hosted highbrow film premieres, like Federico Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits.

Le Drugstore turned out to be a staple for the famous artists living within walking distance. Serge Gainsbourg would buy his cigars there with a billet of 500 francs, never asking for change. The musician Jacques Dutronc dedicated a song verse to the place, “petits minets qui mangent leur ronron au Drugstore”: little twinks who eat their purrs at the Drugstore. Le Drugstore was located in a traditional Haussmann limestone building, its ground-floor shop windows gleaming with dreamy items you’d only heard about: the Sony Cube radio alarm clock and Sony’s first Walkman, the punk jewelry designer Dinh Van’s gold handcuff bracelet and razor blade pendant, Mason Pearson hairbrushes from London and Fruit of the Loom T-shirts. Inside there was a pharmacy, a newsstand with international papers, a bookshop and a restaurant that served such oddball delicacies as Hawaiian toast, my favorite, a croque monsieur with a slice of pineapple.

On the night of the Small Change screening, we’d eaten at this restaurant, and afterward, standing in a long queue for tickets at the downstairs movie theater, we worried that maybe we’d lingered too long at the table and wouldn’t get seats. In a tech innovation not unlike reserving seats online, there was a map of the theater at the cashier with lights showing which seats were still available inside. It added excitement and despair to the experience, because you could watch the rows filling up as you waited.

Finally it was our turn. My father handed a 50-franc note to the cashier for the five tickets. I can still picture this note, which we called “Pascal” in France. I was impressed by the enormity of the sum and worried that my father was going broke. I was an anxious little girl.

Soon we were in, the five of us in a row, and I could relax. Did I know that two years earlier, in 1974, at 5:10pm on a Sunday in mid-September, Carlos the Jackal tossed a grenade from the balcony of the mezzanine restaurant onto the shopping arcade below? Two were killed, and 34 were wounded. Was I aware that 10 days after Le Drugstore’s inauguration, the Moroccan dissident and left-wing revolutionary Mehdi Ben Barka was kidnapped on the sidewalk right out front as he went to meet director Georges Franju and writer Marguerite Duras at Brasserie Lipp to discuss a film project concerning decolonization? He disappeared forever, his body never found.

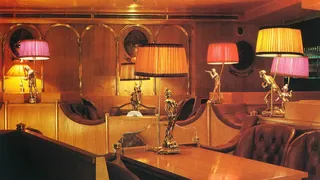

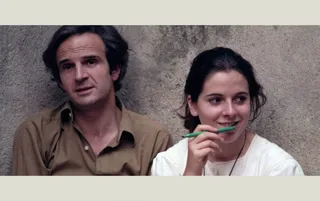

From left: Le Drugstore Saint-Germain in 1967; the restaurant inside Le Drugstore Saint-Germain; François Truffaut on the set of Small Change

In our seats, the “séance” started: 30 minutes of ads (the best was the one for Dim stockings, with its wonderful tune) and sometimes a short film before the feature began. The cinema had a luxurious decor, far more so than the Montparnasse cinemas where we usually went. The walls were clad in cherrywood, and the seats were covered in thick tan leather. Polished glass globes illuminated the room. The New York Times described the décor as “fraudulent fin de siècle” style at the time, but I loved it. The reason for this special outing had less to do with the theater than with the fact that my parents “loooved Truffaut.” I can now understand their connection with the director. They were all born in the same year, 1932, and shared a similar sad and lonely childhood during the war. In 1968 Truffaut learned that his biological father was a Jewish dentist. My parents are both Jewish doctors. What happened to them in their childhood isn’t something we talked about—how at the age of 8 they both became instant pariahs and went into hiding for four years, but it was something they could only share wordlessly with others with the same history.

“It’s a film about children,” our father explained to us, “but it’s not a film for children.” I had already seen black-and-white films by Truffaut, like The 400 Blows and the later Doinel series, about a drifter looking for love. I enjoyed them, but I was excited by the idea of a film populated with children of my generation—children of the ’70s, wearing blue jeans and colorful shirts in what looks on the surface like a carefree world. These children might share my hidden worries and make me feel less alone.

The film follows the lives of two school classes in Thiers, France: the younger kids with their kind teacher, and the adolescents with a stiff teacher who tries her best. Instead of an overarching plot, the film is more a succession of short stories that lead us to the big summer holiday. I’m each of the children as they appear. I’m Patrick, with his smooth blond hair, played by Georges Desmouceaux, the son of Claude de Givray, one of Truffaut’s screenwriters. Patrick tries to kiss a cute girl (played by Truffaut’s daughter Éva) at the cinema, but is far too shy. Patrick is reasonable and cares for his disabled father. Don’t I also have a mother who has problems? I don’t know exactly what kind; it is related to the war. I must be careful, protect her and never put any worries in her head. Patrick is in love with his friend’s mother. She kisses and caresses her own son, but he pushes her away and Patrick looks at them with envy. I am in adoration of my friends’ mothers, those who kiss and caress their children. My mother is a brunette Catherine Deneuve with green eyes, a tiny nose and the same distant elegance. She smiles sometimes, but I can’t remember if she ever kissed me.

“It’s a film about children,” our father explained to us, “but it’s not a film for children.”

I know I’m very lucky not to be Julien (Philippe Goldmann); his jacket and pants are torn, and he steals from the pockets of other students; his little body is covered with burns and bruises. As a teacher later remarks, “The world isn’t always fair…and the injustices to children are the most heinous.”

I’m Sylvie, played by Sylvie Grezel, because she’s cute with her long hair and I have almost the same ruffled dress as she does. She throws tantrums and wants to be cared for and pitied. She dares to do what I never could, and for this reason I admire her. After one tantrum, her parents leave her alone at home to go have lunch in a restaurant, and she shouts through a bullhorn, “I’m hungry, I’m hungry,” from the courtyard window. The neighbors use a rope to send a basket of food to her. The basket contains a roast chicken, a brioche and a Camembert.

I am also Martine (Pascale Bruchon), who spends her holidays at summer camp, walking and smiling, and like her, there is always a boy who makes my heart beat. I’m Martine, the one who kisses Patrick at the end.

In the car home after the film, my siblings and I repeated lines from Small Change. “Grégory went boom!” exclaims the little boy in the film after he falls from the 10th floor of a building without hurting himself. “Thank you very much for this frugal meal,” Patrick announces to his friend’s mother after a sumptuous dinner. And when Patrick gives her flowers that he had paid for with his pocket money, she misunderstands and replies, “Give my thanks to your father.” These are not actors, characters or scenarios; I have no doubt in my mind that every single detail of it is true. I know these children. I grew up with them. The authenticity is thanks to Truffaut and his co-screenwriter, Suzanne Schiffman. They talked and listened to the children on set. Each Sunday, after a week of shooting, Truffaut and Schiffman would use these stories they heard and write the lines for the following week. Small Change is not a documentary; it’s fiction that shows how much children depend on the goodwill of adults. If they are harsh or selfish to them, growing up can turn into despair.

Truffaut used to say that he loved kids to the point of being an “idiot” with them. And you can feel this love in the film. In the last scene, set at summer camp, the kids at lunch play a trick on Patrick, telling him to go out to the stairwell, “Martine is waiting for you to kiss you.” They also tell Martine, “Patrick is waiting for you to kiss you.” But it turns out not to be a terrible trick: That’s how he kisses his first girl.

![]()

François Truffaut and his daughter Laura on the set of Small Change, 1975

![]()

Philippe Goldmann in Small Change

This actually happened to François Truffaut as a kid; that’s how he too had his first kiss. It makes for a tender and happy ending. Our father told us it’s important to make happy memories. I often go back to this last scene in the film and remember our evening at Le Drugstore. That’s the way in Paris. Le Drugstore itself took the place of an old café, drawing complaints when it opened but also opening itself to new memories for my generation.

Years later my family repeated, “Grégory went boom,” to each other, proof that the film had insinuated itself in our own mythology, an inside joke to commemorate that sometimes catastrophe can end well. My siblings and I also repeated, “Thank you for this frugal meal” to our parents. It was a way of indirectly saying thank you for taking such good care of us. To us, Small Change was a movie about our own young lives, and to my parents, it was a reminder of their own before the war. This is what childhood is, Truffaut tells us on the screen. This is what it looks like.