James Schamus: Indie Cinema’s Golden Touch

By Phil de Semlyen

Brokeback Mountain, dir. Ang Lee, 2005

James Schamus: Indie Cinema’s Golden Touch

By Phil de semlyen

So what exactly does a producer do? The industry legend demystifies a career of award-winning collaborations with Ang Lee and others

August 8, 2024

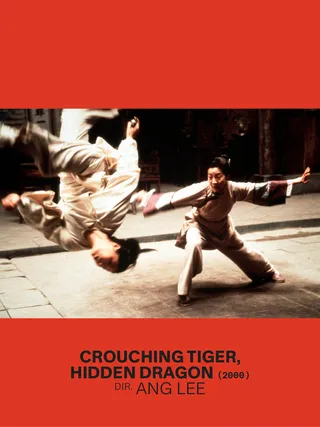

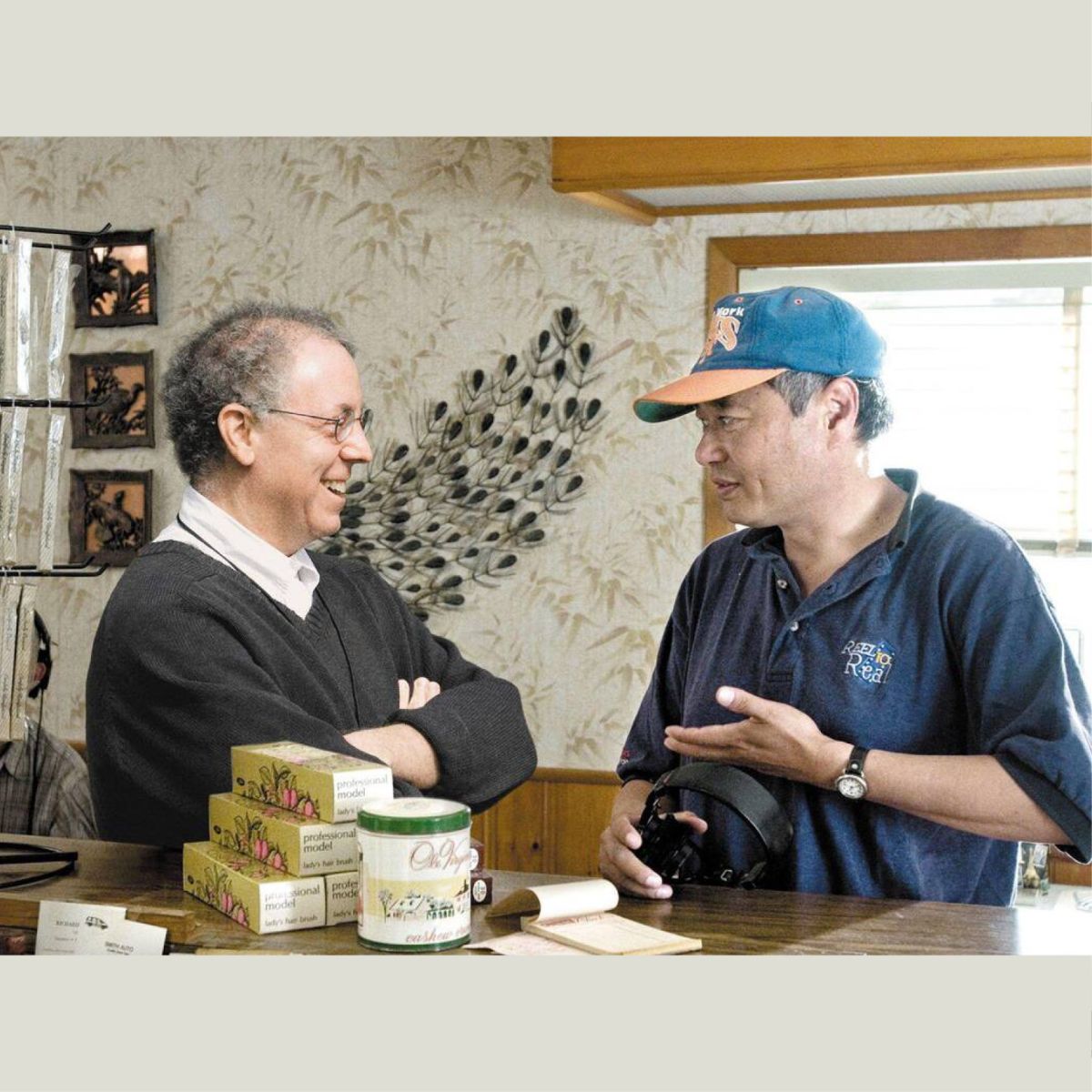

James Schamus and Ang Lee on the set of Taking Woodstock, 2009

Producer, screenwriter, director, studio head, film professor…Detroit-born, Los Angeles–raised filmmaker James Schamus has done it all. But he is perhaps best known as Ang Lee’s right-hand man: writer-producer on Lee’s enduring classics like Eat Drink Man Woman (1994), The Ice Storm (1997) and Lust, Caution (2007), and producer on the taboo-busting, eight-time Oscar-nominated Western Brokeback Mountain (2005). There’s also been Academy Award recognition for his epic martial arts screenplay for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), an adaptation of Wang Dulu’s Chinese wuxia novel.

Schamus’s reputation for bringing artist-led masterpieces to the big screen was burnished during his time as top dog at Focus Features, a studio he co-founded in 2002 and left 11 golden years later with a back catalog boasting Todd Haynes’s Far from Heaven (2002), Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (2003), Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) and Martin McDonagh’s In Bruges (2008). In 2015 he stepped behind the camera with panache as writer-director of Indignation (2016, shot by Christopher Blauvelt), a take on Philip Roth’s campus coming-of-age story. He hopes there’ll be more.

Artist-led indies are where Schamus’s heart lies, but his journey to producer started, incongruously, with a clammy hostage thriller—of sorts. Freshly arrived in New York, Schamus found work as a $50-a-day production assistant, constructing dramatic re-creations for an ABC news program. “We built the dungeon, in which we had assumed a bunch of American hostages were being held in Beirut, on a soundstage on East 33rd Street and Eleventh Avenue,” he remembers. “I should check my IMDb page to see if I ever got credit for it.” Schamus also teaches film history and theory at Columbia University. Erudite and affable, even when being interrupted by the honk of trucks outside his Upper West Side apartment, he took time out of an intensive TV writers’ room to provide an insider’s guide to the misunderstood art of being a producer.

![]()

![]()

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, dir. Michel Gondry, 2004

A producer has many hats: financier, diplomat, entrepreneur, leader, psychologist, artist. Am I missing anything?

Bully, thief, huckster, salesperson, sociopath, people person…that pretty much sums it up. [Laughs]

For you and Ang, it all began with filming Pushing Hands (1991) and The Wedding Banquet (1993) in New York. Did that feel like a film school for you?

For me, yeah, because I had no skills. I landed in New York in 1987, working on a dissertation for the University of California, Berkeley. But I fell in with the wrong crowd and ended up meeting Todd Haynes, [producer] Christine Vachon, [producer] Ted Hope, [Swoon writer-director] Tom Kalin and many more, and I just pitched in. They had more experience than I did, but I was happy to pretend to have expertise in raising money. The business part of independent film was still fairly inchoate at that point: You could just send a fax to the commissioning editor at Swedish public television [Sveriges Television, or SVT] and sell them a 16mm film for $5,000 by someone they’d met at the Rotterdam International Film Festival. I quickly self-educated by reading tons of contracts.

So we need to add “lawyer” to that list of a producer’s roles?

Pseudo lawyer. But reading contracts was the education. When you watch a film, you’re looking at the result of between 1,000 and 4,000 contracts. If any of those contracts are problematic, the film doesn’t appear onscreen.

You famously said that Ang’s first story pitch was terrible. He says that you reminded him of a “salesman and a professor.” Is that a fair description?

I still have more than a residual amount of hucksterism in my DNA. But the idea of a pure artist who is struggling to retain their voice within a corrupt system is an utterly false notion. The minute you make a narrative feature film that could be released by a distributor, then, I’m sorry, but you check a lot of the “pure” part at the door. That doesn’t mean that what you’re fighting for as an artist and a human being isn’t all the more important.

Have his story pitches got better?

No, they’re still terrible! [Laughs]

You went from those first two films to Eat Drink Man Woman and Sense and Sensibility (1995) with Ang—both in cultures that were unfamiliar to you. What was your approach to producing in a foreign language?

It’s the same [as working in English]: Get good people with whom you can ask stupid questions. People are very afraid of appearing dumb in this business. There are two kinds of asshole directors: The first always pretends they know the answer to everything even if they don’t know shit, and the second gets overwhelmed. When I was directing Indignation, I’d tell my team that I was going to ask them, unembarrassed, the stupidest questions they’ve ever heard but that I’d always make a decision and I’d never leave them high and dry. Because being a director means making about 2,000 decisions a day. That’s how I frame the advice I give to producers: If you knew everything, you’d have no need to hire really good people to do their jobs.

The Assistant, dir. Kitty Green, 2019

“The idea of a pure artist who is struggling to retain their voice within a corrupt system is an utterly false notion.”

Is that a lesson you learned early?

When I first came to New York in the ’80s, I was working as the world’s oldest production assistant. I’d go on set and the producer there was just so in charge. He’d have this person carry around these gigantic notebooks with the script, the schedule, the budget—he’d be shouting at a key grip to move a C-stand. The next day I’d go on another set and that producer would be at the craft-service table, cracking bad jokes, buttering up the lead actor, being a complete doofus. It was only later that I realized that producer A was a terrible producer and producer B was the genius. He’d brought together all these people and he had nothing to do, and the other producer is telling people how to do their jobs. Your goal as producer is to have nothing to do. You never attain that goal—there’s always problems to solve—but the closer you can get to being useless, the closer you get to being a really good producer.

How hard does it hit you when a film doesn’t come together, like your Muhammad Ali movie with Ang?

I don’t get too depressed. I love the work so much that I’m grateful to have had the time [on it]. On Thrilla in Manila—or Frazier/Ali or whatever we’re calling it—it was insane. Years [of work]. And it’s not dead either, by the way. It took us eight years to get Brokeback Mountain made. That died so many times it was a laughingstock. Even when it was finally green-lighted, it was “the gay cowboy movie that no one will see anyway.” We were like, Okay, here comes some career suicide, [but] as long as we’re still kicking…

What can you do as a producer when a film goes into turnaround like that?

It comes down to how many nickels you need to rub together to get Ang’s or whoever else’s vision in front of the cameras. If the nickels don’t add up or elements drift away, you have to start all over again. The Assistant [directed by Kitty Green, 2019] is a good example: That was the single most difficult film I have ever attempted to put together, including Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. We saw [The Assistant] nuked a number of times before we were finally able to put it back together and into production. There were a lot of people who really did not want it to happen. We kept saying to people, “It’s not a personal attack on you or the time you spent opening the door to Harvey [Weinstein’s] office when you were getting started in the business.”

Ang is seen as someone who can take a subject from outside his cultural base and make something extraordinary of it. Have you helped to break down boundaries around who can tell what stories in Hollywood?

I would hope, but I don’t think so. Hollywood already had a very long tradition of, for instance, outsiders telling American stories and certainly of embracing a bunch of suburban white Los Angeles people making stories about a lot of other people who live differently. Then, in the 1930s, you had a wave of German and Austrian-Jewish filmmakers in Hollywood.

![]()

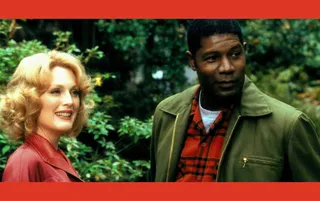

Far from Heaven, dir. Todd Haynes, 2002

![]()

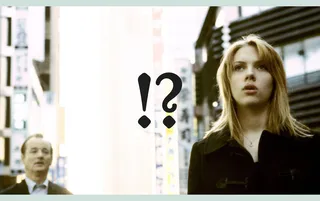

Lost in Translation, dir. Sofia Coppola, 2003

But you are talking specifically about white men.

I am, but back then the studios—which were mainly run by Jewish guys—didn’t particularly like people to know that there were Jewish people in town, and they didn’t make movies about Jewish people. These are complex histories. Along comes Ang, and John Woo and Jackie Chan, so there’s always been some flow through the system, but it’s not been much. The fact is that the system is part of larger systems that are what we’d call racialized capitalism, and it’s an interesting dynamic because for decades the most racist part of that system was the art-house circuit, which was conditioned by the assumption of the whiteness of its audience in the West. If you were a Black person and not making movies that featured large amounts of hip-hop and gang stuff, where did you live? When we came out with Crouching Tiger, I would often go to Q&As made up mostly of people who look like me. I’d ask them what the average spectator of the top-10 highest-grossing non–English language films to date looked like, and they’d say, “Kinda like us,” and I’d say, “No, it’s a young Black guy.” Literally seven of those movies were subtitled kung fu movies, and it was young Black people who were flocking to see them. It wasn’t people like me, from the Upper West Side of Manhattan. That’s global culture at work—it’s completely racialized.

The Assistant has been hailed as one of the first #MeToo movies. Are you drawn to films that drive cultural change?

People have always asked me if I have a political filter for the work I do, and that would be a very reasonable assumption. And in fact it’s more or less correct. But no one would ask that question of me if at least a handful of the films I’ve worked on weren’t considered to be really good. But the thorny question is: Who’s in charge of deciding what’s good or not? What are the politics of that? In answer to your question: Yes, I do have that filter. But I find that it needs fine-tuning every day.

Thirty years on, does it still give you a buzz to be on set?

Yeah, absolutely. But I’ve stepped back a lot the last few years to make more space for my creative work and writing.

What’s your on-set comfort?

Unfortunately the craft-services table is a danger zone for me. The overladen craft-services table is almost unique to American film culture—you don’t have it in other countries. But you’ll find the biggest on-set topic of conversation for producers of a certain age is what kind of winter jacket you’re going to wear on that night’s shoot. It’s a big deal.

You wrote, directed and produced Indignation. How difficult is it to block out the producer’s concerns when you’re writing? Is compartmentalizing your superpower?

“Compartmentalizing” assumes a purity of the endeavor that’s never there. The screenplay is just a document to persuade people to do a lot of stuff and spend a lot of money. With Indignation there was a shared sense of authorship with Philip Roth, the writer of the novel, which weighs heavily. But on the other hand it’s rare in the art-house world to have somebody who’s a screenwriter and producer, and it jars against the notion of auteurism. Yet I got to be screenwriter and producer for one of the great cinema auteurs who’s ever lived, Ang Lee. That’s paradoxical, isn’t it? And at the same time, I’m working under the shadow of one of the most successful periods in the history of audiovisual media: the HBO-era of peak TV, a medium completely run by writer-producers, or showrunners, who hire directors to do the dirty work.

![<I>Sense and Sensibility</I>, dir. Ang Lee, 1995]() Sense and Sensibility, dir. Ang Lee, 1995

Sense and Sensibility, dir. Ang Lee, 1995![<I>The Wedding Banquet</I>, dir. Ang Lee, 1993]() The Wedding Banquet, dir. Ang Lee, 1993

The Wedding Banquet, dir. Ang Lee, 1993![<I>The Ice Storm</I>, dir. Ang Lee, 1997]() The Ice Storm, dir. Ang Lee, 1997

The Ice Storm, dir. Ang Lee, 1997![<I>Lust, Caution</I>, dir. Ang Lee, 2007]() Lust, Caution, dir. Ang Lee, 2007

Lust, Caution, dir. Ang Lee, 2007

Do you see yourself as a trailblazer in that role?

It wasn’t really trailblazing. It was simply allowing for both ideologies. My being a showrunner in the independent world didn’t mean that Ang was anything less than an astonishing auteur—the two were functioning together, and they can, honestly. But it’s tricky because you have to have a deep respect for your collaborators that never oversteps into their space to create.

You’ve made so many films that live in the canon. Which one are you most proud of as a producer?

It’s not the most obvious. In Ang’s body of work I’m not surprised when I get emails about The Ice Storm or Crouching Tiger, but I’m very pleased when I get long missives about Ride with the Devil [1999] and I’m super happy when people finally get around to responding to Lust, Caution. Of all my films with Ang, that’s the one I’m most proud of. It’s one of his masterpieces.

Lastly, what do you like most about Ang?

Most of all I love his ability to remain astute. There’s obviously an unbelievable will and drive, and the clarity, vision and commitment is just astonishing. But accompanying that is the sense that every day he’s going to learn something new. Even though he’s among the older hands at this stuff, he’s still one of the real beginners. That’s the spirit we’ve been able to maintain during the 11 films we’ve done so far—maybe there’ll only be 11—and the spirit in which we still conduct our conversations.

What’s the last conversation you had with him about a collaboration?

Last night. I don’t pitch projects to him, but there are a couple of things that are possible. I’m happy to live a life where I’m, quote, not his producer.

If you were a betting man, would you put money on there being a 12th Schamus and Lee movie?

We’re both really happy not knowing the answer to that. It takes a lot of pressure off everybody and we can really enjoy our time together. But I’d be thrilled to do another one. At the same time, right now I’m helping out a lot of young people, too. I’m committing to the margins of the business—extremely low budgets, first-time filmmakers, relearning how to handcraft movies—and I’m truly enjoying it.

Indignation, dir. James Schamus, 2016