Killer Inside

By Andrew Durbin

Elephant, dir. Gus Van Sant, 2003

Killer Inside

What Gus Van Sant’s elusive Elephant has to say about the shooters—and about us—20 years on

By Andrew Durbin

February 20, 2024

I first watched Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003) when a boy from high school invited me into his bed. We spooned with his computer propped on the edge of the mattress. He had already seen the movie and couldn’t believe I hadn’t. Of course, I’d heard of it; everyone had. Two boys shoot up a high school, just like Columbine. Back then, in the early 2000s, mass killings were still rare, and the thought of watching a quasi-dramatization of the most famous one, especially a film in which the killers were hinted to be gay, unnerved me: Only 16 years old and closeted, I was sensitive to the notion that my secret was part of a great evil poisoning the world, an argument in heavy supply in my religious hometown down South. I felt my friend’s erection press against my back as the film tracked the lives and eventual deaths of various suburban high schoolers our age, played by nonprofessional actors. Did he find the strange romance between the two shooters hot, this mix of awkward teenage normalcy and explosive violence? Elephant must have confused him, as it confused me. When I left his bed I vowed, a little self-righteously, never to see it again.

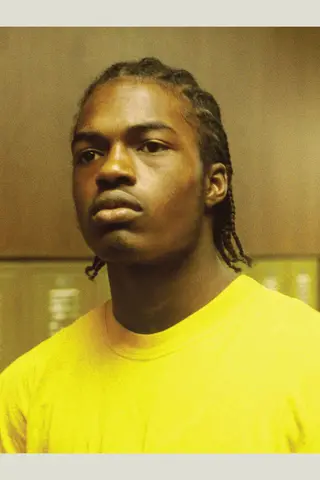

From left: Brittany Mountain, Carrie Finklea and Jordan Taylor; Bennie Dixon

Twenty years after its release, I saw Elephant for the second time. The film is short, roughly 80 minutes. Van Sant first conceived it as a television documentary about the 1999 Columbine massacre but abandoned the idea after Barry Diller, then head of USA Networks, became squeamish about depicting the scale of unremitting violence seen at the Colorado high school. Instead, Van Sant decided to fictionalize the mass shooting, transferring it to Portland, Oregon. Most of the student actors play versions of themselves. They improvised the film’s dialogue as well as most of its scenes—up to the point of the killings. The film has often been compared to a 1989 BBC short about the Troubles (also called Elephant), which offered no answers to the cycle of political killings in Northern Ireland. Though they share a title and a disinterest in any moralizing viewpoint, Van Sant has denied seeing the earlier Elephant before making his own.

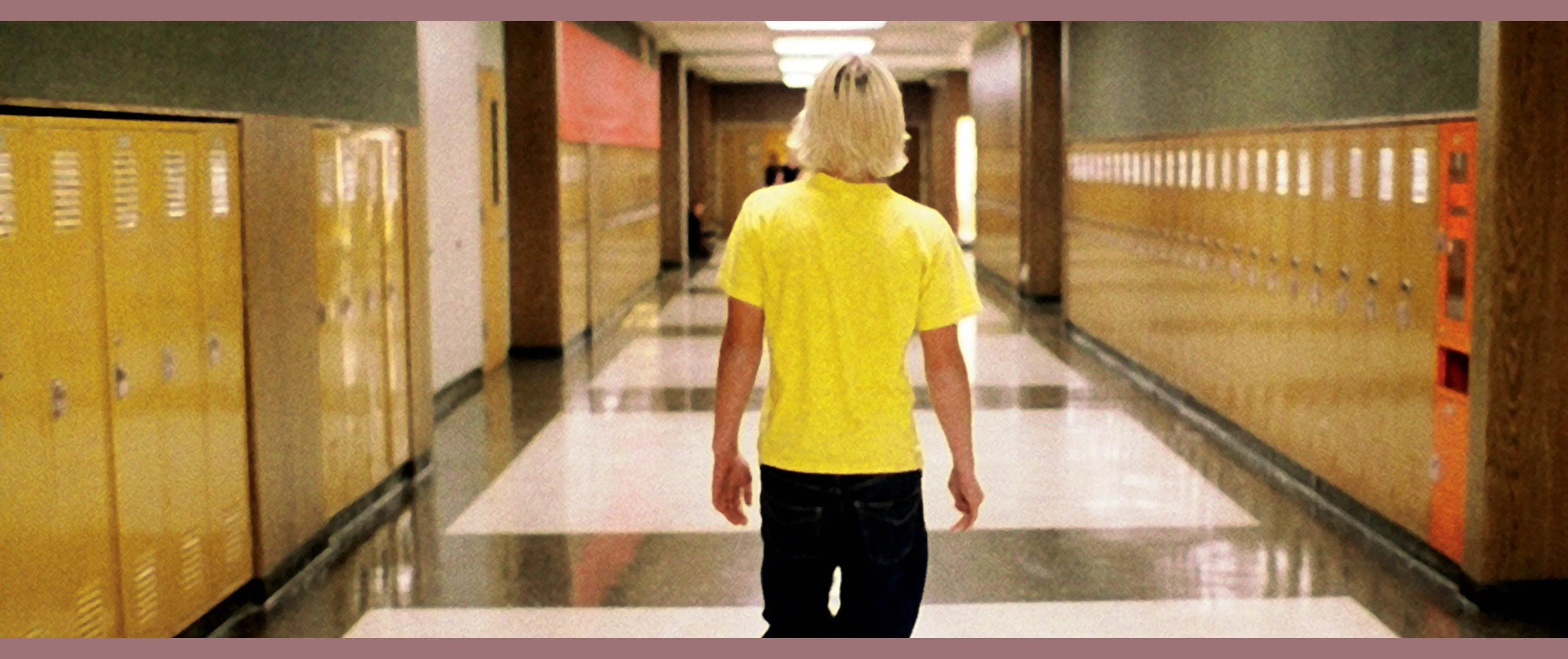

John (John Robinson), with long, wispy blond hair and a yellow T-shirt featuring a black bull, is the first of the students to appear. He drives to school rather than allow his drunk father behind the wheel. From above, we watch the car glide through a suburban road littered with fallen leaves. It’s the beginning of the school year. Another student, Elias (Elias McConnell), is a lanky, nervous-looking photographer at work on his portfolio at school. The local punks ask whether he wants them to pose nude—that won’t be necessary, he blushes. Brittany, Jordan and Nicole (Brittany Mountain, Jordan Taylor, Nicole George) flirt with boys and banter about their lives, and after lunch they enter the toilet to forcibly vomit their meal. What these teenagers know about one another seems purely emotional, intuitive: They gossip, crush, search each other for signs of recognition, understanding, care. When one girl finds John crying in an empty room, she asks him, “What’s wrong?” “Nothing,” he replies. She kisses him on the cheek.

From left: Alicia Miles and John Robinson in Elephant

The camera roams the hallways, tracking one student after another in a sequence of nonlinear, impressionistic vignettes that shirk plot and, after the shooters are introduced, straightforward answers. Their lives are seen by us in an intimate square—the film was shot in a 1.1:33 aspect ratio—meant to evoke old educational films, Van Sant has said. This starkly non–widescreen format draws the figures close while trimming the margins, putting on blinders to any dangers lurking on the sidelines. The film’s soft, disarming palette is dappled by the liquid Pacific Northwestern light and darkened by the shadows of a public institution eventually transformed into a killing ground. How could anything terrible happen here? Van Sant’s mode of nonnarrative filmmaking avoids overt commentary—the film is one in the director’s “Death Trilogy,” based on real-life tragedies including the suicide of Kurt Cobain (Last Days, 2005) and the murder of the hiker David Coughlin (Gerry, 2002). As the writer and critic Katya Tylevich notes in her book about the director, Elephant refutes a simplified chain of cause and effect so often prescribed by the media after these disasters: because they listened to Marilyn Manson…because they played violent video games.… “So, what happened?” Van Sant asked himself in the aftermath of Columbine and Cobain’s death. “As I got closer to the subjects, the answers grew more elusive. My answer to what happened is: ‘Probably not much. It was probably pretty boring.’” Tylevich adds that Elephant “withholds drama from tragedy and strips it of narrative, a transgression against contemporary moralizing and public discourse. After all, media runs on narrative.”

It is impossible to watch Elephant now without thinking of the world that followed it. We no longer fret so much over a shooter’s motivations to kill; our collective moral failure to do anything about it—anything at all—is the more paralyzing problem. Van Sant subtly anticipates this sense of powerlessness with his camerawork, following just behind the characters, always lingering briefly on details, unable to intervene, refusing to impose meaning upon the moment. To this end, the camera is possessed with an all-seeing eye that moves backward and forward in time, and yet it is passive, ineffectual, always playing catch-up to a story whose outcome is already set in stone. It captures scenes as if by accident, like the first time we see the shooters, Alex (Alex Frost) and Eric (Eric Deulen), arrive at school in camo garb with bags of guns, explosives and knives in tow. The camera very nearly misses them.

“We no longer fret so much over a shooter’s motivations to kill; our collective moral failure to do anything about it—anything at all—is the more paralyzing problem.”

When Alex and Eric first receive a gun in the mail, they’re watching a documentary about the Third Reich. “Who’s that guy?” Eric asks after an image of Hitler flashes on TV. In another scene, Alex plays Beethoven’s “Für Elise” and Moonlight Sonata at the piano while Eric fixates on a first-person shooter game featuring characters from Van Sant’s Gerry. Though they exhibit some boyish sweetness in the scenes that lead up to the killing, their apparent creativity and love of beauty (notice how seriously Alex takes his Beethoven) can’t squash the ultimate desire to murder their classmates. It may even be entangled with it, with the ancient superstition that death is the greater freedom. This was a point Van Sant recently made to The New York Times. For the shooters, he explained, “[t]he conformity of society is so oppressive—as far as get good grades, play sports and don’t be an outcast—they’re reacting in a very violent way against it.” In other words, play God to escape high school, and from the divine plane decide who lives, who dies.

Only the final 20 minutes of the film depict the murderous act, beginning with Alex and Eric hunched over a map of the school—a scene intercut jarringly with the first shots fired. “We should be able to, you know, pick off kids as we traverse the east wing,” Alex says. “Like, dumbass jocks…we’ll have a fucking field day.” The narrative pace accelerates as the disparate protagonists are brought together in tragedy: After the girls vomit their meal, Alex slaughters them in the toilet; a Gay-Straight Alliance meeting seen at the start of the film is interrupted when one boy, checking on a bang at the door, is shot in the back; John escapes, finding his bewildered father waiting outside the school. Some violence is foregrounded, but most of it happens off camera; we catch sight of victims lying on the floor after they’ve been killed. The school is on fire, explosives detonate throughout the building, light ambient music plays. During the shooting, we hear crows in the distance, the gentle movement of water, birdsong, looping voices mixed with a low, doleful synth. “So foul and fair a day I have not seen,” Alex says to himself, quoting Macbeth, whose triumph on the battlefield is confused by a sudden storm raised by witches. “You know there’s others like us out there too,” Eric tells their principal before gunning him down. Moments later, while bragging about that kill, Alex shoots Eric in the chest, then corners a boyfriend and girlfriend in the school cafeteria freezer. Cuts of meat hang around them. The film ends with Alex teasing the students as they beg for their lives.

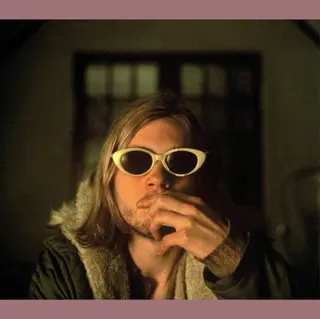

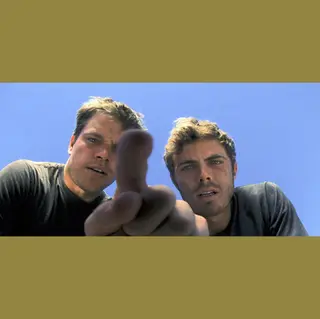

From left: Last Days, dir. Gus Van Sant, 2005; Gerry, dir. Gus Van Sant, 2002

Questions about why someone might decide to commit a mass killing propels almost every scene of the film. Early on, at the GSA meeting, one student asks, “Can you tell [if someone is gay]?” Of course, by the very nature of the film’s subject matter, the real question being asked is whether you can tell if someone is a shooter—something we all wonder about, despite the handiness of a composite profile for likely perps: conspiracy-minded single white males with a cache of assault rifles who are usually known about by family, community and police. So in 2003 the answers that Elephant grasps for are all too familiar when it forms a portrait of Alex and Eric as two loners who have never been kissed (and therefore, on the day of the shooting, they take a shower together and kiss for the first—and only—time). Are they homos or just lonely? Are they mentally ill? This was the scene that bothered me most at 16. At the time, I worried that Van Sant had unwittingly aided the right-wing conspiracies that portray gay people as disease-ridden harbingers of social ruin, occasionally prone to homicidal violence—Andrew Cunanan and Jeffrey Dahmer were two names known to Americans in fear of queer killers at the time.

From left: Alex Frost, Dany Wolf and Gus Van Sant on the set of Elephant

But the kiss is probably the most important element of the film in reckoning with why they kill—not to supply motive, but to acknowledge the heady confusions of a deeper, more violent lust that murder so often invites. It also bonds them. “The whole business of eroticism is to strike the inmost core of the living being, so that the heart stands still,” Georges Bataille argues in his 1957 book Eroticism. Eros is inextricable from death, he writes, that state by which our agonizing incompleteness finally achieves its yearned for completeness. Death “is the pathway into unknowable and incomprehensible continuity—that path is the secret of eroticism and eroticism alone can reveal it.” Alex and Eric’s shared kiss assents to fate as much as it admits desire; probably sex doesn’t have much to do with it. Rather, it consecrates the brutal act by which they intend to show the world who they believe they really are, drawing forth from their psychic turmoil the “real” Alex and Eric. They no longer resemble their classmates—a little shy, boredom-prone and lonely. Standing in the ruins of their boyhood, they have become avatars of the extreme violence that, until that day, had only privately fascinated them. This is the deformed, bloodstained image they project onto the world, what they finally see reflected in their classmates’ eyes: the monstrous power and horror of a broken inner life.