Liminal Cinema: Alice Rohrwacher

By Chiara Barzini

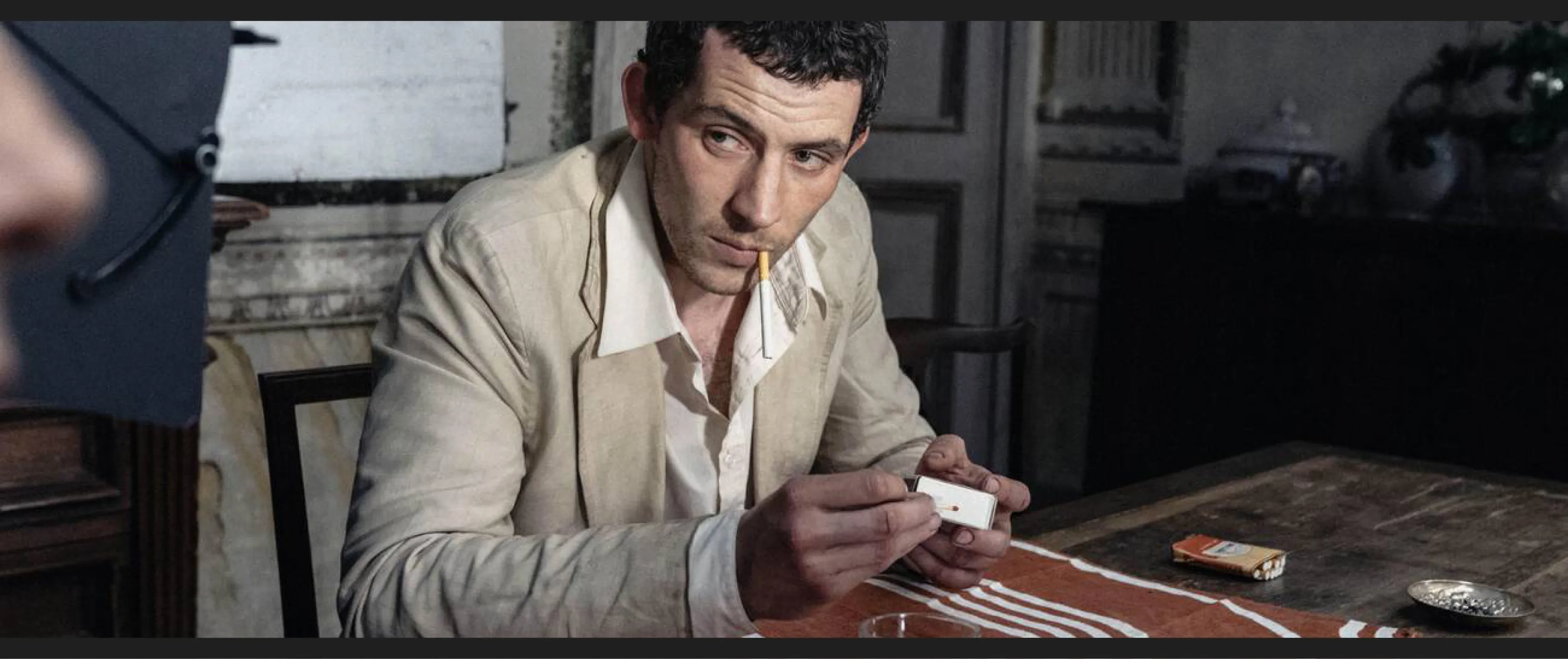

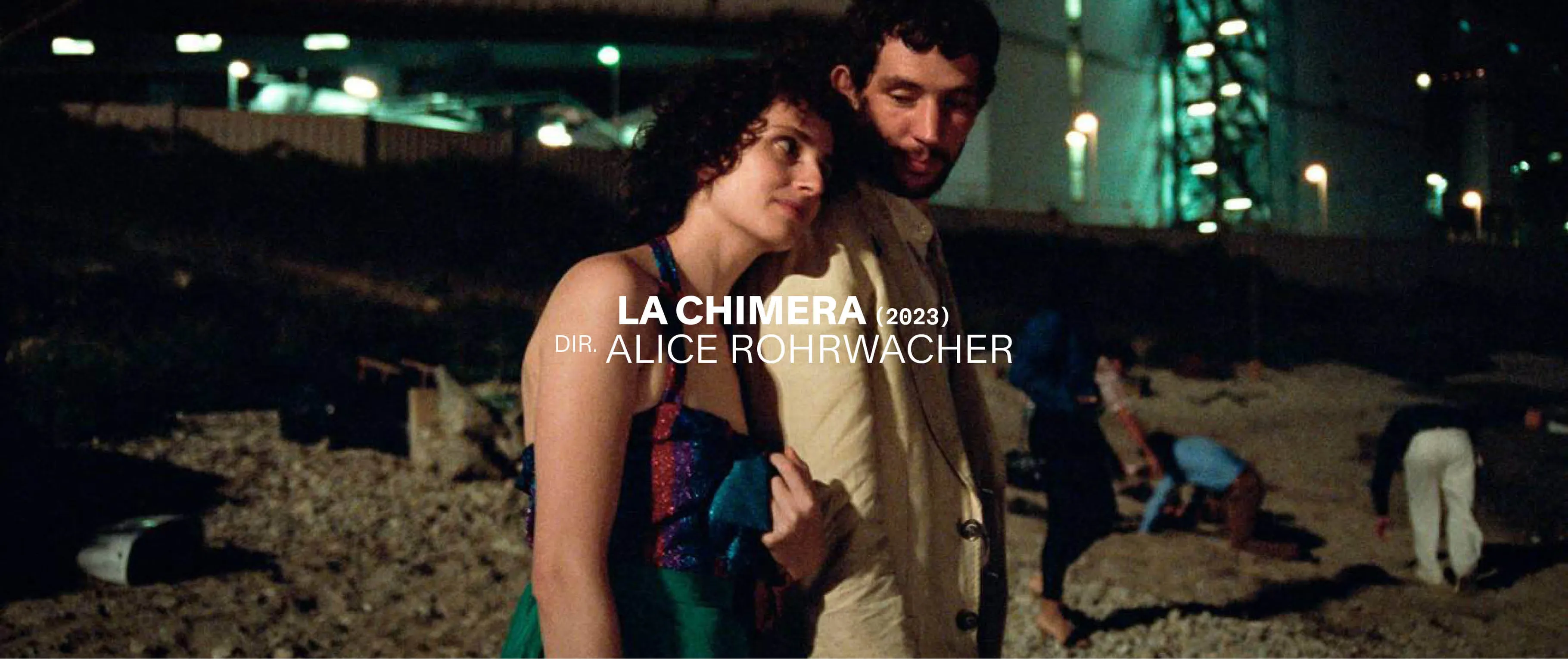

La chimera, dir. Alice Rohrwacher, 2023

Alice Rohrwacher’s Liminal Cinema

Chiara Barzini

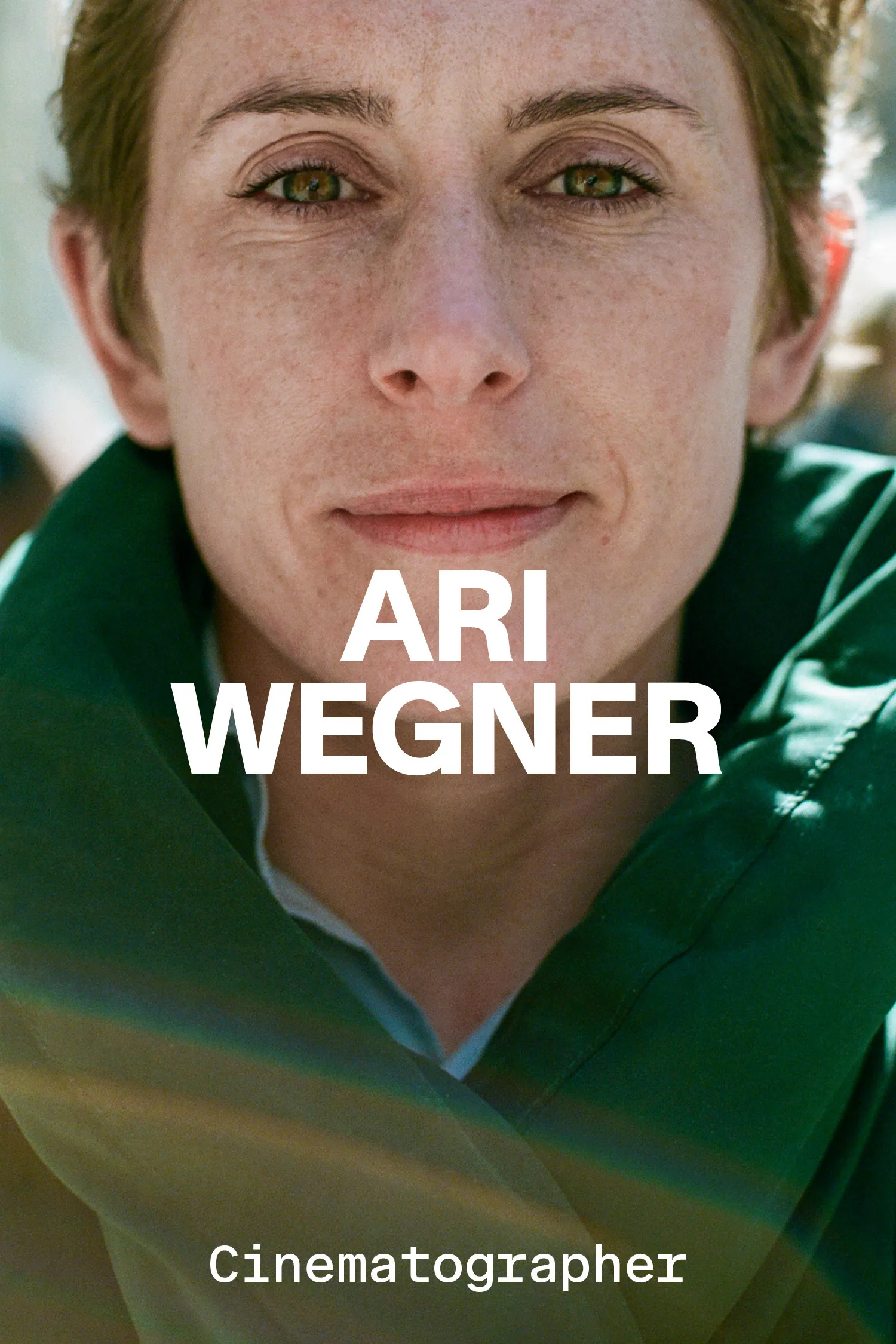

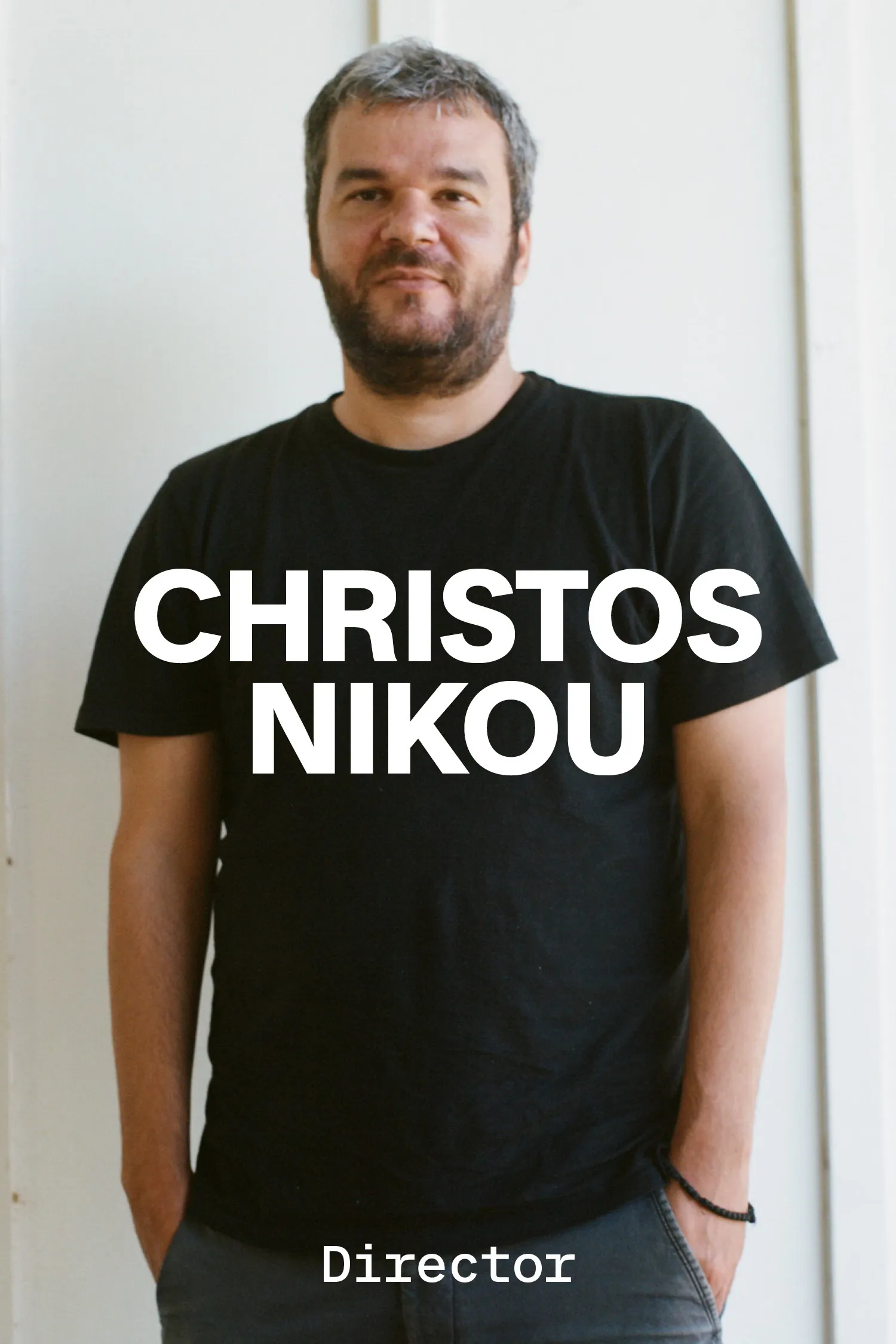

The filmmaker behind The Wonders and La chimera on old houses, historical artifacts and Josh O’Connor

May 5, 2024

In 2015 I was asked to moderate a conversation between Sofia Coppola and the sisters Alice and Alba Rohrwacher. Coppola had fallen in love with Alice’s second feature film, The Wonders (Le meraviglie, 2014), when she served as a juror at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival. Alice, then 33, wrote and directed the feature while her older sister, Alba, starred as Angelica, the matriarch of a large, complicated family of beekeepers in rural Umbria. Together with her eldest daughter, Gelsomina, Angelica tries to keep up with a rapidly changing world, alongside the family’s moody, idealistic, pseudo-hippie German patriarch, Wolfgang. The Wonders is a film about what it means to truly live in the countryside, but it’s also a fairy tale with a bitter lesson on capitalism. It went on to win the Grand Prix jury award at Cannes, catapulting Alice’s career onto the international stage. However, despite frequent offers, the director has kept her focus on her own ideas and scripts.

While The Wonders might seem overtly autobiographical—Alice also grew up on a bee farm with an eccentric German father—she has made it clear that she aims to go far beyond the confines of memoir or confessional fiction. Most of her films present a rural adolescence set against a world in flux. She investigates themes that divide generations and cultures. Lost dreams, specters of the past, messy families and landscapes themselves—their wild beauty and contradictions—are common elements in her starkly poetic work. In her third feature, Happy as Lazzaro, a young, kindhearted farmhand living in an isolated hamlet is thrust into the big city, where he becomes a fragment of a lost time unmoored in contemporary society. And Alice’s most recent film, 2023’s La chimera, starring Josh O’Connor, Carol Duarte, Isabella Rossellini and, once again, Alba, explores the savage yet magical realm of Etruscan-tomb raiders in the 1980s, who smuggled artwork and jewelry to sell on the black market, ancient treasures that would turn up in museums and private collections.

Today Alice still lives in the Umbrian countryside, north of Rome, where she grew up, and when she is not making movies she forages plants and works the land. We spoke again, this time over Zoom as she was taking a short break from screening La chimera at the local high school in Orvieto that she and her sister attended decades ago.

From left: The Wonders, dir. Alice Rohrwacher, 2014; Happy as Lazzaro, dir. Alice Rohrwacher, 2018

Are you excited to return to your old high school to present your latest film?

I am, but honestly I was afraid the kids would not be interested. I was surprised to find 300 students at the screening. I turned to them and asked, “Does anyone know who the tomb raiders were?” Nobody raised their hand, which was so shocking. I grew up in this area, and Etruscan tomb raiders were the protagonists of my youth.

I remember their presence very well. They were artful outlaws. They didn’t care if they were desecrating ancient Etruscan art. They created a huge black market in Italy in the second half of the 20th century.

Grave treasures were constantly looted 40 years ago. Tombaroli [“tomb robbers”] was an actual word, and I was so shocked to see those blank stares today. It means that no one is telling these kids anything. In every family there was a grave robber or someone who knew a grave robber. The fact that kids didn’t pick up on that history means they weren’t listening or paying attention to their history.

Does your daughter go to the high school where you screened the film?

She does, yes.

You and Alba did too. I remember Alba telling me those were some of her happiest years.

We grew up feeling so isolated until middle school, which made our initiation into Orvieto’s high school feel like we were entering a huge city. For us it was La Città. It was a big shock and a strong creative transition, too. I remember feeling overwhelmed and overjoyed. But perhaps for my daughter, who has already lived in so many places and had a glimpse of the world, this place might actually feel a bit tight.

The Wonders addresses this sense of isolation, the desire to break through and discover the world. The film started with a vision.

I guess it’s known as a mood board in cinema now, but at the time I didn’t really know what to call it. Maybe I thought of it as a collage. I work a lot with images that complement the words I write. They are a way to explain the vision beyond the narrative. I think a story is never just a story but an entire world, one that thrives on what is unspoken just as much as what is spoken. The original mood board for The Wonders comprised preexisting images, from archives or paintings. The pictorial element is always very important in all my films. In The Wonders I was inspired by the Italian Renaissance. In a script like The Wonders, it was crucial that I convey the light, the milieu, the space and mood of the world I was trying to evoke. So I actually made a booklet—which I no longer have, of course.

Oh, no! Where is it?

Who knows? Maybe at some point I’ll find it again. I’m not good at keeping things. I’m a person who creates and abandons. I’m a do-or-die person.

In 2023 you had a show at the Centre Pompidou, in Paris, a look at your work and a window onto your creative world. Was it hard to access your past material?

We managed, but I was initially worried because I had to find a lot of things that had been misplaced or lost. I don’t have anything anymore. It’s as if I need an empty space to be able to continue doing what I want to do.

David Lynch says you always have to go back to an initial idea or vision when you’re working on a film. You have to “ask the idea,” he says. Do you ever feel that you’ve lost your way in a film? If so, how do you find your way back?

It’s true, there is always a first image I need to go back to. In The Wonders it’s not so much the story of the family but of the actual house itself. My original inspiration came from a children’s book illustrated by Roberto Innocenti called Casa del tempo (The House). Every page of the book is a single frame of the same house as seen through the lens of passing time. We see humans inhabiting it, then leaving for unknown reasons. From a distance they resemble little animals. Other people move in and change the original idea of the house, giving it a different meaning. These layers of life show us something about the human condition: Each time we think our story is in some way the ultimate story, but it’s not.

A moment in time and not absolute history?

Yes, an intersection of time. From a very young age, I have lived in old houses where I felt I was experiencing something that had been experienced before. My story had to fit into a space that had originally been imagined and conjured by others. I could never imagine living in a space that might be built from scratch. I like to think that 100, 200, 1,000, 2,000 years ago, a girl might have been standing in my same spot, on my same street or hill. Maybe she even experienced my same turbulent emotions. The memory of past dramas is a great access point. I almost get the feeling I can travel in time. I wanted to transport this emotion in my films.

“My spaceship is always the house where I live, where I feel like a passing entity.”

In The Wonders the house is a historical container but also a receptacle for ego, pain, idealism, dreams and disappointment.

In the film the characters live everything with a great pathos and intensity in a place that was there before them and will be there after. I liked this idea of being able to simultaneously have an internal and external point of view. A point of view of Earth as seen from the moon, in a way.

So you’re always moving to new homes that have had long lives before you?

My spaceship is always the house where I live, where I feel like a passing entity. This transitory feeling of passing through is big for me. It’s strongly opposed to the basic idea of capitalism, which is to preserve heritage, to own, to stay and be rooted.

Capitalism flirts with the illusion of stopping time. The tourism industry takes over ancient monuments and makes them static.

To be able to sell something, you have to pick out only one layer of that thing, you have to flatten it. Otherwise it doesn’t fit on the shelf. Selling an idea of antiquity always humiliates and trivializes the deeper sense of history. It’s like when you renovate an old house and decide to erase all its history and maybe keep just one layer as the key to interpreting the place. The strength of places lies precisely in the fact that they are complex and brimming with history. Complexity is precious—it should be cherished and included in the conversation.

It seems you tackle the idea of tradition with the same attitude. The family in The Wonders hangs on to an old way of doing things in their rural area, but their ideas of tradition and necessary rules begin to falter, thanks to Gelsomina’s need to venture out.

I wanted to ask the question, What does tradition mean? Tradition is always the latest incarnation of a process. It is not something definitive. It is not printed, defined. And so I wanted to tell the story of a family that is traditional, but in a non-canonical way. When the television world invades the territory in search of “traditional family,” they are unable to be a perfect match. Gelsomina’s family cannot find their place in advertising and communication. They don’t know how to sell themselves. This theme, I think, affects everything I do. I feel that I have a very clear sense of what I want to do—my path is crystal clear—but it is very difficult to place, to sell.

We are dealing with choices made in the 1970s by a generation that was certainly wondering how to change the world.

Yes, and maybe their way of changing the world meant giving up institutions and creating microcosms. Many people who decided to break away from institutions and create alternative structures grew their children within these isolated worlds. Now that I’m an adult, I think it was a beautiful choice, a possibility to question the present and not take it for granted. The parents in the film made questioning their entire life’s work. Maybe that’s the biggest legacy for me, to make life and work be the same thing. To not separate these two worlds.

It is clear, however, that Gelsomina has to be able to break away from this family in order to return to it. What does she learn on a philosophical level?

She needs to see her family as a net, not one that towers above her but a safety net she can fall onto when she needs to. My wish for her is to see it as the net of the acrobat. The net that is underneath you and can protect you from falling, not the one that prevents you from flying.

From left: Maria Alexandra Lungu in The Wonders; Luca Chikovani and Adriano Tardiolo in Happy as Lazzaro

If Casa del tempo was the starting image for The Wonders, then what was the one for La chimera?

A desecrated landscape where tomb raiders could move freely. The idea was to tell the story of the grave robbers not as exceptions, as predators or black sheep doing bad deeds against a bright and just society, but as children of a culture that sees economic success and easy money as the only real possibility for emancipation. A culture that no longer has respect for anything, a world where forests are full of garbage, coal-fired power plants are built over holy sites, and the sea is full of garbage and sewage. Certainly another very strong image was that of the broken ancient statue. When I spoke to grave robbers, they often told me that in order to move particularly large pieces away from the tombs, they occasionally had to break them. And so I immediately envisioned a statue of a woman’s body, a nature goddess broken by these human beings from a future world.

I imagine it wasn’t easy to manage a large cast always on the move. Was it more joy than sorrow?

I always remember the joy more than the sorrow, but I’m constitutionally like that. I often forget pain. I was working with a large cast of actors, nonactors and foreign actors. I had to communicate something that was so rooted in Italy’s cultural identity to Josh O’Connor and Carol Duarte and really felt a great responsibility on my shoulders. Also, there’s the fact that the film doesn’t follow a single story but is a tapestry with many threads. There were times when I had the feeling that my hands were full of threads and they were all running away from me and I had to go back and hold on to them one at a time. Another practical difficulty was to create art objects that would exude an actual aura onscreen. Objects are in a sense the protagonists of the film, and I was afraid that we wouldn’t manage to make something that would contain real mystery or that they would look like obvious replicas. Emita Frigato and Rachele Meliadò are incredible set designers. With meticulous care, they re-created the entire Etruscan path of creation. Then, one day, walking around the city of Orvieto, I ran into the great Etruscologist Giuseppe Maria Della Fina. I told him we were trying to reconstruct a sacred Etruscan statue, and he gave me the key: “Why copy? Why don’t you invent the statue? After all, there is still so much to discover about Etruscans that anything is possible.” So we decided to invent the piece from scratch with the help of Fabian Negrin, a children’s book illustrator with great imagination. Thus the Goddess was born.

You and Josh O’Connor posted a video online to ask for the audiences to push theaters to keep showing the film. And it worked! Can you tell me something about your work with him? How did you find each other? What kind of creative spark did he ignite in you?

The connection with Josh O’Connor is a great one because it came from the flight of the birds, as the Etruscans would say—meaning, from destiny. I hadn’t thought of him at first. I was looking for a much older actor. I imagined Arthur as someone in his sixties wandering around the lands of Tarquinia. Then, at some point, a letter came in from Josh, and this made me really want to meet him. Getting to know him was like meeting a soulmate—at least artistically speaking. His enthusiasm, his generosity, his humility and grace make him a man who lives outside the realm of time. The work we did together united us. I hope we will work together forever. Josh has done a very good job with a difficult character. To be both gruff and sweet, closed in but also ridiculous. He’s a romantic hero in a world that no longer has anything romantic about it.

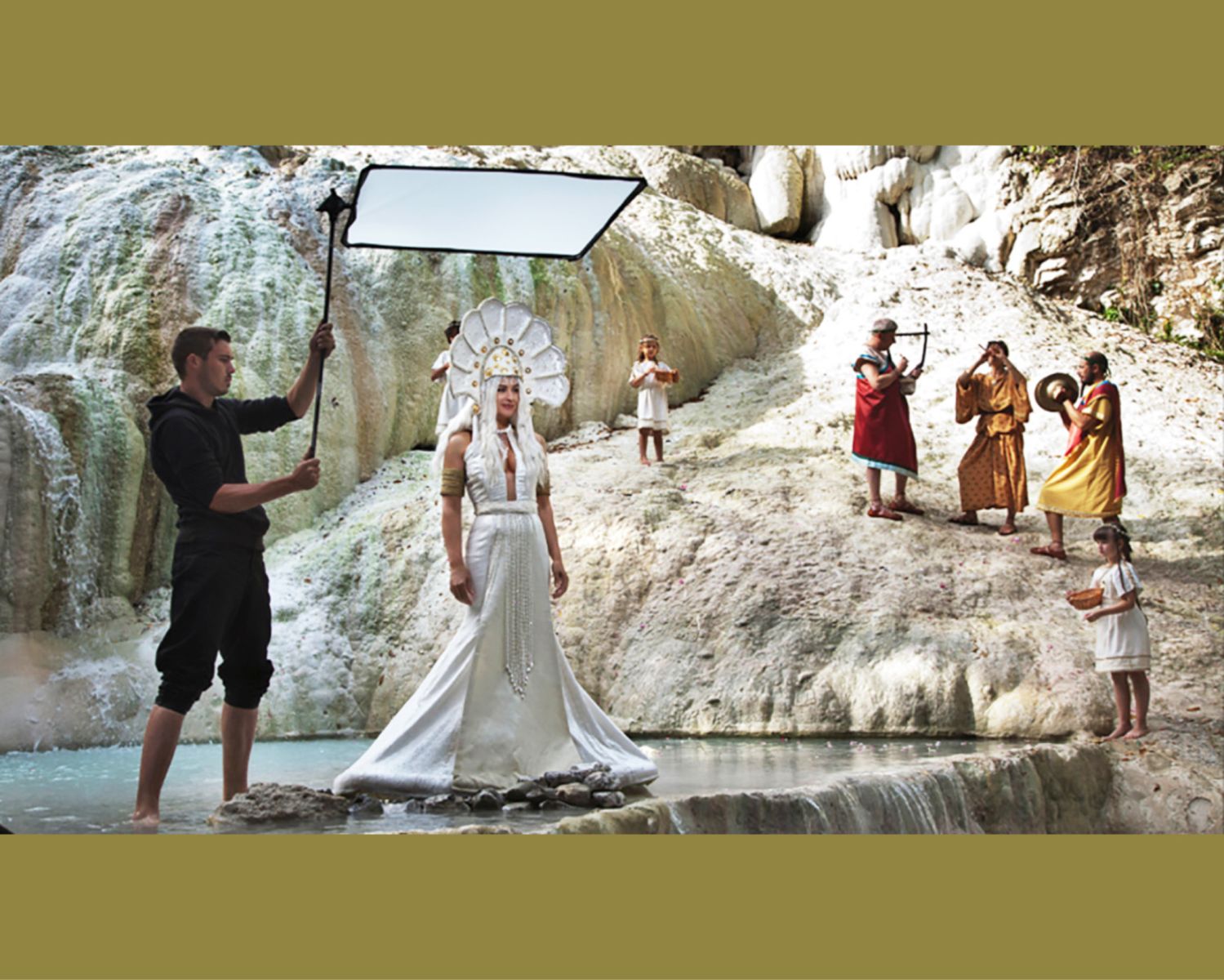

Monica Bellucci (in white) in The Wonders