May Day

By Boris Bergmann

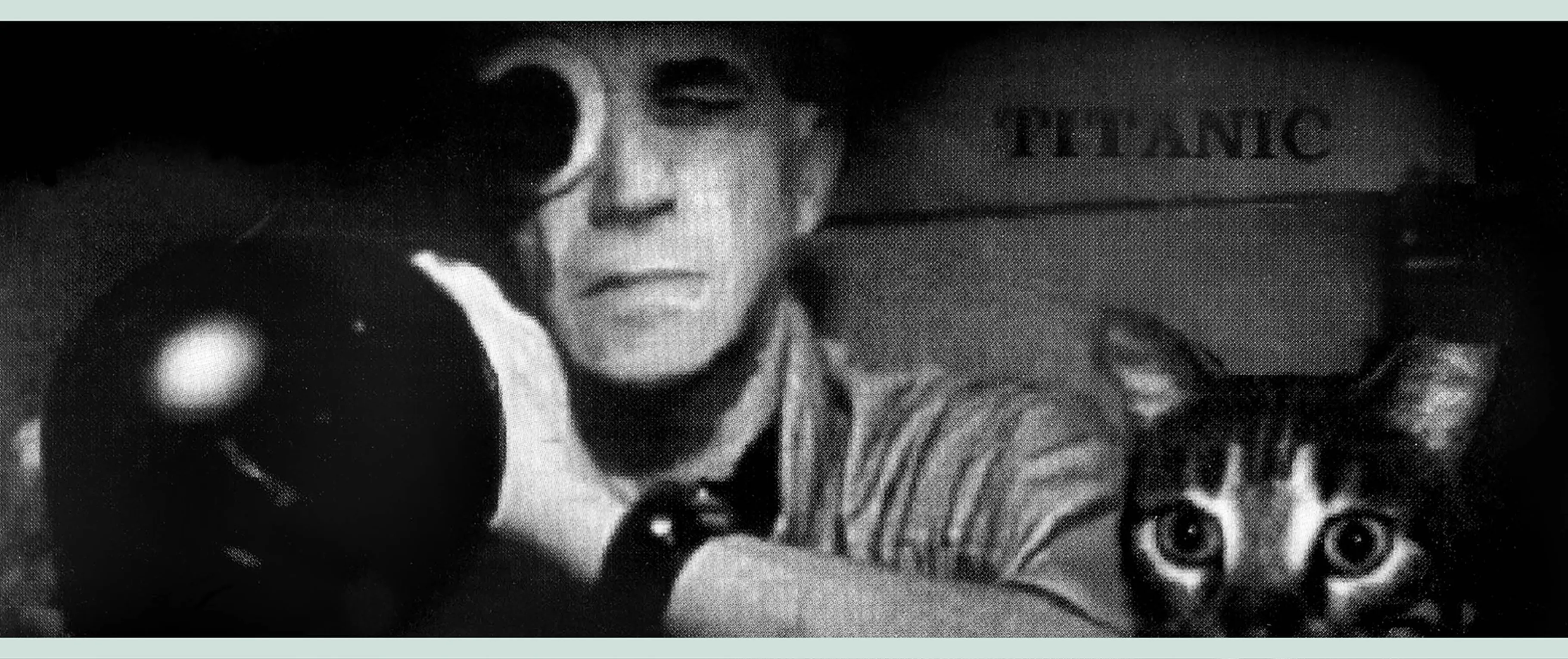

Le joli mai, dirs. Chris Marker (pictured) and Pierre Lhomme, 1963

May Day

Sixty years after documenting class conflicts on the streets of Paris, Le joli mai remains radical cinema

By Boris Bergmann

November 8, 2023

There’s something disarmingly simple about the project of Le joli mai (The Lovely Month of May). An almost childlike simplicity. It has one central subject: city life. One set: Paris in the early 1960s. The spring of 1962, to be exact, renamed “the first spring of peace” after the Évian Accords, a set of treaties with Algeria to put an end to eight years of France’s last colonial war. The documentary takes as its chief material the free speech of citizens on the Paris streets. The goal was reality in its purest form, shot with the very recent invention of a portable handheld camera.

From left: filmmaker and cinematographer Pierre Lhomme; Paris as the backdrop for Le joli mai

If a camera were to capture the free opinions of Parisians on the streets today, the topics covered would be practically unchanged: social and racial tensions, the omnipresence of money, postcolonial views, the sitting government’s vast urban projects to alter the face of the city, the temptation of middle-class comforts versus larger global concerns. Six decades of social upheaval in the French capital have done little to alter the preoccupations and concerns of its everyday citizenry.

Perhaps the more interesting question of this theoretical update is not what topics would be covered but how these clips of everyday street life would be filmed. Director Romain Gavras, for example, might use drones to capture the recent violent confrontations between suburban youth and police officers. Justine Triet, the 2023 winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes, might blend a family drama into a tale of a political election on the Left Bank. Leos Carax might follow a homeless person to reveal the poetic life in the capital from its depths. Certainly, each contemporary director would have their own intimate, idiosyncratic point of view. But they would all owe a debt to Le joli mai’s fearless directors, Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme, who attempted to tackle reality head-on, without any special tricks or interference. And the how of their filmmaking is no less revolutionary: in the early 1960s, wielding a camera and microphone through the streets was something of a shock. Because of this experimental daring, the film managed to give voice to the people of Paris, unfiltered and unvarnished like never before.

The methodology was straightforward. For the duration of the 165-minute, black-and-white film, Parisians are stopped in their tracks, at first astonished by the directness of the directors’ questions about their happiness, their hopes, their fears, their dreams. The frankness is sometimes taken as provocation. But the passersby quickly acclimate to the spirit of the exchange. They soon forget the camera, the microphone. They forget that they are being recorded. They have never been given the chance to speak their minds in this way. Their souls have never been probed. This is what Marker and Lhomme intend. The filmmakers have chosen essential epicenters of modern life to conduct these surprise interrogations: the Paris Bourse (the Paris stock exchange), factories, the new grands ensembles (large housing projects constructed in the suburbs, mostly by the disciples of Le Corbusier), bourgeois salons. By showing the marginalized and giving them a central focus, Lhomme and Marker reveal the city’s true landscape of exploitation and alienation.

Le joli mai was the first and only time the duo worked together. Marker had already directed several films, primarily documentaries inspired by his travels in Cuba or in Russia. Lhomme was a young but well-respected director of photography. They make a great pair, and there’s a sense of cleverness and joy in the vast composite of locals they choose as subjects: a bartender from a working-class neighborhood, an Algerian immigrant, a young engaged couple, dancers in an anonymous nightclub, a mother from the suburbs, a student from Africa, three girls from a posh district of Paris, an architect who just designed a new housing project. You never see Marker’s or Lhomme’s face; sometimes you only hear a voice.

The film’s innovative filmmaking was actually made possible by a cinematic forerunner that serves as a cinematic older brother to Le joli mai. Two years earlier, in 1961, directors Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin released a political documentary, Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer), which asked French people the question “Are you happy?” (before ultimately veering into a film about a Parisian Holocaust survivor). Rouch was a consummate pro at anthropological documentaries by the time he hit the boulevards of Paris in 1960 for this assignment. In order to make Chronique, he and his film crew invented their own portable camera, much lighter and compact than previous versions: a 16mm combined with a tape recorder. That breakthrough allowed Le joli mai to capture the frenetic, off-the-cuff aesthetic that mimics the life of the busy streets.

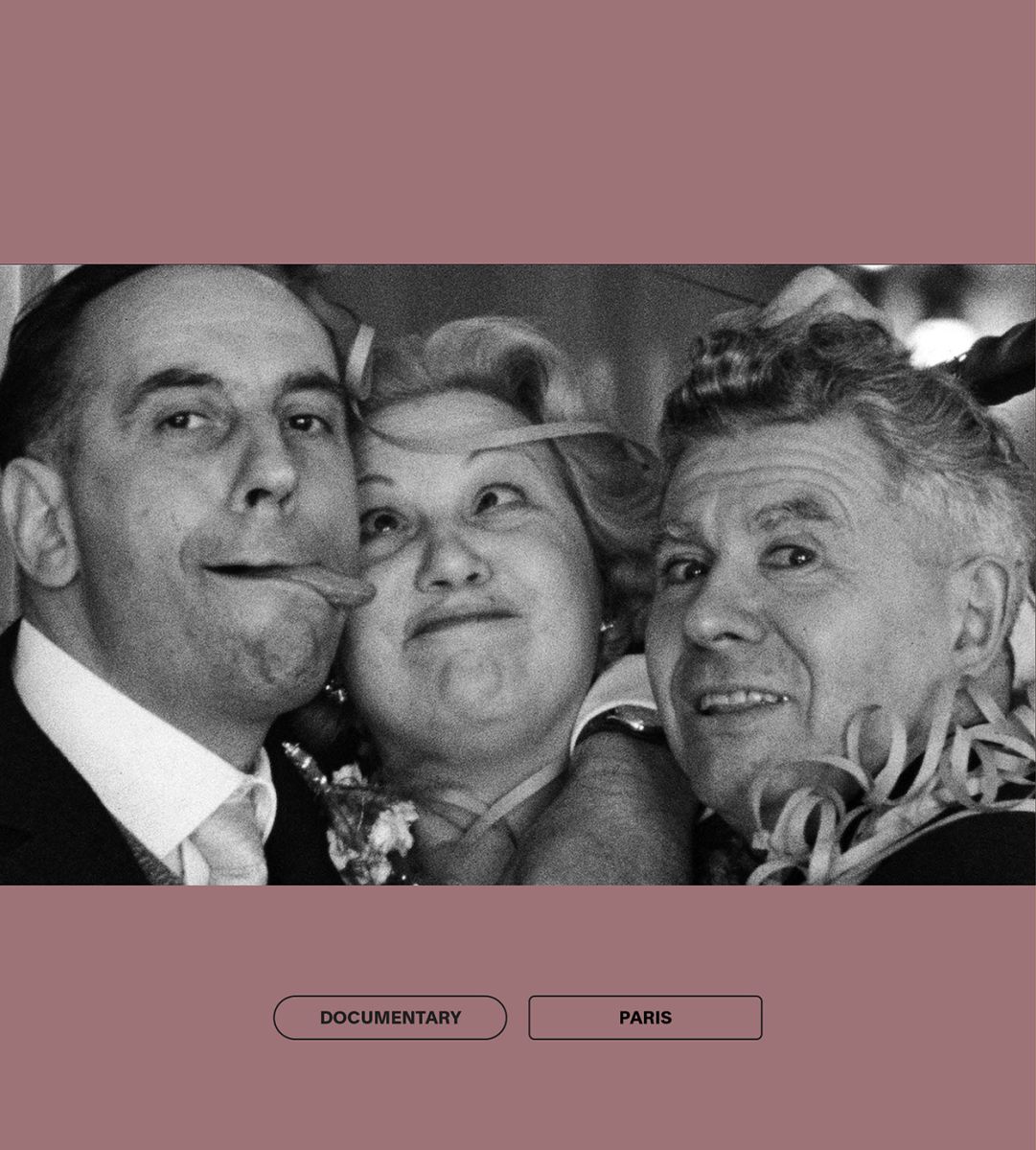

Revelers in Le joli mai

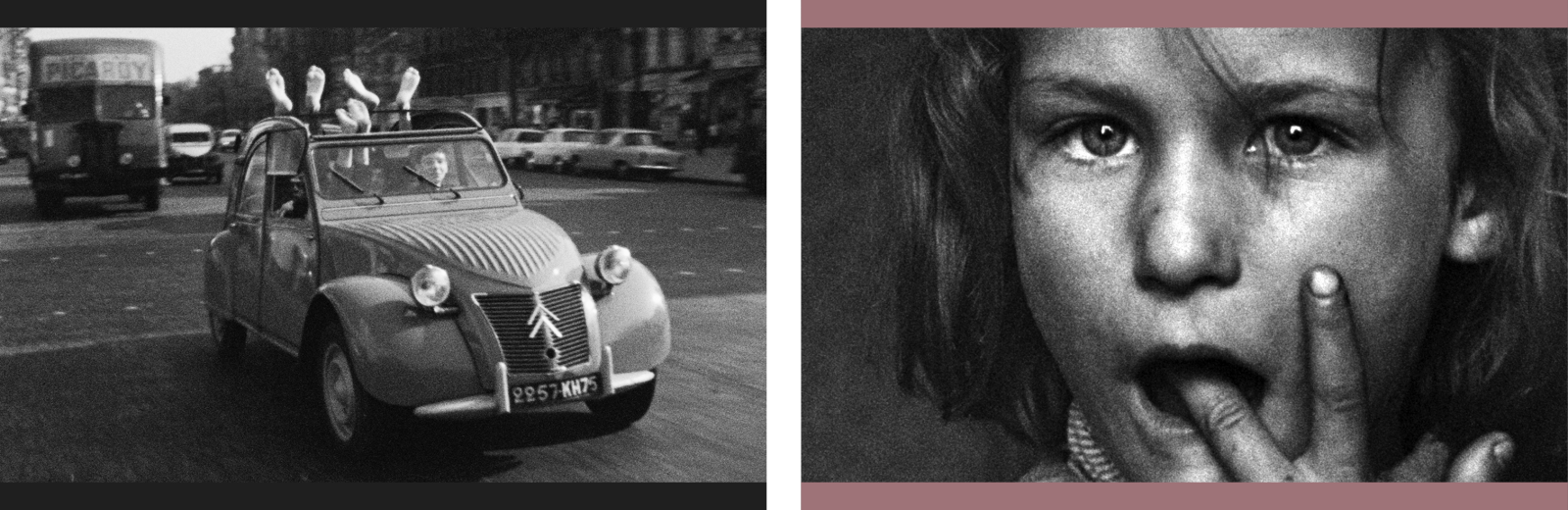

Le joli mai, however, moves out of Chronique’s shadow, primarily through its artistry and evocative editing style, a signature of Marker’s work. Such idiosyncratic editing was, in the filmmaker’s own words, a way to put a “gaze on another gaze,” as well as allowing the scenes to live and breathe in a continuous present without any flashing backward or forward in narrative time. Instead, Marker allows his camera to capture offbeat details that would typically have been fodder for the cutting-room floor: close-ups of scared cats in cages while two engineers debate the place of new technologies in people’s lives, or a spider crawling across the shirt and jacket of an interviewee. A scene outside a court trial, another residue of the Algerian War, is directly followed by the image of a dancefloor, as if to signal how the population tries to forget its darkest thoughts by indulging in the city’s decadent nightlife.

Fundamentally, the ambition of Le joli mai is to capture the fissures and attitudes of a rapidly shifting French postwar society: the transition from an archaic Paris—epitomized in the film by the city’s famous rue Mouffetard, a medieval street home to a traditional farmers market—to its triumphant modernity, with its massive urbanization of high-rises and public housing projects. Faced with this moment of seismic social change, Lhomme and Marker respond with a cinema that makes a diagnosis. They want to show the nooks and crannies of a pivotal era, of a “seasonal disorder,” as critic Sam Di Iorio wrote during the 2018 Marker exhibition held by the Cinémathèque Française, the largest film archive in France.

In the opening scene of the film, a young suit salesman explains the key to the good life: money. “The more money I bring home, the more my wife is happy.…” On the other hand, a completely different reality slowly emerges: the consequences of the Algerian War, which in 1962 the French government was still calling a “law and order operation” and which the film’s passersby seem ready to forget. When Marker and Lhomme ask an old man his thoughts on the trial verdict for a failed coup d’état intended to force President Charles de Gaulle not to abandon French Algeria, his answer is immediate: “I think as our generals were sentenced to death they should be executed, but also the Algerians who killed our men.”

The shadow of progress is money. The shadow of self-proclaimed “law and order” is war. This contradiction at the root of French society continues to this day. In Le joli mai, Lhomme and Marker have captured the heartbreaking tug-of-war between blind bourgeois bliss and the desire for radical change. Six years before the revolution of May ’68, and 60 years before the police riots that ignited the French suburbs last summer, Lhomme and Marker’s documentary is prophetic. It reveals the guilty, materialistic subconscious of a nation.

This is cinema for the people, and even by the people. Notably, the film’s epigraph turns Stendhal’s famous line in The Charterhouse of Parma (1839)—“To the happy few”—on its head. Stendhal meant that his audience was restricted, elitist. Marker and Lhomme prefer to offer their film to as many as possible. Their epigraph is unequivocal: “To the happy many.”

Marker would soon go even further, from 1967 to 1974, supplying cameras to workers from factories in Sochaux and Besançon, the industrial area of France, so they could tell the story of their struggle “by their own means.” This audiovisual social experiment, called Groupe Medvedkine, eventually took the form of a series of short films made by the workers themselves. From Le joli mai onward, Marker aspired to show the marginalized figures of the system: students, workers, women, militants and immigrants. He gave voice to the unheard and focused on the rejected. Rejected from what? From the official Parisian vision, the dominant image perpetrated by films like The Great Escape and Lawrence of Arabia, two of the biggest box-office draws in France the year Le joli mai was released. Instead, Lhomme and Marker refuse the status quo idolatry that goes with those kinds of movies. They prefer cinema vérité, real images populated by real people—an egalitarian cinema (albeit with a voiceover narration by Yves Montand, a well-known actor who was at the time also a committed Communist; popular French actress Simone Signoret voiced the English-language version).

“Six years before the revolution of May ’68, and 60 years before the police riots that ignited the French suburbs last summer, Lhomme and Marker’s cinema is prophetic. It reveals the guilty, materialistic subconscious of a nation.”

After the film’s release, the filmmakers attempted to alter the term cinéma vérité because of its heavy-handedness and deliberately messianic scope. They preferred “cinéma direct,” originally coined by the Italian director Mario Ruspoli. Nevertheless, Le joli mai lives on as a classic of cinema-vérité experimentation.

Decades later, when the film was restored and released on DVD for the first time, Lhomme confessed that hours of rushes were never shown. Pieces of truth lost forever. A whole section of Le joli mai had been forgotten, including a day of shooting in the back of a cab while interviewing the driver and his clients. But thanks to the directors and the freedom they give their subjects, we are left with enough of what was and is. Present-day France, in the throes of yet another moment of societal change, could do well to imagine a sequel.

Scenes from Le joli mai