Panic Attack

By Brian Alessandro

The Holy Mountain, dir. Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973

panic attack

The radical art movement behind Alejandro Jodorowsky’s trippy 1970s masterpiece

By Brian Alessandro

June 17, 2024

“Panic always appears as the announcement of spiritual birth,” said Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky. “Human beings who have been relegated to the lowest rank of the spirit, that of ‘spectators,’ men who do not really partake of existence, but think or wish to ‘know’ it without having to move from their seats.”

![]()

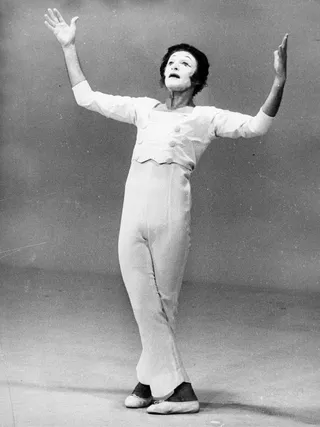

French mime Marcel Marceau

![]()

In one climactic scene ofJodorowsky’s 1973 hallucinogenic cult masterpiece The Holy Mountain, a Christlike figure enters a cave, dagger in hand, pursuing an elusive spiritual radiance. Antagonized by the light’s mystery, he slashes at it, exposing the illumination as a fraud, mere paper. What lies behind it is a rainbow-colored room inhabited by an alchemist wearing a white robe and wizard hat, sitting on a throne made of goats. Real goats.

The Holy Mountain is less a cohesive narrative than an interminable succession of bizarre, destabilizing and inexplicable images designed to overwhelm its audience. In the film, the Christlike figure and the alchemist embark on a journey on which they will scale a holy mountain to meet with the nine immortal masters to unlock the secret of eternal life. The film proves the ultimate example of its mischievous director’s intention to jostle complacent, apathetic viewers out of their passivity, instead eliciting a visceral experience that would revolutionize the entire relationship between audience and screen. Other spellbinding, lunatic scenes in the two-hour surrealist quest include a man lying naked under a bed of tarantulas; gaudily ornamented horned lizards assuming the roles of Aztecs and Spanish conquistadors before being blown to smithereens; and the castration of a young man sacrificing himself to Neptune’s “sanctuary of 1,000 testicles.” But such mind-melting imagery didn’t crop up from nowhere. The Panic Movement had been underway for more than a decade.

Hallucinatory imagery from The Holy Mountain

“It was an art intent on breaking its own frame.”

Guided equally by Samuel Beckett’s Theatre of the Absurd and Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, Jodorowsky, along with playwright and filmmaker Fernando Arrabal, and cartoonist and writer Roland Topor, founded the movement in Paris in 1962. Jodorowsky had been in Paris studying the art of miming with Marcel Marceau and working on a production for French entertainer Maurice Chevalier. Named after Pan, the god of the wild, the Panic Movement sought to inspire shock, engender chaos, and disrupt peace. Most curiously, the group took aim at surrealism’s mainstream popularity, seeking to restore it to the fringes by alienating squeamish bourgeois tastes. Teatro pánico, a manifesto written by Jodorowsky in 1965, outlined the movement’s tenets, central to which were euphoria, humor and terror. “Toward the ephemeral panic or getting the theater out of the theater!” wrote Jodorowsky. It was an art intent on breaking its own frame.

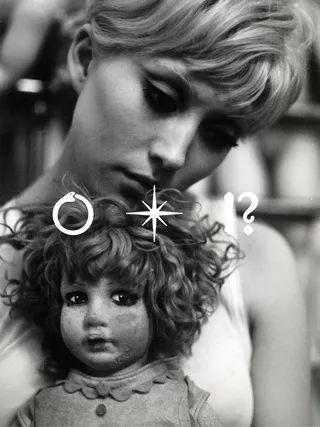

The Panic Movement began with shock-theater works and “happenings”—largely improvised scenarios fostering an environment of unrest and likely inspired by performance artist Allan Kaprow in the late 1950s—and were staged primarily in Mexico in the 1960s upon Jodorowsky’s return from Paris. Scenarios included a nude woman doused in honey and a man being consumed by an enormous plastic vagina, which he chops through with an ax. Jodorowsky appeared in many of these happenings, alongside various artists, musicians, actors, poets, dancers and prostitutes; he compared participating in these projects to electroshock therapy. Soon, Jodorowsky moved from theater to film, creating his 1968 surrealist black-and-white feature Fando y Lis (so disturbing it caused a riot when it was released and was subsequently banned in Mexico) and the 1970 cult acid-Western El Topo. It was the wild decadence of The Holy Mountain, though, that solidified Jodorowsky’s reputation as a kind of bad-boy mystical surrealist (one that continues to see him having retrospectives in major art institutions to this day), helped along by some influential supporters. Both John Lennon and George Harrison were fans of El Topo, and the Beatles’ manager Allen Klein produced The Holy Mountain, with Lennon and Yoko Ono providing $750,000 for production. The film was shot sequentially in Mexico in 1972. Before production commenced, the principal actors dedicated themselves to three months of Zen, Sufi, and yogic exercises under the guidance of Bolivian philosopher Oscar Ichazo, who also encouraged Jodorowsky to take LSD for the sake of spiritual expansion. Jodorowsky gave his actors psilocybin mushrooms during filming.

![]()

Fando y Lis, dir. Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1968

![]()

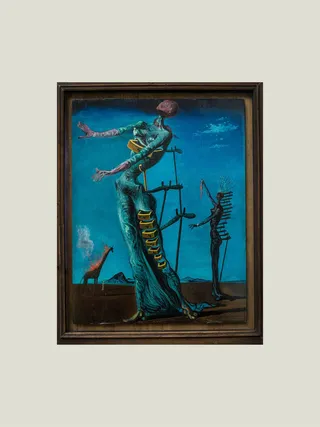

Burning Giraffe by Salvador Dalí, circa 1937

When The Holy Mountain first screened at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1973, and later premiered at New York’s Waverly Theater as a midnight movie that November, the film enraged critics, particularly in its treatment of animals. The film features untold cruelties to animals, among them a parade of skinned sheep, a carved-out bull carcass (in which a character takes a bath) and an eviscerated octopus. This kind of macabre imagery came right out of the Panic Movement playbook, which often showcased animal suffering for a heightened effect. Some of the movement’s early live performances featured the crucifixion of chickens, the cutting of geese throats, the taping of snakes to Jodorowsky’s chest as he is stripped and whipped, and the tossing of live turtles into the audience. Clearly, this was all done before the rise of PETA and animal-cruelty laws. In a January 1974 New York Times column on the mistreatment of animals in The Holy Mountain, critic T.E.D. Klein noted the “curious—and alarming—trend in filmmaking…. What can only be called Death for Art’s Sake.”

Out of step with mainstream ethics (or rather, anti-mainstream in all senses of the definition), The Holy Mountain uses the grotesque as a cudgel to smash artistic expectations, the absurd as a tool to dismantle social constructions and the iconoclastic to illuminate the limits of the divine. The story itself of a stymied search for answers is based on the 16th-century autobiographical text Ascent of Mount Carmel by John of the Cross and 1952’s allegorical novel Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing by René Daumal. The film seeks access to the sublime even while lampooning the search and mocking its discoveries.

The Holy Mountain

In the end, the illusion is shattered as the search is revealed to be a sham. Addressing the audience, the alchemist (played by Jodorowsky) instructs viewers to leave the holy mountain, as “real life awaits us.” All that came before this Brechtian moment—nearly the entirety of the film, save for this final minute—was a mere charade, a metaphor for how people are fooled by their own materialistic fixations. The truth of existence can only be found in death, it seems, by “surrendering the faithful animal [we] call [our] body,” as the alchemist says to the planets. “For it was only a loan.” Meanwhile, life seems to be a jumble of confusion and insanity, all of it very beautiful to look at.

The Holy Mountain would prove Jodorowsky’s final attempt to move the Panic Movement toward cinema before it was dissolved by the director himself in 1973. However its influence lives on. Just as Jodorowsky’s took inspiration from the films of Luis Buñuel and Jean-Luc Godard, and the art work of Salvador Dalí, it’s possible to see such neo-surrealist filmmakers as David Lynch and Nicolas Winding Refn as artistic disciples (Refn thanked Jodorowsky in the closing credits of his 2011 film Drive.). Maybe future directors will continue to be inspired to find intrepid ways to re-sensitize their audiences.

![]()

Intermission during a production of Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

![]()

El Topo, dir. Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970