Paradise Lost and Found

By Chris Wallace

Soy Cuba (I Am Cuba), dir. Mikhail Kalatozov, 1964

PARADISE LOST AND FOUND

Avant-garde propaganda film Soy Cuba (I Am Cuba) endures as a masterful cinematographic portrait of revolutionary national character

By Chris Wallace

January 8, 2024

If a romantic white-man-as-savior genre runs through the 20th-century history of literature and cinema, it might be most observable in stories of exotic travel. In those stories, a (generally) white male from the global North travels to a (perhaps postcolonial) place of civic and political unrest in order to find himself, make his name or save the dame. With that archetype in mind, the 1964 black-and-white film Soy Cuba (I Am Cuba), neither produced nor directed by members of the capitalist West, might best be understood as the response—or, at the least, one country’s blistering retort.

Soy Cuba trailer

In four discrete sections that each play like a one-act morality tale, the film lays out the full fantasia that books and film so often projects on the tropics, and it reads it back like an indictment of the Western gaze. Funded and produced as unabashed propaganda in a joint effort by the Soviet Mosfilm and the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos, Soy Cuba was provided with an enormous store of resources and some of the best film talent Russia had to offer. The 14-month shooting schedule followed on the heels of the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban missile crisis. Purportedly, Fidel Castro went on set to watch the rushes. But if the film was intended to justify and valorize the recent revolution in Cuba, it proved a fantastic failure, bombing both commercially and critically in its two sponsor countries upon release—and then not making it to many screens elsewhere for 30 years. By the time it did make it to a wider release, and was eventually shown at the Cannes Film Festival in 2003 (partly by way of Martin Scorsese’s championship), Soy Cuba was already the stuff of underground, bootleg legend, lauded by film nerds as one of the most beautiful films ever made.

The film’s director, Mikhail Kalatozov, who’d won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1958 for his film The Cranes Are Flying, began his career as a cinematographer. The opening titles of Soy Cuba, shot on infrared film from a floating, dreamy aerial perspective, immediately call to mind the kind of images taken from contemporary spy planes. But Kalatozov is entering the viewer into a kind of dream state, not a war zone. His Cuba is a surreal Eden, where the nodding palm trees are a brilliant white and the gentle Caribbean coves shimmer a cool black. A brief, intermittent voice narration informs us that Christopher Columbus, on arriving at these shores, called it the most beautiful place ever seen by human eyes. Already we are in the thick of colonialism and paradise lost when we arrive at a rooftop pool party that’s in full swing. This is the Havana of the Batista era, a libidinous playground for the jet set and a nonstop casino for Western industrialists. But cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky (who also worked on The Cranes Are Flying) uses a wide-angle lens, inserting us into the scene as if we are unwelcome ghosts sneaking into this psychedelic Goldfinger-era pool party. Still in a dream state (or a psychedelic state), the camera begins to do things, impossible things: climbing up the sides of the building, going into the pool underwater and then out again, whipping through the dancing and grooving in one continuous long take—looking more like, say, the opening party sequence of 2022’s Babylon than anything mid-century. Kalatozov’s marvels have only just begun.

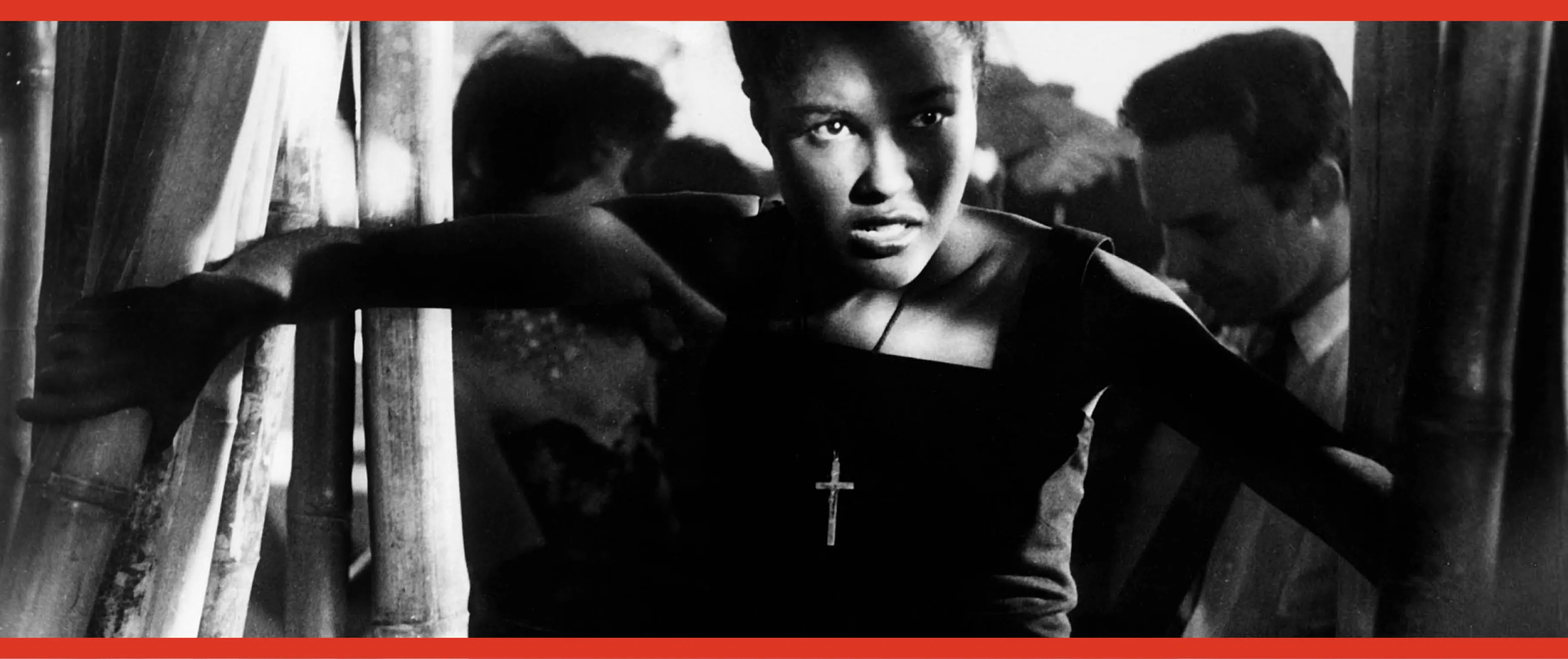

Stills from Soy Cuba

The first of the four stories follows a good Catholic girl, Maria, who by night is forced into prostitution by the American casino-going crowd. The ruin and the poverty in which she lives is cast as the other side of the jet-set coin: “Do you still love me now?” another sudden burst of narration asks. “I, too, am Cuba,” the film pronounces, over images of Maria’s shantytown.

The second section concentrates on Pedro, a proud and upstanding tenant farmer. When the United Fruit Company buys the land and evicts him and his family, he burns the lot to the ground and dies in the process. The daytime fire that consumes Pedro’s home and his paradisiacal cane fields is again shot on Urusevsky’s infrared, making for something completely otherworldly, an unbearably beautiful destruction. But it is the extreme angles and dizzying intensity the director creates with canted frames and crane shots that follow Pedro into his delirium, taking on his frenzy, that introduce us to something near to a subjective frame. We have gone from the POV of the ghostly visitor at the party and the shanty to something like a close third-person-subjective viewpoint with Pedro in all of his justified rage.

The third sequence, about activists at the university who are martyred at the hands of Cuban president Fulgencio Batista’s troops, diffuses perspective again. It features one of the most famous single-take tracking shots in all of film, following a funeral procession down a street, then up the side of a building several stories, glides from a rooftop into a cigar-rolling factory, and then out the window, where it flies down the street above the cortege. We have now become something like the Cuban spirit, the spirit of the revolution, looking down on the action from another floating, dreamy aerial view. And even though by this point in the film the technological wizardry, as well as the heavy-handedness of its messaging, might risk deadening the viewer, the shot is still mind-boggling and powerful.

“…In a cinematic history obsessed with the individual, the main character, the star holding the movie together, has been deleted.”

Shooting Soy Cuba, 1963

Our gaze widened when we reach the fourth sequence, which is something of a reenactment of the revolution (scraggly rebels each proclaiming, “I am Fidel,” to anonymous army soldiers), we start to consider a meta-text. Just think about those troops, many hundreds of real soldiers pulled off their various bases to film an action sequence in the fourth chapter, shortly after the missile crisis of 1962, and what that must have meant to them, to the filmmakers and to the country. There is too, funnily enough, an explicit storyline about the dangers of propaganda within this propaganda film. A news item falsely claiming that Fidel Castro had been killed in the hills outside of the capital only compels the young activists to take greater and more violent action.

Although there are characters that we follow throughout the film, ultimately it is the unseen, unnervingly felt, inferred perspective that is the real protagonist of Soy Cuba. Perhaps this ghostly “us” is the voice that narrates the film from the vantage of a diffuse Cuban identity (as the title states, “I am Cuba”). A character in negative, a lacuna inviting our attention to the absence of another that we typically expect to find (the one I may be projecting, as this masterpiece wasn’t explicitly intended for Western eyes), the place occupied in other films by the foreign correspondent gone astray, the journalist or expatriate gone to seed, gone to ground but compelled by circumstances to put it all on the line for something like redemption. Somehow this type, in a cinematic history obsessed with the individual, the main character, the star holding the movie together, has been deleted.

From left: Fidel Castro speaking at a rally in Havana, 1961; British newspaper headlines during the Cuban missile crisis, 1962

Of course, the very point of Soy Cuba is to direct your attention toward the idea of Cuba, which is fraught territory for any Westerner—like contemplating the dark side of the moon, a place beyond the event horizon of Western media. For the latter half of the 20th century, Cuba was largely a land of myth, a narrative symbol we knew only as the tool of politicians and ideologues pursuing an agenda. Cuba in general, and Havana specifically, has been known to be trapped in amber, aesthetically, since the time this film was made—its clothing styles and cars and architecture having been updated little. All of which gives the film an ironic prescience, as it seems to still refer to present day Havana, still seems to bring with it an urgency, an immediacy and idealism it ought to have lost. It is a nostalgic period piece that feels au courant. And yet that’s another missing element in the film. Like the visiting hero, it also lacks a happy Hollywood ending.

Still from Soy Cuba