Perceptions of Paradise

By Benjamin Moser

![]()

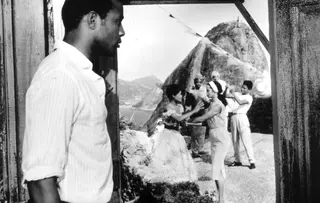

Black Orpheus, dir. Marcel Camus, 1959

PERCEPTIONS OF PARADISE

By transposing the Greek classic to 1950s favelas, Black Orpheus created a complex mythology of midcentury Brazil

By Benjamin Moser

July 5, 2023

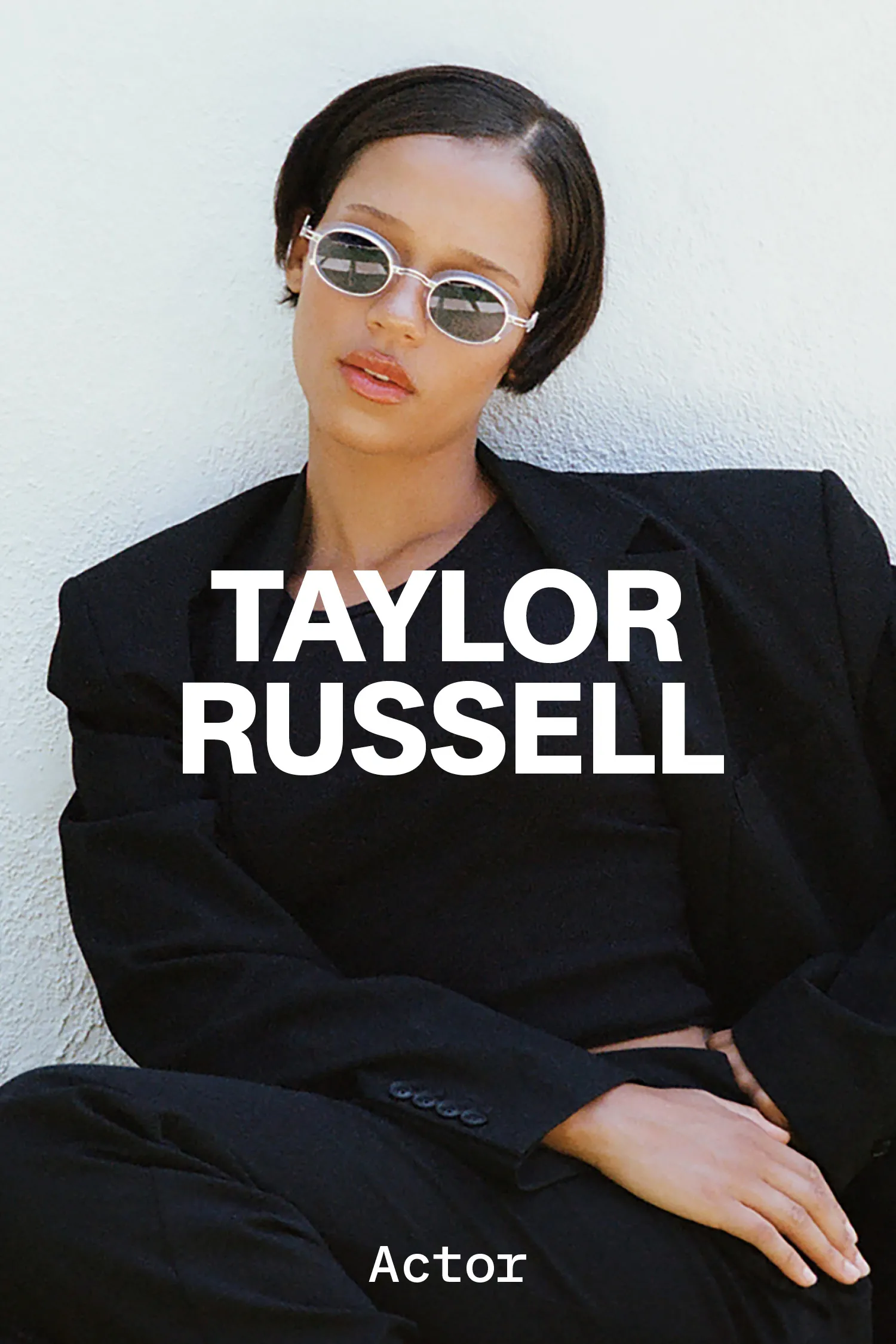

In 1956, Vinicius de Moraes, one of the most colorful figures in Brazilian culture—a diplomat as well as a composer and poet, and a man of such energy that he was married nine times—premiered a play called Orfeu da Conceição, placing the mythic story of the musician Orpheus and the nymph Eurydice into a contemporary setting.

That setting was a Rio favela. The season was Carnival. The cast members, Vinicius wrote, were to be black, as much as possible—a novel proposition in Brazil or anywhere else. The production boasted a spectacular list of collaborators, including Oscar Niemeyer, who would soon be world-famous as the architect of Brasília, and Antônio Carlos Jobim, who would soon be world-famous as one of the creators of bossa nova.

If these elements made the play feel modern and even futuristic, the doomed love story of Orpheus and Eurydice had been ancient even in ancient times. The lyre of Orpheus was so powerful that its melodic accents caused the ghosts of those who lived without light to hasten toward him. It tamed the most savage beasts, made rocks and trees dance, and even charmed the guardians of the underworld. But his spell was broken when he tried to bring Eurydice back into the world of light. The story has been reinterpreted for centuries.

Soon after the premiere of Vinicius’s play, his own reinterpretation was in turn reinterpreted by the French director Marcel Camus. Rechristened Black Orpheus, the 1959 film showed Orpheus—Orfeu in Portuguese—as a beautiful singer and dancer when he isn’t driving a trolley, and Eurydice as a girl from the countryside. She has fled to Rio de Janeiro in order to escape the attentions of a strange man: a man who, we learn, is no one less than Death himself. We know—have known for millennia—how their story ends, and that knowledge makes us watch this courtship with a pang.

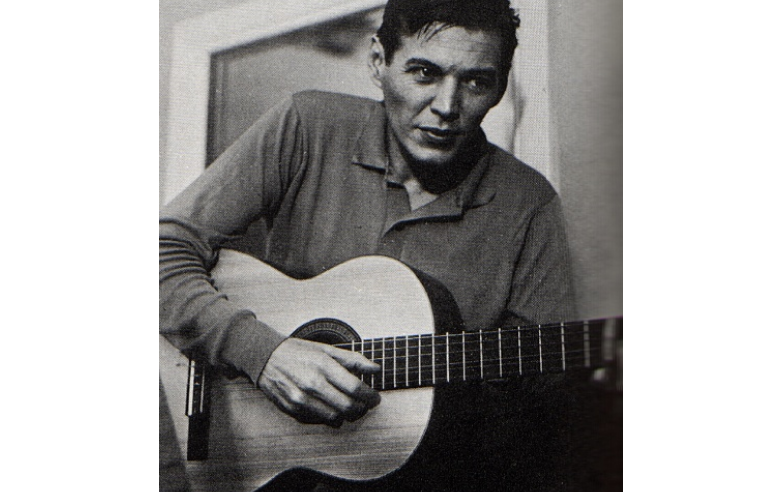

Vinicius de Moraes

To say that there may have never been a more charming film is to risk being misunderstood. Charming, after all, can sound condescending. You can use it to describe something superficial, something light and frothy, something you don’t quite take seriously. But Black Orpheus is charming like Orpheus himself: bewitching, ensorcelling, magical. It casts a spell. It has all the power of myth. You never forget it.

Sixty-plus years after its premiere, it has shaped the way generations of foreigners see—and fantasize about—Brazil. It was a favorite of the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and of the Korean director Bong Joon Ho, both of whom watched it as children. The French actor Vincent Cassel, who now lives part-time in Rio, was first introduced to Brazil by the film when his father took him to see it at age seven. It was also former president Barack Obama’s mother’s favorite—though when Obama saw it as a young man, it made him squirm, with its “childlike black” characters and their promise, to a white girl from Kansas, of “another life: warm, sensual, exotic, different.”

The film enjoyed an unprecedented international success, winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes and the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Like Obama, though for different reasons, certain Brazilians found it tacky, full of sappy sentimental clichés. There was something a bit too picturesque about its perky portrayal of a favela as full of brooding, sexy musicians and the gorgeous girls they loved; something a bit too airbrushed about its sentimentalizing of Brazilian poverty. That it wasn’t an entirely accurate portrayal of the country—well, that gorgeous scene at the end, when two boys use the dead Orfeu’s guitar to make the sun rise over the granite mountains surrounding the Bay of Guanabara, hinted that this depiction might not be the “real” reflection of some “real” Brazil. It was a myth.

![]()

Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasília

![]()

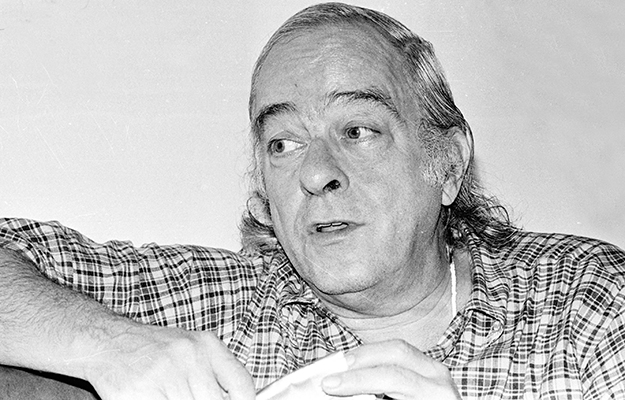

The myth of Orpheus reflects a real human longing: the hope that there might be, just once and just for us, an exception to the rule that all must die. And, likewise, Black Orpheus reflects a real moment in Brazilian culture, for its story is inseparable from the story of bossa nova, in which Vinicius de Moraes also played a central role. The music is traditionally thought to have been launched the year before, with the release of the 1958 album Canção do amor demais. Vinicius wrote the lyrics, Jobim wrote the music, João Gilberto played on two of the tracks, and Elizete Cardoso provided the voice. Rarely, in any country, have so many great names come together on a single album.

Antônio Carlos Jobim

Antônio Carlos Jobim

The bossa nova they pioneered was a radically stripped-down samba, and it was so soft—swinging, sophisticated—that it marked a before and after in Brazilian music, and in how Brazilian culture was perceived. Before bossa nova, Brazil had never been considered sexy. It had never been considered cool. After, it always would be. And the music’s great international success came, in large part, from the success of this film.

Both were part of a tropical Camelot—a moment when Brazil, whose great size promised a great destiny, seemed on the verge of becoming what its citizens had always hoped it could be. After nearly three decades of on-and-off dictatorship, it had a popular, visionary and democratically elected leader, Juscelino Kubitschek. It had a hero: Pelé, who led Brazil to victory in two back-to-back World Cups, in 1958 and 1962. Starting around the time of Vinícius de Moraes’s play, the nation built ultramodern Brasília, a new capital, in the middle of nowhere.

Black Orpheus brought this glamorous new Brazil to the world. Never in history had the nation had such a romantic postcard; never, surely, had any representation of Brazil been so widely seen. When Marcel Camus adapted the play to the screen, he filled it in with all the layers that only cinema can offer. He fitted it with the splendid backdrop of Rio and layered it with all the colors of Carnival, when that most splendid of cities is at its most extravagant. And he gave it a soundtrack, too, surrounding this antique story with the chords of the bossa nova.

Yet ever since its premiere, the film has been controversial: Was it French or was it Brazilian?

You’re not entirely wrong if you’re thinking, Who cares? It was, in fact, an international co-production, Franco-Italo-Brazilian; and though its cast was mostly Brazilian, the actress who played Eurydice, Marpessa Dawn, was from Pittsburgh. But for the viewer who encounters this story for the first time: Who cares?

But you’re also not entirely right, either. The question gets to the heart of the film’s authenticity. Just as many Brazilians cringed at the clichés, conservative viewers were discomfited by its emphasis on Afro-Brazilian characters and themes; left-wing viewers, by portrayals of those same themes in a way that might verge on stereotype. I’m sure we’d do it differently today—we’d do most things differently today—but it’s easy, in an age where the criteria for representation have changed so much, to remember how unheard-of it was to set a Brazilian film in a favela, or to people it with black characters.

Yet to focus too much on race and politics—the favorite themes of so many contemporary critics—is a bit like complaining that Igor Stravinsky, say, or Andrea Mantegna, or Ovid (all of whom adapted the Orpheus myth) did not present an accurate picture of the ancient Thrace in which the “real” Orpheus and Eurydice supposedly lived. That critique obscures the reasons for this movie’s charm. The film is just so beautiful. The actors are beautiful; the landscapes are beautiful; the music is beautiful. And the intensity of their beauty makes us feel all the more piercingly the knowledge that this couple is doomed—that even they, with all their charm, cannot triumph over death.