Rain Man's Radical Honesty

By Andrew Lipstein

Rain Man, dir. Barry Levinson, 1988

Radical Honesty

Rain Man’s inspired performances and candid approach to neurodiversity challenge morality-tale convention

By Andrew Lipstein

February 2, 2024

In the decades since I first watched Barry Levinson’s Rain Man (1988) as a kid, I’m struck by how poorly I remembered it. Not only was I confident that most of the plot takes place inside a casino (in reality, hardly 20 minutes), I recalled a warm tale of brotherly love in which two men grow from strangers to friends, crossing the chasms of personality and ability that separated them. My misremembrance might be attributed to the fact that, in the intervening two decades, I’ve become accustomed to contemporary feel-good narratives. After all, what could we expect from such a setup today—an autistic savant (Dustin Hoffman) meeting a brother he never knew existed (Tom Cruise) after their father’s death—but a heartwarming redemption story? In fact, time had distorted the film in quite a number of ways, though none were stronger—or harder to grasp—than my understanding of Cruise’s role. Through his deceptively complex performance, Cruise manages not only to give his character profound specificity, but simultaneously to embody society at large and the ways in which we so often confront neurodiversity—and fail.

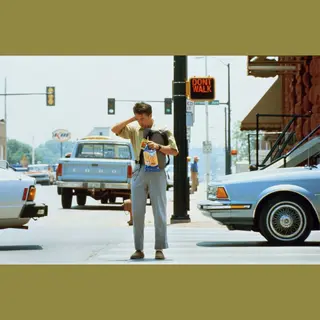

Stills from Rain Man

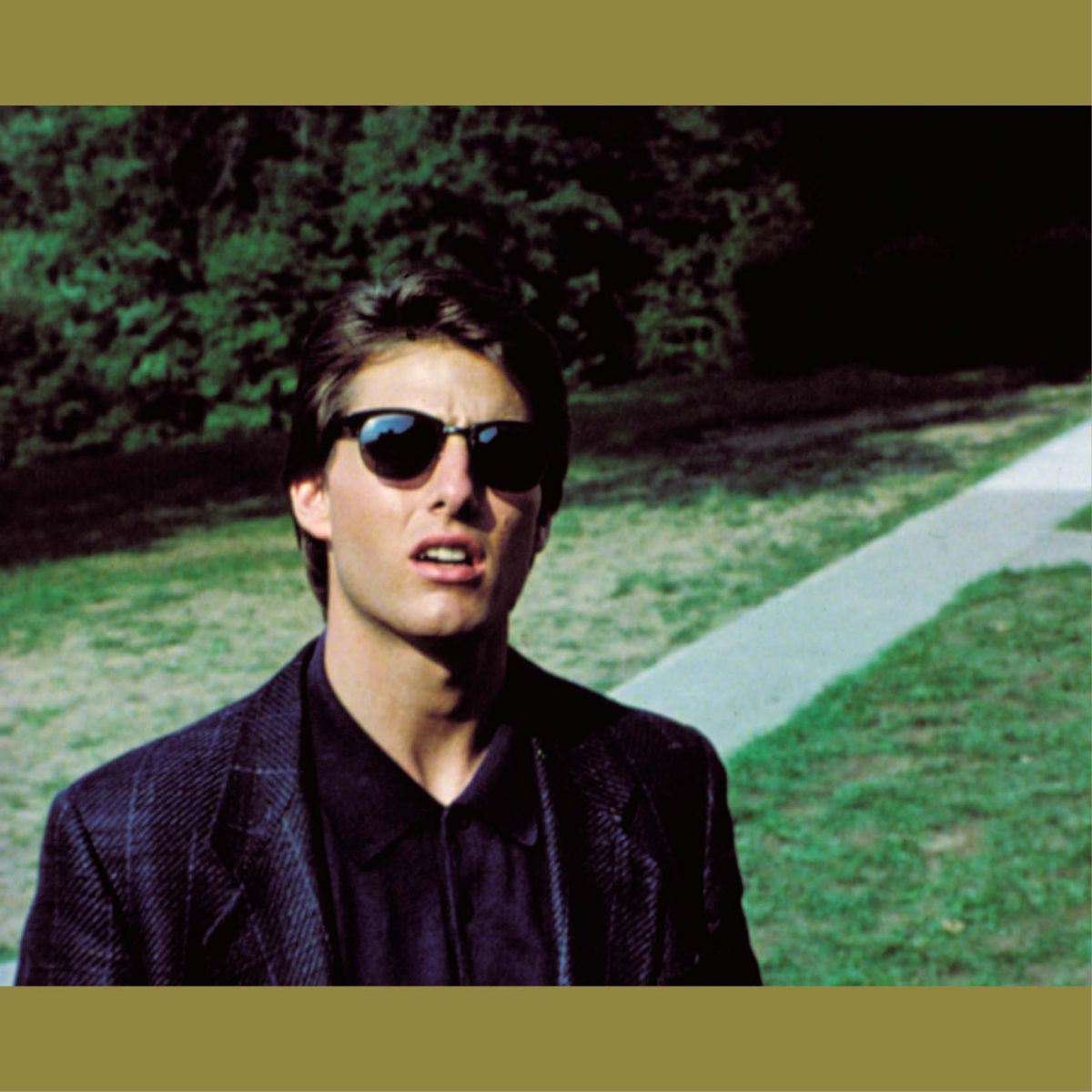

Of course, Rain Man couldn’t exist without Hoffman. The role rightfully landed him his second Academy Award for Best Actor, one of four Oscars the film took home. (Cruise wasn’t nominated.) As Hoffman comes into frame, nearly 20 minutes into the film, we feel nervous—will he rise to such an ambitious role? But then, as only transcendent acting can do, we forget he’s even acting. So empathetic is Hoffman’s performance as Raymond Babbitt, a middle-aged person with autism living in an institution, that we no longer recognize the famous thespian on the screen. It’s too hard to believe that this persona is the same actor who played youth incarnate in The Graduate (1967), a con man in Midnight Cowboy (1969), Carl Bernstein in All the President’s Men (1976) and an ad exec in Kramer vs. Kramer (1979; Hoffman’s other Best Actor Oscar win). The effect only becomes more pronounced as the camera cuts back to Cruise—an actor who has arguably made a career out of typecastability.

By the time Rain Man was released, Cruise was already a certified megastar. He’d been in 11 films, including The Outsiders (1983), Risky Business (1983), Top Gun (1986), The Color of Money (1986) and Cocktail (1988). Which is to say that his appearance in a movie commanded certain audience expectations. We first catch sight of Cruise during the opening credits, as he receives a shipment of Lamborghinis in Los Angeles. His suit, side-swept hair and sunglasses all confirm that we already know this character: the money-driven, rule-bending entrepreneur; the well-dressed, virile charmer; the aggressive but vulnerable and supple young god. And Cruise, as handsome (literal) wheeler-dealer Charlie Babbitt, is all of these. He takes charge, he rolls up his sleeves, he stands with his hands on his hips. He makes quick decisions, he drives in a fast car with a beautiful woman, he even bemoans government intervention. In other words, he’s a man’s man in Reaganland. His manifestation of the era is so crystalline that even today he seems as if he represents all of the ’80s. But slowly, scene by scene, there thrums another aspect of his character, which, once noticed, becomes defining and pervasive: his anger.

Valeria Golino and Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man

Anger can be many things, and Charlie is angry in quite a few ways. First, there’s the bind he’s in because of the Environmental Protection Agency: He can’t deliver the Lamborghinis he’s imported, because they’ve failed emissions tests. He’s angry at the regulators, and his employees, and his clientele. But this anger is effective. It’s a tool. We see in real time as it helps him bend reality to his will: He forces his staff to lie to customers about the state of the cars and, for the time being, staves off disaster.

Then, following news that his father has died, Charlie returns to his hometown of Cincinnati with his pretty girlfriend, Susanna, and we witness another kind of anger. After finding Susanna holding a picture of him and his dad, Charlie yells, “Nothing I did was good enough for this guy. Don’t you understand that?” This ire—latent, uncontrolled, disturbing—is not a tool. We sense it is permanent, the bane of Charlie’s life, and deeply, infinitely painful.

Adjacent to the enmity he has for his old man is the anger Charlie feels upon hearing the contents of his will. He gets his dad’s car (a Buick convertible) and his “prize-winning hybrid rose bushes.” But the home and all other assets, valued at $3 million dollars, is placed in a trust for an unnamed beneficiary. Charlie charms his way into finding out where the trust is controlled, leading him to Wallbrook, a local mental institution. It is there that the unstoppable force of Charlie’s anger meets its immovable object. Over the course of the film this immovable object will prove to be Raymond, the older brother he never knew he had, but even before we get to that point, even before we meet Raymond, the authority Charlie wields over the story—and thus our point of view—has already been dismantled.

Driving with Susanna in the inherited Buick down the tranquil, tree-lined entrance to the institution, Charlie barks to someone on the side of the road, “Is this Wallbrook? Excuse me, is this Wallbrook? Excuse me.” The camera switches to a man with Down syndrome, who is unable to help. We cut to Charlie and Susanna roaming the halls of the facility, where they come to a TV room with several patients. The camera steadies on a young, neurodiverse man, who stares directly at us. For nearly two seconds we lock eyes with him. The moment is destabilizing—uncomfortable, even—not just because we are confronted with this stranger’s humanity but because Charlie and Susanna have already left the scene. They are no longer our guides. Without them, we don’t have a perspective to latch onto; what to think of this man is entirely up to us. Finally, he turns away, as if our own intrusion is too much for him.

Dustin Hoffman and Tom Cruise in Rain Man

“In the decades since Rain Man was released, we’ve begun to appreciate all of the shapes autism can take—reconceptualizing it not as a single illness but as a spectrum.”

Charlie and Susanna approach another room, where patients are making and listening to music. Eagerly, we scour our two characters’ expressions, waiting for some hint of compassion. As Susanna points—the very thing we learn as kids not to do—Charlie is indifferent, if not vaguely disgusted. Impossibly, this moment makes us feel even more alone than the last: The sure-footed protagonists are by our side again, but they do not help us know what to feel.

Soon, while Charlie talks with the director of the institution, we find Raymond in the driver’s seat of the parked Buick with Susanna, who is trying to talk him into getting out of the car. She is direct but accommodating and warm, and we are relieved by her goodwill. But then Charlie comes down the steps, distaste smeared on his face. As he kicks Raymond out, he makes sure, subtly, not to touch the man who, he’ll learn a minute later, is his brother. This moment, suspended in dramatic irony, is both heartbreaking and captivating: We anticipate Charlie’s epiphany, his transformation, his about-face. And then, when it doesn’t come—he continues to be curt with Raymond, mean even—it doesn’t just upset our expectations for Charlie’s character, but for the film itself. It has now become clear that this isn’t a tale of empathy, but its negative image: the limits of connection.

As the story progresses—Charlie takes Raymond from the facility in a misguided bid for his inheritance and becomes his protector—we begin to demand more of Charlie both as a character and as the film’s moral center. His impatience no longer seems like a personality trait, or a response to adversity, but a failure to fill the role he has set for himself. Against the great needs of Raymond—he not only requires a caretaker but someone who understands him, who will make the world safe and predictable—Charlie’s anger reveals itself as a rudimentary reaction, and Charlie himself as insufficient, immature, cowardly. It may not be what we hope from him, but it is achingly accurate in its realism. This isn’t just how someone like Charlie would react to Raymond, it is a mirror held up unflinchingly to a society unable to face mental disability. Of course, in 1988, autism was hardly understood, frequently lumped in with so many other developmental disorders. In one indelible scene, Charlie takes Raymond to a general practitioner. “Well, I’m not a psychiatrist,” the doctor says, “but I do know that his brain doesn’t work like other people.” Then, later in the visit, he states that “most autistics, they can’t speak or they can’t communicate.” But Charlie’s inability to come to terms with Raymond resonates just as much today.

Tom Cruise as Charlie Babbitt in Rain Man

In the decades since Rain Man was released, we’ve begun to appreciate all of the shapes autism can take—reconceptualizing it not as a single illness but as a spectrum. Just as importantly, we’ve prioritized inclusion in media, entertainment and the arts. We now produce films and television shows with (usually charming) neurodiverse characters; pair them with an empathetic, accommodating cast; and watch as they overcome adversity. (A few recent examples include the television show Atypical, which ran from 2017 to 2021, and the films A Brilliant Young Mind, from 2014, and Please Stand By, from 2017.) In this way, we are more equipped and intentional in creating aspirational art, where the moral guidelines are clear and we’re never, for a moment, confused or left to question the proper response to inequity, disparity or disability. But by sweeping the disorder into such swift plot arcs and hopeful morals, we make it facile, comfortable—part of our world, not theirs. At the end of the film, Charlie brings Raymond back with him to Los Angeles, where he finally has his road to Damascus moment and attempts to win custody over his brother. But after a brutal back-and-forth with the director of Wallbrook—who has traveled cross-country for the meeting—and a court-appointed psychiatrist, Charlie concedes that he’s incapable of being Raymond’s caretaker. Left alone, the two men sit with their heads pressed together. “I like having you for my big brother,” Charlie says, to which Raymond replies, “Yeah.” If this is briefly heartening, we soon remember that the psychiatrist has just proved that Raymond’s response doesn’t mean anything, really; he uses it reflexively. This moment between them—warm but opaque, plangent but deficient, conclusive but incomplete—is all they, and we, ever get.