Ship of Fools

By Sean Wilsey

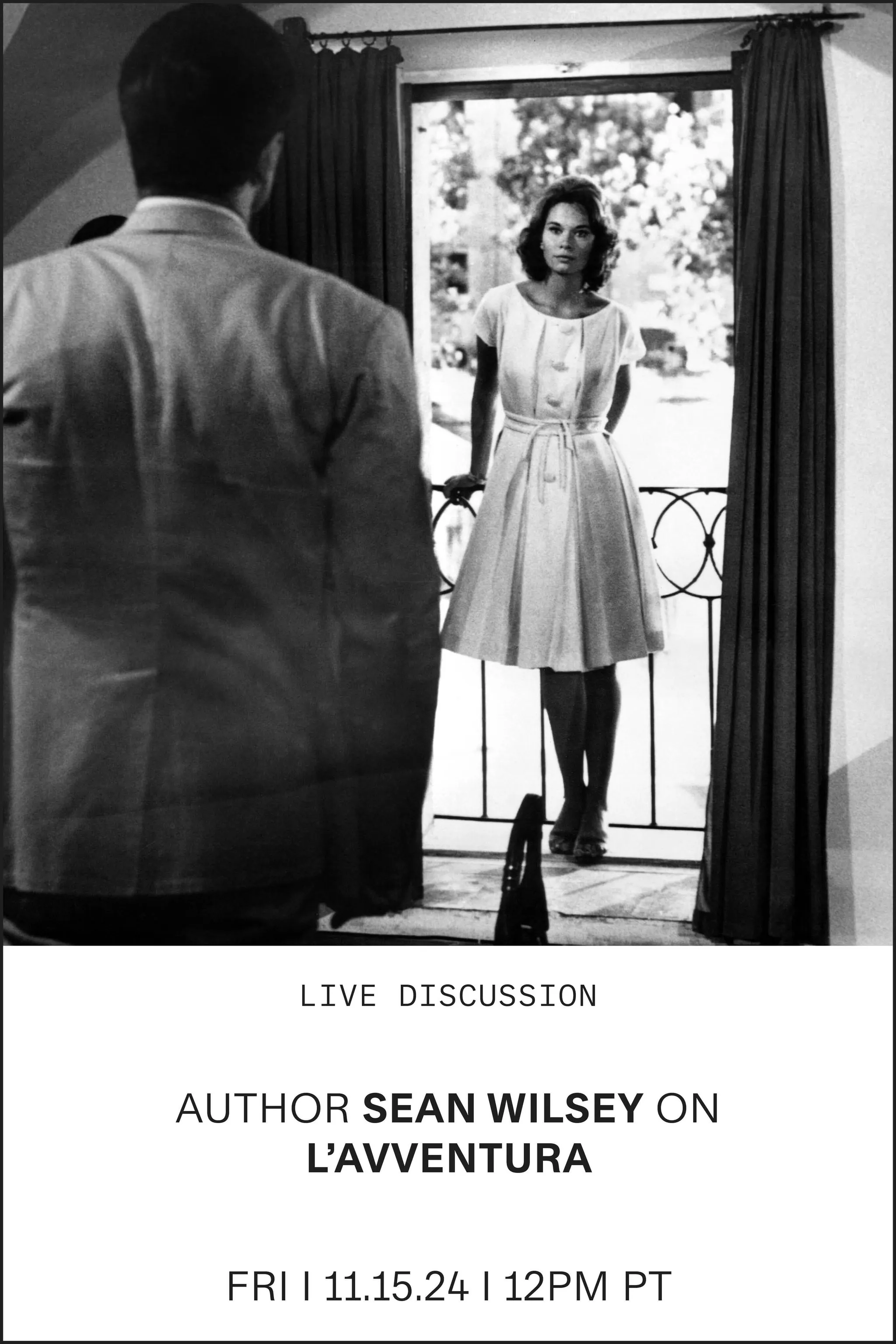

L'Avventura, dir. Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960

Ship of Fools

The film that broke the romantic fairy tale

By Sean Wilsey

November 8, 2024

Michelangelo Antonioni’s sixth feature, L’Avventura, is a piece of cinematic art undiminished by time—as brave, incisive and liberating in 2024 as it was when it premiered in 1960. Beginning in Rome but quickly shifting to Sicily, the film works as a police procedural, a love story (with matter-of-fact swerves into soft pornography), a maritime saga, a road movie and the ultimate shaggy-dog story. All this from a director who’d been a part of the Italian film establishment going back to 1942, when he co-wrote the screenplay for Roberto Rossellini’s neorealist war film A Pilot Returns—aka, the fascist Top Gun. Perhaps in penance for this propagandist debut, Antonioni grew obsessed with cinematic truth, and L’Avventura offers no refuge for delusion. It abandons the conventional tools of filmmaking in a determined effort to avoid manipulating the audience, obliging viewers to experience reality through discomfiting moments of silence and inaction, eschewal of shot-reverse-shot dialogue and a truly minimalist soundtrack, where wind, engines and footfalls largely replace a traditional score, even if everybody’s lines are dubbed. Antonioni had been edging toward this sort of commitment in his prior work, but with L’Avventura he went all in—creating an anti-escapist epic that compelled us to think and carried cinema through the next decade. The guy was a rogue New Wave.

AUTHOR READS

![]()

Michelangelo Antonioni on the set of L'Avventura

![]()

Monica Vitti in L'Avventura

Upon its release, the feature disrupted the 1960 European film world much as Bob Dylan upset American folkies a few years later. But watching it now, in 2024, we might be put in mind of the director’s contemporary American disciples, such as Sofia Coppola and Mike White. Coppola’s conviction that emotional substance can be formed from props and locations, and her reluctance to pass judgment on her characters, are qualities passed down from this filmic father rather than the one on her birth certificate. While White’s elevation of melodrama, in tandem with his appropriation of not just a principal location but whole scenes of L’Avventura, shot for shot, in The White Lotus, is to homage what Guns N’ Roses’ “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” is to Dylan covers.

"Knockin' on Heaven's Door" – Bob Dylan

Among the film’s principal questions is one that Antonioni put forward in a statement he prepared for the film’s premiere: “Why do you think eroticism is so prevalent today in our literature, our theatrical shows, and elsewhere? It is a symptom of the emotional sickness of our time. But this preoccupation with the erotic would not become obsessive if Eros were healthy, that is, if it were kept within human proportions. But Eros is sick; man is uneasy, something is bothering him. And whenever something bothers him, man reacts, but he reacts badly, only on erotic impulse, and he is unhappy.” Fittingly, the film’s title can be translated into English as either The Adventure or The Fling—inviting us to choose between the grand or the trivial. Here, doubles and about-faces proliferate. Perhaps my favorite: Despite its origins in a phallocentric era (Rocco and His Brothers, Spartacus and Ben-Hur were the big movies in cinemas at the time), it is a film in which every man is a failure, a cheap joke driven by vanity, lust, boredom and greed—a misandrist masterpiece—while women speak to each other with substance and intention. The Bechdel test is passed immediately in a series of conversations between close friends Anna (Lea Massari) and Claudia (Monica Vitti)—the former rich, the latter “very sensible,” as she puts it, subsequently explaining, “I mean I didn’t grow up with money.” Claudia’s the innocent odd-one-out in a group of seven pleasure-seekers cruising the Aeolian Islands on a markedly too-small yacht, their overnumerousness clueing us in to the fact that they are clowns.

L'Avventura stills from left: Lea Massari and Monica Vitti at sea; Gabriele Ferzetti and Lea Massari on land

This is the same rudderless society flotsam the world met that same year in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, but drained of all joy, instead picking each other’s scabs, laughing at things that aren’t funny, overworking their exhausted staff. Vitti, as the only relatable member of this soul-sick band, is a comic actor cast in a role that forces her to play it sad. She’s Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson in Lost in Translation. Lust is everywhere, though mostly in brooding mode, where it always seems close to grief. It’s as if Coppola and White went back in time to co-direct a black-and-white episode of Gilligan’s Island.

Numerous shots are anchored by landscapes so gorgeous that the suffering humans in the foreground seem absurd (tiny flings in nature’s epic adventure). Characters stand in gravel before a cheap real estate development as St. Peter’s Basilica rises like the moon at the horizon. Anna and Claudia talk in a plaza where a classical arcade rears up behind a billboard. Men and women struggle with momentous emotions in the shadow of volcanoes. Stromboli (a shout-out to Rossellini) and Etna preside over the interpersonal drama. Close shots allow these same characters to spill majestically out of the frame, pulling us in with a sense of collusion and claustrophobia, restoring their significance.

Anna is introduced as the film’s heroine but, after spending half an hour as the center of attention, she disappears. A shark sighting shortly before she goes turns out to have been her invention. “Pescecane!” she screams, causing everyone to swim back to the boat, which then anchors off the Gilligan-sized island of Lisca Bianca (literally, “Smooth White” or “White Bone”), from which she evanesces. Claudia, the ignored understudy, becomes the camera’s new center of attention. A search begins, complete with helicopter, frogmen, hydrofoil…but never mind. At this point in the film, all pretense of interest in what has become of Anna is jettisoned. A boulder comes crashing inexplicably through the frame and into the sea. Nobody reacts.

“The film’s title can be translated into English as either The Adventure or The Fling—inviting us to choose between the grand or the trivial.”

It’s reasonable to assume that Anna is fleeing two men: first her diplomat father (Renzo Ricci), who puffs up like a panettone when referred to as “Eccellenza” (Ricci, a theater actor, gives a deft flick of his chin in reply to Claudia’s “Buongiorno!” when she comes to pick up his daughter for the cruise, and we know instantly how significant she is); and then her architect fiancé, Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti), a man of no substance who has fallen ass-backward into money through his facility for calculating construction estimates—his being a type familiar to anyone who followed the story of the accused Gilgo Beach killer, Rex Heuermann: the expediter.

“It’s strange,” Sandro says. “I never imagined myself getting rich. I pictured myself in a rented room, ‘a man of genius!’ Instead I have two houses—one in Rome and one in Milan.” A visual joke occupies one wall in his Roman pad: 23 fire pokers. Anna looks at him pityingly, strolls past this phalanx, and begins to unbutton her dress. The man of genius is the man behind the camera.

After Anna disappears, Sandro and Claudia strike out across Sicily in search of her, but soon become lovers. At the time, the audience reaction against Antonioni for frustrating all expectations was explosive, especially in the Italian literary world. Maybe writers were threatened by this radical visual-narrative triumph. In his 1963 essay collection, Facce dispari (Odd Faces), the critic Giuseppe Marotta wrote, “They call him a novelist and he only strings together anecdotes; they call him a psychologist while he skims the surface of every character; they call him literate, and when it comes to language he is a house of straw.” In a 1962 article in L’Espresso, novelist Alberto Moravia declared, “Antonioni is like certain solitary birds that have only one song to sing and rehearse it night and day. Through all his films, he has given us this line of his and only this…estrangement, alienation, the aridity of relationships and the impossibility of loving.”

![]()

Scarlett Johansson and Bill Murray in Lost in Translation

![]()

Aubrey Plaza in The White Lotus

In May 1960 the film premiered to derision at Cannes. When Vitti took almost 30 seconds to run down the same Sicilian hotel hallway where various White Lotus cast members would taunt each other 62 years later, people in the audience began to laugh, boo and even holler, “Cut! Cut!” Antonioni and Vitti left the theater humiliated, Vitti in tears. A petition (signed most prominently by Rossellini) circulated to give the film a second screening, which it received. Eventually, it shared the Jury Prize with Kon Ichikawa’s category-repellent incest-and-impotence satire Odd Obsession (1959). The editor of Cahiers du Cinéma, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, wrote, “The grotesque jeering at Cannes was to be the last gasp of the imbeciles: a curse that trailed off into the snickering of their little world of shit. It can’t drown out the sound, long in coming, of glory’s trumpets.”

It bears mentioning that the audience wasn’t solely composed of imbeciles from Planet Shit, and even had some provocation. An anti-Gallic thread runs through L’Avventura. A French novel is overlooked in favor of a jigsaw puzzle. French tourists are run out of a beach town for their embarrassing bathing suits. Dominique Blanchar, a well-known actress, is a repeated punch line and eventually gets seduced by a teenager (“There is no landscape as beautiful as a woman,” he says). Snatches of French in the background of an ensemble scene at the San Domenico Palace are meant to sound ridiculous. But I see that audience at Cannes as mourners who can’t stop laughing at a funeral. A funeral for a cinema that wasn’t coming back.

Tagged an existentialist, Antonioni aligned himself with Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical phase, from 1910 to about 1919, when the Italian artist’s work employed bizarre perspectives to present empty squares, locomotives and broken statues in the background, dressmaker’s dummies filling the foreground (the empty cavities of their bodies stuffed with architectural ornament), all of it vibrating with implication. Shots in L’Avventura replicate de Chirico perspectives, and even specific canvases, among them 1913’s The Anxious Journey, on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Antonioni was to de Chirico what Mike White is to Antonioni, a gifted acolyte taking great pains not just to film the maestro’s paintings but to cast his mannequins—for what else are the men of L’Avventura?

Monica Vitti and James Addams in L'Avventura; The Anxious Journey by Giorgio de Chirico, 1913; Monica Vitti in L'Avventura

In the end, Sandro betrays Claudia and she absolves him, the two characters arriving at what Antonioni called “a sort of reciprocal pity.” Is it an accident that—like Satan and Christ—their names begin with S and C? Antonioni said of the film, “When I finished L’Avventura, I was forced to reflect on what it meant.” As for the “impossibility of loving” decried by Moravia in L’Espresso, I see the opposite. If you read the screenplay, you might come to such an arid conclusion. But the beauty of what appears onscreen seems overpoweringly optimistic to me. A woman can walk out of her unhappy life without a trace. A human being can fall in love at any time and under any circumstances. Forgiveness is waiting around the corner. We are surrounded by the eternal.