Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria

By A.S. Hamrah

Memoria, dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2021

Sound Sleeper

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s latest feature depicts an encounter with the uncanny that unravels a rational mind

By A. S. Hamrah

July 5, 2023

Apichatpong Weerasethakul began to hear a loud boom in his head while he was working in Colombia six years ago. One morning, gathering ideas for the film that would become Memoria (2021), he “was startled by the sound of an explosion. It was a bomb, at dawn, not from elsewhere but within my head. This, I later learned, is called Exploding Head Syndrome,” he explains in the introduction to a book on the film.

Exploding head syndrome is real, even if the sound Weerasethakul heard was not. It’s an auditory hallucination that occurs during sleep, usually near falling asleep or waking. It’s loud and can be frightening to its hearer. Its cause is unknown, and the condition is untreatable. The hearer searches for the source of this booming sound, convinced of its authenticity. But it’s all in his head—he just doesn’t know it yet.

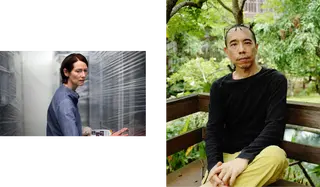

From left: Tilda Swinton in Memoria; Weerasethakul on the set of Memoria

Strange phenomena are Weerasethakul’s métier. Peculiar sensations, portents and apparitions make regular appearances in his work. They are presented as plain and real. The Sasquatch-like forest creatures in Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) are maybe the most famous of these ghostly images, but it’s the ending of that film, with the unexplained and casual doubling of its characters, that is most eerie. Instances of the otherworldly slowly take over Weerasethakul films, which are otherwise set in the recognizable daily reality of contemporary Thailand. One wouldn’t necessarily call them attacks, but odd afflictions send his characters to doctors’ offices in search of explanations and remedies. Things develop in a Weerasethakul film in calm, provocative uncertainty. Everything, visible or not, has a feeling of real presence.

In Tropical Malady (2004), a huge tree shimmers at night with radio voices and static, lit from behind with bright light. We hear it as much as we see it. Whether natural or man-made, these combinations of sound and image, unique to Weerasethakul, seem on the way to becoming something else, to revealing the true nature of their existence in just one more second. They hover between the world of the living and another dimension, one of dead voices and dark silhouettes.

This uncertainty is an effect of the cinema itself, a mechanical art which exists in the same space as these phenomena, a place where sleeping images, often of people no longer alive, are revived every time they are run through a projector. Weerasethakul has this reanimation, giving the dead another chance to appear and to speak, as his focal point. He brings a kind of liminal existence back to life at a time when spiritless digital images dominate movies around the world. He’s made nine features so far, of which Memoria is the most recent.

It’s his first film made outside of Thailand, but expatriation has not hurt his work. Weerasethakul has brought his cinema with him. The story may be specific to Colombia’s violent political history, its geography and its weather, but as a character in Memoria puts it, “In this town there are many people with hallucinations.”

From left: Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2010; Tropical Malady, dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2004

In 2018 the actor Connor Jessup made a documentary called A.W. A Portrait of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. In it, Weerasethakul and Jessup, in a skiff on a river in Colombia, discuss the film that would become Memoria. Weerasethakul mentions how in dreams, you don’t see your own face. This observation is key to the filmmaker’s style, especially in Memoria, where the presence of an international star in the lead could have altered how he does things, as it has done with otherwise intractable directors, from Béla Tarr to Wong Kar-wai, when they have made movies with big names outside their home countries. But Tilda Swinton does not even get one close-up in this film. Instead, Weerasethakul makes novel use of her well-known capacity to seem in touch with aliens, to be other.

In Memoria, Swinton, as a Scottish botanist in Bogotá, is the one awakened by the booming sound Weerasethakul first heard in his own head. In the Memoria book, the director explains their twinned position. Like him, “For a second, she wonders if she is still in that film, lying in bed, opening her eyes from a dream.”

Weerasethakul told Giovanni Marchini Camia, the co-author of the Memoria book, that the first conversations he and Swinton had were about what it meant to be an alien, “both in the most extreme sci-fi sense, and also in the most mundane, completely universal sense of feeling alienated by society, or feeling in some way isolated and solitary.”

In a later interview with Camia in the Metrograph Journal, he explained that Swinton is also playing a ghost. “I think she realizes that she doesn’t exist. She’s an entity, she’s a ghost, and she’s cinema, you know?…She’s the one who carries images and sounds.”

“SHE’S AN ENTITY,

SHE’S A GHOST,

AND SHE’S CINEMA,

YOU KNOW?”

Whatever she is, in the first two-thirds of Memoria she and Weerasethakul suggest that she is going crazy. At a neurological level, Swinton conveys a sense of being off, of being half there. When she and her sister discuss the “Uncontactable”—tribes of indigenous people who live in willful isolation—she too seems like she is becoming one of the invisible people. Maybe that phrase also relates to her status as a middle-aged woman, but it’s a term that applied to the “disappeared,” citizens who have been forcibly vanished by government forces as a result of ongoing political protest in Colombia.

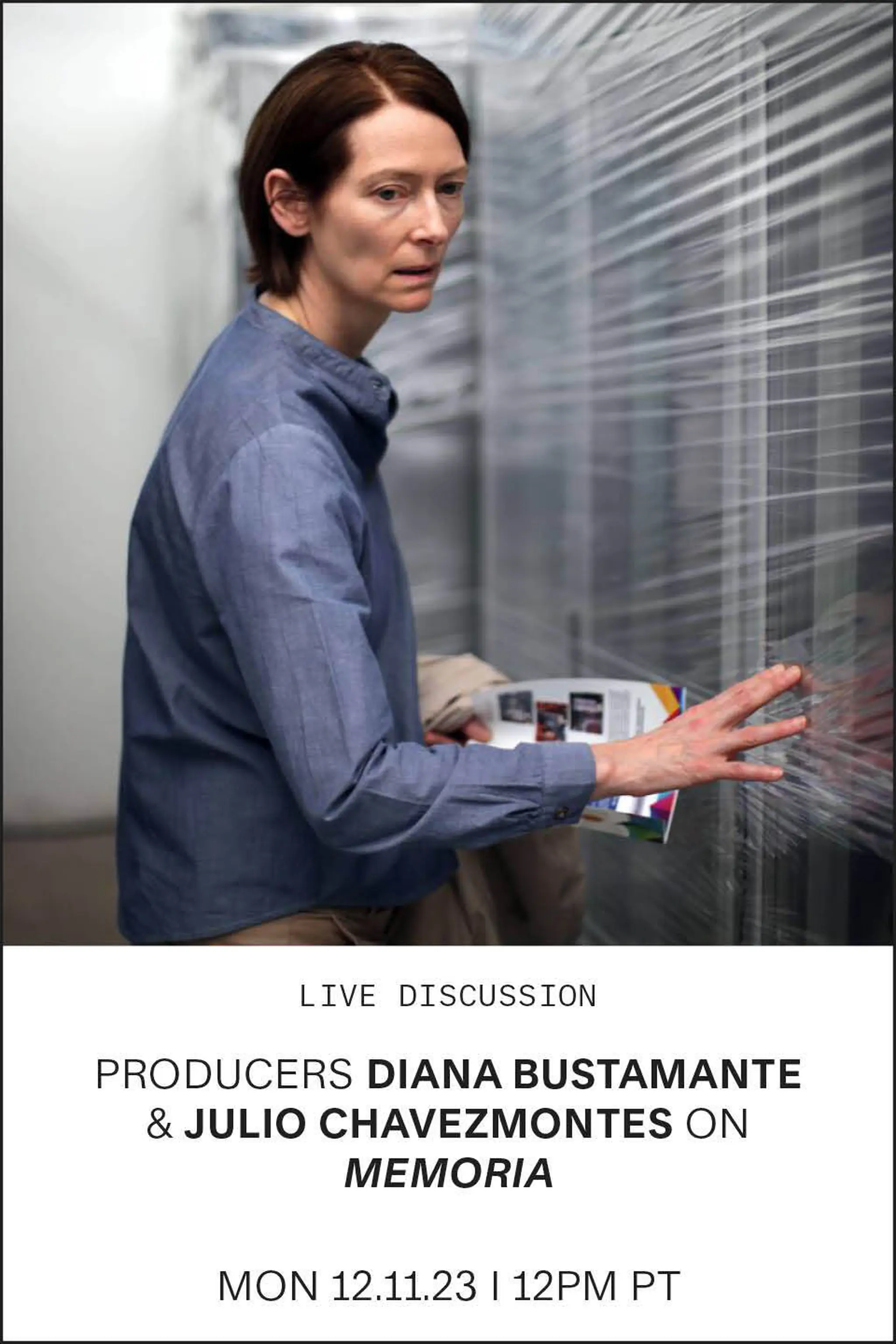

Tilda Swinton in Memoria

Weerasethakul subtly connects this to the situation in his own country, where resistance is quashed by the military, and the monarchy demands absolute obeisance. In the documentary he calls Thailand “a bullshit country” where he has been “lied to too much,” describing it as an authoritarian gerontocracy defined by propaganda. Earlier he says the ghosts in his films are not actual ghosts, but “memories of ghosts.”

Neon’s release strategy for Memoria makes poetic sense in that regard. As the film’s U.S. distributor, the company decided, with Weerasethakul and Swinton, to release the film in cinemas on an eternal tour only “in theaters…forever.” Like a ghost ship, Memoria will sail the seas, stopping at ports, but it will never be digitally stripped for parts on home video and streaming. (Not in the U.S., anyway.)

The sound in Memoria is, in any case, highly dependent on theatrical exhibition. The noise Swinton’s Jessica keeps hearing has a booming fullness that catches audiences off-guard. In a theater, it’s felt inside the body. A sound engineer in the film explains it to Jessica in his studio. “The bass depends on what you use to listen to the sound. On headphones, on a TV set, in a cinema, or with a sound system like this.” He finds a sound-alike file in his system called Stomach hit wearing hoodie and plays it. “It’s between sixty and a hundred hertz,” he points out. (Everybody hertz.)

Jessica studies the fungi on orchids. A worker at a refrigerator factory that makes floral display coolers explains the way they preserve plant life: “In here, time stops.” Anyone who has watched a Weerasethakul film at home has had the experience of pausing it, then coming back to the film and hitting Play, only to be unsure the film is actually moving again. Memoria’s key scene is exactly like that, with an older version of the sound engineer lying in the grass either asleep or dead, in a shot Weerasethakul holds for a minute and a half, then later repeats for thirty more seconds, ages of screen time that make the viewer wonder what the difference is between stillness and sleep, death or a dead battery in the remote.

Sound and stasis create empathy in Weerasethakul’s films. As Jessica becomes more sleep-deprived, she consults a village doctor and asks for a Xanax prescription. The doctor won’t give it to her. “It will make you lose empathy. You no longer will be moved by the beauty of this world. Or by the sadness of this world.” Then she gives her a religious tract and tells her to look at the Dalí in the local church. Jessica gets her Xanax from another doctor.

From left: A Conversation with the Sun, Apichatpong Weerasethakul/MIT Media Lab, 2022; a scene from Memoria

Things being what they are in the worlds of independent cinema and international arthouse film production, Weerasethakul cannot survive as the writer-director of only feature films. He also makes lots of shorts and creates gallery installations. Lately he has dabbled in virtual reality, making something called A Conversation with the Sun (2022) in VR. He’s come away from the experience seeing VR not just as a possible source of cinema’s death, but also—if people become too dependent on it—as a threat to daily life. “VR cannot replicate this idea of [cinematic] point of view,” he explains to Camia, “or even the idea of empathy.”

We learn in their book that making Memoria cured Weerasethakul of his own exploding head syndrome. “In Bogotá and 300 km away in Pijao, as I was making Memoria, the morning ‘bang’ disappeared. With it the precious, murky, drifting realm was gone. For better or for worse, I could sleep for seven hours a night. This was another answer.” Though at this point I have forgotten what the question was, it must have something to do with how to live in this world.

But that reminds me: In my own way, I can attest to this healing power of Weerasethakul’s work. One of his films improved my health. In Cemetery of Splendor (2015), a character played by Weerasethakul’s favorite actor, Jenjira Pongpas, suggests taking ginkgo to someone having memory problems. I started doing that after I saw that film, and it worked. Since then, my recall has improved. I’m like the sleeping/dying character who tells Jessica, “I remember everything. So I try to limit what I see. That’s why I never watch movies or TV.… There are plenty of stories already.”

The character goes on to say that he has never left his village, has no desire to go anywhere, and has realized that “experiences are harmful,” so I’m not sure he’s the exact right model for how to live in this world. “Our kind never dreams,” he says. “What happens when you sleep?” Jessica asks. “Nothing,” he tells her. If only the cinema could cure insomnia too, instead of just being an alternative to sleep.