Street Level

By Matthew Specktor

Boyz n the Hood, dir. John Singleton, 1991

street level

In Boyz n the Hood, John Singleton’s groundbreaking perspective on inner-city Los Angeles illuminates invisible power structures

By Matthew Specktor

February 2, 2024

Hollywood used to make movies about the American family, movies in which the organizing concept might be as simple as a middle-aged couple’s divorce or the death of a child. These domestic dramas came thick and fast during the 1970s and ’80s—think Kramer vs. Kramer or Ordinary People—but by the early ’90s this genre had largely vanished from the industry’s lexicon. What came next was violence on an increasingly grand scale: the apocalyptic threat of alien invasions and freak weather events, a tendency toward catastrophe that still hangs over our cinema today. In 1991, however, we were given an extraordinary, genre-defying movie that knit together domesticity and brutality, that filtered the epidemic of violence in urban Black neighborhoods fed by Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs through the softer lens of a not-quite-amicably divorced couple’s attempt to steer their teenage son through a wayward adolescence.

Boyz n the Hood

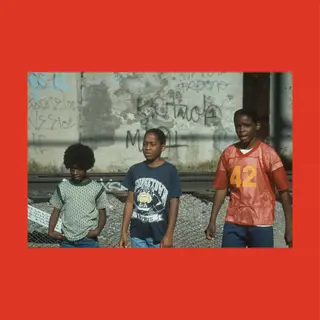

The first thing we see in Boyz n the Hood (1991) is a pair of title cards informing us of homicide rates in the Black community (“One out of every 21 Black American males will be murdered in their lifetime”). The second is the image of a stop sign pocked with bullets. Such overt messaging—Stop the violence, get it?—might skew toward the bathos and sentimentality that tend to haunt Hollywood films trying to tell a “serious” story about race (consider the white-saviorism of 1988’s Mississippi Burning or the phony piety of 2004’s Crash). But first-time director John Singleton’s establishing shot quiets these anxieties immediately. The stop sign isn’t captured straight on but rather is shot from below, seen as if from the perspective of the film’s child protagonists. An airplane drifts vaporously overhead, moving through a cloud-bound sky, the boxy architecture, the low-slung wires and antennae of Los Angeles’s Inglewood flats looming as the camera pulls close on the sign and then cuts to join a group of children on their way to school. They stop to gawk at the bloody pavement left at a murder scene, where preadolescent Tre, a thoughtful, confident kid with a rebellious streak, explains to his friends why the bloodstains have turned yellow. “That’s what happens when it separates from the plasma,” he says. It’s a deft touch, indicating not just that Tre’s a precocious boy, but that he might have seen these stains before. But Tre has discipline problems at school, and it isn’t long before his mother, Reva (Angela Bassett), ships him off to live with his father, Furious (Laurence Fishburne), in South Central, hoping Dad will be able to “teach him how to be a man.” In so many words, that’s the premise of Boyz n the Hood: Furious’s efforts to keep his son (Cuba Gooding Jr.) on the straight and narrow while Tre’s neighborhood friends Ricky (athletic and charismatic, played by Morris Chestnut) and Doughboy (Ricky’s luckless older brother, played by Ice Cube), remain substantially more at risk. The modest plot is standard fare for a domestic drama, but it plays out as anything but.

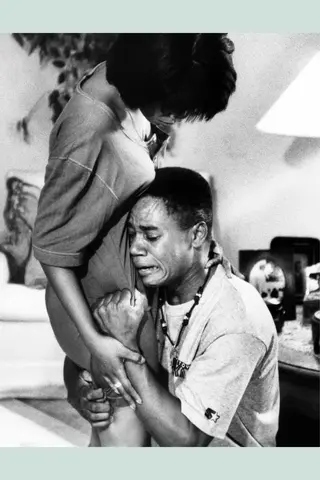

Tyra Ferrell and Cuba Gooding Jr. in Boyz n the Hood

“The camera won’t separate itself from these people (“my people,” as Singleton said), but it will gently remind us of their place in a larger city and the palpable looming authority that hovers above the frame.”

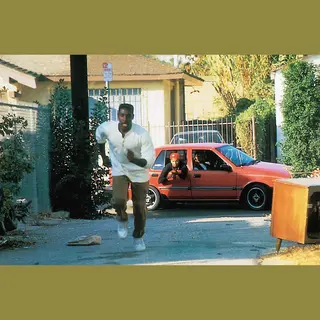

Let’s return to that first shot of the airplane flying overhead. If you’re from Los Angeles, particularly anywhere inland of its coastal cities—east of Interstate 405—you know how infinitely landlocked it can feel. As one drives east, away from the water, through Inglewood or West Adams or Burbank, the streets wind on for miles until the ocean is practically notional, more rumor than reality. It’s telling that a tender early scene between young Tre and the usually strict Furious happens at the beach, where the two have escaped for the day and even Furious can relax a little. That there’s no easy way out of their neighborhood, or their community torn by violence, is a commonplace for Tre and his friends. But Singleton elevates his camera just enough at crucial moments to lend this fact a more visceral and thoughtful valence. When Tre moves from his mother’s place in Inglewood to his father’s in South Central, we get a crane shot, one that frames the sunbaked, autumnal corridor of the street flanked by a scattering of slightly desiccated palms—and young Ricky tossing a football with his friends in the middle of it—from about 20 feet above. After Tre has finished raking the dead leaves off of his father’s lawn (Furious wastes no time in laying down the law), we get a similarly elevated shot, this one saturated with melancholy twilight as Furious’s red convertible VW Bug gleams in the driveway. The human scale of these aerial shots is precisely the point: The camera won’t separate itself from these people (“my people,” as Singleton said), but it will gently remind us of their place in a larger city and the palpable looming authority that hovers above the frame. The characters’ loving interactions may dominate our focus, but we cannot forget even for a moment how those interactions are circumscribed.

This obsession with verticality doesn’t restrict itself to camera angles: steadily—constantly—we hear the drone of helicopters, the LAPD’s inescapable surveillance of the neighborhood (indeed, a child’s drawing of a police helicopter is pinned to a wall of young Tre’s classroom). The film’s sound design is meticulous in its weaving of music, sirens, dogs and neighborhood clatter, but it’s the invasive clamor of airplane noises and helicopter blades that reminds us that Tre’s world is governed by higher forces. The bullet-riddled Reagan 1984 campaign poster (“Four More Years”) we see in the opening scene isn’t just ironic trimming. It’s a reminder that four more years of this administration’s draconian drug policies will amount to four more years of hell.

Boyz n the Hood

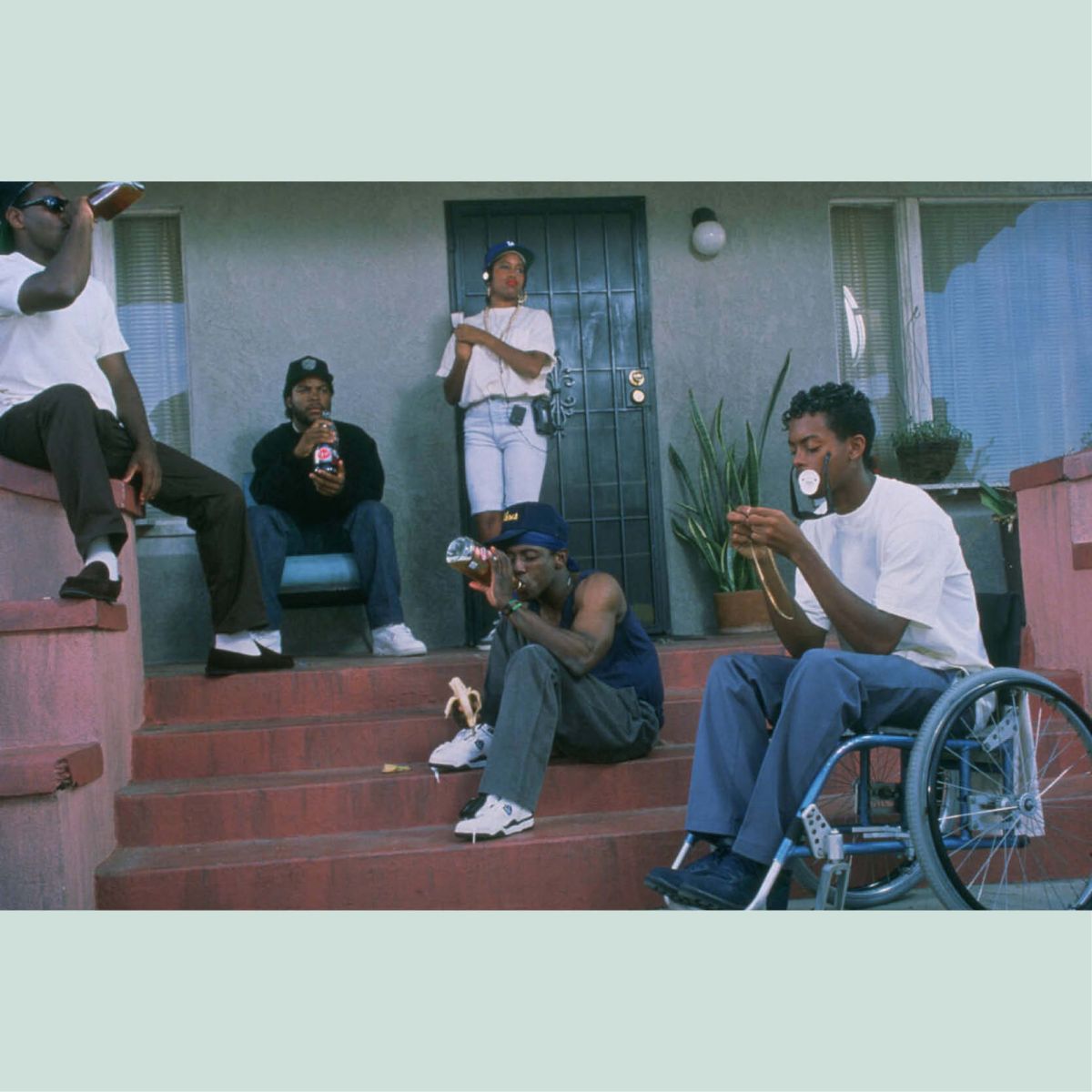

Singleton shot the film with veteran TV cinematographer Charles Mills, using Arri cameras and Arri/Zeiss lenses, on Cimarron Street in South Los Angeles, a quiet block nestled close to the then gang-torn Chesterfield Square neighborhood. Within the fragile peace of this particular location, the film’s far more personal horizontal drama unfolds in contrast. The rich, lateral pageant of the characters and their intimate relationships—not just within the family but also as friends, neighbors, crushes, lovers and ex-lovers—and the way the film braids those lives across time, hangs in counterpoint to the aerial oppression, offering an alternative that can only triumph in flashes, in the joy of a rambunctious house party or a mellow afternoon barbecue. The movie’s focus may be on the family, but this family exists within a much wider net, and it’s the tension between its vertical gestures (the camera angled up, for example, when Tre emerges from his father’s house and stretches on the stoop, as if we’re basking at the foot of a statue) and the community’s horizontal ties with its single-story homes on flat, open avenues that builds its dramatic conflict.

It’s no accident that the movie’s climactic moment unites the earthbound dream of escape with its theme of surveillance: Near the end of the film, just before Ricky (awaiting word on test scores that might earn him a football scholarship to USC) leaves the house on the fateful errand that will see him killed, he is seduced by a television commercial for U.S. Army recruitment. It’s core image and sound? A helicopter lowering itself down into a grassy field. The only way out is to join the Army. Or the police, which only means becoming an instrument of violence oneself. Indeed, it’s telling that we see the cops on the ground just twice in this movie: once when they respond dismissively late to Furious’s report of a robbery and again when the same Black officer pulls Tre over and threatens him sadistically with his gun. In the latter case, we view the officer from Tre’s perspective, looking up at him as Tre is bent back over his car hood as if to underscore the point: What threatens these young men is not the streets but a threat that imposes itself from the top down.

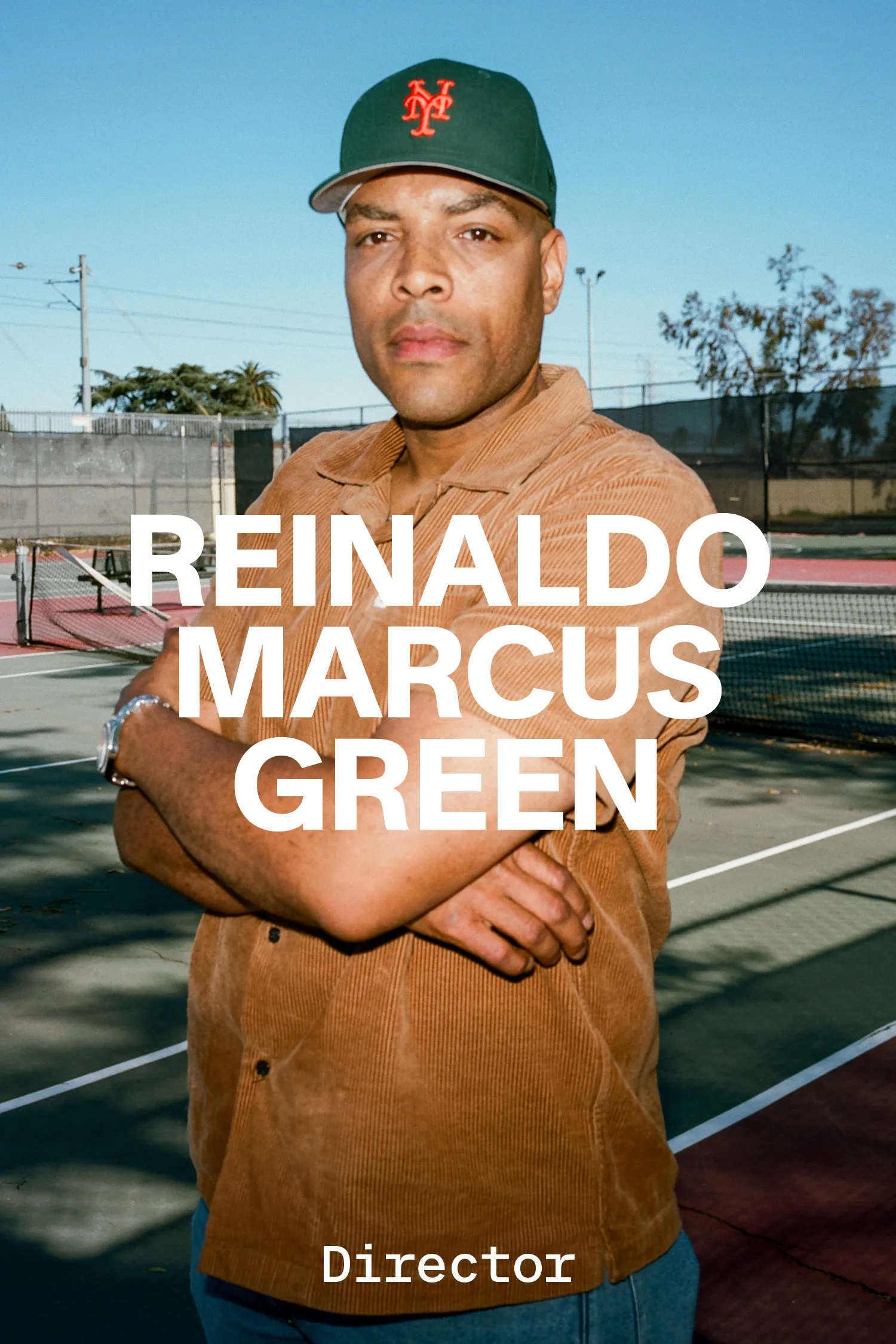

John Singleton

Upon its release, Boyz n the Hood was a decisive commercial and critical success, earning almost ten times its $6.5 million budget and making the deal Columbia had offered Singleton up front seem prescient. Singleton became the first Black filmmaker, and the youngest filmmaker overall, to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Director. He would go on from there to a distinguished career that included commercial hits like Shaft (2000) and 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003), but none of his subsequent projects would carry the same intimacy and emotional intensity as his debut. The film may have been shot in a city that promises all kinds of escape, from Hollywood glamor to its unconfined sprawl, but Singleton’s artful genius came in documenting the subtle, conflicting pressures on his own home turf. The film ends with some text that informs us, American Graffiti–style, of its remaining characters’ fates: Tre will depart for Morehouse College in Atlanta and Doughboy will be murdered in two weeks. But its last visual image is of Doughboy trudging slowly across the street, having just articulated to Tre how senseless all this violence feels to him, and how the media will cover endless foreign wars but say nothing about the brutality here at home. This time, the camera only barely elevates, raised up on Tre’s front stoop as Doughboy departs, his walk as weary and fateful as John Wayne’s slow departure in the iconic final shot of The Searchers (1956). As yet another police siren pierces the distance and yet another chopper circles overhead, the camera stays on Doughboy and lets his image simply dissolve, until we are left with empty vista, another young man’s body vanishing into the L.A. ether.