That Nude Scene

By Mia Levitin

The Last Picture Show, dir. Peter Bogdanovich, 1971

That Nude Scene

A pivotal reveal in The Last Picture Show marks the junction between ’50s repression and ’70s revolution

By Mia Levitin

May 1, 2024

There are nude scenes and then there are nude scenes. In the litany of “bits” parading across cinematic history, very few stand out as pivotal to their films’ plots. Cybill Shepherd’s poolside strip down in The Last Picture Show, however, is one of that handful. The act of transgression by Jacy Farrow, the coquettish high school senior played by Shepherd in her film debut, embodies the vulnerability and triumph of physical agency inside a culture of repression.

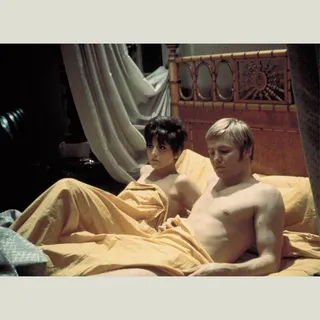

From left: Cybill Shepherd and Jeff Bridges in The Last Picture Show; Shepherd as Jacy Farrow

Peter Bogdanovich’s 1971 adaptation of Larry McMurtry’s semi-autobiographical novel unpacks the social tensions in small-town Texas in the early 1950s. The film explores how sex is used as a means to various ends—whether in pursuit of social status, to stave off loneliness or to exact revenge. Filmed in McMurtry’s hometown of Archer City, it follows two high school seniors, Duane Jackson (Jeff Bridges) and Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms), from one football season to another in a declining oil town. Thanks to its sharp script and phenomenal performances, The Last Picture Show was a critical and box-office success, earning eight Academy Award nominations.

At a school dance, Jacy, who has been dating Duane, accepts an invite to a skinny-dipping pool party in a nearby town. There’s only one catch: As a naked female guest tells her when she arrives, “you gotta get undressed out there on the diving board.” Eager to fit in, Jacy awkwardly yet defiantly removes her dress and undergarments piece by piece as the other partygoers sit on either side of the pool and watch. A sudden halt in the song playing—Phil Harris’s jaunty “The Thing”—adds juxtaposition and dramatic tension.

The stripping is an apt metaphor for Jacy’s emerging sexuality, a gesture in which “bravado covers up sheer terror,” notes Shepherd in her memoir, Cybill Disobedience. Teetering as she unhooks her bra, Jacy loses her balance and has to sit down on the board. Behind the bravado we glimpse a palpable vulnerability, but also an ownership of her body and its power as she gains acceptance into this crowd by shedding her inhibitions. When the host’s little brother surfaces just beneath her, Jacy, gaining confidence, yanks off her panties and tosses them onto his scuba mask before sliding into the water. The onlookers cheer as they join her in the pool, the party ramping back up.

Jacy looks triumphant as she comes up for air, wiping the water from her eyes as Frankie Lane’s “Rose, Rose, I Love You” starts to play. The scene also marks the passing of the baton of her affections. She looks at her wrist, realizing she forgot to take off her watch—a Christmas gift from Duane, whom she has designs on ditching. She shakes it and puts it to her ear, but the watch has stopped. Catching eyes with the host, Bobby Sheen (Gary Brockette), a country-club type who seems to her a better romantic prospect, Jacy shrugs and gives him a coy smile.

Released 20 years after it was set, The Last Picture Show was part of an early-1970s nostalgia for the 1950s. The musical Grease, also about high-schoolers in the 1950s, premiered the same year and became the longest-running Broadway show in history (until it was surpassed by A Chorus Line in 1983). Bogdanovich’s decision to film The Last Picture Show in black and white for depth of field, at the suggestion of Orson Welles, adds to the retro effect. A diegetic soundtrack mainly of country tunes such as Hank Williams Sr.’s “Cold, Cold Heart” and “Why Don’t You Love Me” places us in the era and subtly comments on the action.

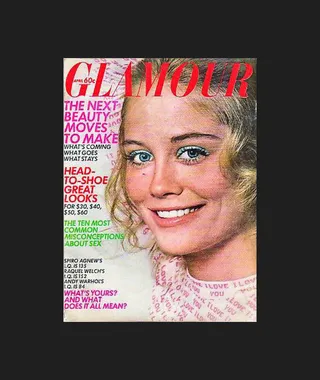

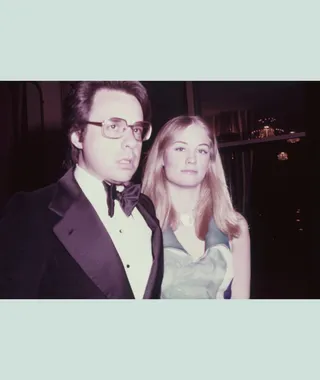

From left: Cybill Shepherd on the cover of Glamour, April 1970; Peter Bogdanovich and Cybill Shepherd, 1975

“Bogdanovich’s decision to shoot in black and white makes the nudity feel more provocative.”

Filmed at the height of the sexual revolution, when movies such as The Graduate and Midnight Cowboy were reflecting changing sexual mores, Bogdanovich’s decision to shoot in monochrome makes the nudity feel more provocative. The Hays Code–film industry guidelines that dictated “acceptable” content from 1934 to 1968–would have been in effect during the period in which the story was set. By way of comparison, in the book, a character gets excited to see Ginger Rogers in her slip in the 1950 film Storm Warning, so The Last Picture Show’s pool scene is cranking it up a notch. Jacy’s nervy yet liberating disrobing stands in sharp contrast to the 40-year-old Ruth (Cloris Leachman), who is so nervous in a later scene about undressing in front of her young lover, Sonny, that she does so only under the bedsheets.

Despite having no acting experience, Shepherd was cast in the role after Bogdanovich saw her on a Glamour cover, thanks to a “fresh sexual threat in the photograph that made him think of Jacy Farrow,” she recalls. Known as the prettiest girl in town, Jacy has to navigate the mixed messages girls in the 1950s received about their sexuality, walking a tightrope between appearing too easy and too uptight. She adroitly manages negotiations with Duane about how far he’s allowed to go and their peers’ impression of what’s happening between them. While she uses sex for status more than pleasure, Jacy nonetheless shows agency—manipulating men to get what she wants.

In a frank conversation that would have also breached the Code, Jacy’s mother, Lois (Ellen Burstyn), offers to get her birth control, suggesting she sleep with Duane in hopes that she’ll get bored quickly and “find out that there isn’t anything magic about him.” Unhappily married to an oilman, Lois wants to prevent her daughter from falling into the same trap of getting pregnant and marrying young. A scene cut from the theatrical release and reinstated in the 1992 director’s cut shows Jacy having sex on a pool table with Abilene (Clu Gulager), Lois’s lover. While the sex is consensual—it’s Jacy who brings about the encounter—the experience is not pleasant. Despite their mutual betrayal of her mother, Abilene’s icy manner and the way he discards her in the aftermath (not to mention their power differential) make Jacy more sympathetic to the audience.

From left: Midnight Cowboy, dir. John Schlesinger, 1969; The Graduate, dir. Mike Nichols, 1967

The fact that Bogdanovich was having an affair with Shepherd on set while married to the film’s production designer, Polly Platt, adds another level to the male gaze on Jacy’s nude scenes. (Bogdanovich would leave his marriage and two young daughters for what would be an eight-year relationship with Shepherd.) Although the pool scene was filmed with a skeleton crew, Bogdanovich’s recollections in the 1999 documentary The Last Picture Show: A Look Back indicate why the Screen Actors Guild now recommends the use of intimacy coordinators.

In another experience all too common for actresses who had done nude scenes, Playboy repeatedly approached Shepherd, offering her up to $50,000 to pose nude. When she refused, they published frame enlargements from The Last Picture Show without her consent in the November 1972 Sex in Cinema issue. The resulting lawsuit she took out against the magazine ended in a settlement and the introduction of a clause in the standard SAG contract requiring an actor’s written permission to print a nude still—protection that held well for print publications but has proved impossible to police online.

With its portrayals of premarital sex, adultery and closeted homosexuality—all of which the midcentury Kinsey Reports had shown to be more prevalent than admitted—The Last Picture Show no doubt hit uncomfortably close to home in towns across America. That the iconic pool scene still resonates more than 50 years after its release and 70 years after it was set suggests that Jacy’s “strip show”—in all its tenderness and temerity—captured something absolutely timeless.