The Accidental Screenwriter

By Tama Janowitz

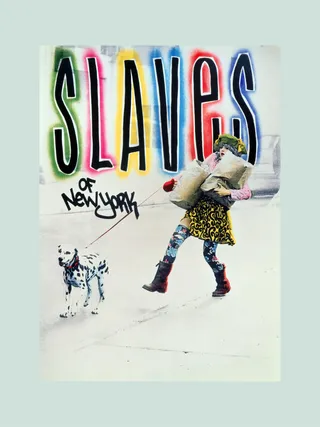

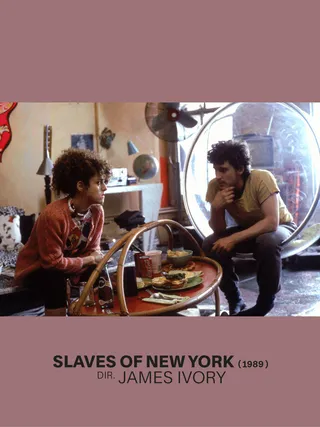

Slaves of New York, dir. James Ivory, 1989

The accidental screenwriter

Tama Janowitz remembers the wild ride of turning her best-selling short-story collection, Slaves of New York, into a Merchant Ivory film

By Tama Janowitz

July 23, 2024

Life is not happening to you when you write. Whether it’s a novel, nonfiction or short stories, you are by yourself, totally alone with a blank screen. Or, as in my case when I started writing, typing on a manual typewriter. (Later, in 1994, I would appear in a print ad for Steve Jobs’s PowerBook computers.) Typewriter or computer, whatever happens, it’s not real, it’s stuff you’re making up—or guessing at—in your head.

![]()

Tama Janowitz on the set of Slaves of New York, 1988

![]()

A poster for Slaves of New York

Making a movie, on the other hand, is collaborative. There’s a director, an assistant director, a continuity person, a set designer, a still photographer, etc. Instead of imagining someone in your head, there are actors—real people, saying lines—in an actual place. If, as the scriptwriter, you’re encouraged to be on set, you become a participating bee in this cinematic beehive, no longer making up stuff in an apartment—which, in the early 1980s, I measured at 13 by 10 feet, a little bigger than a jail cell.

Before Merchant Ivory made a film based on my 1986 short story collection, Slaves of New York, Andy Warhol had purchased the rights to my stories. It was going to be the first film he had made since Bad (directed by his boyfriend, Jed Johnson, 10 years earlier, in 1977). Andy didn’t want to buy all the stories in the collection, just some. I was thrilled. I had grown up watching Warhol films, starting when I was ten, when they played at the local university or the art house—Holly Woodlawn screaming at Joe Dallesandro, who was busy shooting up, overdosing in some crummy Lower East Side apartment—and Ciao Manhattan, with Edie Sedgwick lying naked in the bottom of a swimming pool. The films were funny, real and sad.

Twenty years later in New York, I was part of the Warhol realm that had been such a big influence on me. But by that time, Andy was no longer considered the cutting-edge star he had been. By ’85 his work was considered passé. He painted portraits of socialites or rock stars’ wives—on commission, for $20,000 apiece. He made silk screens for ads like Absolut vodka and TV commercials for Pontiac. An artist doing these things then was sneered at. In the city where he and I lived—New York—he was considered a has-been.

![]()

Bernadette Peters in Slaves of New York

![]()

Tama Janowitz and Bernadette Peters in Slaves of New York

Andy said he would pay me $5,000 for the story rights. Or he would give me one of his paintings. I had nowhere to live and no income. “What about…could you rent me space in one of your buildings?” I asked.

“No,” he said.

I would have preferred a painting, but…what was I supposed to do, walk around homeless, carrying a Warhol canvas under my arm? Five thousand dollars would pay my rent for a long time, even though I was never lucky at finding a cheap place to live. I paid $900 a month, considered a lot at the time. My West Village apartment was a former meat locker, once used for aging steak. During January and February, when the hot water gave out, rather than fix it, my landlord reduced the rent to $450.

If I had taken a painting? A self-portrait by Andy—one of his last paintings to be shown during his life—went at auction for $27.5 million in 2011. Instead, I took the $5,000.

After Andy died, Merchant Ivory (A Room with a View, The Remains of the Day) bought the rights to the stories from Andy’s estate, along with the rest of the collection. Filming began in April 1988. James Ivory was the director, Ismail Merchant a producer. They had been making films together since 1961. I wrote the screenplay with Jim in the kitchen of the mansion he was renovating a couple hours north of the city. He helped me every step of the way and wrote a great deal of it as well. I was privileged, but it was still agony—I had already written the stories, and rewritten them, and proofed them so many times that I couldn’t stand them. Plus, they were separate stories, with individual trajectories and endings. To find a way to combine them and create some overall plot was impossible.

I got to sit in on casting sessions. Being an actor appeared humiliating to me. Famous or unknown, all had to come into an office and, mostly, get rejected. The casting director had power. He kept telling Jim to “take another look” at some actor who was “going to be a big star.” The casting director was the one deciding whether an actor even obtained an audition. One actor (who wasn’t suited for the role) threw a temper tantrum when Jim thanked her for her time. “I was told I have the part!” She was furious, voice raised.

“Who told you that?” Jim asked. “I’m the director!” He sounded hurt. The actor shouted something about legal action and stormed out of the room.

Eventually, Bernadette Peters agreed to the role of the lead. We had met with so many female actors, who came to the audition because they were considered hip and downtown, or who tried to disguise themselves by dressing in clothes they thought were cool or sharing the information that they’d been a drug addict. Bernadette, with her wild curls and cherubic expression, was a lot more of an authentic downtown NYC character. We shared friends and acquaintances. She was worshipped by gay and nongay fans of disturbing Stephen Sondheim musicals.

“If, as the scriptwriter, you’re encouraged to be on set, you become a participating bee in this cinematic beehive.”

Bernadette coached me when I had scenes in the film with her. I played the role of Abby, the best friend who lived in Boston and needed her advice. In one scene in a bathroom, there was nowhere to sit, so I sat down on the toilet seat. It was normal behavior for women and seemed right for my character. I didn’t realize there had never been an American film before where a woman sat on a toilet seat. I heard Jim laughing in the background. But he didn’t correct my choice. It was 1988. Now in half the films I see, some girl is sitting on the toilet seat. We filmed that scene in a loft, and I was having issues with my lines. I realized, though, there was no one to complain to. After all, I had written them.

The movie was low budget. Five million, I think. Filming around NYC and on the Lower East Side was difficult. Drug addicts and the homeless often ruined shots. But the footage was real.

For one scene, Stephen Sprouse, the fashion designer, reenacted one of his shows. It had originally been staged at the World—on East 2nd Street near Avenue C—in a former catering hall. The sequence is a historic re-creation for the movie.

There was a scene filmed at Pat Hearn’s art gallery (Pat had played in a rock band and acted), in the bombed-out East Village. There were squatters living in the wrecked buildings beside the gallery, leaning out to watch. Pat was horrified about renting out her elegant gallery as a movie set, but needed the money too badly to turn the offer down.

A scene in a taxi: Jim, the cinematographer Tony Pierce-Roberts, Bernadette and Adam Coleman Howard (playing a graffiti artist) had to go around the block all afternoon to get the shot, crowded into the Checker cab. On the sidewalk was a dead body. A real dead body. It didn’t move all day—nor did the police or an ambulance arrive. Every time the taxi circled back, they passed the corpse. At least there were no continuity issues.

I always thought that the actors were overacting in most movies and talking in a dramatic way that wasn’t at all the way real people spoke. I just wanted to say my lines, the same as actual people say them to each other without all that extreme emotion. Then again, during one lunch break, the cinematographer and the movie’s hairstylist got into a fistfight. I missed it, though, and never did learn the reason for the scuffle.

From left: Tama Janowitz and Andy Warhol at a party celebrating her book Slaves of New York; a poster for Bad; a film still from Bad

Another scene, where I appeared opposite Bernadette, was in a Lower East Side hair salon. We were getting our hair done and discussing the New York City apartment situation. I thought it was odd that the singer Michael Bolton had been hired to play the hairdresser—but nobody had informed me in advance. Now, suddenly, he appeared, standing behind my chair in the salon, putting metal shish-kebab spikes in my hair. I didn’t want to say, “Yo, how is it that Michael Bolton is fixing my hair?” It seemed unlikely, but then I didn’t really know who Michael Bolton was. I didn’t find out until later that I had been hallucinating—it was an actor named Anthony Crivello.

Jim always had a sixth sense for casting. He was often the first to cast unknown or nearly unknown actors who later went on to become major stars. There were all kinds of great actors in this film. Steve Buscemi, Mercedes Ruehl, Stanley Tucci, Madeleine Potter, Maura Moynihan. There were drag queens singing the Supremes, and a scene in the far West Village, at the club Siberia, in what was then a working meat market. Blood, fat and bones covered the cobbled streets.

The Standard, High Line hotel—a couple of blocks up—didn’t exist back then. No fancy shops, few restaurants. There was a basement bar nearby called the Mineshaft. I didn’t want to go there, not after what I heard, even though my meat-locker apartment was right nearby. And yet, by 1988, when Slaves of New York filmed, it was already a different era of New York than the one I had described in the book. My stories, written from 1978 to 1985, were set in a city that was rougher. Not by much. But in the early ’80s, below 14th Street, life was wilder.

After the filming and editing, Ismail, Jim and I traveled to press conferences, interviews, magazines, TV shows. We waited in the greenroom with the other guests—including Evel Knievel and his son Robbie. “Those are the weirdest people I have ever seen!” Evel said, staring at us before he went on air to talk about jumping across canyons on flaming motorcycles.

Each morning, before departing for the next city, the newspapers were delivered. In DC, Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco, the reviews were uniformly negative. I felt responsible. It had to be my fault that everybody hated the movie so much.

I never got another offer to write a film. Any script I wrote, my various agents didn’t bother sending out. But 35 years later, Slaves of New York still shows at festivals, art houses and university theaters.

![]()

![]()

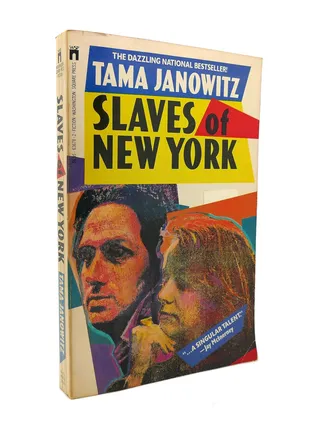

The Washington Square Press edition of Slaves of New York, 1987

When it came time to edit the footage, Jim added in some split-screen scenes as an homage to those Warhol films that I loved. I don’t know what kind of movie Andy would have made out of my stories. He died in 1987, at age 58, a year after acquiring the rights. But Andy was looking after me—wherever he was—by sending Ismail Merchant and James Ivory to make that film. Being a part of that process was among the best times of my life.