The Bard of Menomonee Falls

By David Weinberg

American Movie, dir. Chris Smith, 1999

The Bard of Menomonee Falls

Reflections on a pilgrimage to meet the star of American Movie

By David Weinberg

November 15, 2023

Chris Smith’s 1999 documentary American Movie opens with a 30-year-old man delivering newspapers before dawn in Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin. A voice-over narrates: “I was a failure and I get very sad and depressed about it and I can’t be that no more.… Now I’m back to being Mark, who has a beer in his hand and is thinking about the great American script and the great American movie.…This time it’s most important not to fail, just to drink and dream, but rather to create and complete.”

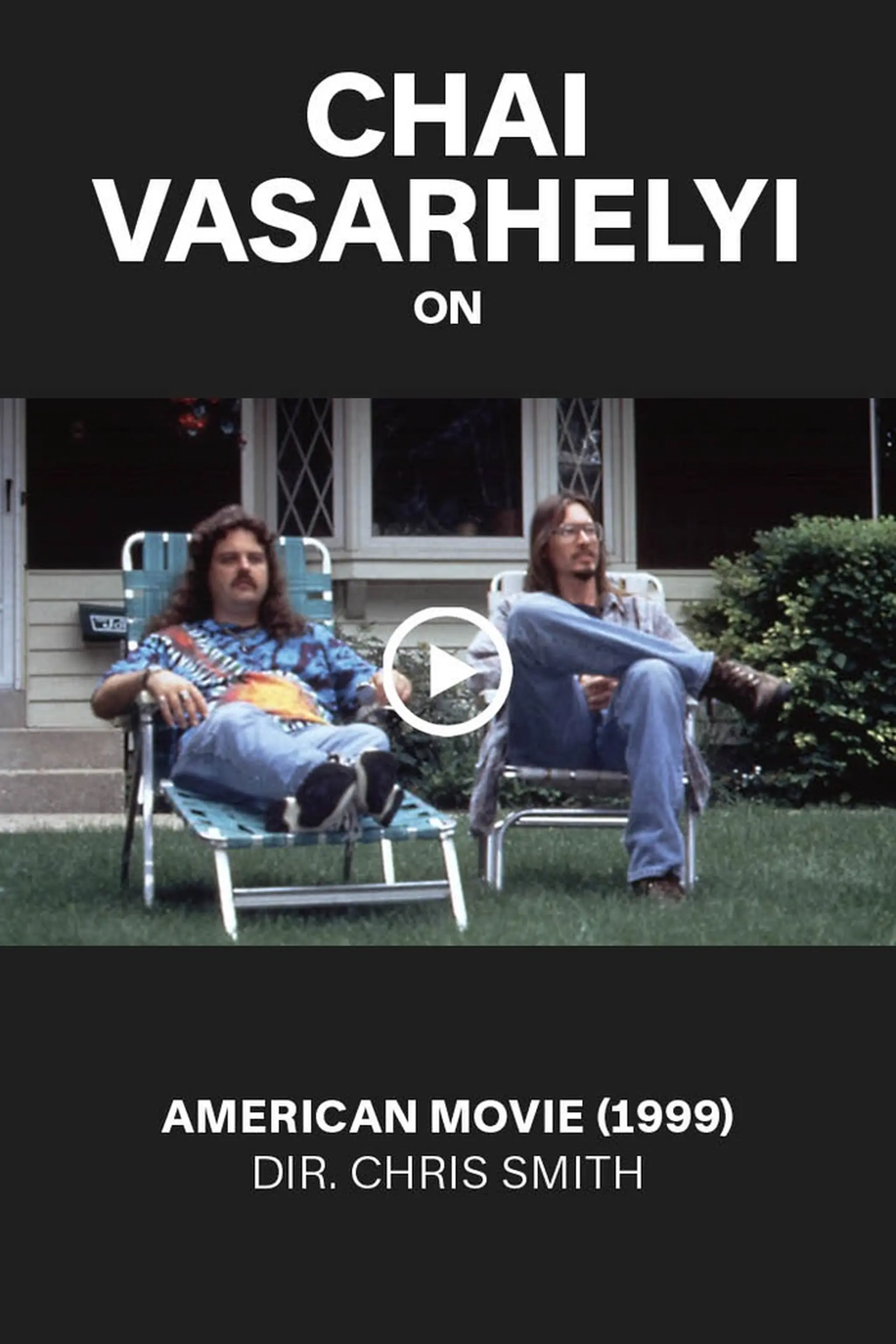

From left: Uncle Bill and Mark Borchardt; Mark Borchardt

This is our introduction to Mark Borchardt, a long-haired, lanky dreamer with a Wisconsin accent as thick as his glasses. A broke amateur auteur, he is hell-bent on making a feature film with a budget of essentially zero dollars. Borchardt lives with his parents, is riddled with debt, and struggles to keep up with the child support for his three kids. When he’s not working a day job, he’s focused on writing and directing a black-and-white feature film called Northwestern, a boozy life-and-times portrait of working-class anomie set under the gray skies of Wisconsin.

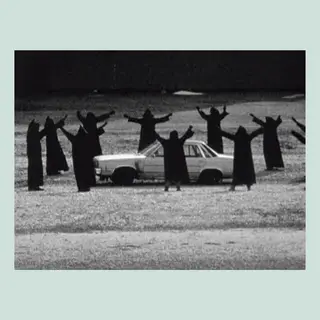

American Movie abounds with oddballs and outcasts. In a bit of convoluted logic, to raise money to finance Northwestern, Borchardt decides he must first make a horror short called Coven, enlisting friends, family and locals as cast and crew. These include his best friend, Mike Schank, a soft-spoken guitarist who’s newly sober after a decade-plus of hard partying, and Borchardt’s uncle Bill, a frail retiree who lives in a trailer and whose alternately affectionate and coercive (but always hilarious) rapport with Borchardt gives American Movie some of its most memorable moments.

American Movie trailer

When Borchardt isn’t shooting, writing or drinking, he works as a groundskeeper at a local cemetery to support his art. In one scene, as he removes and folds 1,400 of American flags that have been placed on graves, Borchardt recounts the indignities of his job in an anecdote about cleaning the cemetery bathroom. “I had to clean it up, man, but before that, for about 10 to 15 seconds, man, I just stared at somebody’s shit, man. To be totally honest with you, man, it was a really, really profound moment. ’Cause I was thinking, I’m 30 years old, and in about 10 seconds, I gotta start cleaning up somebody’s shit.”

As someone who cleaned shit for a living, I could relate. In 2001, I, too, had artistic dreams with no clear plan to convert them into reality. I wanted to tell stories on the radio, but I didn’t own a tape recorder or a computer and had recently been kicked out of college for throwing too many loud parties. I had moved to Fort Collins, Colorado, where my friend—also named Mark—attended Colorado State University, and had gotten a job as a janitor, cleaning the dorms. I got into trouble, spending 30 days in jail for driving on a suspended license. Rewatching American Movie with Mark during this period, I saw a working-class dreamer with ambitions to transcend his increasingly claustrophobic existence. He reminded me of a lot of my friends.

I don’t remember whose idea it was to drive to Menomonee Falls and find Borchardt, but Mark and I decided to make a pilgrimage to consult the oracle himself. Borchardt had pursued the creative life on very little means. How did he do it? How do we do it?

We borrowed Mark’s dad’s minivan and headed east. The full extent of our plan was to look up Borchardt in the phone book once we got there. I suppose we figured he’d greet us at his front door and welcome us as superfans. We rolled into town early in the morning and set out on foot in search of breakfast. Menomonee Falls had a small-town vibe. As we turned a corner of an otherwise empty street, right there on the sidewalk—miraculously (or predictably)—was Mark Borchardt himself, sitting at a card table, banging away on a typewriter. In that moment it felt like God had set him there before us.

From left: filming a scene from Coven; Mark Borchardt addresses the camera

“We drank 100 beers with Borchardt and his friends that day. We slept on his floor, and in the morning, Borchardt and his mom gave us a tour of Menomonee Falls.”

We explained that we had driven from Colorado to find him. He politely declined our offer of breakfast, saying that he had just vomited and he had some writing to do. But he told us to come back and find him after we ate.

This is how we came to spend a day sitting on the stoop, drinking beers with our hero. Mike Schank came over too, along with other friends who’d gotten word about the kids from Colorado with ample beer money. I couldn’t tell you what we talked about. Mark and I just sat there in awe. I have a few flashes of memory: sitting at a table, listening to Mike play guitar. Mike doing push-ups on the sidewalk. Sitting on Borchardt’s couch, watching him watch a Green Bay Packers game on TV. I felt like I was in a scene from American Movie.

We drank 100 beers with Borchardt and his friends that day. We slept on his floor, and in the morning, Borchardt and his mom gave us a tour of Menomonee Falls. It was one of the greatest weekends of my life up to that point.

In American Movie, Borchardt does eventually finish Coven, and American Movie ends on a note of triumph: Coven premieres in a theater and a proud Borchardt introduces the film in front of a packed house of friends and family. A postscript informs us that Bill died shortly after production, leaving Borchardt $50,000 to finish Northwestern.

A few months ago I called Borchardt to interview him for a story. It’s been 26 years since the local premiere of Coven, and Northwestern remains unfinished. The only film Borchardt has directed since, besides a couple music videos, is a short documentary, The Dundee Project. He had no recollection of my visit in 2001, nor did he seem to care that I had been so enamored with him that I had driven across the country to meet him. These days he doesn’t like to talk about American Movie. Perhaps he feels like fans were laughing at him instead of with him, or the film is an unwelcome reminder of abandoned dreams. In one scene, Borchardt is watching old footage of his opus and Smith asks him why he stopped working on it. Borchardt replies, “I think obviously there’s gotta be some fear, like if you actually go ahead and do it and complete it, there’s more consequences to it.”

While Borchardt has struggled to make his own films, Chris Smith has built a successful career, directing several well-received documentaries as well as executive-producing the massively successful Netflix series Tiger King (2020–2021). American Movie, meanwhile, has become a cult classic and a source of inspiration for a generation of filmmakers and artists. In the hands of a lesser director, Borchardt might come off as a hopeless romantic, but Smith elevates his subject without glorifying him. Yet it’s Borchardt and his quotable wisdom and folly that make American Movie so unforgettable.

It only occurs to me now that Smith probably would have been a better person to seek for professional advice when I was young. He was a professor back then; Borchardt had been a student in his class. But I doubt Chris Smith would have drunk 100 beers with us and let us sleep on his floor.

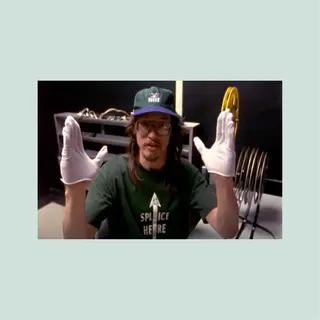

Mike Schank plays guitar blindfolded

A few years after the trip to Menomonee Falls, I made a similar pilgrimage to the home of the journalist who inspired me to get into radio. By then I had come to the realization that hard partying and ambition are not very compatible. It took me a while but eventually I taught myself how to make radio stories and slowly built a career that doesn't involve cleaning toilets. I became a voice on the radio. I got sober. But having a little more perspective doesn’t diminish my urge to root for Borchardt, and for all the underdogs with overdrawn bank accounts fighting their demons and circumstances.

As for Borchardt, he remains steadfast in pursuit of his next film (he’s written a dozen screenplays since making Coven). When we spoke recently, he rattled off his influences: “Ingmar Bergman and Orson Welles, Fassbinder and Herzog and Wenders and Polanski and Cassavetes and all of that.” When I asked if he found it daunting trying to make films without any financial backing, he scoffed. “The only obstacle in filmmaking or in art is yourself,” he said. Sure, he conceded, you do need some resources, “but you need yourself first. Without your own belief in your own confidence you have nothing.”