The Body Politic: Audrey Diwan

By Lisa Rovner

The Body Politic

Happening filmmaker Audrey Diwan on abortion,

desire and inhabited silence

By Lisa Rovner

February 23, 2023

Audrey Diwan didn’t set out to make a political statement, but her critically lauded abortion drama Happening—winner of the Golden Lion award at the 2021 Venice Film Festival—arrived stateside at a pivotal moment for reproductive rights: Roe v. Wade was overturned the following month. As Diwan prepares to explore the flip side of female sexuality in a remake of the softcore classic Emmanuelle, with Noémie Merlant in the title role, she sat down with filmmaker-artist Lisa Rovner (Sisters with Transistors) at a Paris café to discuss the female gaze, storytelling that transcends gender, and the political stakes of personal choices.

Audrey Diwan

I love how your film Happening opens: a black screen, a girl’s voice: “Can you help me?” After watching it, I was desperate to do something, to help. The film feels like a call to arms. Do you see yourself as a political filmmaker?

I don’t conceive my films as political manifestos, but I think there’s a strong connection between the intimate and the political. Women resort to clandestine abortion because of a law that dictates whether or not they’re free to have an abortion, but at the onset of their journey there’s a sexual relationship. So it all begins with something immensely intimate and culminates in a political decision. I think that a lot of intimate decisions people make are ultimately connected to a political thread, and I love being aware of that, but I’m not trying to create a political discourse out of it. What was important to me, what I was attracted to in [2022 Nobel Prize in Literature winner] Annie Ernaux’s book, Happening, was the protagonist, Anne.

Portrait of Happening author Annie Ernaux

What is it about Anne that spoke to you?

What interests me in the book is the way this young woman asserts her intellectual and sexual desires, such as the desire to break away from her social class to attend the bourgeois university. The journey she embarks on is a journey toward freedom. On that journey she must face clandestine abortion and that’s where it all becomes political, even though everything else I just mentioned can also be regarded as political. So for me, the intimate and the political are truly interwoven. But at the end of the day it comes down to a storytelling question. Do you want to make a manifesto film, or do you want things to become political through what you create? I tend to favor the second approach.

French lawmakers just voted against inscribing the right to abortion in France’s constitution. In the States, the Supreme Court recently overturned the constitutional right to abortion, and the procedure remains banned in 24 countries. Sharing Anne’s story feels vital right now.

I know there was a debate [in the French Senate], but I don’t think it's been decided yet. In any case, I find these measures to be sadly superficial. I mean, look at what just happened in the United States. The constitutional right to an abortion [under the 14th Amendment] was supposed to protect women, but as we know too well, inscribing a law in the Constitution doesn’t guarantee its permanence.

This film is so much about silence and breaking it. The writer Rebecca Solnit says that “Silence is the universal condition of oppression,” and argues that “Liberation is always in part a storytelling process.”

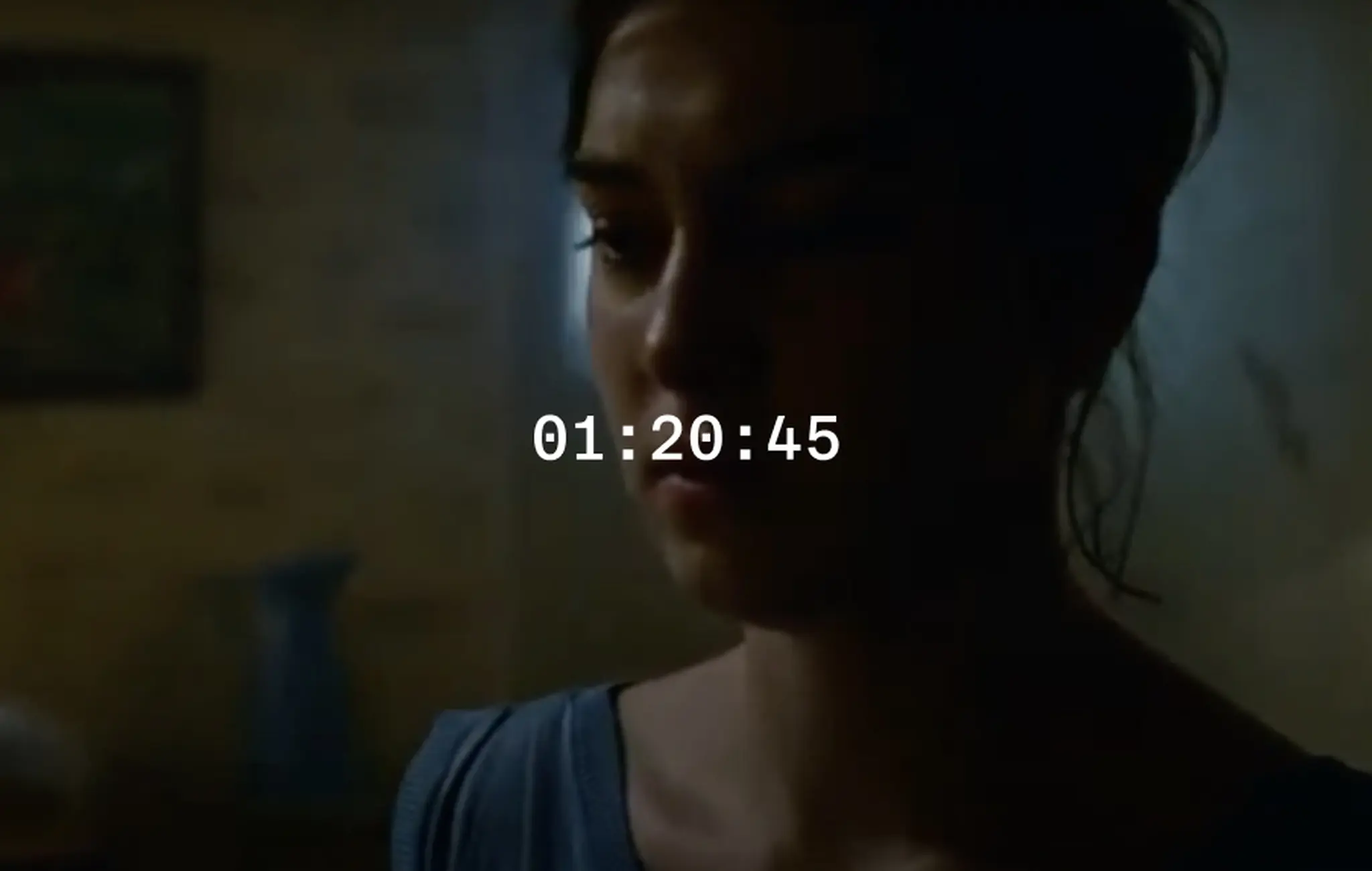

I love talking about silence. I used silence as a narrative tool. Silence plays a major role in the film, and the actress Anamaria Vartolomei and I worked hard to make her silent moments meaningful.

How did you and Anamaria prepare for all the silent scenes?

In her book, Annie Ernaux writes that the character’s mind was constantly occupied. So Anamaria and I wrote interior monologues, like obsessive phrases which she repeated to herself while acting those silent scenes. It’s an inhabited silence.

What’s interesting about Annie Ernaux’s process is that she depicts silence by working against it. She sculpts this story to rescue it from silence, as it were, all the while employing devices, like the semantic field of silence, to describe it. Silence is obviously an instrument of power. When you don’t have the words to express what you’re going through, you cannot open a debate that will allow things to change. At the time [1963], no one could even say the word abortion.

![]()

Fabrizio Rongione and Anamaria Vartolomei in Happening

You’ve talked about how difficult the illegal abortion was to portray, as it’s something that exists in the shadows.

When you arrive at a clandestine abortionist’s, you don’t know who she is. It’s all based on anonymity. She’s not supposed to know who you are, and you’re not supposed to know who she is. So that if there’s a confrontation with authorities, you can’t denounce each other. Yet this perfect stranger is the person with whom you’re going to share the most intimate moment of your life, because if the procedure fails, you die.

Anna Mouglalis brought a quality of witchcraft to the role. Her performance has something of the mystery of witchcraft. We don’t really know where we are; we don’t understand the nature of this place. We can see that it’s an apartment that’s been reconfigured to serve another purpose, and then there’s this mysterious figure, whom I thought Anna embodied brilliantly.

I read that Mouglalis, who plays the abortionist, did extensive research ahead of filming and hunted down actual period instruments. What was your collaborative process?

When I work with an actor, I look for an intellectual partner. [Mouglalis] is an actress with a committed feminist stance. We bring our references to the table and select those that suit us both to create a common language. And yes, Anna brought instruments with her to set, and it was extraordinary. What’s also extraordinary is how difficult it was to find the right instruments, because they haven’t been studied or referenced much. For example, the book talks about “a probe,” which became a whole ordeal because we couldn’t understand what it was. We knew it was a repurposed medical object but couldn’t figure out which one. Diéné Bérété, the production designer, was in touch with a medical school and a medical museum to find that object, but it eludes history. Again, the idea of silence.

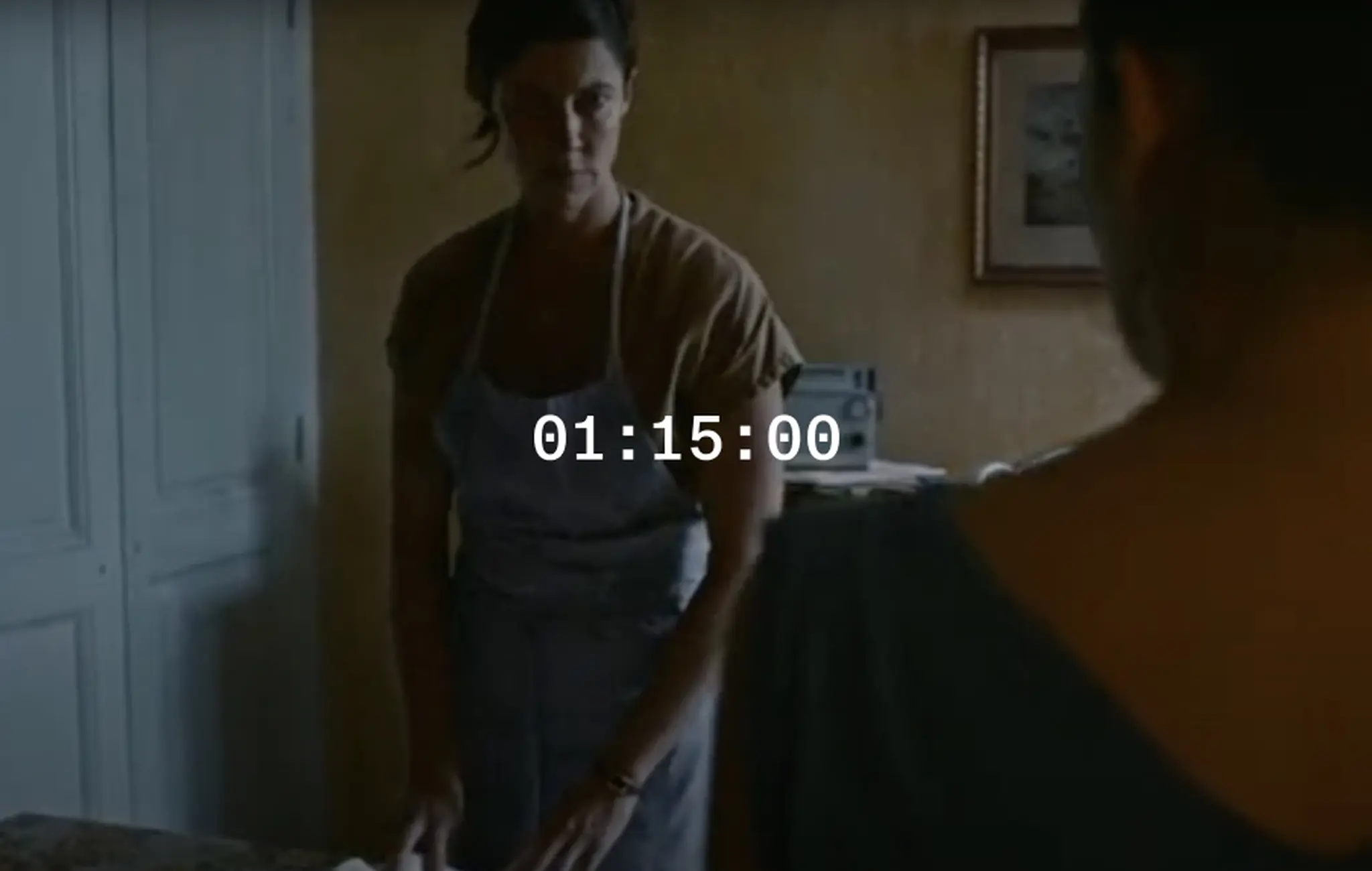

You have said, “The idea was to focus on her body and not the setting [...] so that we’re not watching Anne but rather become her.” Can you elaborate on how you went about achieving this?

Most of my choices stem from the book. There were a few sentences that haunted me, like when Annie Ernaux writes that it’s an experience that’s lived from one tip of the body to the other, which obviously includes the mind. I love working with actors on their bodies, on the way the body can convey thoughts and become a narrative tool. The body is not merely an object to look at; it drives the story. So many things can be perceived through the body, including someone’s relationship with their social class, their emotions, their feelings.

I said to Anamaria, “Let’s try to find Anne in the body: How does she put her feet on the ground, how does she hold her shoulders, what’s her gaze like?” I would tell her, “For me, she’s not someone who smiles, she’s not pleasant.” I love characters who don’t try to be pleasant and end up becoming so, which is why I suggested Anamaria watch the Dardenne brothers’ Rosetta. I said to her, “Rosetta has her gaze set on the horizon, as though she were the only one who could see it.” Then, as we started finding Anne in the body, I said to Anamaria, “She reminds me of a soldier,” and she replied, “Yes, that’s it.” So we gradually developed this idea of the soldier going through a battlefield, which allowed us to find Anne’s internal rhythm, the rhythm of her walk, her tension, her way of always being in a state of alert, etc.

![]()

Anamaria Vartolomei in Happening

Can you talk about your work with the DP, Laurent Tangy, and how your choices reflected Anne’s experience?

We decided to start the film with an inclusive frame. When Anne is among the other girls, the frame is wider. The world around her is more tangible, but we can still feel her solitude in the image. Then we start positioning ourselves behind her and moving with her. So when she opens the door and steps into the clandestine abortionist’s place, we open that door with her. It makes us identify with her even more, because we feel like we’re her as she opens that door without knowing who’s on the other side.

This is heightened by the choice of the frame, which is almost a square, with an aspect ratio of 1.37. Since the frame is not lateral, we don’t see the supporting characters arrive—they just appear in the shot. The protagonist is in a paranoid state, afraid that someone might discover her secret. Having characters appear out of nowhere keeps us on the same level of tension as her. We identify with her fear of being stared at by others, and not being able to see where people come from accentuates that paranoid sensation.

One of the distinguishing features of Happening’s cinematography is the focus pulling.

The focus is a narrative element in and of itself. Before the shoot, I wrote the focus puller, Jean-Christophe Allain, a 35-page document detailing all the focus changes. When Anamaria turns her head, what she looks at allows us to guess what she’s thinking. If she turns her head and there’s a quick focus change, her gaze is curious, intense, worried, whereas if she turns her head in a relaxed mood, there’s a slower focus change. That was the choreography we established every morning.

During the abortion, we had to determine when the focus would be on the clandestine abortionist, and when we would dive back into the protagonist’s sensations, her pain. We rehearsed so well that we didn’t cut at all during the first take—it lasted seven and a half minutes. I said to the actresses, “Don’t worry. Next time, we’ll cut. We’ll do it in two takes,” but it ended up being a long take every time. The scene imposed itself on us.

Even though the film is set in 1963, because of the camera work it feels nothing like a period piece.

What I wanted to portray was the eternal present of this unfortunate story.

.jpg)

You’ve spoken of how you and Anamaria identified with the film’s protagonist: “We both knew what it’s like for a woman to legitimize herself when you don’t come from an artistic family—to be bold enough to say, ‘One day I want to write, I want to act.’”

I recently saw The Super 8 Years, the film that Annie Ernaux and her son David made with their family’s home movies. It’s interesting because she speaks in voiceover over the images, some of which date back to when she was in her early thirties. Over an image of herself she says something like, “This woman is carrying a secret. She seems to be with her family. But really she's thinking about the book she's been writing in secret.”

Ernaux published her first book when she was 34. Her book had to be published before she could admit that she’d been writing. Her act preceded her ability to pronounce those words. That’s the social dimension of Happening’s protagonist, too, what prevents her from speaking her truth.

One thing struck me though in your adaptation of the book is that you cut the bit about the fellow student lending Anne the money. In the film, Anne pays for the abortion by selling everything she owns.

What I found moving about that was the idea of dispossession—the fact that she relinquishes everything that belongs to her body in order to save her mind. She sells her books, her baptism jewelry. Suddenly, she must choose between her body and her mind, and she’s ready to sacrifice that body, even to die, to have a chance to save her mind—her mind being her intellectual future. She says, “I’d like a child one day, but not instead of a life.”

I wondered if it was a subtle way of portraying “sisterhood” as complicated.

It’s not that there’s no solidarity, it’s that everyone is crushed by a deep fear of ending up in jail. Also, let’s not forget that the young women around her come from working-class backgrounds, that they are the first generation in their family to have access to higher education, at the cost of so many sacrifices by their parents. So if they get expelled from the university, their future goes to waste, along with all of their family’s hopes and sacrifices. There’s immense social pressure. In no way was I judging those characters—I understand very well the reasons for their behavior.

In France, there seems to be a robust sisterhood among female filmmakers. Can you talk about Le Collectif 50/50, the initiative that lobbies for equality within the French film industry?

I became very interested in Collectif 50/50 when it was born [in 2013]. I was interested in its ideas and especially in the questions it posed, including those about the formation of a crew and the accession of young female technicians to leading positions. I participated in some of their meetings and heard young female DPs say, “We’re struggling to find work as DPs because there’s an old-fashioned fear that women won’t be able to carry a camera throughout the whole shoot.” So on my first feature, Losing It [2019], I had a crew with a lot of women, many of whom were starting out like me. My first assistant director had never been a first AD; my production designer had never been a production designer; and on Happening, my production manager had never been a production manager.

For the first time in history, female filmmakers hold all the biggest trophies—Chloé Zhao, Sian Heder and Jane Campion at the Oscars; Julia Ducournau at Cannes; Carla Simón at Berlin; you at Venice. How do you feel about the current state of female filmmaking?

We’re living in a very ambivalent moment. Although there are more and more female filmmakers out there, the numbers are not rising that quickly. For example, in Europe, only 25 percent of films are directed by women. Something is changing, but there’s no real equality yet. International festivals have recognized us, but we’re still facing a lot of resistance. My dream is that we transcend the question of gender.

When I was at the Venice Film Festival this year [as a jury member], [jury president] Julianne Moore was asked a question about female directors winning again. It was the third year in a row that a woman won the highest prize in Venice. Julianne replied, very cleverly, “I think it’s time we move on to the next question.” That’s also what I’m hoping for.

You have a very nuanced relationship with the term female gaze. Tell me why.

The term female gaze has conquered the public sphere. I initially thought it was wonderful because it pointed out a missing piece to understanding our culture. But when I was in Venice with Happening and people kept talking to me about my “female gaze,” I realized that the meaning of the word had been distorted—that the implication was that I had made this film because I’m a woman. So I tried to explain to the journalist in front of me that every woman wouldn’t have adapted Annie Ernaux’s book to screen the same way. Each one of us would have had a different interpretation based on our gender, but also on our culture, our life experience, our cinephilia, our tastes. Using the term female gaze in relation to my film was a way of reducing me to my gender. The term that was supposed to impose a gaze was becoming the prison of that very gaze.

![]()

Sandrine Bonnaire and Anamaria Vartolomei in Happening

Your next project is Emmanuelle. What drew you to want to remake this film?

For me, this project is a love declaration to the imaginary worlds that stimulate us, rather than a gendered willingness to revisit history. I’m a woman and I have a female gaze, which is included in all the other gazes I mentioned earlier. Of course that’s going to be felt, because I’m writing this story by projecting myself into the character, by identifying with her and imbuing her with a part of myself. Once again, it comes down to the connection between the intimate and the political. My starting point is my intimate desires, which will then evolve into an interpretation that might be political. But for me, the artistic comes first.

There is still some cultural judgment around freedom and desire, and a tendency in storytelling to limit female desire to feelings of love, excluding pleasure.

What makes me happy is to invest pleasure with imagination. I like creating stories and igniting my imagination in a pleasurable way. For the last three years, I’ve been working on abortion and pain. Now, I’d like to take a look at the other side of the coin, to explore the idea of pleasure and how one gains access to it. I think a body in search of pleasure is beautiful. I don’t think it’s trivial or reprehensible. I won’t let myself be guided by morality. I think it’s a beautiful quest in and of itself, and should be shown as such. It shouldn’t be degrading or degraded. It’s a beautiful thing to go searching for that moment of pleasure and rapture.

Translated from French by Yonca Talu