The Censored Cinema of Iran

By Khashayar J. Khabushani

Crimson Gold, dir. Jafar Panahi, 2003

The Censored Cinema of Iran

Abbas Kiarostami, Jafar Panahi and the social realists who pierced the veil

By Khashayar J. Khabushani

March 21, 2025

It’s tricky being Iranian. If you follow your lineage back—way back—it’s sometimes unclear whether you have Persian ancestry or not. Are you Kurd, Arab, Azerbaijani or Lur, part of Iran’s aboriginal peoples? Most Iranians I’ve met, including my friends and family, prefer to claim Persian identity. For them, it’s the Iranian identity that elevates one’s self-worth, connecting them to the rich history of the Persian language, arts, foods and history of a thriving empire—a history that the very last shah, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, insisted on revitalizing before he fled in exile in 1979. I think of the 2,500-year celebration he hosted at Persepolis in 1971 to celebrate the Persian Empire, and I want to ask him: How much cash did you spend on that event? (Answer: at least $100 million U.S. dollars, adjusted for inflation.) I want to tell him: That money could have been used for working-class people, to feed the mouths of hungry children and the hearts of hungry artists. Filmmakers, painters, writers, poets—how many Iranian voices left us without ever being heard, Mohammad Reza Shah?

![]()

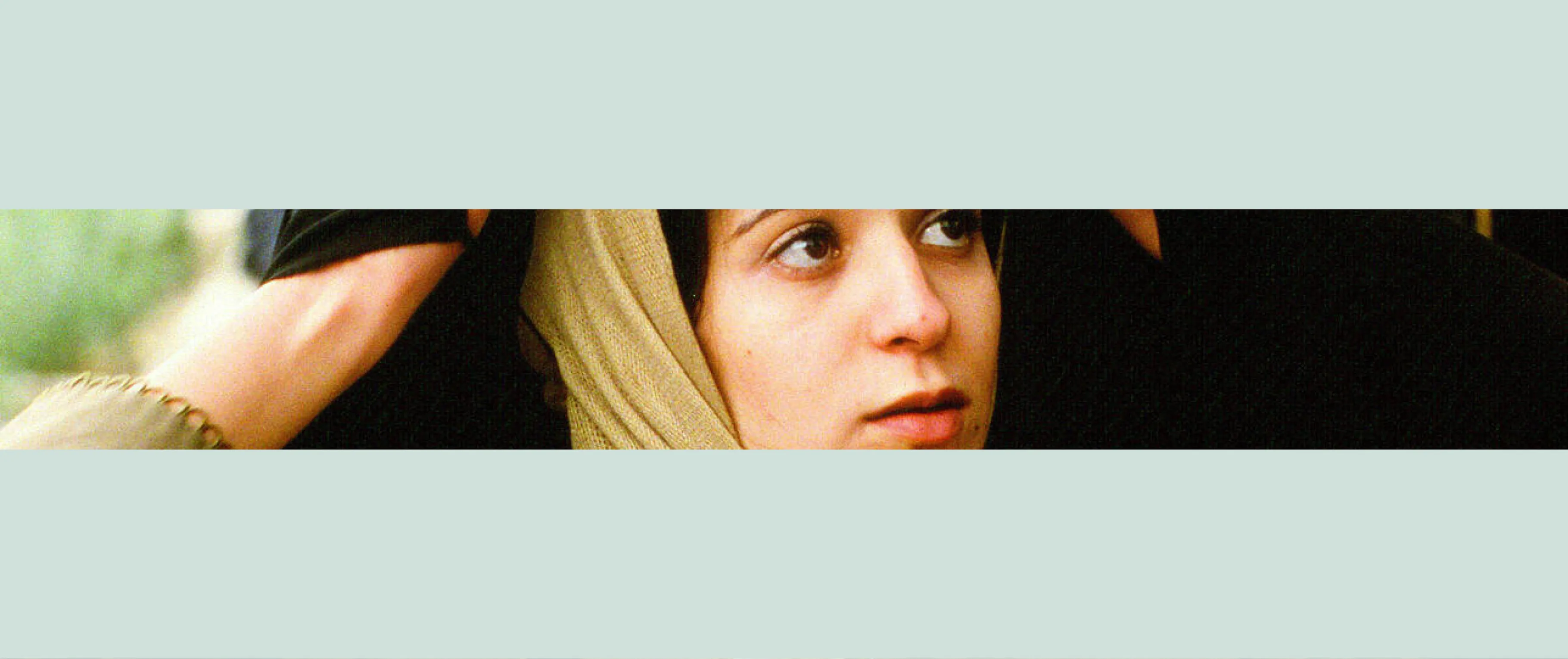

Azita Rayeji in Crimson Gold

![]()

From left: Kamyar Sheisi and Hossain Emadeddin in Crimson Gold

In Los Angeles, among those who had to flee their homes before, during and after the 1979 revolution, Persian culture and wealth, rather than the perils and beauties of Iranian life, are the main topics of conversation. I grew up surrounded by Iranians in L.A., and the majority of them, if not all, were more interested in the clothes they were wearing or the cars they were driving or the size of their homes. I’m talking about myself here too, an Iranian-American who came of age in the San Fernando Valley. Don’t get me started on the amount of times my auntie, when I was last in Isfahan, reminded me about my Persian name: “You have no idea how powerful your name is. You’re a king! A king!” Yeah, yeah, yeah. On it goes. Persians don’t take over an American embassy and don’t hold hostages captive; Persians don’t develop and hoard nuclear weapons. Shit, I don’t even think Persians pray—certainly not to a god named Allah. Iranians do all that. But also, Iranians, like the Persians, did create art.

I know about myself, in part thanks to contemporary Iranian filmmakers. Take the terrific scene in the legendary Tehran-born director Abbas Kiarostami’s 1999 drama The Wind Will Carry Us. In a dim, narrow cellar in Iranian Kurdistan, the protagonist, a journalist from Tehran posing as an engineer, whispers a Persian poem by Forugh Farrokhzad as he awaits a bowl of milk being collected from a cow’s udder by a young woman:

place your hands like a burning memory

in my loving hands

give your lips to the caresses

of my loving lips

like the warm perception of being

the wind will take us

the wind will take us.

From left: poet Forugh Farrokhzad; filmmakers Abbas Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi

Farrokhzad, an influential filmmaker and poet who challenged 20th-century Iranian norms, asks her readers to desire, love, listen and risk in a society that insists to this day on silencing women. I’ve done my best to listen as she did. Listen to the wind, the nighttime darkness, the teachings of sorrow and the surprises of happiness. Kiarostami, who worked right up until his death in 2016, passes her message along.

In one of the director’s most famous films, the 1990 crime-documentary Close-Up, he restages a real-life crime committed by Hossain Sabzian, a man struggling to find work in contemporary urban Iran. Sabzian assumed the identity of influential director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, hoping to realize his own dream of working in cinema. In the film’s final act, shot in an actual courtroom with an actual trial underway, Sabzian presents his case to the judge in the presence of the family he lied to and bilked for money, telling the court—and also the audience—the reason he chose to impersonate Makhmalbaf. He speaks slowly, softly and with conviction. He says he did so for the chance to express through art the inner experiences of his life, a life replete with deprivation and suffering, of being unnoticed by society—feelings which nobody wanted to hear about, certainly not the rich, who have ignored the needs of the poor. Food, water, shelter. He wanted art to give his own life value.

Kiarostami’s early films, made during the reign of the shah, do not achieve the same sharp provocation as his later works set during the Islamic Republic’s regime. When I watch these later films I don’t see Kiarostami perpetuating the tired myths of Persian identity—chiefly, inhabiting the world of the rich. What I see him doing is telling the truth of contemporary Iran—its beauties, challenges and corruptions—in a mode of storytelling so unpretentious and revolutionary in its honesty that it inspired an entire generation of filmmakers to follow in his footsteps.

“Panahi’s subject is the struggle of the working class, set against the hollow morality of Tehran’s elites.”

Among those heavily influenced by Kiarostami’s artistry is Iranian-Azerbaijani director Jafar Panahi, who developed an almost sibling-like bond with the maestro when he worked as his AD in the early 1990s. Panahi got his start making hard-hitting documentary shorts for the Islamic Republic of Iran’s state-sponsored television channel, but went on to become one of the most controversial filmmakers in the country, eventually imprisoned for his brash cinematic activism. Not surprisingly, when Kiarostami and Panahi teamed up to work on a film together in the early 2000s, the result was nothing short of a masterpiece. As a kid growing up in the Los Angeles suburbs playing basketball with my older brothers, the idea of Kiarostami and Panahi on the same screen was equivalent to Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant playing on the same court.

The 2003 crime thriller Crimson Gold, penned by Kiarostami and directed by Panahi, shows the brilliance of two filmmakers who have long blended high drama with brutal realism and are not afraid to break the rules of conventional cinema, including the use of nonprofessional actors. The story follows Hussein (Hossain Emadeddin), a pizza-delivery driver who, like Sabzian in Kiarostami’s Close-Up, is a man attempting to improve his lot and willing to break the law to do so. The film starts out in the chaotic scene of Hussein’s botched attempt to rob a jewelry shop. This continuous four-minute scene is shot entirely from inside the store looking out through the doorway onto the bright city street. It’s a triumph of unbearable tension, where most of the violence happens offscreen but leaks into the viewer’s consciousness via the sounds of shouting and gunshots and the reaction of the crowd gathering outside. We learn what’s happening the way the larger Iranian public does: by stitching together the confusing fragments. It’s a tragedy that ends in the loss of both Hussein’s and the jeweler’s life.

The Wind Will Carry Us, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1999

The narrative then jumps back two days to show us exactly how Hussein’s seemingly ordinary existence reached this grim conclusion. For the majority of the film, we watch the subtle, desperate slippage from Hussein as a workaday citizen to an armed thief lured in by his soon-to-be brother-in-law, Ali. Panahi’s subject is the struggle of the working class, set against the hollow morality of Tehran’s elites, and in watching Crimson Gold I instantly felt at home with Hussein as he attempts to make a meaningful amount of money any way he can. I saw myself in Hussein—someone on the margins, inhabiting a body that doesn’t allow for easy hiding. Hussein’s presence is both disarming and alarming. He is a childlike figure, tender and thoughtful, who lives in hunger without hope, comfort or dignity. When, in an echo of the first violent scene, he sets foot in a jewelry shop with his fiancée, he feigns being a man of wealth. The interaction quickly ends with the shop owner humiliating him for his low social status. The shame is so overwhelming to Hussein, he’s struck with nausea and dizziness. If we choose to see Hussein through the jeweler’s eyes, he is a threat, a criminal, an oafish waste of time. If I see Hussein through the lens of my own experiences, I see an ally, a friend. I see someone making choices not very far from the ones I’ve made in the past in order to keep up hope.

I was not shocked to discover that Iranian officials banned Crimson Gold from reaching cinemas upon its release in 2003 (the film, which had a popular second life internationally, could not be considered for a Best Foreign Language nomination at the Academy Awards because it was never shown in its home country). It’s easy to see what would have upset authorities: The film depicts the hardships of working-class Iranian people, which was deemed a violation, its portrait apparently too negative and violent for public consumption. What did shock me is Panahi’s selfless, nimble direction; the ease with which he seems to work behind the camera; and his knack for finding wit and humor even amid hard truths. Early in the film, when Hussein and Ali sit in a teahouse taking an inventory of the purse that Ali has “found,” a more seasoned hustler approaches them. He offers the two youngsters some advice, enlightening them on the imperative for honesty among thieves, along with other skewed virtues. The older thief speaks with the earnestness and severity of a moral philosopher. It’s a hysterical scene, outrageous in its hypocrisy and accuracy. I saw my father in this character: a broken man in search of an audience willing to listen to a monologue designed to impart wisdom. You can almost feel Panahi smiling behind the camera as he shows us this street-smart middle-aged Iranian man—intelligent, farcical. “If you want to arrest a thief,” the man says, pointing out the corruption endemic in all strata of Iranian society, “then you’ll have to arrest the world.”

![<I>Close-Up</I>, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1990]() Close-Up, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1990

Close-Up, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1990![<I>The Wind Will Carry Us</I>, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1999]() The Wind Will Carry Us, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1999

The Wind Will Carry Us, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1999![<I>Taxi</I>, dir. Jafar Panahi, 2015]() Taxi, dir. Jafar Panahi, 2015

Taxi, dir. Jafar Panahi, 2015![<I>Close-Up</I>, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1990]() Close-Up, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1990

Close-Up, dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 1990

Censorship is nothing new to Panahi. Throughout his career, he refused to acquiesce to the demands of Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, making films that address the corruption, deceit and hypocrisy of the regime. In 2010, he was banned from filmmaking altogether (he continued anyway, and the ban made him something of a cause célèbre, with an international outcry by filmmakers and human rights agencies). He was put under house arrest and forbidden to leave the country.

I don’t always feel at home in Panahi’s films. Some of his work doesn’t have the emotional resonance of Crimson Gold, and often I feel self-conscious as a viewer—out of place, like somebody trespassing upon the lives of those who never asked to be witnessed by outsiders. But I always appreciate his risk-taking. His most recent film, 2022’s No Bears, tells the story of a couple, Bakhtiar and Zara, two Iranian exiles who are attempting to flee Turkey for a new life of freedom in France. Zara’s peril and suffering ate away at my heart days after watching it, partly because I felt complicit. Bakhtiar manages to procure a fake passport for Zara but not himself, and by the end of the film, Zara is driven to suicide and her lifeless body is discovered, washed onto the shore. At the end of the scene, you can hear Panahi shout, “Cut!”

For me, Panahi is one of the true inheritors of Iranian cinema for showing the stark class divisions and corruption within the lives of his fellow citizens. In Crimson Gold, Hussein’s decrepit home, dark and claustrophobic, is contrasted with a memorable scene toward the end of the film when he delivers a pizza to a rich man living in his parents’ massive penthouse. The man reeks of privilege. It’s impossible not to catch his expression of palpable disgust for Hussein. Nevertheless, he’s trapped in his opulence, insisting that Hussein stay and enjoy the pizza with him. The luxury triplex offers sweeping views of the city. There is an abundance of food and alcohol, and a swimming pool. Yet the man is lonely, friendless, sad. Panahi manages to turn the tables on the notion of pity, with Hussein feeling sorry for the rich man. He drinks the man’s wine and eats his food before leaving, continuing toward his fate at the jeweler’s. Even though we know the tragic ending that awaits him, we root for him anyway in his quest for a better life. Only in Panahi’s telling does this ordinary criminal finally get the dignity and compassion every man deserves.