The Color of Water

By Tiphanie Yanique

The Little Mermaid, dir. Rob Marshall, 2022

The Color of Water

Tiphanie Yanique

From Moonlight to The Little Mermaid, a wave of recent films triumphantly reestablishes the powerful connection between Blackness and the sea

December 4, 2023

In 1834 slavery was still legal on the Caribbean island of St. John in the Virgin Islands. Twelve miles across the sea from St. John, Tortola was a freeman’s land. Men and women fleeing slavery swam those 12 miles in the dark of night over the course of 14 years. In order to accomplish this dangerous escape, the swimmers needed to understand ocean currents, be knowledgeable of underwater hazards and marine predators, and have incredibly deft swimming skills. In 1848 the Danish government was forced into granting emancipation to the island. St. Johnians have remained a seafaring people, controlling many of the ferry routes in the Virgin Islands. Despite this rich aquatic history, there is a persistent stereotype that Black people in the Americas can’t swim.

From left: Moonlight, dir. Barry Jenkins, 2016; Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, dir. Ryan Coogler, 2022

Historically, film has done little to challenge this stereotype. We’ve seen Black people in movies working land, running away by land and being run off their land, but until recently we haven’t seen much of Black people in water. Disney’s summer 2023 live-action film The Little Mermaid), starring Halle Bailey, offers a years-long cumulation of a renewed vision, one where Black people reclaim their aquatic connection by embracing the metaphor of the mermaid.

The film opens with a quote from the story’s author, the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen: “But a mermaid has no tears, and therefore she suffers so much more.” The epigraph from Andersen suggests that this Disney version will tread more closely to its literary source than the plucky animated 1989 hit (also by Disney). In Andersen’s time the mer body was already representative of the social anxiety around the sexual and ethnic other. Andersen was writing in the early to mid-1800s, when Denmark—along with the rest of Europe—was being petitioned to end slavery and liberate the colonies. Andersen’s work highlights these tensions, and his little mermaid is part and parcel of his oeuvre.

The basic outline of the original story is familiar to us. The mermaid wants more out of life. She saves a prince and falls in love with him. She gives up her voice and tail to try to be with him and have a more meaningful existence. The prince falls in love with someone else. The little mermaid is pressured to kill him to save herself, but she can’t and dies of heartbreak. Perhaps you don’t know that last part, because in the Disney versions—spoiler!—she doesn’t die.

In 1847, a decade after “The Little Mermaid” is first published, the Danes conditionally end slavery. The following year, the enslaved people of the Danish West Indies launch a rebellion that frees everyone. Put into this context, we can read the recent The Little Mermaid as a key decolonial narrative, which places the body of the mermaid at the center of the battle. Importantly, the Caribbean is also the place where Columbus first saw “mermaids,” and it’s where Disney’s 2023 The Little Mermaid is set.

Avatar: The Way of Water, dir. James Cameron, 2022

The notion of water as being dangerous for capital is central to the plot of the film, set on an island where the port was once “the busiest in the region”—a claim made by many Caribbean islands at different times in their history, the Danish West Indies of Andersen included. The island leaders are anxious about their faltering economy, and the land-people blame King Triton, ruler of Atlantica (and Ariel’s father), and his merfolk for their economic struggles. It is easy to dehumanize the merfolk as monstrous others, what with their different-looking bodies and foreign customs. Pointedly, the first scene in the film is of men on a ship trying to kill a mermaid.

Yet this aquatic narrative tug-of-war between colonizer and native is not totally foreign to our cineplexes. For recent examples we need not look further than two like-minded superhero sequels from 2022, James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water and Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. Like The Little Mermaid, these films locate the control of economic power in and around water and separate the warring sides in a mythic physicality. Avatar’s Na’vi and Wakanda’s Talokanil are blue in color, and in both films the colonizer arrives because the natives have excelled at conserving their own resources (partly by building a society that is just and fair). The colonizers, whose society is desperate and depraved, have squandered their own natural resources. These outsiders want the native abundance but are strikingly uninterested in the more nuanced job of creating a world that functions well.

Given what we know of the colonizer and native encounter in the Americas, which was Cameron’s inspiration for Avatar, slavery is what is in store for the Na’vi if they give up their land, and likewise for the Talokanil before they take to the waters. The real-life Mesoamericans and Africans have the same purpose as the merpeople in The Little Mermaid: to protect their resources and their community from colonizers. In these films, water is the source of protection as well as a divide for the merpeople, a safe haven and a nearly unbridgeable point of separation.

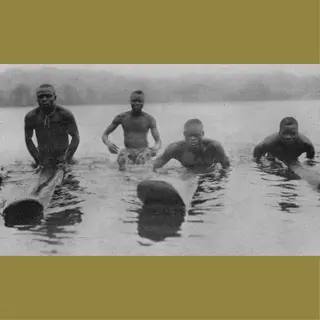

From left: Lost Wave: An African Surf Story, dirs. Sam Boyer, Sam George & Paul Taublieb, 2007; “Showing various positions on mpadua,” collection of Dr. Kevin Dawson, 1923

Interestingly, Avatar touches on that central stereotype of Black people: the idea that Black people in the Americas don’t like water and can’t swim. The film’s lead is Zoe Saldaña, an American actress of Dominican and Puerto Rican descent, who plays the warrior Neytiri. In a 2022 New York Times interview, Saldaña spoke about her intense aquatic training—including learning to hold her breath underwater for nearly five minutes—for the film, which features elaborate battle scenes in the sea. “I was scared,” she said. “I come from generations of island people, and the one thing people don’t know about island life is that if you’re from islands that have been colonized, a great percentage of people don’t know how to swim. Through folklore, you are taught to love the ocean as if it’s a goddess, but you fear it.” Saldaña is the only Black and Caribbean woman starring in the Avatar series; in referencing colonized islands in the Caribbean, she is also referencing slavery.

The reality is that Black people in the Caribbean didn’t learn to swim because they were barred by their enslavers from swimming. Knowing how to swim would have meant being able to escape, and teaching someone to swim was punishable by death. Since the mid-1960s, local white governments across the country, when forced to desegregate by the federal government, chose to fill in neighborhood pools with concrete rather than let their Black neighbors share the water. Despite the fact that the earliest known written records of surfing come from coastal Africa, it was only in 2016, with a global screen audience watching, that the American Simone Manuel became the first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal in swimming.

And yet water isn’t only symbolic of dangerous divides in film. It’s also a route. What might be the earliest big-screen images of Black people in the sea come from Julie Dash’s 1991 drama Daughters of the Dust. Importantly, this is also the first movie made by a Black woman to be distributed theatrically in the U.S. The nonlinear plot follows a Black family in 1902 on the Sea Islands off the South Carolina and Georgia coast as they prepare to migrate north. Dash understood Black people’s nuanced relationship to the ocean—that vast grave site of our ancestors. From the 1400s to the 1800s, the Atlantic Ocean was the passage for slave ships. The majority of the people sent across the water were able-bodied young adults—women of childbearing age and men young enough to work hard and sire a family. During the first half of the slave trade, these people were taken almost entirely from the coastal areas of West Africa, where they knew how to swim. Some were even captured in part because of their knowledge of boat building, navigation and sea harvesting.

Dash’s lush, poetic film emphasizes the connection between water and heritage—not only as a path for slave ships, but as an everyday portal to visit family, to find work, to see a lover, to meet clandestinely, to escape danger, to return to safety, to find peace. Daughters of the Dust continually shows characters praying, washing, dancing, posing for pictures, fighting, crying—doing the things of life—by the sea. Water is in almost every shot, even surreally under a bed, in a glass, as a talisman of protection. In the film’s ending scene, the Unborn Child narrator says, “We remained behind, growing older, wiser, stronger” as the family walks on the beach, water at their feet.

Waves, dir. Trey Edward Shults, 2019

The setting of Daughters of the Dust is the southern United States, where enslaved and formerly enslaved people navigated the waters of the Eastern Seaboard and the Gulf to move goods back and forth. In the United States, enslaved Black people manned lighthouses and rescued drowning seafarers. In my own islands, the Virgin Islands, enslaved people were needed to harvest coral, incredibly dangerous work that often required the harvester to swim out to the reefs with a sharpened cutlass, swim while cutting the coral, and then swim back to shore carrying coral. During and before the transatlantic slave trade, Black people were thought by Europeans to be unsinkable, amphibious, nymphs, tritons and, yes, mermaids.

The Academy Award–winning drama Moonlight (2016), directed by Barry Jenkins, is one of the first films in which we actually see Black people swimming, not just bathing or playing. It’s also where we first find a little Black mermaid on the big screen. The film, divided into three sections, follows the childhood and coming-of-age of a young Black man in downtown Miami. In the first section, a Caribbean man named Juan teaches the boy protagonist, Chiron, how to swim. Chiron’s name is significant here. In Greek mythology Chiron is half man, half animal. Though a centaur, his mother was a sea nymph, one of the great nymphs of the Oceanid; his grandfather was Oceanus. In Moonlight Chiron’s nickname is Little. Together his two names, little and half human, take us right to Chiron as a little mermaid. He himself is living in two worlds—with a biological mother and an adopted one. He is a queer boy trying to survive in a world that can’t accept his difference. His queerness makes him seductive to some, dangerous to others—which together make him even more mermaid.

Though he rarely smiles in Moonlight, Chiron seems to feel safe and happy with Juan in the water. As a teenager, Chiron and his friend (and possible love interest) Kevin meet on the beach. Kevin asks him: “You like the water?” Chiron says: “Feels so good,” and then, “I cry so much sometimes I feel like I’m going to just turn into drops.” This idea of turning into drops of water references Andersen’s fairy tale, in which mermaids turn into sea-foam. Fortified by the ocean breeze and the recollection that their intimacy once metaphorically transformed them into water, Chiron finds the bravery to be loved by Kevin.

“During and before the transatlantic slave trade, Black people were thought by Europeans to be unsinkable, amphibious, nymphs, tritons and, yes, mermaids.”

The 2019 drama Waves, directed by Trey Edward Shults and also set in Florida, brilliantly continues this metaphoric mermaiding. The movie, which follows a Black middle-class family’s struggles after their teenage athlete son buckles under the weight of parental expectations, inundates us with water, starting with its title. The son, Tyler, played by Kelvin Harrison Jr., has bleached blond hair smoothed into waves; the first half of the movie tells his story. During a beach scene, he and his girlfriend declare love for each other and seem to make love in the water. Tyler and his sister, Emily (Taylor Russell), each get scenes where they are submerged in water. One pivotal scene, where they embrace while crouched between the toilet and tub in their shared washroom, marks the beginning of his narrative falling apart and hers coming together. In the second half of the movie, which is devoted to the sister, Emily has what may be her first kiss in the water. The camera itself is fast, undulating. The film’s plot is based entirely on ongoing ripple effects. No major or minor point is possible without the previous ones.

The racial dynamics in Waves are important. The brother and sister are Black. The sister takes what another character calls a “leap of faith” by swimming in a lagoon surrounded by manatees. Poignantly, when Columbus wrote about seeing mermaids in the Caribbean in 1493, he was actually providing the first European record of manatees in the New World. The manatee’s scientific order is Sirenia, a Latin word that directly reveals the mammal’s siren mermaidness. In this scene, the sister swims as a mermaid.

From left: Daughters of the Dust, dir. Julie Dash, 1991; Avatar: The Way of Water, dir. James Cameron, 2022

In Disney’s live-action The Little Mermaid, we finally see a direct engagement with the long and meaningful history of the aquatic life of Caribbean and other colonized people in the Americas. But now the Black mermaid is more than a mere metaphor.

I saw The Little Mermaid on the big screen at a special showing in Atlanta this past spring, on the day before its official release. Walking into the theater with me were pairs of sharply dressed adult Black men, trios of women in cocktail dresses sipping drinks, groups of fashionable young adults of various genders with bushels of popcorn tucked under their arms and bags of candy dangling from their fingers. This was an event, a party, a fancy date night. Most of these people did not have children with them. Most were, like me, children themselves when Disney’s animated version came out.

Though I am a mother, I’d left my own children at home. A woman sat down next to me, parking a baby stroller in the aisle. During the previews she turned and said, “My daughter is sleeping, but I have to use the bathroom. I’ll be right back.” She didn’t even ask me; she just assumed. I exchanged an alarmed glance with the woman on my other side. When the mother left, I peered into the pram to make sure there really was a baby in there. There was.

The current The Little Mermaid places a strong emphasis on familial connections and misconnections. The movie’s dramatic impetus is indeed a family affair. Ursula and King Triton are siblings. King Triton is the favored older brother; his sister, Ursula, has been relegated to the caves, taunted as the sea witch. She’s resentful, and it doesn’t seem entirely unwarranted. Ursula’s manipulation of her niece, the little mermaid Ariel, is in part a defensive response to the adoration shown to her brother. This drama is also a reflection of Andersen’s original. In his story, watching her own sisters experience the above world fuels the little mermaid’s longing for it. But later, to save the little mermaid from death when her quest to marry the prince fails, her sisters offer their hair as payment to the witch for a knife. The little mermaid must use the knife to kill the prince and break the witch’s spell. We can note that in Andersen’s fairy tale, Triton does little to support his daughter in her hopes for autonomy and nothing to help save her life.

From left: ocean views in Waves and The Little Mermaid

In Disney’s new live-action version, Ariel leaves the fairy-tale version behind—she not only gives us the original Andersen story but also transcends it: The last time we see the image of the little mermaid in the film, it’s the jade figurine of a mermaid that Prince Eric has given to her. Notably, while Disney’s 1989 animated version ignored or skirted much of the horror of the author’s tale of women and girls being punished for wanting more out of life, 2023’s Ariel is punished—but in the end she physically fights Ursula to reclaim her voice and then flings the token mermaid figurine into the sea. Ariel winds up now magnanimous, allowing her father the opportunity to apologize and become part of her happy ending.

As the credits rolled, the mother of the toddler turned to me and said, “I think she did a great job.” I thought she meant her daughter’s behavior during the movie, so I nodded at the stroller and smiled. “I mean Halle,” the woman said. At first I found this strange. Why wouldn’t the lead actor have done a great job? But then I remembered all the hullabaloo that Ariel should have been cast as a white actor. After the lights came up, a group of white men who were sitting in the row in front of me were exclaiming to each other. “Halle was perfect,” one said, “she carried the movie.” “This was a dream come true,” said another. They were speaking to each other. But they were really speaking to everyone who had been doubting that a girl from the Caribbean, a Black girl, a girl of colonized people, could be a mermaid.