Sean Bobbitt: The Constant

By Yonca Talu

Hunger, dir. Steve McQueen, 2008

The Constant

Cinematographer Sean Bobbitt’s unlikely two-decade partnership with Steve McQueen is a sublime alliance of practice and concept

By Yonca Talu

February 2, 2024

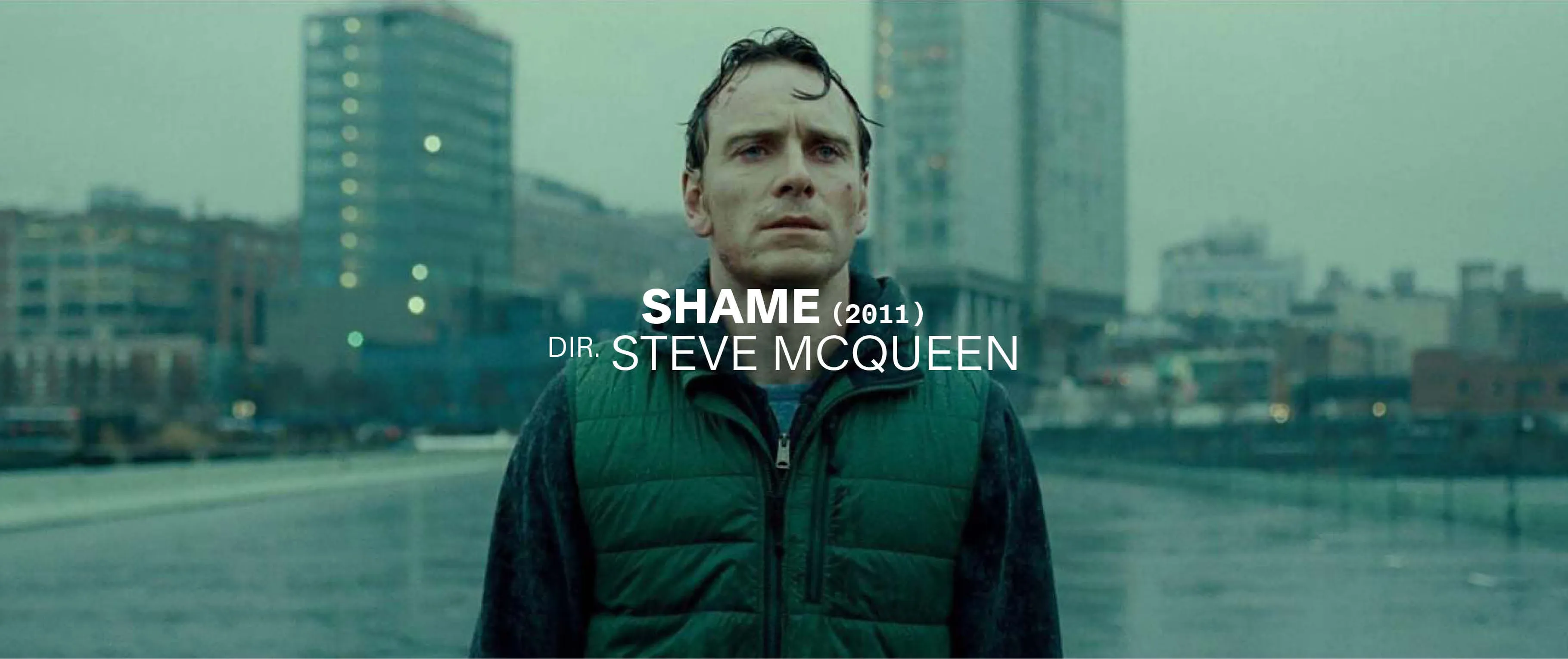

On the cusp of the new millennium, Sean Bobbitt was at a turning point. After years of toeing the line as a TV news and documentary cameraman, he had just shot his first narrative feature, which caught the eye of the Turner Prize–winning visual artist Steve McQueen. Teaming up despite their radically different professional backgrounds, the two men have gone on to create some of the most formally daring and hard-hitting works of contemporary cinema, from the historical dramas Hunger (2008) and 12 Years a Slave (2013) to the modern-day fictions Shame (2011) and Widows (2018). Using visual economy, long takes and arresting compositions, McQueen and Bobbitt plumb the depths of human suffering—as much self-inflicted as caused by others—and highlight the dignity and resilience of their characters in traumatic circumstances. Galerie spoke with the Academy Award–nominated, American-born British cinematographer about his creative partnership with McQueen and his process of bringing the filmmaker’s politically charged tales to the screen.

Sean Bobbitt (left) and Steve McQueen on the set of 12 Years a Slave

You first started collaborating with Steve McQueen on his film installations. As someone with a background in shooting TV news and documentaries, what was it like for you to step into the art world?

It was a totally improbable experience. Coming from TV news and documentaries, the art world was about as far away as I could get. The storytelling I was used to doing was very literal, on point and compressed. But when I met Steve McQueen, I was at a time of transition. I had recently moved into the fiction film world with Michael Winterbottom’s Wonderland [1999], which I’d found to be an incredibly liberating step. Apparently Steve and his wife, Bianca [Stigter], watched Wonderland together, and she said to him, ‘‘This is the cinematographer you should be working with.’’ So he tracked me down and invited me for a cup of tea to talk.

What did you talk about?

Steve did most of the talking while I just sat there and smiled and nodded. [Laughs] I kind of knew what an art installation was, but I’d never seen any of Steve’s work. So I had no idea what he was talking about. But I thought, I like this guy—he has a passion that I want to follow. The first thing I shot with Steve was his installation Western Deep [2002], down one of the deepest gold mines in the world [i.e., the now-closed TauTona mine in South Africa]. He gave me all sorts of things to read about the history of Africa and mining. We also had long chats about the relationship between mining and slavery. He was helping me prepare, I think, in the full knowledge that I was completely unprepared for what was going to happen. [Laughs] It took us two hours or so to get from the top to the bottom of the gold mine. When we arrived, I was like, ‘‘Okay, we’re here. What do we do now?’’ And Steve said, ‘‘Well, there’s something here. We have to find it.’’

And how did you react to such a casual-sounding statement?

My initial response was anger. I was like, Oh God, he’s taken us to one of the most dangerous places in the world, and we don’t even know why we’re here. But then I thought, Wait a minute—we’re here for a reason. So I started looking around, and within literally two minutes, a feeling of euphoria came over me. For the first time in my life, I was hunting for and creating images for their own sake, without being bound by a narrative. It was wonderful to suddenly have that freedom after almost 20 years of working in the very constrained space of news and documentaries, where you’re usually not rewarded for using your imagination. You arrive somewhere and you’re told, ‘‘We’re looking for this, this and this.’’ But with Steve it was the opposite.

The conversation sequence between Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) and Father Dominic Moran (Liam Cunningham) in Hunger

How much did Steve McQueen’s installation work inform his first feature, Hunger?

Hunger was very informed by one of Steve’s installations, 7th Nov. [2001], which left a mark on me and a realization on him. It’s a shot of the back of a man’s head projected in a small room with a bench. It goes on for about 20 minutes, and it’s accompanied by a male voice telling a story in the first person. Over time you realize that the man speaking has accidentally shot his brother and that he’s actually Steve’s cousin. As you sit there, you have no sensory input apart from the image and the voice-over. And the more you sit there, the more you feel as if the camera were zooming in on the man onscreen. Suddenly you also realize that across the back of the man’s shaved skull is an enormous scar, and you think, Was that there at the beginning, and what does it mean? Since you’re not allowed to leave the image, you start to project your own ideas into it, and it becomes inextricably linked with the story told in voice-over in a way you don’t understand.

I think what Steve learned from this installation is the power of holding a shot. If you don’t put an edit in, the audience is not reminded that they’re watching a film. They’re just held by whatever’s happening in the frame, and the longer it goes on, the more they get drawn in and drawn in and drawn in. It’s like a multiplier for emotion—a very personal emotion that the viewer generates and projects onto the screen.

That resonates especially with Hunger’s 17-minute continuous wide shot of IRA prisoner Bobby Sands’s conversation with a Catholic priest.

Yes. As we were talking about how we were going to shoot that scene, Steve said, ‘‘Look, when I come into a room where two people are having a conversation, I sit down and listen to them. I don’t walk around the room to look at them from different angles and get closer or farther away from them.’’ The simple honesty of this statement meant that there was no other way to shoot Bobby Sands’s conversation with the priest but in a continuous wide shot. Everyone swears there’s a subtle zoom-in in that shot, but there’s nothing but two very fine actors [Michael Fassbender and Liam Cunningham] acting very finely.

While shooting Hunger, did you draw at all on your experience covering the Troubles?

Not really. When I worked in Belfast as a news soundman in the ’80s, I thought I knew what was going on, but I didn’t. All the information coming out of the H-Blocks [i.e., the Maze prison in Northern Ireland] was controlled by the British government. And all the dispatches put out by the IRA about the conditions in the H-Blocks and the treatment of prisoners were dismissed as propaganda. The press followed this narrative, and as a member of the press, I absolutely did as well. We knew no better. So it was a shock to discover the reality when Steve brought me on Hunger. His research was phenomenal. He did a huge number of interviews with survivors of the H-Block ‘‘blanket’’ and ‘‘dirty’’ protests and hunger strikes. We also visited the actual H-Block, the cells and the hospital room where Bobby Sands died. At one point it even looked like we were going to be able to shoot there, but that fell through for political reasons. Luckily our production designer, Tom McCullagh, had experience building replicas of the H-Blocks. He’d even stored away the steel cell doors he’d built for another production, so he reused them on Hunger.

From left: Shame, dir. Steve McQueen, 2011; Widows, dir. Steve McQueen, 2018

What was your approach to filming Hunger’s claustrophobic cell scenes?

The cells in Hunger, which were re-created in a warehouse outside Belfast, are exactly the same size and shape as the real H-Block cells. What we shot was what we could shoot in those exact cells. The idea was that as the audience, you’re there. This is the reality. There are no tricks, no cutaway shots. The only time we filmed cutaways from outside the cells was for safety, in the scene in which Bobby Sands and his fellow inmates go crazy and break up their cells.

Did you and Steve McQueen take inspiration from any religious paintings to portray Bobby Sands’s physical deterioration? There are shots of him lying in his hospital bed during his hunger strike that evoke Andrea Mantegna’s 15th-century painting Lamentation over the Dead Christ.

We didn’t look at that painting, but we did look at Diego Velázquez’s [17th-century] religious paintings. Steve gave me several art books on Velázquez. But we didn’t conceive those scenes in Hunger as an homage to or a re-creation of Velázquez’s work. We were just inspired by his compositions, which are very symmetrical and balanced, with the Christ figure in the middle and vectors moving away from him.

As a cinematographer, how did you go about capturing Michael Fassbender’s self-sacrificing performance as Bobby Sands?

My job as a cinematographer is to respect the actors and create a safe space in which they can be vulnerable and do their best work. In Hunger, Michael Fassbender’s performance is remarkable not only for its intensity and truth but also for what he did to his body [i.e., losing more than 35 pounds for the role]. When you’re working with an actor of such integrity and skill, it’s a privilege to be in the room with them, behind the camera, and be the first eye that their performance goes through. So you have to try to be faithful to their work through the composition and lighting. I don’t light everything up and then take it down. I try to light the set exactly as it should be, within the emotion of the scene, and in a way that allows the actors to go wherever they want.

Is that also how you lit Steve McQueen’s second feature, Shame, which stars Michael Fassbender and Carey Mulligan?

Yeah. On Shame, Michael and Carey [playing estranged siblings] were acting out serious, raw emotions that they were pulling out of their own lives. I had to give them the space and time to do that without trying to impose on them ideas like ‘‘Your light is here’’ or ‘‘You have to stop here.’’

The initial scenes of Shame, which chart Brandon’s routine as a sex addict, are filmed in a cold and detached style. But after his sister, Sissy, forces her way back into his life, the film takes on a more rough, immediate quality, with a lot of handheld shots that convey Brandon’s gradual loss of control.

Yes. It seemed like a natural visual progression to establish Brandon as someone in control and then mirror his slow self-destruction with the camerawork. At the beginning everything is the way he wants it and he does what he wants. There’s nothing that weighs him down, no frippery in his apartment. We wanted to show that through very solid, composed frames with strong vertical lines running through them.

The film opens with a striking overhead shot of Brandon lying awake in his blue-sheeted bed, his hand resting on his navel and his body positioned toward the edge of the frame. Did Steve McQueen already have that angle and composition in mind, or were they chosen on set?

He already had the angle in mind. But the composition just sort of happened because that’s the way Michael lay down in bed, and it felt right to have him positioned toward the edge of the frame. There’s something discordant and awkward about that shot. It subliminally sets up Brandon as an unstable character. It’s one of those shots you can read a lot into, but it also just has a very interesting composition.

Another early shot in Shame with a very interesting composition is the static long take of Brandon walking around naked in his apartment, which is framed from an angle that allows us to see into both his bedroom and living room. How did you come up with that camera position?

One of the great aspects of my collaboration with Steve is that he brings me in very early in preproduction, so I get to spend a lot of time on the locations. On Shame, I spent a lot of time in Brandon’s apartment looking for compositions with a still camera. Then I went through those stills, graded them and showed them to Steve, which sparked ideas. We don’t do storyboards or shot lists and don’t formalize anything until the day of the shoot, when we bring in the actors. But for the shots in Brandon’s apartment, like the one you mentioned, I knew exactly what the angle should be and was able to precisely set the camera because of all the time I had on that location.

“For the first time in my life, I was hunting for and creating images for their own sake, without being bound by a narrative.”

Viola Davis in Widows

What was the process of finding Brandon’s apartment, which is such a prime location in the film?

Our overriding theme was that people like Brandon in New York live and work in the sky, high up in buildings, and come down to earth at night to go out and hunt, as it were. But it took us forever to find a high-rise apartment with the right orientation—north-facing with no direct sunlight. We also wanted the apartment to have very New York elements, but not in a touristy way. If you look closely in the film, you can see the Empire State Building out Brandon’s window. Although no one notices it, it means something, and it meant something to us as we were making the film.

The film does treat New York as a character of its own.

Yeah, it’s a New York story. Steve went to film school in New York for a while [i.e., NYU Tisch School of the Arts, 1993–94] and knows the city quite well. So it was very important to him that New Yorkers who see Shame recognize the city as their own. We didn’t want to make a classic New York movie where the cab goes by and you see the Statue of Liberty in the background. We wanted to be true to the city and capture what’s really there: the green awnings on the street and the colors of the night.

How did you shoot the subway sequences?

We were a very small crew and light on our feet. We just hopped on the subway at two in the morning and shot some of those sequences. I mean, we were jumping from train to train to train to avoid getting caught. People call it guerrilla filmmaking, but I hate when they say that. It’s desperate filmmaking!

It’s difficult to imagine that those scenes were filmed so spontaneously, particularly the one in which Brandon seduces a young woman sitting across from him on the train.

That was a scene on which we had control. The lady who oversaw film shoots on the subway loved Steve. So we got away with a lot more than most people would ever do, which was great. But it was a very complex process to film the Steadicam shot of Brandon following the young woman out of the train and up the platform stairs, then losing her in the crowd. There were so many things that could go wrong, and we only had three takes because of time constraints. But our genius Steadicam operator, Dave Chameides, absolutely nailed it. He was able to fight the inertia of the train stopping and the crowd going up the stairs while also holding a specific frame so that Brandon could lose the young woman at exactly the right time and place. It’s one of my favorite Steadicam shots of all time. I actually watched it again today because it just makes me feel good. [Laughs]

Speaking of filming in New York, I wanted to ask about your American roots. You were born in Texas to American parents, right?

Yes. I was born in Corpus Christi, Texas, and grew up there until I was six.

What did it feel like to shoot Steve McQueen’s third feature, 12 Years a Slave, in the American South, in Louisiana, and immerse yourself in your native country’s traumatic history?

It felt fascinating and horrifying in equal measure. On a personal level, I had no idea that my grandparents came from Louisiana. My father was actually born there, in a city called Plain Dealing. He and my mother visited me during the shoot of 12 Years a Slave, and we drove to all the places in Louisiana where he lived as a child. It was a period in his life that I didn’t know about, in the same way that slavery was a period in American history that I’d only read about. I think in America, slavery is kind of brushed under the rug. Solomon Northup’s [1853] memoir, Twelve Years a Slave, used to be compulsory reading for American students, but it was slowly dropped off the reading list. So that knowledge disappeared from white education and was replaced by false narratives coating the true horror: the degradation, exploitation and murder involved in slavery. It’s immoral to think that you can forget about it. You can’t. That’s why it was very important to us to bring Solomon Northup’s story to a wider, specifically white audience and say, ‘‘Look, this is what happened. There were no benevolent plantation owners who took care of their happy slaves.’’

You’ve said that your visual approach to 12 Years a Slave was influenced by Jim Jarmusch’s collaborations with the late Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller, who also shot Steve McQueen’s 2002 installation Caribs’ Leap.

Yes. Steve was very good friends with Robby Müller and lived near him in Amsterdam. I was also very fortunate to meet and spend some time with him. What a lovely man he was! He’s one of my heroes, and his influence is forever lasting on everything I do. One of the main elements of that influence is something that’s also deeply rooted in Steve’s soul: simplicity. Find the right frame and hold it. It’s very straightforward: This is what needs to be told, and this is the frame that tells it. Whether it’s through a symmetry that gives people comfort or an asymmetry that puts them on edge, your frame should encapsulate the emotion of the scene. That’s what Robby Müller was a genius at and never showy about.

From left: Chiwetel Ejiofor in 12 Years a Slave; Viola Davis in Widows

Tell me about finding the frames that compose Solomon’s near-hanging sequence in 12 Years a Slave, which was filmed at the historic Magnolia Plantation in Louisiana.

We spent a lot of time thinking about that sequence. We visited many plantations in Louisiana to find a tree with a limb that you could hang someone off of. We also wanted the tree to be in proximity to the plantation house and the slave shacks, which was the case at the Magnolia Plantation. By having everything close together, we were able to show that life goes on around Solomon as he’s hanging from that tree. The slaves in the background have no choice but to continue their work, while the plantation’s overseer and mistress watch from the porch and balcony of the house. This is just everyday life for them.

There’s also that shot of the children playing cheerfully behind Solomon as he chokes, the juxtaposition of which makes the scene even more unbearable.

Yes. His life is worth nothing and as such has already been dismissed. All of that is conveyed without any words or dialogue, which is so much more powerful.

Your latest collaboration with Steve McQueen, the Chicago-set Widows, is his most dialogue-driven film and first conventional genre piece. Did you two tackle it any differently than his previous work?

No, not really. You know, the [heist] thriller genre is something that’s of interest to every filmmaker. We had a bit more money, and we had action and fight sequences. So we actually did a couple of storyboards, which we’d never done before. But our main motivation was to bring back to life Steve’s childhood memory of watching the original Widows, which was a groundbreaking ’80s British TV series with an all-female leading cast. That aspect of the show has always been important to Steve, who’s very close to his mother and sister, and was part of the reason why he wanted to adapt it into a film.

A moment that visually stands out in the film is the unbroken car ride that takes us from a poor to a wealthy neighborhood of Chicago in a matter of seconds.

That’s the way Chicago is. I once shot a documentary about drugs there, and I couldn’t get away from the fact that there was such incredible poverty and wealth on either side of the same road. I’ve never seen anything quite like that elsewhere in America, let alone in the world. Does the proximity of poor people to wealth mean that any of it might rub off on them? Quite the opposite—it’s always there, in their faces, but they will never actually obtain it. It was very important to us to try and show that in Widows.

That shot in Widows is also very bold because of your and Steve McQueen’s decision to place the camera outside the car and have the conversation between Colin Farrell’s politician character and his campaign manager (Molly Kunz) play out in voice-over.

Yeah. I don’t remember the exact genesis of that shot, but it just felt right as I was pitching it to Steve. It was the sort of shot that he would embrace and a lot of directors wouldn’t. It’s a joy to be encouraged to find shots like that, shots that aren’t conventional but have a real meaning to them. Ever since our first collaboration, Western Deep, Steve has opened me up to the freedom to look for such images, and I’m forever grateful to him for that. It’s allowed me to progress, as a cinematographer, in a completely unique and different direction from the one I was heading in.