Lol Crawley: The Environmentalist

By Phil de Semlyen

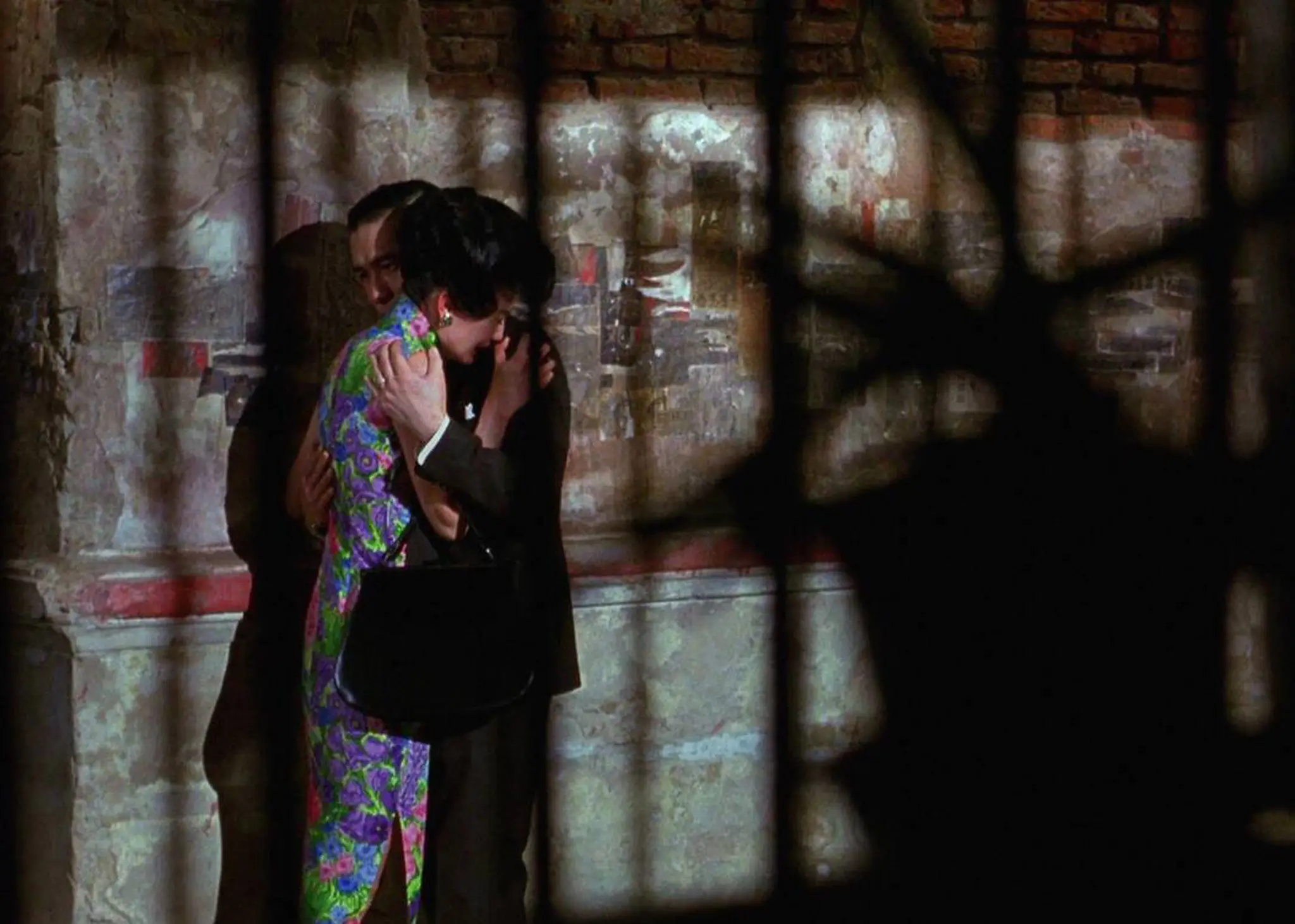

Ballast, dir. Lance Hammer, 2008

The Environmentalist

From Ballast to White Noise, cinematographer Lol Crawley’s brooding landscapes tap a potent emotional register

By Phil de Semlyen

September 15, 2023

“I do a good line in stark,” says Lol Crawley, whose masterly frames are noted for their haunting, saturnine compositions. The lugubrious aesthetic is perfectly suited to carefully picked projects that speak to the zeitgeist—populism in the age of Trump, fame in Instagram era, consumerism run amok—in left-field ways. Working with Noah Baumbach on White Noise (2022), the acclaimed cinematographer brought a note of realism to an absurdist satire on materialism and mass media. Before that came a pair of Brady Corbet films, the painterly The Childhood of a Leader (2015) and splashy pop opus Vox Lux (2018), which saw Crawley’s subdued lighting of 1919 parlors and contemporary hotel suites imbuing explorations of populism and our obsessional relationship with fame with quiet grandeur (a third Corbet collaboration, the historical drama The Brutalist, is in postproduction).

From left: 45 Years, dir. Andrew Haigh, 2015; Christina’s World, Andrew Wyeth, 1948

As an inquisitive kid, Crawley remembers rolling his hand into a makeshift viewfinder and peering through car windows on journeys near his home in leafy Shropshire, England, on the Welsh border. “There may have been something in that attempt to frame the world,” he notes of these early forays into composition. Crawley’s arresting use of landscape to communicate the inner lives of characters, in films as varied as Andrew Haigh’s poignant marriage drama 45 Years (2015) and Marc Munden’s vivid adaptation of The Secret Garden (2020), is a recurring theme in his work.

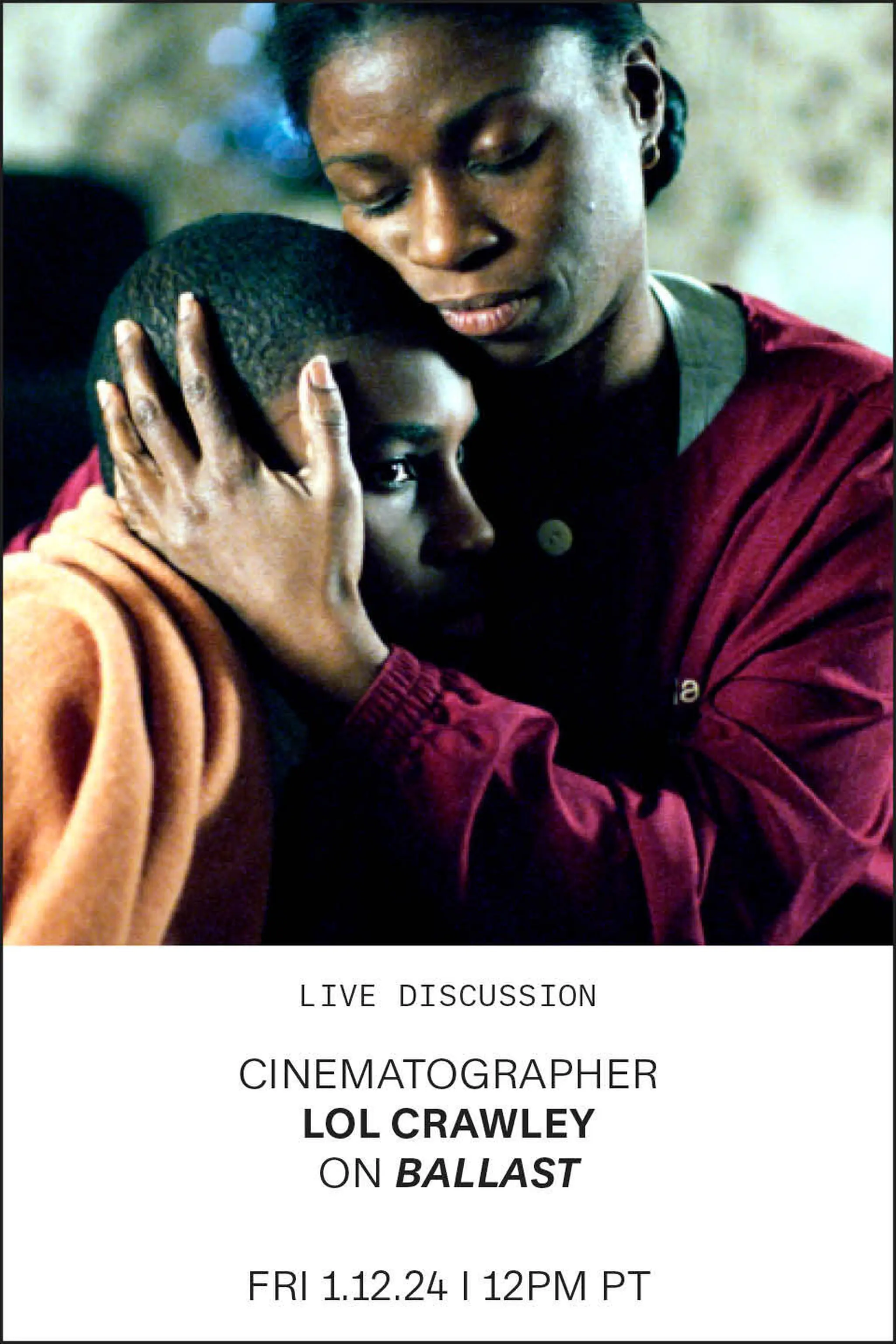

There were hints of what was to come early in Crawley’s career, amid the wintry stubble of the Mississippi Delta boondocks where he shot Ballast (2008) for Lance Hammer. An aching, tight-knit tale of three African-American family members coping with grief and animosity, it follows a taciturn store owner (Micheal J. Smith Sr.) struggling to come to terms with his brother’s suicide while parrying the hostility of his nephew (JimMyron Ross) and sister-in-law (Tarra Riggs). Using non-actors and filmed on grainy 35mm with available light in gloomy interior spaces or backdropped by the wintry cotton fields of the Deep South, Ballast won Crawley a Sundance award and scored him an admiring email from legendary cinematographer Harris Savides (Milk, Birth). It also got the attention of Hollywood, and he still gets hired on the back of it.

White Noise, dir. Noah Baumbach, 2022

Filmmakers often talk about capturing something in their first film that they always strive to repeat. Does that apply to cinematographers too? Are there happy accidents?

A friend likes to tell me that I’ve never bettered my work on Ballast, that it was my Astral Weeks. [Laughs] I’m incredibly proud that it has a real place in American independent cinema. But you’re right, there were happy accidents—things that I didn’t know or hadn’t experienced. It was filmed using a lot of available light and very caught focus, so it had a very specific feel, and I often thought I was screwing up. I was young and Lance pushed me. I’d put lights up, go away, come back, and he’d have taken them down. I’d think, Okay, I’ll shoot with available light, but I’ll still have a truckload of lights [as backup], and he’d say, “No, if we’re doing this, this is how it should look.” He got me there on the premise of shooting with available light and with non-actors. We were really bold. I remember turning to Lance and saying, “I’m not going back to the U.K. until this is done.” Whatever it took, I was in it. It’s rare that you feel that way.

In films like The Help, Mississippi Burning and The Long, Hot Summer, Mississippi is usually a rich, saturated environment. Ballast isn’t that at all.

The very first image that Lance showed me [in preproduction] was a ghostly shot of these skeletal cypress trees in the swamps of Mississippi, and I was just blown away by it. I’d made a short film called Love Me or Leave Me Alone (2003) for Duane Hopkins, which was shot with available light and anamorphic [lenses], which you’re told not to do. People loved it, and it was that film, and the films of the Dardenne brothers and Breaking the Waves, that inspired Lance. He wanted this overcast European aesthetic, so we shot in the wintertime and we’d refuse to shoot when it was sunny. But given that the film is about grief and reconciliation, it just felt so appropriate that the landscape melds with the tone of the characters.

The opening shot—of 12-year-old James standing alone in a field—is stunning. How did it come together?

Lance’s screenplay had JimMyron Ross’s character in a field with these geese. But every time we tried to film them, they’d fly away. So we had just a few of us in this one vehicle—the sound recordist, me, the camera assistant, JimMyron and Lance—and we'd sneak around the Delta creeping up on geese. We’d see them in the distance, set ourselves up, walk into the field, and as they’d start to fly away, we’d just run toward them. We didn’t even intend to use this shot. I love it when things you think shouldn’t go in find their perfect place.

“I like the unsettling quality that comes from an unmotivated light source.”

It’s that happy-accident thing again.

You have to be open to stuff. I love [In the Mood for Love cinematographer] Christopher Doyle, as much for his spirit as his photography, and he’d say: “In the West you say, ‘Here’s the frame, how do you fill it?’ In Asian cinema you say, ‘Here’s the world, how do I frame it?’” If I’m looking at the blueprints, I’m missing something.

What was your visual philosophy on Ballast?

I wanted the image to feel less technically precise. On Ballast we were underexposing the film and leaving it longer in the chemicals to distress it. With modern stocks and modern lenses it’s almost too good, and I want to feel the film and the emotion of it as well. You could be as base as to say that the grittiness of the character is reflected in the grittiness of the film, but essentially I want the film to feel more impressionistic, to feel more like a painting than a photograph. It’s tough to articulate—like arguing vinyl versus digital—but you’re making choices that just feel correct, and maybe that’s enough.

From left: JimMyron Ross and Micheal J. Smith Sr. in Ballast; Natalie Portman and Raffey Cassidy in Vox Lux, dir. Brady Corbet, 2018

You mentioned Breaking the Waves as an influence. What do you think the aesthetic legacy of the Dogme 95 movement has been?

It took elitism out of filmmaking, and anything that’s a little punk is really important. The one thing that inspired me about [Festen cinematographer] Anthony Dod Mantle, another favorite of mine, is that he shoots on whatever format serves the film and makes it look incredible. The danger now is that we’re using digital cameras that are trying to emulate 35mm, so our palette has been restricted. We have a tendency to be a little safe. Festen was unapologetic and [the style] served the medium, so why the heck not? I hope that philosophy, along with the aesthetic, keeps inspiring future filmmakers.

Is there a landscape painter who has inspired you in your career? I understand American painter Andrew Wyeth was a touchpoint for your work on Hyde Park on Hudson.

‘[Wyeth’s] Christina’s World was a reference, but I’d underestimated the strange uncanniness of his paintings at the time. I like the unsettling quality that comes from an unmotivated light source. You’ll see the people in the landscape, and the light falling on them seems to come from a different place. That’s something I've tried to embrace and emulate in my films.

What is it about the American landscape that inspires you?

I was always really taken with the iconography of America. As a kid, I watched this Channel 4 series called Road Dreams, which was a series of Super 8 films across America, set to music. I loved Paris, Texas and imagined that the way I felt about America was the way Wim Wenders or Ang Lee might have felt about it: someone from outside seeing something in the landscape that a local wouldn’t see. For the same reason, I’d struggle making a movie in London about kids on a housing estate. You need to bring the excitement of seeing something for the first time.

You grew up in Shropshire, England, and have talked about being inspired by the landscapes of your childhood. Can you feel that in your work and your choices?

Yeah, I think so. I remember being a kid and being very unsettled in the evening times. Night and day were fine, but the strange hinterland as the sun was going down made me feel very melancholic. There’s definitely something there that I come back to—maybe it’s the lack of direct light and that softer pastel palette that feels slightly aching and brooding, and maybe Ballast is an example of that. When you asked if we knew we were making something important with Ballast, I think I knew that we were catching that.

From left: Road Dreams, dir. Elliott Bristow, 1980; Breaking the Waves, dir. Lars von Trier, 1996; Paris, Texas, dir. Wim Wenders, 1984; In the Mood for Love, dir. Wong Kar-wai, 2000

Landscapes have been a throughline in your work, from 45 Years to The Secret Garden. The film you shot in Alaska, On the Ice, features isolated figures backdropped by a very stark landscape.

Landscapes are an opportunity to celebrate that same aching, brooding mood. I also shot a film in Armenia for Braden King called Here, and so much of that was about landscape. It’s about time and place and relationships, and Ben Foster’s character was a cartographer, so yeah, every box ticked. I definitely gravitate to those stories and emotions. I’d love to shoot a movie set in space.

What draws you to a film set in space from a visual perspective?

It’s a landscape, but there’s nothing there. The study of something incredibly small in the vastness of this environment. An intelligent, adult-themed space movie like Arrival would be a big draw.

How would you conquer the available light issue?

Just turn on all the big lights in the spaceship. [Laughs]