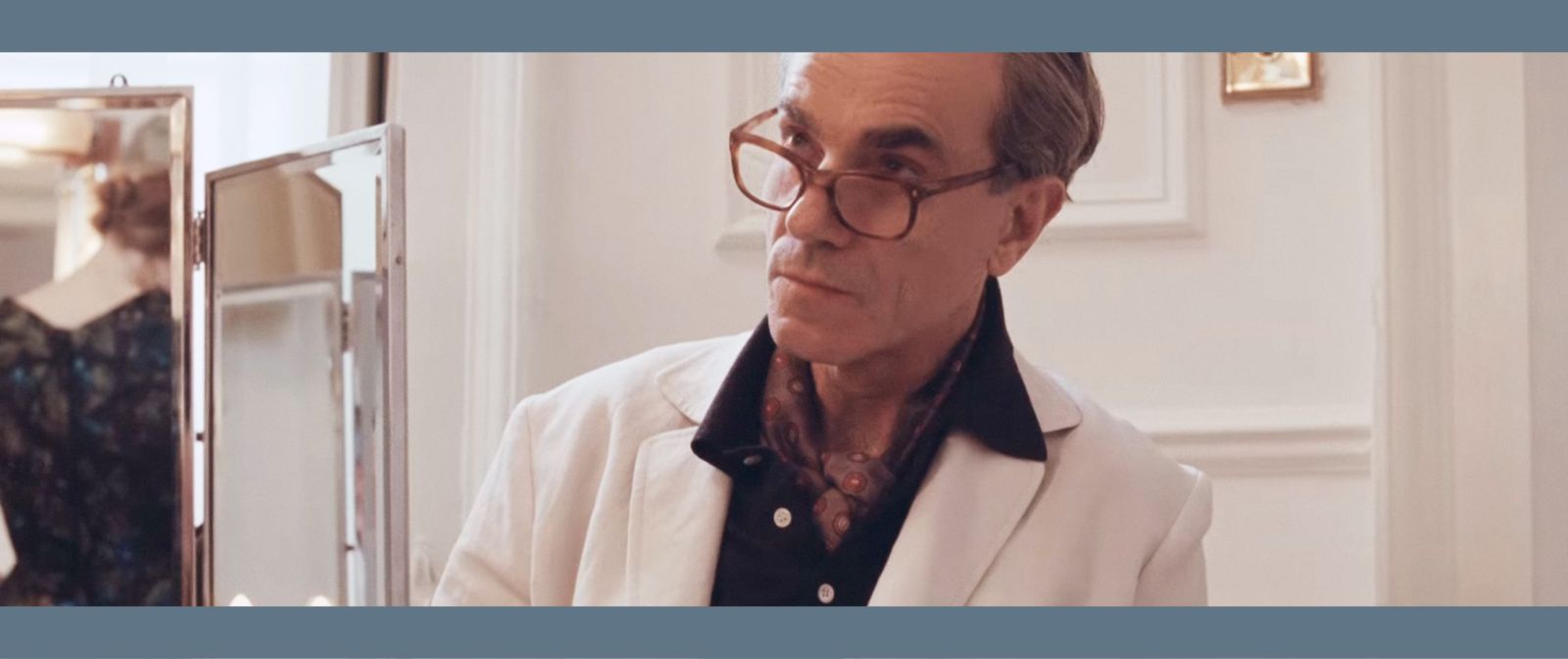

The Historian: Mark Bridges

Phantom Thread, dir. Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017

The Historian: Mark Bridges

BY MARIELLE HUEY

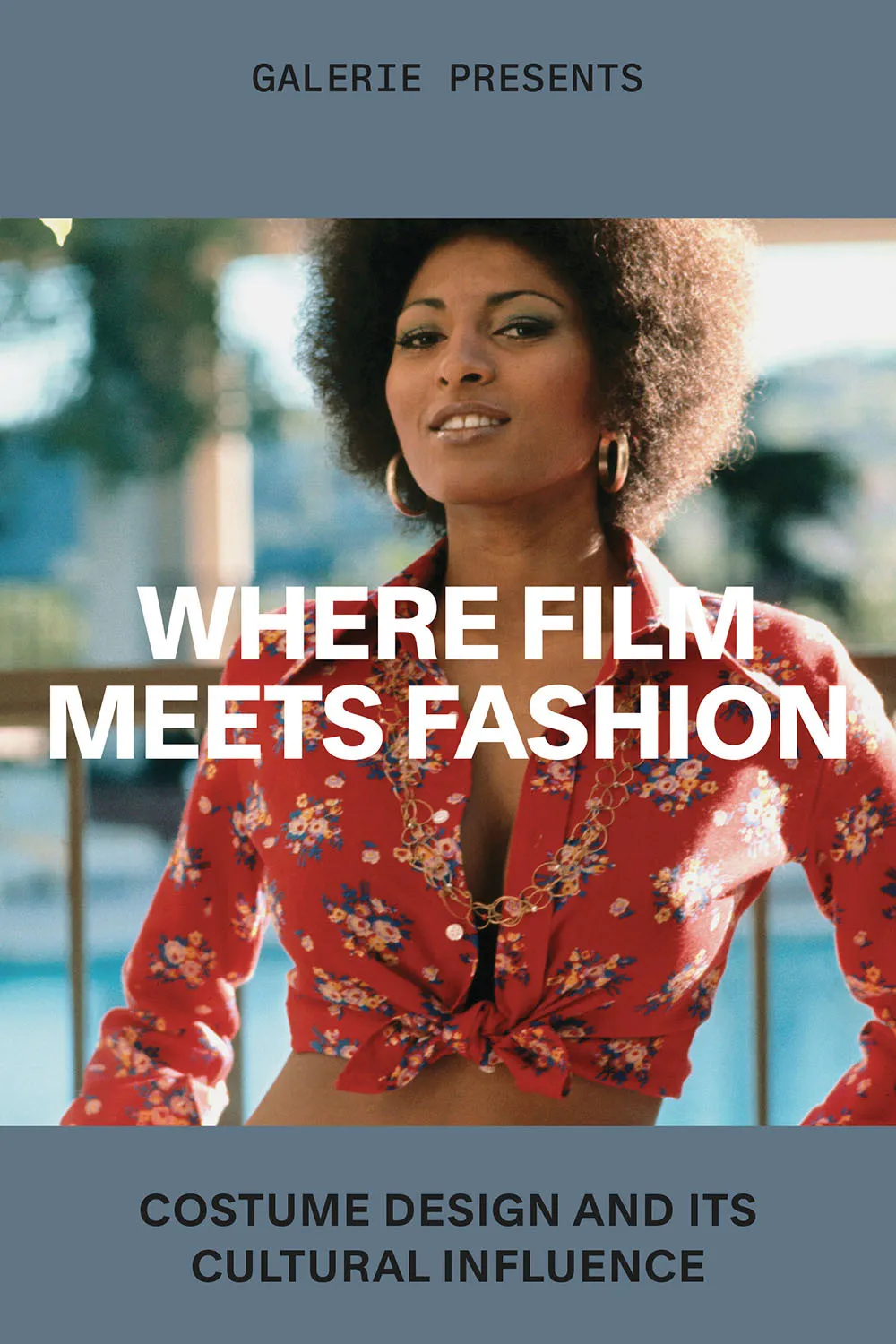

Paul Thomas Anderson’s costume designer on finding real and phantom threads between the past and the present

October 1, 2024

“The challenge to make it seem real, that’s what I look for in a script,” explains veteran costumer Mark Bridges. “But also the first 20 pages—if you lose me there, it’s a no-go.” Among the projects that have made the cut over Bridges’s three-decade career: Maestro, The Fabelmans, Silver Linings Playbook and every Paul Thomas Anderson movie since Hard Eight. Bridges’s lifelong immersion in the interplay between clothes and storytelling emerged as a viable career path after college, when the Niagara Falls native began working as an assistant to the legendary Broadway costumer Barbara Matera. Since being poached by Hollywood, his research-heavy, detail-oriented work for Anderson and other A-list directors has netted two Oscars (for The Artist and Phantom Thread) and cemented Bridges’s reputation for conjuring evocative, period-accurate re-creations of bygone eras, from 1950s London to 1970s San Fernando Valley. Bridges met up with Galerie for a video interview at Palace Costume in West Hollywood to talk personal history, preproduction process and the art of time traveling through clothes.

![]()

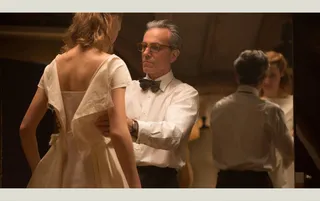

Paul Thomas Anderson and Mark Bridges at the Chateau Marmont in 2018

![]()

Daniel Day-Lewis in Phantom Thread

What drew you into the costume world?

This job is a combination of everything that I love—history, fabric, clothes, color. Looking back, it seems like a natural choice for me. I always loved Halloween.

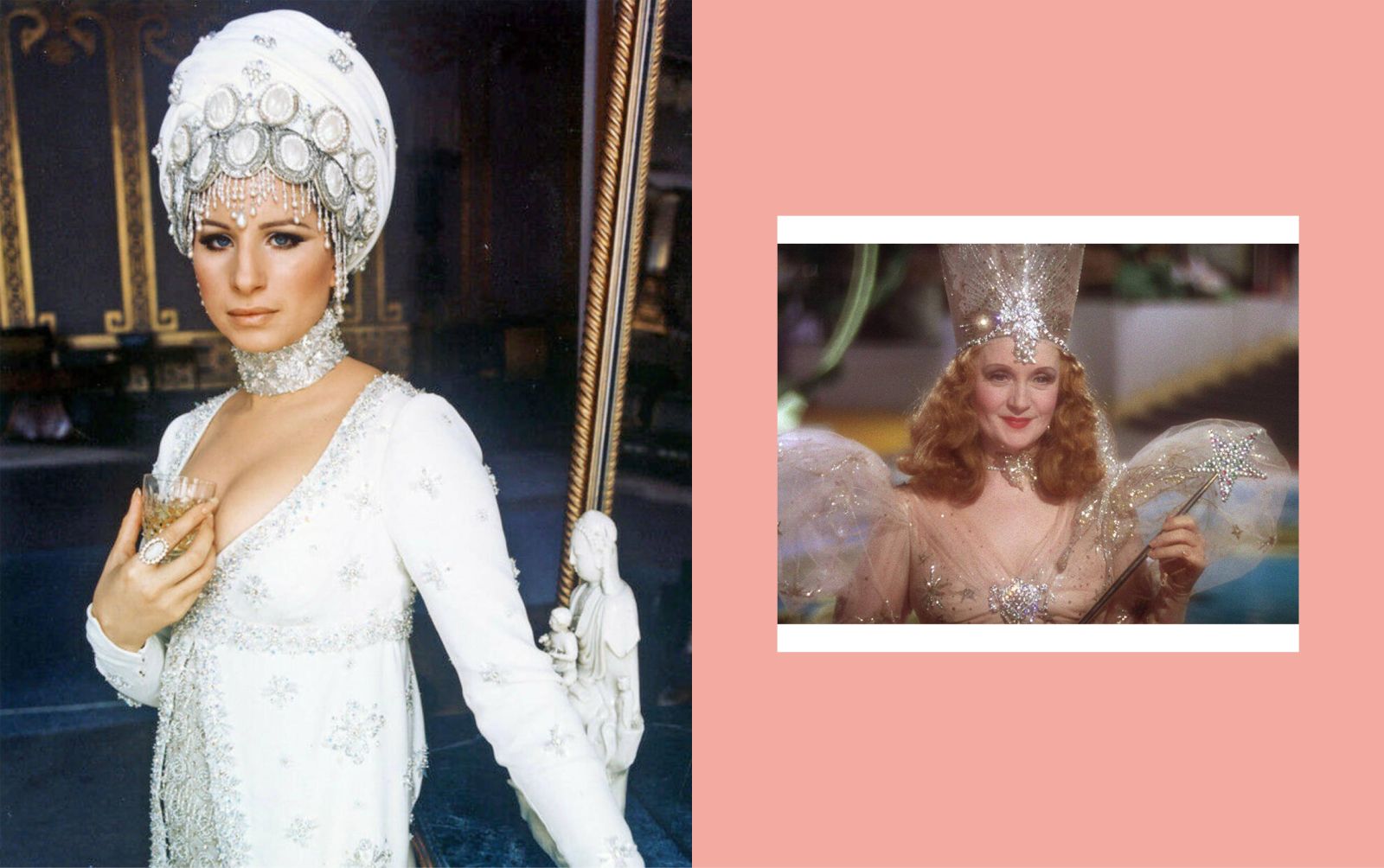

Do you have an early memory of costumes in film?

My first movie experience was probably The Wizard of Oz. As a kid, they used to show it every year on television. I didn’t realize that the second half was in color, because we only had a black-and-white television. I think I was pulled in by the imaginative things of the Munchkins and the lion. I was very much a television kid. I always joke about my misspent youth in front of the television.

Did any fashion designers help shape your aesthetic?

I give credit to a few very different designers. I just love the showbiz and glitter of Bob Mackie. I don’t get to use it often, but when I do, I think of Bob. But then there are the Italian designers, Piero Tosi, Milena Canonero—I just idolize her. Irene Sharaff, who did incredible things with palettes of color. And of course Adrian, who just had an endless imagination. There are motifs he used over and over again.

What was your first job out of college?

I’ve not actually worked in anything except costume. My years between undergraduate and graduate school, I worked as a shopper at Barbara Matera Ltd., which made all the Broadway clothes. So stars and big designers would come through. That was thrilling for me at 23. Then in my first [costume] job I was working for Carrie Robbins and Marlo Thomas, Elaine May, Peter Falk, Jeannie Berlin—who I’ve since worked with twice, on Inherent Vice and on The Fabelmans. I was never a PA, I was more of a design assistant. I did everything for Colleen Atwood for Married to the Mob—swatching, dyeing, just whatever she needed me to do. That was very early on. So my whole road to today has just been with an eye on what I wanted to do and making choices along the way that got me where I wanted to go.

Daniel Day-Lewis as Reynolds Woodcock in Phantom Thread

“I want them, when they look in a mirror, to feel like that person on the outside as well.”

Do directors come to you more often knowing the kind of look they want or are they hoping you’ll provide it?

I’ve been fortunate enough to work with directors who write their own material, so they have an image of a person in mind. Or there’s a character that they based [the story] on. But I find it very satisfying when they rely on me to interpret the written page and bring it to life. Once I get the script, I delve into it, doing as much research as I can to illustrate what these scenes might look like. It’s very ongoing. I start as soon as I sign on, and this is what I do in my evenings. It’s just fun for me. I’m curious to find a lot of images, and then the question is: What are we gonna do? What can I find that will evoke these moments to tell the story?

There was an [intricately beaded] dress that I got for Phantom Thread that I added chiffon sleeves to. It was supposed to be an early work by Reynolds. Sometimes you will find very unique pieces here. Originale. [Another] particular dress, I loved the collar so much, but the dress is quite big and it’s also silk crepe that’s 80 years old, so probably wouldn’t last a film shoot. But the collar’s in good shape. What I did was remove the collar—my cutter remade a dress [The Artist] actress Bérénice Bejo’s size and then we put the collar on it. So you’ve got a real period detail on a brand-new dress and that works perfectly. And then, before we return the dress, we just put it all back to the way we found it. I did another collar steal for Licorice Pizza. I’m very respectful of vintage clothes—I didn’t wanna cut it off or anything. There was no way we’d be able to re-create the beauty of a double-knit collar with little flowers on it.

What did your research material look like for Phantom Thread?

I’m always looking for an image that could evoke a moment in the film. I had photos of various London workrooms from around the period of Phantom Thread, and the wonderful discovery that a lot of the seamstresses wore lab coats when they were working. So we know we’re on the right track and how to represent the workroom at Reynolds Woodcock’s atelier. I used an image of Anthony Eden [as a reference] for Reynolds Woodcock, how he wears his clothes. Oddly enough, Eden had married a younger woman. There’s a shot that I think might have been their wedding, which was a great jumping off point for Reynolds and Alma’s wedding. I’m not gonna strictly copy it, but it evokes what it could look like in the film. And it helps me and it helps my assistants, and it helps the director.

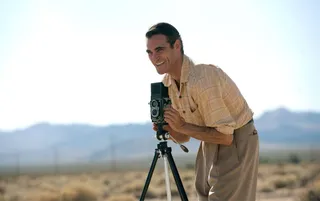

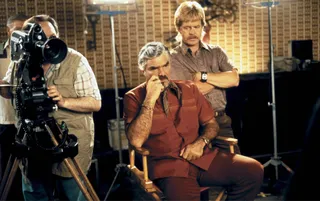

From left: The Master (2012), Licorice Pizza (2021), Boogie Nights (1997)

Do you scour flea markets and estate sales to try to find images?

Occasionally. There’s always a shoe box full of black-and-white photographs I’ll go through if I’m working on a specific project, because you’ll find snaps of how clothes were really worn at the period. And it’s not like you see it in a Hollywood movie! It’s kind of ill-fitting, like some young man is just on the cusp of manhood but his parents have bought him a suit that’s a little bigger so that he could grow into it—those are the kind of unique touches that I really like. Then sometimes there are people who come to mind. In Phantom Thread, Reynolds’s sister is played by Lesley Manville, and I thought Vivien Leigh was a good image for an English woman of that period. So you’re always looking for real people from the period to inspire you.

How do you make costumes look like real clothes?

I think it comes down to the photogenic quality of the clothes and the choices we make in [approximating] the randomness of real clothes. I do have a couple of tricks for using colors in a certain way to make it feel random. I won’t tell you what they are. They’re my secrets.

What types of films do you like to work on?

I’m drawn to films that want a very realistic look—not designed—which is funny, because I’m a costume designer. But there’s a challenge in that as well, of trying to do something but not getting caught at it, not making it look designed or planned, and making it seem very natural and very accessible. Paul Thomas Anderson always wants things to seem very natural. I’m fortunate enough right now to work with Paul Greengrass, and he comes from the documentary world. So while you are subtly slipping in design, and guiding the audience’s eye where to look, and also talking about the character through their clothes, you don’t want to get caught at it. You want it to seem very offhand and real.

From left: Funny Lady, dir. Herbert Ross, 1975; The Wizard of Oz, dir. Victor Fleming, 1939

Do a lot of your preferences or choices in clothes come from your own life?

Hopefully you bring something autobiographical to your work. When I was in high school, I worked in a coffee shop and I always wore these zip-up uniform tops. I used that for Dirk in Boogie Nights, an oversize kitchen smock. Then he’d have his regular clothes on underneath. So you’re bringing some of yourself and your own history in. I knew the period down cold, and I knew what Dirk was going to be gravitating toward as to what he thought was cool, because I was around the same age as Dirk in those years. I knew what I loved as a kid. And I had Dirk loving it too.

Paul [Thomas Anderson] had asked for [Burt Reynolds’s character] Jack to wear something that he could wear in the daytime and then wear to the disco at night. And then Reynolds chimed in saying he wanted to be dressed all in one color. And what’s great about it is that there are already so many pictures [of] the actual Burt in 1977. He was a man of that period. I actually went to Burt’s shirtmaker, who had clippings and swatches of what he had made in the ’70s, the fabrics that Burt liked. So I remade some of the fabrics. And at one point we were doing the New Year’s Eve scene and he looked at himself in the mirror and he goes, “I haven’t looked this good in 30 years.” And I knew I had him.

How important are the costumes as a tool for the actor to transform into the character?

A lot of actors who come from the stage want to be very grounded. So they’re very concerned about their shoes, because then they feel grounded and they walk a certain way. And the way you wear a pant, whether it’s high or low, can make you stand a different way. Joaquin Phoenix had this incredible pose in The Master where he kind of was like this [hunches over, hands on hips], and it was all about character. But would it have been the same had he not been wearing those high-waisted pleated pants? I always say that I give outer skin to that inside emotional stuff that the actor’s doing. So they may feel a certain way, but I want them, when they look in a mirror, to feel like that person on the outside as well.