The House that Bluth Built

By Kambole Campbell

The Secret of NIMH, dir. Don Bluth, 1982

The House that Bluth Built

How a studio founded by former Disney illustrators introduced new sophistication to animation

By Kambole Campbell

January 10, 2024

In the present-day animation landscape, where traditional pencil-on-paper work is perpetually on the verge of breathing its last breath, The Secret of NIMH (1982) feels like a small miracle. The handmade, technical experimentation and the sheer amount of work that went into it was a rarity at the time of its release, a moment when the dominant force in the medium, Walt Disney Animation Studios, was at a low ebb in its theatrical output. The director of NIMH, the legendary Don Bluth, became known as “a considerable thorn in Disney’s side during the 1980s,” according to Noel Brown in his comprehensive book Contemporary Hollywood Animation. A former Disney animator, Bluth made films like An American Tail, which proved to be some of the most profitable non-Disney animated films of the era.

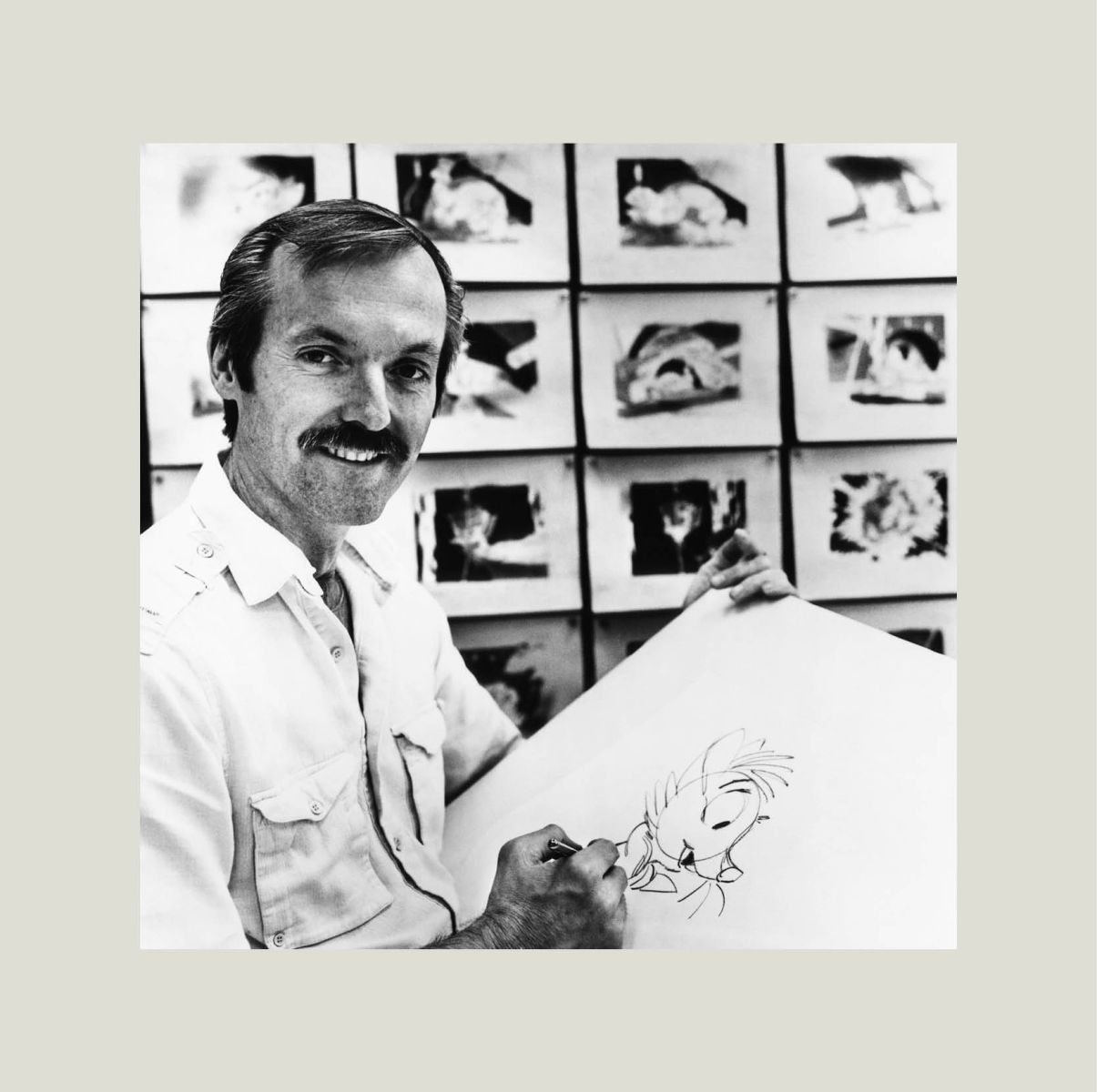

Don Bluth with an illustration from The Secret of NIMH, 1982

Bluth left Disney in 1979 and had an arduous start as an independent animator: His first film, the 29-minute Banjo the Woodpile Cat, was made in his garage. Don Bluth Productions, launched in 1979, was founded alongside fellow former Disney artists including his co-producers Gary Goldman and John Pomeroy. Their company aspired to create the kind of films they believed Disney was no longer interested in producing “because the corporate structure was just too calcified and we couldn’t fix it,” Bluth reflected in an interview.

The studio’s first feature, 1982’s The Secret of NIMH, received critical praise but failed to make a big box office splash upon its release. Over time, however, this adaptation of Robert C. O’Brien’s 1971 children’s story about the widowed field mouse Mrs. Frisby’s (redubbed Mrs. Brisby in the films) desperate attempts to cure her sick child has been memorialized as a key moment in animation history and a sign of Disney’s faltering grip on industry dominance. NIMH marked the beginning of a cartoon-mouse arms race between Bluth and Disney, with an exchange of films during the ’80s, like Disney’s The Great Mouse Detective and Bluth’s An American Tail, released within months of each other. The competition snapped Disney out of its stupor, and the behemoth began to put more resources into its animated feature productions in response. In Demystifying Disney, author Chris Pallant cites Bluth as “[the one] who proved most influential in prompting the Disney Renaissance.”

From left: The Great Mouse Detective, dirs. Burny Mattinson, John Musker, Ron Clements and David Michener, 1986; An American Tail, dir. Don Bluth, 1986

That began with NIMH and the film’s embrace of what Pallant refers to as a recollection of “the finely detailed hyperrealism of the Disney-Formalist period.” Seeking a return to the sophisticated aesthetic of Disney’s golden age—Fantasia, Pinocchio, Bambi, all from the 1940s—which Disney had abandoned due to cost-cutting, Bluth’s team iterated on techniques such as rotoscoping that merge verisimilitude and broad expressionism: The animals move like their real-world counterparts but are given a layer of anthropomorphism, a hand-drawn window into their thoughts and feelings. As Bluth himself has noted, they “use[d] the tracings as a guide, sometimes altering or exaggerating them 50 percent.”

NIMH’s strange and sometimes harrowing story is told in the guise of a pastoral fable. Field mouse Mrs. Brisby has a cozy home in a cinder block tucked under burrows and long grass near a farmhouse inhabited by humans. Initially it feels like an idyll, but it doesn’t take long for the stakes to become tangible. Brisby’s husband, Jonathan, a mouse freedom fighter, is dead, and she must care for the family without him. Her younger son, Timmy, has pneumonia. Worse still, they can’t risk moving him from bed for three weeks, which puts them well past the threshold of “moving day.”

But moving day is even worse than it sounds, a time when the plows turn over the fields, destroying the homes of the nestled animals. It feels downright apocalyptic: The skies are a tapestry of contrasting colors—luminous blue and green hues to hellish, fiery reds—while the twisting roots and buried stone structures that Mrs. Brisby travels through are given a much sharper definition, through deep shadows and well-defined lines. There’s a delightful inventiveness in exploring the human world from the animal perspective, which, according to Bluth, was partially imagined through the help of miniature sets built before the layout stage. Everyday locations and objects are blown up to intimidating scale, from the puddles that appear like swamps to an old grain-storage tank that recalls Gothic architecture, with a repurposed lantern serving as an elevator to reach it. That sense of scale doesn’t only apply to the structures within the context of the film; there were only three or four artists covering about a thousand backgrounds for the film.

Timothy in The Secret of NIMH

“For an audience trained by decades of cartoons not to bat an eye at anthropomorphic animals, it’s almost more unusual to encounter a cartoon mouse’s ability to talk depicted as something unnatural and even traumatic.”

Much of NIMH has a layer of uncanniness to its art direction, as Bluth depicts natural environments in vaguely unnatural colors, with red and green lights inexplicably seeping from undetermined sources (achieved via backlit animation cels)—all of which serve to make the characters stand out more. It’s particularly clear when they walk into an area where they don’t belong. Even earthy elements are made to look supernatural through the Bluth team’s iterations on traditional techniques—the artist has spoken about how the fire in his film is also different through backlighting. Not only did they paint the fire “but also cut out a design of that fire, put a colored gel over the top, backlit it with a very strong light, backed the camera up and passed the film over this backlit process a second time with the lens out of focus. It makes the fire much ‘hotter’ and also gives it a halo effect.” The creativity of their effects work gives the world that Mrs. Brisby is exploring a sense of life equal to the motions of its characters.

The characters themselves are expressive in a different manner, each with their own idiosyncratic gait that conveys a charming balance between believability and cartoonishness. It doesn’t feel like an understatement to call it some of the most beautiful animation ever drawn, at once sublime and horrifying (in a manner appropriate for children). At one stage Mrs. Brisby is instructed to visit the Great Owl for guidance, and his dwelling within the hollow of a large, cavernous tree in the forest is delightfully grotesque: Small bones drop from the ceiling with each flap of the owl’s wings. On the same journey, Mrs. Brisby visits rats within a thorny bush that envelopes the whole scene—the locations are full of frightful jagged lines and otherworldly glows. Here Bluth introduces the story’s more fantastical elements, like the secret society of rats arguing in a gilded underground government chamber. This isn’t to overstate the film’s seriousness, though. Throughout, Mrs. Brisby is accompanied by Jeremy, an oafish and clumsy crow who means well but comically stumbles through absolutely every scene.

From left: Mrs. Brisby visits Nicodemus in The Secret of NIMH; still from The Great Mouse Detective

The film’s sillier companions and its storybook qualities belie some surprisingly dark subplots, such as a (rather harrowing) sequence depicting animal testing in a lab in the city—NIMH, as fantastical as that sounds, is actually an acronym for the National Institute of Mental Health. Those experiments are what led to the animals’ acquiring the ability to read and think, a plotline that ties into Mrs. Brisby’s backstory, unbeknownst to her, as the inhabitants of the land around the farm had all fled from imprisonment at the NIMH. For an audience trained by decades of cartoons not to bat an eye at anthropomorphic animals, it’s almost more unusual to encounter a cartoon mouse’s ability to talk depicted as something unnatural and even traumatic. It’s one part of the quiet discomfort NIMH fosters. The magical idea that field mice and farm animals have their own little society is undermined by a dose of reality (if you can call it that): the suggestion that these evolutions are the by-product of human interference with the natural world. In gaining human intelligence and building their own mirroring societies, so too do the rats take on humanity’s worst traits. A subplot of courtroom intrigue sees one power-hungry rat kill and climb over his own kind to satisfy vain ambition. Such moments are glimpses into the adult world, though without compromising the fantasy or becoming overly instructive or didactic. Witnessing that darkness is vitally important to children’s stories—minor preparations for the moral complications of later life but also representative of an uncondescending trust in an audience’s capability to perceive more complex stories.

The Secret of NIMH was one of the most important American animated films of its decade. It represented a renewal of American animation as well as a mission statement for Bluth’s philosophy: the expressive power of the medium, and the importance of it being done with care and detail. Though it didn’t live up to financial expectations on release, NIMH has survived the test of time, its commitment to traditional craft sparking artistic passion across the industry. But Bluth’s work also represented the potential for a broader range of animated stories. The Secret of NIMH showed that children’s fare could take on harsh themes without becoming sanitized or compromised.

Fievel in An American Tail