Scorsese’s Kiss

By Alexander Chee

After Hours, dir. Martin Scorsese, 1985

The Kiss

Alexander Chee

Is Scorsese’s After Hours secretly the gayest film of the 1980s?

August 25, 2023

The scene opens with a close-up: a shot of Jack Daniel’s being poured into a glass, a black-leather-gloved hand closes around it as the bartender lifts the bottle to indicate the pour is done. The camera drifts back to reveal the gloved hand and the tanned muscular arm it belongs to (a black leather strap around the biceps), along with sunglasses, then black leather caps on two dark-haired men sitting next to each other on barstools. They toast and knock back the shots in the time it takes a young man to enter and sit down in front of the bartender.

As the bartender and the young man talk, the two leathermen are visible in the middle distance between them. The normal “straight” men in the foreground make a strange frame for what happens next: The leathermen begin stroking each other’s chests. Their vests are open, and all of it is so heartfelt, so natural, it is shockingly erotic as their mouths meet.

I paused and rewound the film to be sure I understood what was happening. I didn’t. There was just the kiss, like a downbeat in a song emerging from the background bass, a soundtrack pivot that often signals new characters, a new direction.

The phone in the bar rings. The leathermen have kissed and pawed each other for more than a minute by this point. The bartender answers, is silent, and the camera falls on his ass, as if we are in the young man’s POV and he’s ogling it. Is he questioning his sexuality? But no. We learn the bartender’s girlfriend has just taken her life. Her name is Marcy, the same name as that of the young woman the film’s protagonist, Paul, has followed downtown. Paul was at her bedside a little over an hour earlier, having found her dead. The two leathermen finally stop kissing and instead hold each other while trying to offer consolation and advice to the distraught bartender. As the young man realizes the bartender’s girlfriend is the same young woman he just met, he freezes, uncertain of how to respond. “What can you say? After all, it wasn’t your fault,” one of the leatherman offers, exuding compassion as the bartender blames himself for her death. All of their tenderness in this moment is earthly and real. The scene ends when the young man leaves.

We don’t see the leathermen again.

I’ve mostly avoided Martin Scorsese films. I don’t know how to care about the kind of men that the director typically takes for his chief subjects, men who only know how to express themselves violently or not at all. But 1985’s After Hours is a different kind of Scorsese film. It looks like most of the films I rewatch from the 1980s, the ones I loved when I saw them the first time around. Plus, it stars the boyish Griffin Dunne as the awkward everyman hero, Paul.

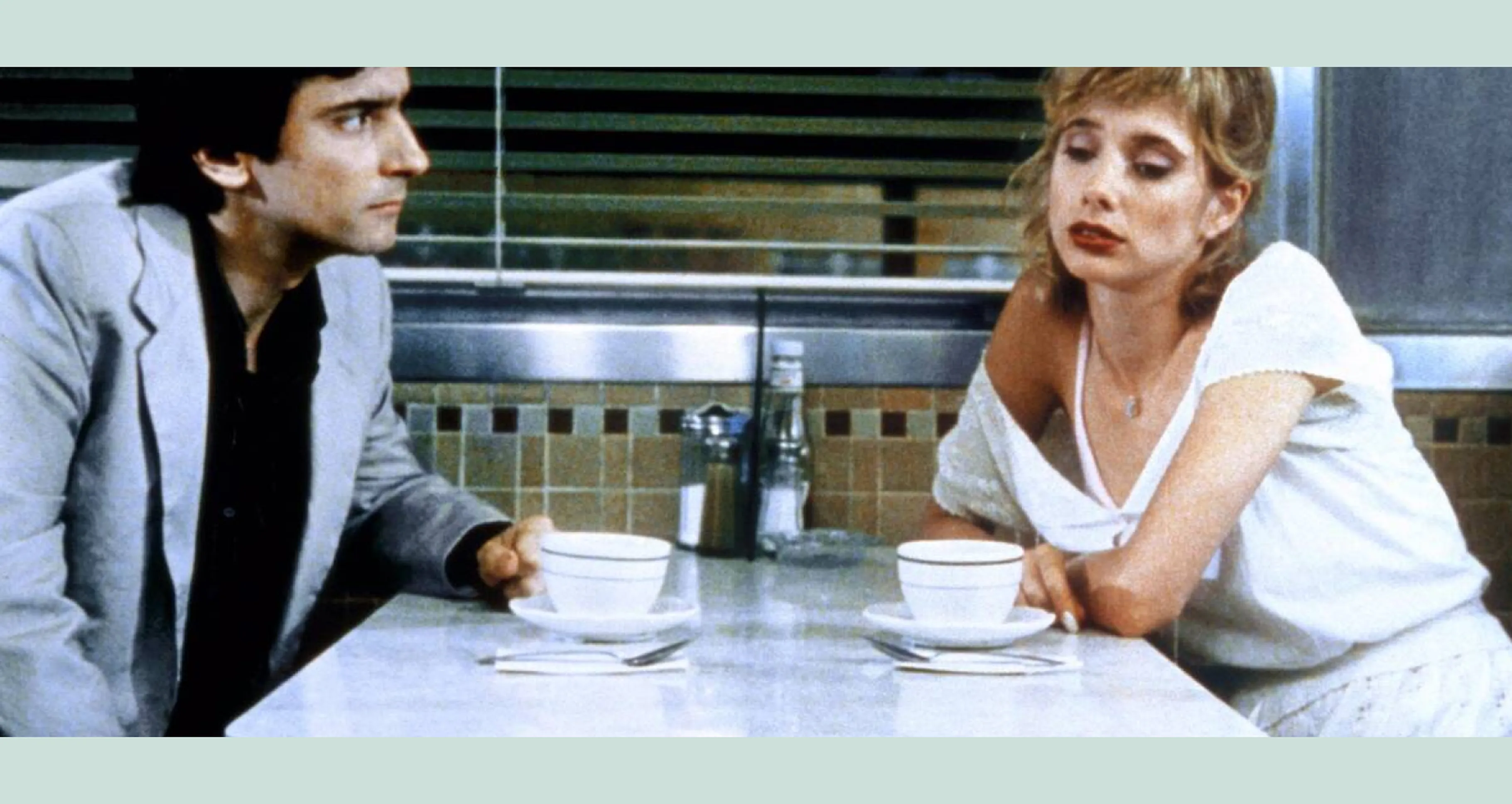

The film begins with Paul in the kind of corporate office scene dreamed up by screenwriters who have never actually had an office job themselves: a giant room full of identical desks, with identical screens and keyboards. Paul’s job, likewise, is more the approximation of an office job, almost like science fiction, the actor dressed in a plain baggy suit. Paul’s title is Word Processor. He goes home and then eats dinner at a Manhattan diner where he reads Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer across from an attractive young woman, Marcy (Rosanna Arquette), who locks eyes with him and quotes the novel’s beginning from memory. A slow smile moves over his face in recognition. The novel just happens to be a favorite of hers. And so we enter a trail of coincidences that will continue over the remaining hour and a half and turn Paul’s world inside out—and ours as well. It’s a classic Hollywood comedy setup for a romance, and what follows, at first, promises to seal the deal.

“IT EXISTS IN A KIND OF

CULTURAL BLIND SPOT

THAT IS DRAMATICALLY

UNIMPORTANT TO THE STORY

EVEN AS IT

STEALS THE SHOW.”

The two have an awkward conversation about a series of plaster of paris bagel-and-cream-cheese sculptures that Marcy’s roommate makes. They both pretend to act interested in his offer to buy a sculpture, and so she gives him her roommate’s number, which of course is also her number, back in the landline days of 1985. Later, back in his apartment, looking at his Henry Miller novel (a groundbreaking work of erotic intensity), Paul decides to give Marcy a call. She suggests he come downtown on the pretext of buying one of the sculptures and gives him the address. He smiles, hangs up the phone, and then catches a cab. Watching After Hours 38 years after its release, it’s remarkable how the film captures the way our lives were so rigidly constructed back then, in the pre-Internet 1980s. We lacked for ATMs, cell phones and credit cards. Taxis took only cash, through the cradle in the safety window separating passenger and driver. Intercoms and buzzers barely worked. Marcy’s roommate (Linda Fiorentino, perhaps the only costar who could make Arquette look mousy) throws down the keys to the apartment with the offhand nonchalance I remembered from all of my downtown friends in that period.

As Paul makes his way to Soho, the film begins to resemble a dream. In a dream, it makes sense that the only money that you had would fly out the window of a taxi. Or that the driver, on getting you downtown, would just shake his head and then drive off. While you wait for the woman who invited you downtown to return from a trip to a 24-hour pharmacy, her roommate would probably try to seduce you—getting you to take off your shirt, asking you for a massage, mentioning that she doesn’t have many scars. The roommate would be working on a sculpture of someone who seems to be screaming in the agony of being burned alive. The young woman, when she returns, would speak of fighting “with a friend.” Then, after a couple of times aimlessly leaving and returning to the apartment where at different points you get spooked smoking a joint and the woman you’re interested in overdoses on pills, you eventually return to the local bar that makes sense only in a dream.

And this is where the dream, for me at least, breaks. And another one begins.

Griffin Dunne and Rosanna Arquette in After Hours

When Paul first walks through the Soho streets to the bar, it reminded me of all the completely random nights I had in New York City in the ’80s, when it seemed like just about anything could happen. The good part of that was an exhilarating rush. The bad part was a terrifying feeling like the ground was dropping out from under your feet. Maybe the cab refused to take you to Williamsburg and left you in a part of the city where you knew no one. Maybe the street seemed eerily empty, and block by block changed from serenely empty to ominous and back again. Or maybe it was raining, as in the film, and like Paul, you are soaked through, no raincoat, no cash, no umbrella, maybe not even your own keys. You see, like he does, a glowing sign for a refuge named the Terminal Bar, which of course, is also gently ominous.

The second time Paul enters the bar is the scene with the kiss.

The bartender is framed by the bar mirror. The bar’s Art Deco light fixtures exude a mint glow, strangely refined, juxtaposing with the branded Lite beer lampshade over the pool table. The tables are linoleum, a plain beige. The walls are covered in wood paneling. The other sources of light are the cigarette machine and the jukebox, and it is like many bars I remember from New York—a few of them still in operation—that look as if they were once much nicer, and that every ten years the owner tries to add a touch or two, aesthetic gestures that quickly sink back into the retro mire.

Paul sits on a stool as the bartender chews him out in a way that still feels out of that same dream—he is played by John Heard, a blandly attractive blond man, taller than most of the people in the film, and the manner of his outrage is the stilted concern someone musters when he realizes he may not remember how to be angry. As they talk, the two leathermen kiss in between them.

.png)

Linda Fiorentino and Griffin Dunne in After Hours

After all the awkward movements of the previous heterosexual encounters, along with the strange stop-start motion of the dialogue, this kiss is the first successful intimate erotic coupling in the course of the film. As the kiss begins, the bartender asks Paul if he’d like a drink, and Paul replies, “You don’t happen to have any powerful aphrodisiacs back there, do you?” He is not making a joke about these men but about himself, in a pointed reference to their obvious chemistry. Heterosexuality in After Hours has thus far been all awkward workarounds, a “here’s my roommate’s number if you want to buy her plaster of paris bagel-and-cream-cheese paperweights” dance—all failed sex, death and humiliation. If I had planned to make a film that indicted compulsory heterosexuality, it would look something like this one set in 1985.

For the rest of the film, and long after it ended, I was haunted by the intimacy between the leathermen. The way the scene had felt as if they were in their own film. These men, celebrating something just at the edge of our vision, might have been toasting a reunion after a long time apart. Maybe they had accidentally found each other again that night, despite their own set of coincidences that kept them apart. But in 1985, or even 2015, dressed as they were, their long, very normal, very hot onscreen kiss wouldn’t be likely to appear anywhere outside of a porn movie.

At best, the leather fetish community and SM community are typically used as props in mainstream films, straight or gay, when a filmmaker hopes to telegraph that they are “edgy.” Their figures are usually symbolic, metaphorical, a signal of some kind related to forbidden sex. A domestic drama about two male members of the leather community—I won’t say it doesn’t exist, but I’ve never seen it. The closest so far is Dry Wind (Vento Seco), a 2020 Brazilian drama by director Daniel Nolasco, set mainly at a fertilizer factory, where a love triangle ends in a threesome that seems likely to become a throuple, and fetish and domination exist in a continuum of sexual possibilities. Nolasco’s intensely stylized documentary, 2019’s Mr. Leather, about a dramatic dust-up within the Brazilian leather community, also comes very close to what I speak of. But for much of the last three decades and right up to today, queer narrative films—even the bravest ones, like Weekend or 120 BPM —have told stories primarily about singles looking for romance, or couples hoping to experience some shred of a conventional heteronormative relationship.

The leathermen aren’t the only representations of queer identity in After Hours. One third of the way into the film, Paul briefly meets two gay men in a Soho stairwell who ask him why he’s in the building, a completely normal New York interaction that doesn’t appear in realistic films enough. One of the actors, playwright Victor Bumbalo, cast as Neighbor #2, spoke to New York magazine about the film in 2012, saying Scorsese’s instructions were “Please don’t act.” In the film’s credits, the leathermen are identified as Joel Jason and Rand Carr, Biker #1 and Biker #2. Very little is available about these actors online, and most reviews of the film don’t mention the kiss at all. It exists in a kind of cultural blind spot, a kiss that is dramatically unimportant to the story even as it steals the show.

.png)

Griffin Dunne and John Heard in After Hours

It is uncanny to put a stopwatch on a kiss—it feels inimical to the enterprise—but I was trying to understand what I had seen, the strange calculus I was engaged in because of the way a moment between these two minor characters in a seemingly “straight” film was somehow more intense than, say, the taboo-breaking kisses in the London gay film My Beautiful Laundrette, released the same year as After Hours. Starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Gordon Warnecke as two young lovers who break sexual, racial and class divides, it proved to be one of a group of watershed films that put a gay romantic storyline front and center. And so I went back to My Beautiful Laundrette to time the kisses between the two leads, just to see if I was imagining it, and found that not only were the kissing scenes not nearly as long as the one between the leathermen, they were also not as clearly visible. Only the 1980 German film Taxi zum Klo and the later 1983 French film The Wounded Man (L’homme blessé) go farther, although these were classified as distinctly foreign art-house films and never received the widespread domestic release that After Hours did.

I am still absorbing the way these two minor characters in this “straight” film were allowed to have a long, sensual queer kiss that was denied in the films that laid the foundations of what we would call New Queer Cinema. Film critic B. Ruby Rich had called 1985 the “defining moment” of New Queer Cinema, and it did feel like it to me at the time, though there were many films in the years before and after. Watching Mala Noche, Another Country, My Beautiful Laundrette, Kiss of the Spider Woman, I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, Desert Hearts and Law of Desire, I knew I was in the foyer of my adult gay artistic life, seeing glimpses not only of lives from all over the world, but a life I was anxious to start, a life as an artist telling stories like these, where our lives are more than backdrops. This was the most exciting thing I could think of doing and it still is. I just have to wonder what it would have meant to me to see this film then. To have the reaction I’m having now, then.

Gay Pride celebrations in San Francisco

If Paul ever questions his sexuality, it is a private actor’s motivation that Dunne has never publicly shared. After Paul leaves the bar, he continues on through 1980s-era Soho, through the mix of nightclubs and the apartments of various women he meets, just wanting to get home. As he doesn’t even have enough change for a subway fare, he grows increasingly desperate, and in this way the film has a deceptively simple structure—comedy ensuing when each setup strung together in the course of night goes hopelessly wrong and dissolves into further chaos. Paul is bad at being a hustler, or even nice in the face of his troubles. Eventually, he enrages the citizens of Soho to the point that an angry mob chases him into an art party that’s no actual party—just a lone attractive older woman artist named June at a nightclub. She seems taken in by his being a nice guy. He is of course too exhausted to be desperate, another kind of desperation.

“Why are you doing this?” June asks. “You flirt with me, you share your cigarette with me, you dance with me. You’re nice to me. Why are you doing this?”

“I want to live,” Paul says, as Peggy Lee’s “Is That All There Is?” plays on the jukebox—a song he chose with what seems to be his last quarter. “I just want to live.” He is too exhausted to be desperate and so he has managed, somehow, to hustle her. But the night isn’t yet over. The mob finds her and Paul and so she hides him inside of a plaster statue, which is then stolen by thieves. The statue falls out of the van as it goes around a turn, releasing him as it shatters. Paul dusts himself off as he takes in where he is: right in front of his office, which is opening up for the day.

The joke is on him, he understands. He still has to go to work. The first to arrive, he sits down at his desk as his other colleagues filter in. Only his screen welcomes him back, in what feels eerily like a prequel to the current sci-fi television office drama Severance, with letters typing themselves as he watches: Good morning, Paul.

In the end, this is a dream about lost money and what we must do to get it back, if we even can. That’s as apt a way as any to describe America as it was then and is now, and maybe always will be. Scorsese may also have experienced the film as a dream about lost money: He described After Hours as rescuing his career, in an interview in Esquire commemorating the film’s 35th anniversary. He had become “box office poison” due to The King of Comedy’s failure at the box office and needed to find his filmmaking spirit again after the defeat. He picked the script of a young newcomer, Joseph Minion, who’d gotten it to Dunne. Scorsese was able to wrestle the project away from Tim Burton, who didn’t seem to be harmed by letting it go, and the Geffen Company and Warner Bros. signed off on a comparatively low budget of $4.5 million. The film made $10.6 million, per IMDb. Was that enough of a victory? It was. The King of Comedy had made just over $2.5 million on a $20 million budget.

But none of these successes matter as much to me as the kiss. Is the final lesson that we could only be ourselves as gay people on screen if we were anonymous, not played by stars, figures that were neither in the foreground nor the background, and absolutely not a part of the story? The famous director had given the instruction “Please don’t act.” After Hours is so almost a film about a man who fails so badly at being straight that he could have given up, given in. For now, though, I retroactively make Scorsese a hero, to me, and this film his underrecognized part of New Queer Cinema’s historic year.