The Point Break Exception

By Thad Ziolkowski

Point Break, dir. Kathryn Bigelow, 1991

The Point Break Exception

One surfing film rides high above all the others. What is the key to its awesomeness?

By Thad Ziolkowski

November 1, 2023

There are three kinds of surf film. The most numerous but least mainstream are those made on a shoestring budget by and for surfers, which jettison any overarching narrative to concentrate on ride after pornlike ride, such as the aptly titled Repeater (2023). Then there are the big-budget documentaries, like the easygoing The Endless Summer (1966) or HBO’s reality-TV saga 100 Foot Wave (2021–), which succeed in doing rough justice to the sport and make waves with the general public. Finally there are the usually groan-inducing surf-themed Hollywood productions, a seemingly cursed subgenre spanning from Gidget (1959) to Chasing Mavericks (2012) that always get surfing wrong, whether in the water or on the beach.

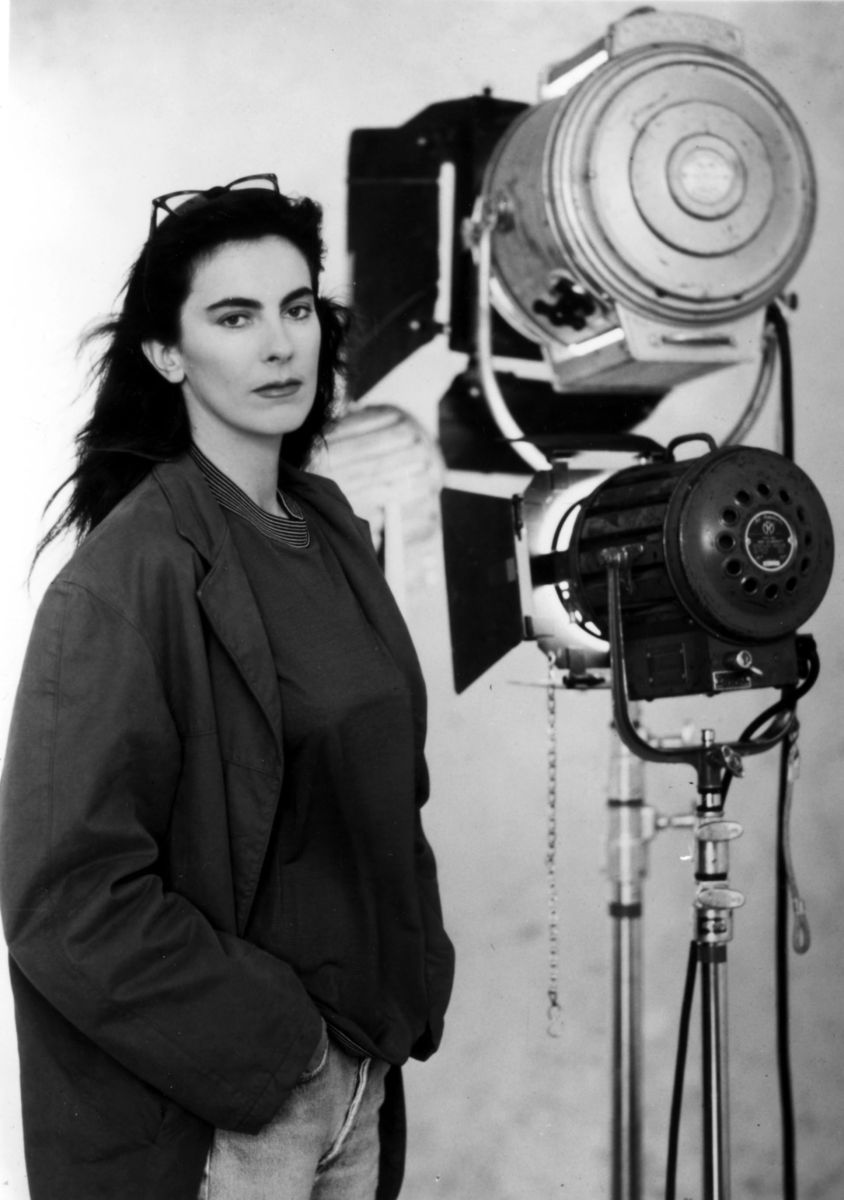

Kathryn Bigelow promoting Point Break, 1991

For that third category, which requires a cinematic storyline, the difficulty lies in the very essence of surfing, which is a cyclical, wave-after-wave repetition compulsion. Hardcore films like Repeater simply reflect this reality without apology, while popularizing documentaries fill in the blanks with interviews, profiles, lifestyle and travelogs, capturing surfers’ low-key, rueful humor born of being regularly humbled by the ocean. Hollywood, meanwhile, fully seduced by the subculture’s cool along with the peerless eye candy of surf-action footage, tends to overcompensate for the absence of an intrinsic arc or telos with obvious devices like an all-consuming big-wave climax.

It’s not that surfers aren’t obsessive. It’s just that Hollywood melodramatizes the monomania as if worried the film as a whole will otherwise be illegible or dull. Surfers are neither characteristically macho nor mystically serene; they’re childlike—overgrown enthusiasts, eternal groms. What keeps them so enviably young and excited? The addictive full-body neurochemical rush of riding a moving band of ocean energy, which can often lead into—though also out of—drug and substance addiction. But the shifting doubleness of this truth resists the pithy classifications that work in studio-pitch meetings.

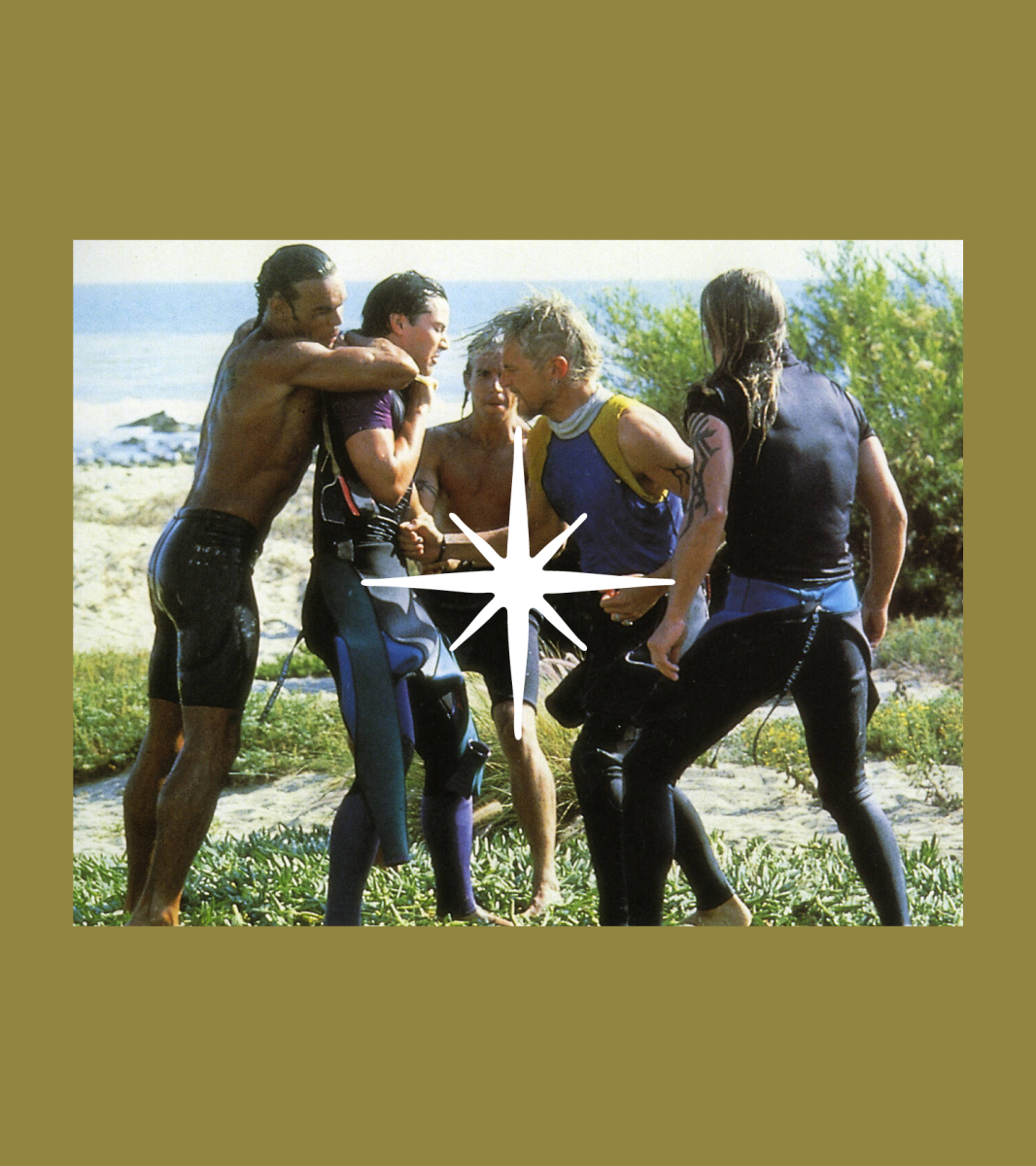

From left: Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze in Point Break; the Ex-Presidents

To be available whenever a swell pops up, hardcore surfers take seasonal and temporary jobs—restaurant and construction work, lawn care. They are what anthropologist Victor Turner calls “liminal personae”—living on the margins of society in a state of lowliness and invisibility: the homeless, monks, addicts and criminals are other examples. (A significant part of what lifts the woman-empowered Blue Crush [2002] above the usual level of Hollywood surf films is the realism of the hotel-room cleaning that the main characters do to get by.) To maintain their perch in this threshold realm, surfers may occasionally turn to crime, particularly drug-running. In the ’60s and ’70s smuggling hash and coke inside boards was a favored technique, as evidenced in the 1972 acid-addled art film Rainbow Bridge, featuring Jimi Hendrix. Charismatic ’60s icon Miki Dora, who found steady work as a stunt double in many early surf films, is as legendary for his scamming (writing bad checks, forging airline tickets) as for his surfing, and at least one major surf brand got its seed money from the drug trade.

So it makes sense that of all the surf-themed Hollywood films attempted since Gidget, the quixotic, razor-sharp, generation-defining 1991 masterpiece Point Break achieves its success precisely by plugging into the powerful circuit linking surfing and crime—in this case, a series of brash, adrenaline-pumping bank robberies. Director Kathryn Bigelow, who trained as a fine artist at the San Francisco Art Institute and the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Independent Study Program in New York and lived in Soho in the 1970s, during the heyday of appropriationism, is less interested in innovation per se than in playing with genre conventions (a pair of earlier features, the biker drama The Loveless and the vampire Western Near Dark, also hinge on itinerant subcultures living on the margins of society). It’s Bigelow’s detached, almost formalist sensibility that is the source of Point Break’s superiority, giving her license to mash the Hollywood buddy surf film with the bank-heist subgenre, crowding out the sappy tendencies of surf-themed films with the on-the-clock rigors of an action flick.

Surfers marking their territory in Point Break

“The surf zone is itself a liminal space,

neither land nor open ocean,

and Bigelow repeatedly

exploits the dreamy,

identity-blurring property of this realm.”

The plot is streamlined, fast-paced and stylized: Rookie FBI agent Johnny Utah (Keanu Reeves), a former star college quarterback, joins the Los Angeles bureau, where he is assigned to work with veteran Angelo Pappas (Gary Busey, who coincidentally or not also co-starred in the dreadful 1978 surf film Big Wednesday). Their first case is a bank robbery carried out by the notorious Ex-Presidents gang, so-called because they wear rubber masks of LBJ, Nixon, Carter and Reagan. These leering props have an outsize power, bringing to the film a thrilling political-theatrical edge reminiscent of the Guerrilla Girls, the feminist art collective founded in 1985 whose members wear rubber gorilla hood masks (in a visual pun) in their anonymous protests. The difference being that the Ex-Presidents’ masks lend the thieves a nightmarish authority and legitimacy, deliberately playing up the confusion between right and wrong.

The gang’s MO involves only stealing the cash in the teller drawers, thereby keeping each robbery down to ninety seconds and evading capture. Because of the tan lines on the ass of a mooning robber and the fact that their crimes occur only in summer, Pappas believes the Ex-Presidents are surfers filching just enough to fund the annual cost of their peripatetic lifestyle. Pappas is right (note that it’s a cyclical crime spree, renewed in summer). But this theory is the department joke: How could such a sophisticated, self-disciplined gang possibly be made up of surfers, who are as everyone knows airheads, Jeff Spicolis? “Hang ten, Pappas!” one of the FBI agents mocks. “Like, totally rad, dude!”

But Utah becomes a believer and agrees to learn to surf in order to infiltrate the gang and bring it down. He buys a board drenched in a bright flame motif and undergoes the first stage of a classic initiation when the androgynous, young surf-shop clerk remarks dryly, “Hey, man, a lot of guys your age are learning to surf. That’s cool. There’s nothing wrong with it.”

“I’m 25,” a taken-aback Utah points out.

“That’s what I’m saying,” the clerk replies. “It’s never too late.”

This is both good realism and a nod to the fact that surfing is a deceptively difficult sport best learned young, when the ego is most resilient and free time in abundance. Utah is what’s called a VAL—a vulnerable adult learner—and Bigelow has sadistic fun putting him through a wipeout sequence in which he’s saved from drowning by the film’s love interest, Tyler (Lori Petty). When Utah is accepted into the Ex-Presidents it’s not because he’s fooling anyone with his surf skills, which are nonexistent, but because the leader, Bodhi (Patrick Swayze), recognizes Utah as a former star quarterback. (That a hardcore surfer would follow college ball is implausible, but never mind.)

From left: Blue Crush, dir. John Stockwell, 2002; Big Wednesday, dir. John Milius, 1978; The Endless Summer, dir. Bruce Brown, 1966; Gidget, dir. Paul Wendkos, 1959

What Bodhi also recognizes in Utah is a kindred spirit—a fellow adrenaline junkie. And as he learns to surf, the thrill-seeking, anarchic side of Utah is drawn to the fore by Bodhi’s charismatic spell. “Hope you’re not buying into this banzai bullshit,” Tyler warns. But Utah is very much buying, as is Bigelow herself, who is at once repelled and riveted by testosterone-soaked masculinity, as evidenced not only here but in her subsequent films The Hurt Locker (2008) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012). Male violence is in effect Bigelow’s raw, volatile material and what’s remarkable about Point Break is how that violence—of the bank robberies and gory gunplay, of the fight scenes and the football played on the beach early on—is sublimated into the balletic power of wave-riding. While there is one scene built around localism and toxic male territorialism, the surfer gang that attacks Utah for straying into their turf is carefully distinguished from the communal Ex-Presidents, who make a point of sharing waves in a moonlit-drenched night-surfing scene—and note that what tips off Utah that his new surf buddies are the bank robbers is the signature mooning of one of the gang: an act that mocks but also exposes and makes vulnerable.

In Point Break the Utah-Bodhi pairing is Bigelow’s variation on a perennial theme of the genre: the secret sameness of cops and robbers, how hard it is to tell one from another in the half-light border of law and lawlessness. The long-haired androgyny of the male surfers and short-haired androgyny of Tyler strikes a similar chord in a different register—who is male, who is female? Bigelow establishes this ambivalent mood in the film’s opening sequence of hissing amber shorebreak, in which the names of the leads appear and merge followed by a slow-motion montage of some of the best surfers of the day, their faces masked by deep shadow. The surf zone is itself a liminal space, neither land nor open ocean, and Bigelow repeatedly exploits the dreamy, identity-blurring property of this realm.

Repeater, dir. Wade Carroll, 2023

Ultimately the blurred distinction between cops and robbers is brought to a head when Utah is forced to participate in the gang’s final robbery of the summer—shades of Patty Hearst.

“I am an FBI agent!” an outraged Utah reminds Bodhi on the way to the bank.

“I know, man, isn’t it wild?” Bodhi replies. “But you know, that’s what makes it great, Johnny. We can exist on a different plane—we can make our own rules.” This is Bodhi introducing improvisation, which is at the heart of surfing, to the realm of ethics—a state of play beyond good and evil.

But once inside the bank Bodhi breaks the gang’s cardinal rule, robbing the vault rather than sticking to the 90-second teller-drawer-only plan—the foolproof method having lost its capacity to provide a killer rush. He is offending the cyclical nature of surfing by getting greedy. The result is a bloodbath in which one of the gang is killed. Bodhi escapes to a getaway plane, pursued by Utah and Pappas, who is fatally shot on the runway.

From left: The Ex-Presidents in action; poster for The Endless Summer

Here, Bigelow builds the chief climax around skydiving instead of surfing. The substitution works well: Skydiving rhymes with surfing as a thrill-junkie activity conducted in liminal wilderness—open sky over desert in this scene, rather than the surf zone between land and ocean. This weightlessness is the broad aesthetic achievement of the film and at the heart of surfing, a specific heady mood of carnivalesque transgression and possibility—wearing masks, slipping the bonds of conventional arrangements and even identities. What’s so intoxicating and addictive about surfing is the feeling of gravity-free glide and lift—freefalling down the face of a wave, turning at the bottom and lofting upward. Who am I, riding a wave? I am not my terrestrial self, I am some clarified creature or spirit. In Point Break this weightlessness and crime merge, as when robbing a bank the Ex-Presidents leap up onto the counters like they’re popping to their feet on a board. To surf is to stand up, to ride or die, no VALs allowed. Criminals are surfers and surfers are criminals, and robbing banks is the natural and inevitable culmination of their existence on the margins, their rejection of gainful employment, their scorn for savings and loan.