Michael Haneke: The Prognosticator

By Catherine Wheatley

Time of the Wolf, dir. Michael Haneke, 2003

The Prognosticator

A prime example of Michael Haneke’s prescient filmmaking, Time of the Wolf eerily foreshadows the pandemic

By Catherine Wheatley

September 1, 2023

When news trickled down to us that Boris Johnson’s government was about to announce a national lockdown, my husband and I packed up our supply of toilet roll and whatever tinned goods we had in the house, loaded our children into the car and left London for my mother’s home in a rural area of Northern England. Before departing, I emptied our safe and made sure we had our passports. I was worried the house might be looted while we were gone. My husband rolled his eyes and told me I was being hysterical, but I could not shake the uncanny sensation that I’d been here before. And in a way I had. What we were doing was an almost exact replication of the opening scenes of Time of the Wolf (Le temps du loup).

In years to come, when future cinephiles look back on Michael Haneke’s films, they might wonder why we didn’t pay more attention to his warnings. Caché (2005) cautioned of the dangers of believing what we see on television long before the invention of deepfakes; 2000’s Code Unknown examined the consequences of turning our backs on refugees. Across all his work Haneke examines the legacies of postcolonialism, isolationism and capitalism. Time of the Wolf is arguably the most prescient of his works, a film that upon release was critiqued for being too mysterious about the catastrophe setting its narrative in motion but that today looks all too familiar.

Haneke’s 2003 postapocalyptic drama (or perhaps it is pre-apocalyptic, since the film takes its title from Völuspá, an Old Norse poem which describes the time before the Ragnarök) begins when a visibly middle-class family of four—Anne (Isabelle Huppert), Georges (Daniel Duval), and their two children, Eva (Anaïs Demoustier) and Ben (Lucas Biscombe)—pull up to a pretty log cabin in the middle of the woods. They are fleeing to their weekend home from an unnamed city, where something unspeakably dreadful is afoot. The locals are scathing: “You really don’t know the situation here?” one scoffs, before admonishing, “You should have stayed in the city.” Certainly the city-dwellers swiftly have cause to regret their decision, as they discover their home is already occupied by a family of squatters reluctant to cede territory, despite Georges’s admonition that the cabin is “private property.”

From left: Caché, dir. Michael Haneke, 2005; Code Unknown, dir. Michael Haneke, 2000

Time of the Wolf is one of several 21st-century artworks that seem to predict Western responses to the global pandemic, sitting alongside novels such as Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven (2014), Ling Ma’s Severance (2018), Don DeLillo’s The Silence (2020), and Rumaan Alam’s Leave the World Behind (2020). Unlike more classically inclined disaster fiction—Jordan Peele’s Us, HBO’s The Last of Us, the Walking Dead franchise—there are no zombies here, no monsters to be fought beyond our own selfish impulses. The common denominator in all these works is that the perceived threat centers around ownership, and in particular, the home. Lives are at stake, but so are livelihoods and living quarters. Alam’s novel begins, just as Haneke’s film does, with the arrival of the owners to their second home and a polite struggle over proprietorial rights. To paraphrase one of Alam’s characters, what’s happening might be the end of the world, but it’s also a market event.

What happened when the great disaster struck in 2020? We went shopping. At first it was for face masks and hand sanitizer, then ring lights for Zoom calls and printers for homeschooling. We bought pizza ovens so we could pretend we were at a restaurant, and patio heaters to keep us warm. We bought home gym equipment to work off the pizzas. The Amazon delivery people wore a path to our doors.

It’s this logic of capitalism, that we can be saved by our stuff, that underpins the opening moments of Time of the Wolf. When Georges realizes that the intruders have the upper hand, his first response is to buy them off: “We have supplies,” he tells them, inadvertently showing his hand. What he fails to realize is that in the climate of emergency, the old rules of propriety and property no longer apply. This is the Wild West.

From left: Us, 2019; The Last of Us, 2023; The Walking Dead, 2010

Forced out of their home, the family makes its way to an abandoned train station, where a makeshift community of sorts has sprung up. Here the fetishization of property persists, but the value of items has changed. What use is a mobile without a charger? Without electricity? Anne is reassured that her bike is a big-ticket commodity, but the horseback mercenary selling water gestures at his steed and laughs in her face. For so many of the characters, the catastrophe has already taken place: Without realizing it, they’ve come to rely on wrong things. As in prison, what sells is food, drink, cigarettes and sex. In this state of emergency, we revert to basics. The hottest commodities (if you’ll pardon the pun) are lighters—all the better to start a fire.

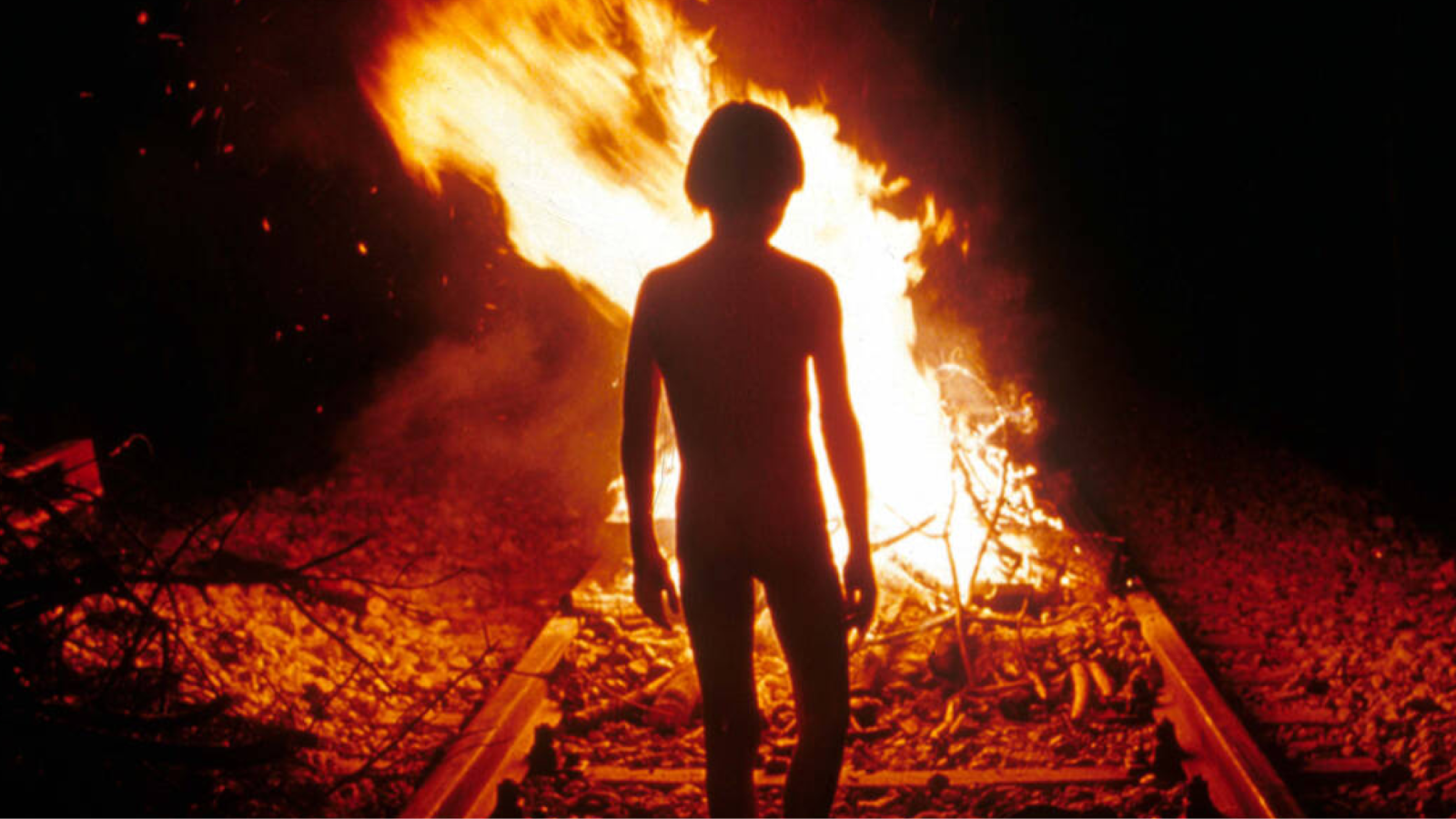

Haneke focuses on the signs and symptoms rather than the cause. A disaster movie without a disaster, Time of the Wolf is remarkable among the director’s films as being the one of only two that he’s made without featuring diegetic TV footage. How media stultifies our ability to empathize with others and engage with politics is a running theme for Haneke. For example, 1992’s Benny’s Video sees a young teen recording himself killing a schoolmate “to see what it’s like,” while 2017’s Happy End contrasts security camera footage of a horrendous disaster on a construction site with the callous proprietor’s denial of its gravity. We’ve stopped paying attention, Haneke tells us. And yet it’s precisely the absence of information that makes Time of the Wolf so disturbing. One character has a radio we’re not allowed to hear; we discover headlines only when relayed by its owner. Occasionally we glean snippets of information: There’s no electricity or running water; the rivers have been contaminated, as have the cattle; supplies are being rationed; and the country is out of petrol. For the most part, we, like the characters, are both figuratively and literally in the dark. When night falls for Anne and the others we must peer into the shadows like they do, eyes straining to make out the figures fumbling about.

From left: Benny's Video, dir. Michael Haneke, 1992; Happy End, dir. Michael Haneke, 2017

Make no mistake, Time of the Wolf is a difficult watch. It’s also at times terribly, deliberately boring. Of course it is—because contrary to what Hollywood so often tells us, disasters are boring. There’s no sense of urgency, no countdown clock. The meteor isn’t heading for Earth. In more conventional apocalyptic fiction, the driving effect is suspense. We anticipate the arrival of the scientist with explanations and solutions, the dramatic spectacle of disaster narrowly averted. In Time of the Wolf, there are no clocks. No one knows what day it is or how long they’ve been waiting for the nameless thing that might shift their circumstances for better or worse. Anne can’t barter her watch because no one cares what time it is.

I cringe to write it now, but when we made our midnight flight three years ago, I packed a party dress and a swimsuit. I probably was being hysterical, I told myself. It would all be over soon. After all, life isn’t like the movies. And sure enough, in 2020, the worst did not befall us. We used up our tinned goods and ordered fresh supplies from Whole Foods. I went swimming in a nice clean river and wore my party dress to eat pizza in the garden on my birthday. The cinemas shut but our TVs stayed on, and night after night we watched the prime minister address the nation before we went outside to clap for the National Health Service. We called the men and women who put on protective clothing and worked ceaselessly to keep us alive “heroes.” We made celebrities of them, turned them into movie stars.

It wasn’t long before we were idly scrolling past the latest death tolls on our phones. We were lucky. The pandemic took us to the precipice of a disaster that Haneke makes manifest. For many, on a personal level, the pandemic was a disaster. Others now talk of it nostalgically. Remember how peaceful it was? Remember all that quality time we had with the children? Remember when we bought a puppy? Remember Time of the Wolf? I’m not sure enough of us do. We forget it at our peril.