The Road to Nowhere

By Willing Davidson

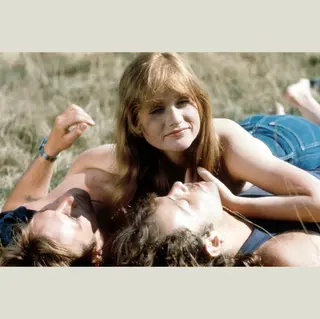

Going Places, dir. Bertand Blier, 1974

The Road to Nowhere

Going Places is a problematic film about bawdy criminality. It also collides with unnerving truths

By Willing Davidson

February 23, 2024

Going Places (Les valseuses) is the movie to watch if you think that you’ve come to the end of the notion of romantic triangles. Maybe you think you’ve transcended Jules et Jim and no longer mediate your relationships through the specter of a (visible or invisible) third person. Going Places reminds you: Life is triangles. Its story, two young men plus one person at a time, is anarchic, corrective and also a picture of a cracked-open world—the early ’70s, France, the slow, uncertain ebb of the purposeful ’60s.

The plot is a cascade of criminal events, as Jean-Claude and Pierrot (Gérard Depardieu and Patrick Dewaere) reject the proprieties of bourgeois France for a life of petty thievery, joyrides and sexual conquest. Though their first heist is a shopping cart, they also steal multiple Citroëns. (Two of them are the still-coveted DS, with hydropneumatic suspension. You pull the lever and the car’s body starts to levitate. Another is a 2CV, a symbol of postwar French resurgence that Jean-Claude and Pierrot treat with contempt, slicing open the canvas top to get in.) It’s a movie that’s on the run, and the scenery moves frequently, often alternating between the already decaying new banlieues and the tall poplars and Renoir canals, each infecting the other in the way that even in the most wistful Rohmer movie the timeless valley has the stack of a nuclear plant in the background. These quick juxtapositions are often quite beautiful; more important, they’re effective, bringing reality to the postcard view.

The director, Bertrand Blier, the son of a famous French actor, knew Depardieu but initially resisted casting him. (Blier wrote the novel before directing the film—you don’t see that too much anymore. Now even Tarantino has to do it in reverse.) Blier’s father, who had been in a play with Depardieu, asked Blier, “What’s the point of holding a casting call since you know you’re going to pick Depardieu?” Depardieu, eager for the role, came to visit Blier every day, each time as a different character—a bourgeois, a member of a motorcycle gang, an old man. Success.

In the film Depardieu is a menace—a wounded, thick baby menace. You want to take care of him, save his soon-to-decay body, make his pointy Mephistophelian chin slowly curve into his cheek forever. Depardieu looks best in flared pants. Beside him Dewaere, as Pierrot, seems more period, more time-bound. He’s a minor-key d’Artagnan going sour. A wispy mustache and a resentful air of subordination, and it’s clear that Jean-Claude is in charge, just as Depardieu is. He’s the one with the ideas—hide out in a deserted beach town, drive all night in the hope of picking up a woman upon release from prison—while Pierrot’s only scheme is to sabotage a car and give it back to the owner, believing that it will kill him. (The owner sells it.) Put together, Jean-Claude and Pierrot are an alienated, less optimistic Wayne and Garth. What do these two fools want? They want women, primarily, or the set of activities and fantasies that, in this time and sexual orientation, can be made to revolve around women. What they’ll do for them, what they’ll do to them. They chase women—chase them as they flee down deserted streets. They unzip and rezip their flies, hump furniture and each other, and chase some more. And when they catch them, they want to pleasure them.

Gérard Depardieu and Patrick Dewaere with Isabelle Huppert (left) and Miou-Miou (right) in Going Places

This is odd. But the ’70s were peak orgasm, the political turned bodily, salvation in a spasm. It’s tempting to think that orgasm ideology came from the U.S., like Coke and woke, but presumably France had its own Shere Hite, riding the fumes of Kinsey, preaching jouissance. Easy to make fun of, but it’s good to come. People should do it more often. Indeed, a major subplot of Going Places involves the efforts of our heroes to give an orgasm to Marie-Ange (Miou-Miou), a young woman they’ve abducted. They try all the positions, all the combinations, but what they do not try is not raping her. What gets her off, finally, are the ministrations of a young man, a virgin just out of prison, who lies there, wanting nothing, giving nothing.

Marie-Ange, in turn, plays a crucial role in taking a 16-year-old girl from her family (along with their Citroën DS) and persuading her to let the boys deflower her. Her name is Jacqueline, and she’s played by Isabelle Huppert. You kind of wonder what the atmosphere on set was like.

It’s hard to watch any film without the present impinging on the past. There is now a long list of credible sexual-assault allegations against Depardieu (he has not been convicted of any of them and maintains his innocence). The French culture minister recently said that she was considering revoking Depardieu’s Légion d’honneur. It happens—at least it happened to Bashar al-Assad and Lance Armstrong. Still, these things play differently in France. An open letter went around accusing the media and the public of “lynching” Depardieu, of ignoring the presumption of innocence. Blier signed. Huppert did not. Many of the more critical articles about Depardieu are paired with a wire photo of him looming over Huppert, in a mock pass, as she acts as if it’s that old French gallant, the cocksman on parade. The photo was taken at Cannes in 2015, where they were promoting Valley of Love (in which a divorced couple reunites in Death Valley, California, with the hope of manifesting their dead son). Wikipedia: “While Isabelle has stayed petite and attractive, she is shocked to see that Gérard is in poor health and enormous.” Behind them dozens of cameramen—only men in the frame—point lenses.

“The film applauds Jean-Claude and Pierrot’s revolt against society, but it can’t seem to understand that this anarchy is available only to men.”

Coercion and vitality underpin Going Places. All Jean-Claude and Pierrot’s interactions involve coercion of some kind, and the unseen element is the coercion that they feel they’re subject to from society, which they experience as a threat to their vitality. In the abduction of Marie-Ange, her boss at a beauty salon—a representative of new, suburban France—shoots Pierrot in the groin. Will he ever fuck again? Not, initially, when he frets over trying it on with Marie-Ange. Nor when he and Jean-Claude, on an almost empty train, find a woman breastfeeding her child and coerce her into breastfeeding Pierrot. It’s played for laughs; it’s played for terror. But the terror goes both ways: When the woman gets off the train, unharmed, and greets her pencil-necked geek of a husband with real joy, Pierrot and Jean-Claude are left inside the train, outside the society that they don’t know how to confront. They’re rebels without a concept. “When people leave us alone, the simple things make us happy,” Jean-Claude says, an obvious irony, since they’re about to steal bicycles before upgrading to yet another car. But he’s pointing to something real: In the society that’s rising around them, where morals are not undermined but reinforced by new forms of consumer goods and central planning, people like them can’t be left alone. Stealing a car is just what you do when no one will pick up hitchhikers anymore. There’s security at the giant supermarket, cops on motorcycles at the country inn, quasi-feminists at the bowling alley. There’s no glory to be won, no place for these bawdy medieval characters to land.

Then comes Jeanne Moreau, as the released convict they pick up outside the prison, tragedy and dignity to the rescue. They treat her to a grand lunch, imploring her to eat slowly, and when inevitably they have sex with her, she tells them to go slowly, too. And they do. It’s a kind of redemption for the boys, a sentimental education they pay for dearly, though it’s not as costly for them as it is for their teacher. She kicks off the second half of the movie, which involves, for the first time, emotional consequences for Jean-Claude and Pierrot and even for Marie-Ange, whose own awakening comes in the form, naturally, of an orgasm.

Proximities in Going Places

It can feel icky to watch Going Places. Of course you connect Jean-Claude’s predations to Depardieu’s reputation for alleged sexual crimes. But I know what to do with the art of monstrous men, for better or for worse. Here it’s the art, not the man, that makes me hesitate. The film applauds Jean-Claude and Pierrot’s revolt against society, but it can’t seem to understand that this anarchy is available only to men. That the reason the women walk so carefully—instead of skipping, leaping, running, as Jean-Claude and Pierrot do—is not because they lack some essential spirit but because they are in physical danger from men like them. They are on guard not because of moral repression but because being inconspicuous is their best chance at surviving the world that Jean-Claude and Pierrot are making for themselves. The film to some degree admires its protagonists’ assaults and wonders why women can’t keep up. It must be their parents, de Gaulle, corsets. Yet it doesn’t take critical theory to understand that the camera that follows a nameless woman walking in fear down an empty street is held by a man.