We Are All Animals

By Wendy Ide

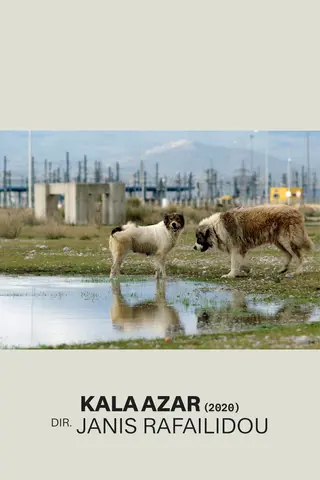

Kala azar, dir. Janis Rafa, 2020

We Are All Animals

With palpably feral filmmaking, Janis Rafa’s Kala azar dethrones human supremacy in the natural order

By Wendy Ide

January 5, 2024

Many films tell a story from an animal’s point of view. Jerzy Skolimowski’s Oscar-nominated EO is a recent example, with the director drawing inspiration from Robert Bresson’s classic Au hasard Balthazar (1966). Documentary has a plethora of examples: Andrea Arnold’s brutally visceral hoof-level lens in Cow, Victor Kossakovsky’s artfully empathetic pig epic, Gunda, or the giddy rush of the “dog cam” segments in Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw’s The Truffle Hunters, wherein the camera views the world through the eyes of its animal subjects. For children, Disney built a mammoth empire out of its distinctly cuddly approach to the animal kingdom.

From left: Kala azar; Au hasard Bathazar, dir. Robert Bresson, 1966

Greek visual artist Janis Rafailidou (who adopts the abbreviated moniker Janis Rafa for her film work) took a different tack with her debut feature film, Kala azar (2020). Rather than foreground a particular creature, the film, like her unnerving ethereal gallery videos and installations (one of which showcased at the 59th Venice Biennale, in 2022), embraces an animalistic means of filmmaking and storytelling. Rafa is more interested in finding the animal at the heart of the human characters than anthropomorphizing the beasts for our own comfort.

Kala azar tells the story of an unnamed woman (Penelope Tsilika) in her early thirties and a slightly older man (Dimitris Lalos) living a bohemian, peripatetic existence. The pair eat, sleep and couple in a battered van situated on the sprawling outskirts of an unnamed southern European city, a liminal space between city and country wherein animals roam in détente with humanity. Rafa deliberately doesn’t tell us much about the human characters—we know that they have rejected the conventions of normal society; like the animals, they just are.

They work for a pet-cremation service, collecting the bodies of beloved creatures and returning little urns full of ashes to grieving owners. But while the bereaved cherish the connection with their own special animal, the couple reject the idea that some creatures are more important than others. They care just as fiercely for the stray dogs wandering the wastelands or the roadkill lining the highways. As the film unfolds we see that, for this couple, grieving every animal casualty of the human world is an intolerable burden, one that increasingly distances the woman (in particular) and the man (to a lesser extent) from their fellow homo sapiens.

Adopting a visual palette of grubby earth tones, with shades reminiscent of sweat, blood and piss, Rafa creates a novel cinematic experience in which we can almost smell the fetid scene. The characters are unselfconscious about nudity, about the workings of the body, about scabs and dirt. Their blithe disregard for basic hygiene helps to break the fourth wall. This emphasis on the primal extends to the textured, organic soundscape by sound recordist Nikolas Konstantinou. By deprioritizing the spoken word as a means of communication, the director brings out an instinctual, animalistic performance style, encouraging a feral impulsiveness in the actors to fill the dialogue void. This can be seen in the chic parlor of a wealthy elderly woman paying her last farewell to a favorite tropical fish. The couple, distracted by the sound of a dog locked in an adjacent room, are twitchy, anxious, and more in tune with the distress of the animal than the performative grief of the pensioner.

From left: The Truffle Hunters, dirs. Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw, 2020; EO, dir. Jerzy Skolimowski, 2022

This film, like several of Rafa’s video pieces, such as Father Gravedigger, Our Dead Dogs and The Last Burial, features the director’s father, Tassos Rafailidis, in a supporting role. Here he plays the woman’s father, with a pivotal turn in an extraordinary scene involving a brass band at a poultry farm. The father bribes a worker at a chicken-processing plant to let him play an excerpt from Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations to the birds awaiting slaughter, combining absurdity and a sharp stab of pathos that’s in harmony with the story’s themes. Rafa has said that casting her father is connected to her childhood memories of the stray dogs her parents took in and “this image of my father as the gravedigger when they died.” Her quest is to explore how animals and humans coexist and the act of “noticing the unnoticeable”—recognizing those unfortunate creatures humans deem unimportant.

Boundaries are blurred in the photography as well. Cinematographer Thodoros Mihopoulos doesn’t distinguish between the bodies of animals and humans—he discovers both in the same way: in small textural details, bit by bit, refusing to capture the whole. We see the paws of an exploring dog rather than the whole animal; the limbs of the couple intertwined and indistinguishable from one another. The result is a kind of visual abstraction matched by the disconnect that the camera brings to the storytelling. Doglike, the lens follows the scent of what interests it, often leaving the human element of the picture to exist outside the frame. Rafa is attempting to reframe what is important in cinema, as she conveyed at the time of the film’s debut: “We are so immersed in our egos, so convinced we are at the center of everything, when in fact there are individualities extending far beyond us.”

That’s not to suggest humans are insignificant in the world of Kala azar. The title derives from an infectious disease, a potentially fatal epidemic also known as visceral leishmaniasis, or black fever, which is transmitted by insect vectors that can infect dogs or people. But the symbolism within the film, with its images of swaggering hunters, of discarded animal corpses, of casual cruelty, is clear: The main sickness that ails this blighted world is humanity. Much of Rafa’s work hints at environmental and social collapse. Uniquely, what distinguishes Rafa’s approach is her refusal to manipulate audience members into projecting themselves onto the creatures on screen. Even the boldest and most creative films exploring the world from the animal’s vantage point are ultimately dependent on the human perspective. Arnold’s remarkable Cow, for example, relies on our understanding of motherhood; EO engages with our moral stance on labor abuses. In Kala azar, however, we navigate the film on an instinctual level. We may enter the cinema as humans, but Rafa encourages us to leave it having connected with the beast within.