Wicked Funny

By Gérald Duchaussoy

The Girl Who Knew Too Much (aka The Evil Eye), dir. Mario Bava, 1963

wicked funny

Was the Italian giallo horror master Mario Bava laughing behind the lens?

By Gérald Duchaussoy

February 20, 2024

Known for his foundational contributions to the horror genre, cult Italian director Mario Bava was also a notorious joker. His love of humor is attested by his son, Lamberto (who served as his assistant director from 1965 onward and worked as the co-director of his last film, the 1979 TV movie La Venere d’Ille), as well as by actors who starred in his considerable oeuvre. It’s even the theme of one of Bava’s least remembered films, his slapstick spoof on spy thrillers, 1966’s Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs, which he was reluctant to direct but which shows his natural talent for eliciting laughs. Bava, of course, is most famous for helping to invent the influential mid-century Italian genre of giallo, a highly stylized fusion of thriller and gore that often involves a masked killer in a raincoat executing a series of artfully sadistic murders in increasingly sensational fashion. In Bava’s giallo productions, psychotic murderers wield knives as skillfully and efficiently as the director does his camera, with plenty of icky details filling the screen. But beneath Bava’s darker films, does there lurk wit and humor?

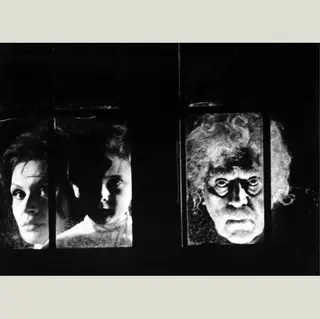

Black Sunday, dir. Mario Bava, 1960

Consider the salacious reference to marijuana that makes an early appearance in Bava’s mystery The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963), where an American arrives in Rome only to witness a terrible murder. The mind-twisting plot turns quickly make the audience feel like they too have smoked marijuana. Note how Bava lights the arrival of a police officer with a terrifying shadow (a dramatic technique inherited from silent films) to turn the idea of safety and justice on its head. Soon he shows a priest picking up a pack of dropped cigarettes in a gesture that resembles petty theft. These insistent details lead us to question how much of the heroine’s paranoid experience is happening inside her head. Or appreciate the mise en abyme in his classic 1963 horror anthology, Black Sabbath. At the tail end of the film, the anthology’s famous narrator, Boris Karloff, laughs as he appears to be galloping at high speed through a woodland. The camera pans back to show Bava’s crew waving fake tree branches to simulate the actor in flight. The horse turns out to be a mechanical prop, and Bava and his assistants playfully circle the cameraman. This scene at the end of a horror film makes one wonder if this overt prankster attitude hints at the director’s relationship to his sinister material.

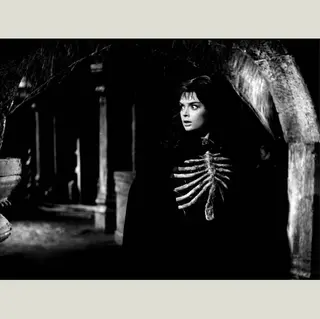

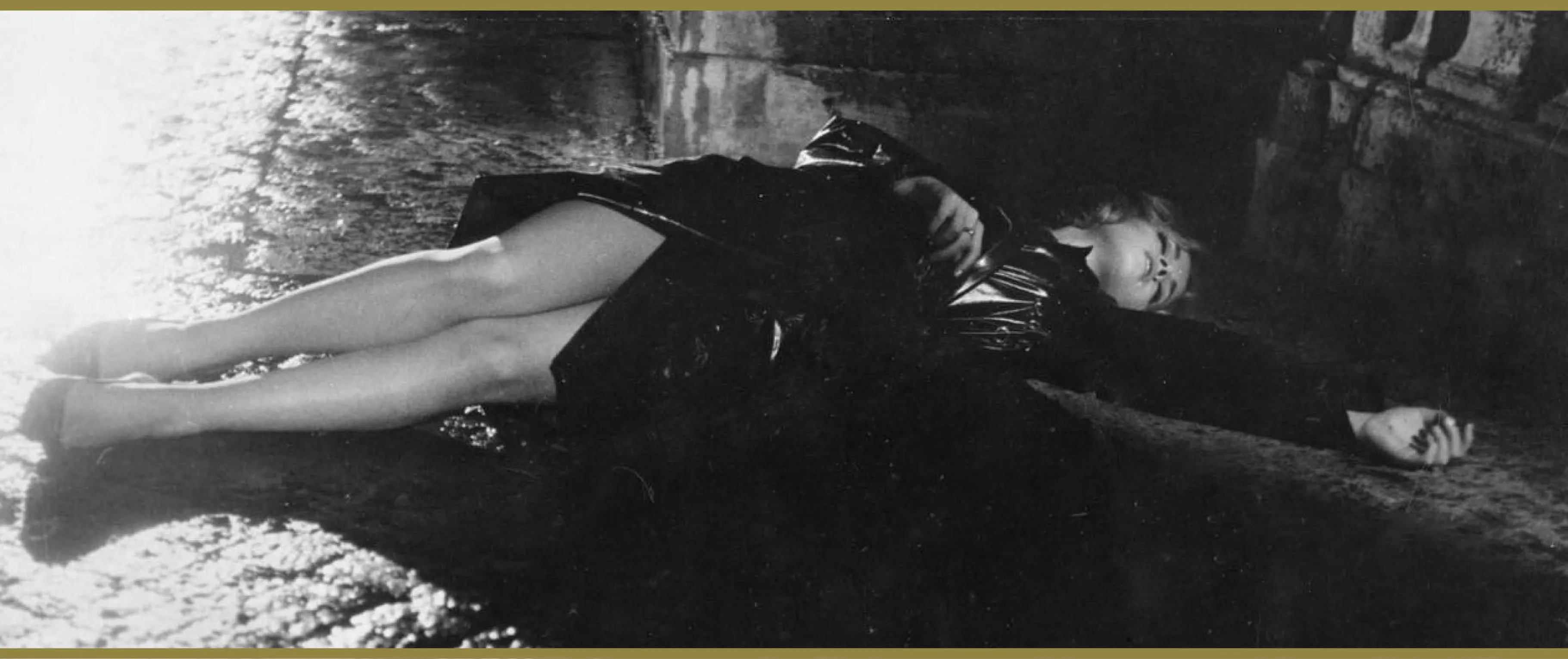

The notion of Bava as a humorist is put to the test in viewing his gothic horror masterpiece, Black Sunday (1960), which could hardly be classified as a comedy. A loose adaptation of Nikolay Gogol’s short story “Viy,” the film tracks a murdered vampiric witch who comes back to life in nineteenth-century Moldavia, two centuries after her execution, to wreak havoc on a nearby village. The atmosphere of the moody black-and-white film is suffused with dread, and its special effects were considered extreme for its day—the gore includes a full shot of a bloody bones-and-flesh rib cage inside an open chest, a mask studded with nails hammered onto a woman’s face, and the burning of two live bodies. Although Bava treats the anxiety of the film seriously, it’s hard to deny its campiness. (Of course, most horror cinema verges on camp with its reliance on lurid theatricality and extreme emotion.) In one sequence of the film, a protagonist fights off a giant fake bat with a cane, the prop’s wires clearly visible despite the accomplished lighting. Yes, it’s certainly camp. But is it funny?

From left: Black Sabbath, dir. Mario Bava, 1963; night wanderings in Black Sunday

Black Sunday marks Bava’s debut as a credited director (in the 1930s, he worked with his father in special effects before transitioning to cinematography and eventually spearheading a number of horror films in the 1950s as an uncredited director). To put his stamp on Black Sunday, Bava seemed intent on pushing the boundaries of what horror could achieve, and in this dark and wicked spectacle there are certain playful moments that read as the director’s inside jokes with his audience. They may not be laugh-out-loud funny, but they do reveal a director trying to have a good time with his art form. In a clever meta-gesture far ahead of its time, Bava loops one dramatic climax in the plot, when a grim executioner puts a mask over the heroine’s face, back to the opening credits, where the camera zooms in on a bronze mask as the name of the lead actress, Barbara Steele, flashes across the screen. He seems to be playing a subtle game of I told you so with his audience, revealing her horrible fate at the start of the film. It’s not the only evidence of Bava’s games. Time and again, the plot’s central action is obscured by fog and foliage, as if Bava is playing peekaboo with our voyeuristic tendencies, offering scenes of extreme horror and threatening to snatch those sights away—before, of course, rewarding us by delivering the gruesome goods.

Black Sunday’s formal beauty helps provide much of the film’s tension, thanks in part to the fact that it was filmed on black-and-white DuPont film. Renowned for the richness of its silver salts, this filmstock was produced in Italy at the time. DuPont de Nemours, Kodak’s main competitor, was its sole manufacturer due to a deal struck with Pathé to limit its production and export. The effects of this rarefied celluloid help give the film its lush quality, capturing the eeriness of each scene’s mistiness and murk. Given the serious, artful atmosphere, it’s that much more of a surprise to encounter a character as comical as the bumbling coach driver at the beginning of the film—this parodic, drunken buffoon feels straight out of a bad Western. The classic comic figure immediately undercuts our expectations of what kind of film Black Sunday is going to be. Bava’s films are masterpieces of camerawork and jump cuts, and with this elevated film stock, he makes surprisingly whimsical use of it.

Letícia Román in The Girl Who Knew Too Much (aka The Evil Eye)

In this early scene, the camera watches the horse-drawn carriage disappear into the horizon before panning 30 degrees to reveal a massive tree trunk covered in jet-black leaves. The screen goes black—perhaps the deepest black ever captured in a film at the time. The next shot is a pitch black entrance of a cave, with only the branches surrounding it visible, and a forward tracking shot literally propels us inside this void. Black, which for French philosopher Gaston Bachelard is ‘‘the mother of all colors,’’ becomes total. The camera pans the cobweb-covered crypt and pauses on the witch’s tomb. When Dr. Kruvajan (Andrea Checchi) removes her mask, the camera reveals a female face covered with lacerations and pustules, whose eyes are empty black cavities. Soon, a close-up of boiling black matter rising up from her eye holes amid strands of her tangled hair. No doubt precisely what viewers expected when they bought their movie ticket. But a sudden cut takes us into an extremely different scene: Katia Vajda (Steele) is happily playing the piano in a castle. The film’s pacing goes from allegretto to affannato in an anxious, breathless rhythm. A music lover, Bava uses rhythm to poke fun at our fears, spooking us by the abrupt change in tone and pacing (such extreme juxtapositions have since become a horror-film standard to jolt the audience out of complacency). It’s also Bava’s mischievous directing style that continually challenges our notion of Kruvajan, whose warm, smiling face can turn frightening and impassive, lit with bleak whiteness. In one scene midway through the film, Kruvajan approaches the witch and kisses her on the lips. In this kiss of eternal death, the two figures visually merge into one body with two heads as their shadowy faces blend together in an indistinguishable unity. It’s a fusion of love and death—the cliché of Eros and Thanatos transcended by dark humor.

“Although Bava treats the anxiety of the film seriously, it’s hard to deny its campiness.”

The contrast between the darkness of the story and the lightness of the camera movements was perfectly achieved thanks to camera operator Ubaldo Terzano and Bava himself as cinematographer. A master of lenses, filters and special effects, Bava has a blast with cinematic form and sets technical challenges for himself throughout Black Sunday: filming fire; avoiding reflections while filling the set with windows, mirrors and glass; using paintings to illustrate angst. The female nude portrait that grants secret access to the crypt—a frisky image meant to satisfy the needs of the young male movie audience—is a cliché that Bava employs as a tease, despite his reputation as a prude. Today, it’s surprising how much of Black Sunday can be read as a commentary on the aging of women and their punishment for exercising their sexuality. By explicitly showing the violence that young women experience, ultimately the profound message of the film isn’t funny at all. To this point, he makes use of lighting to alter Barbara Steele’s movie-star features and transform her into a wizened witch devoured by flames—an image that is truly scary. Still, of all of his tricks, technical and tonal, it’s the wit, irony and jokes, sprinkled throughout such a seminal horror film—as well as much of his output—that keeps it alive as a horror for the ages.

From left: Barabara Steele in Black Sunday; Boris Karloff in Black Sabbath