Wimself Pt. I

By Josh Siegel

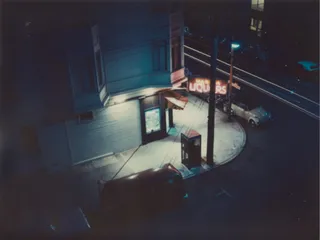

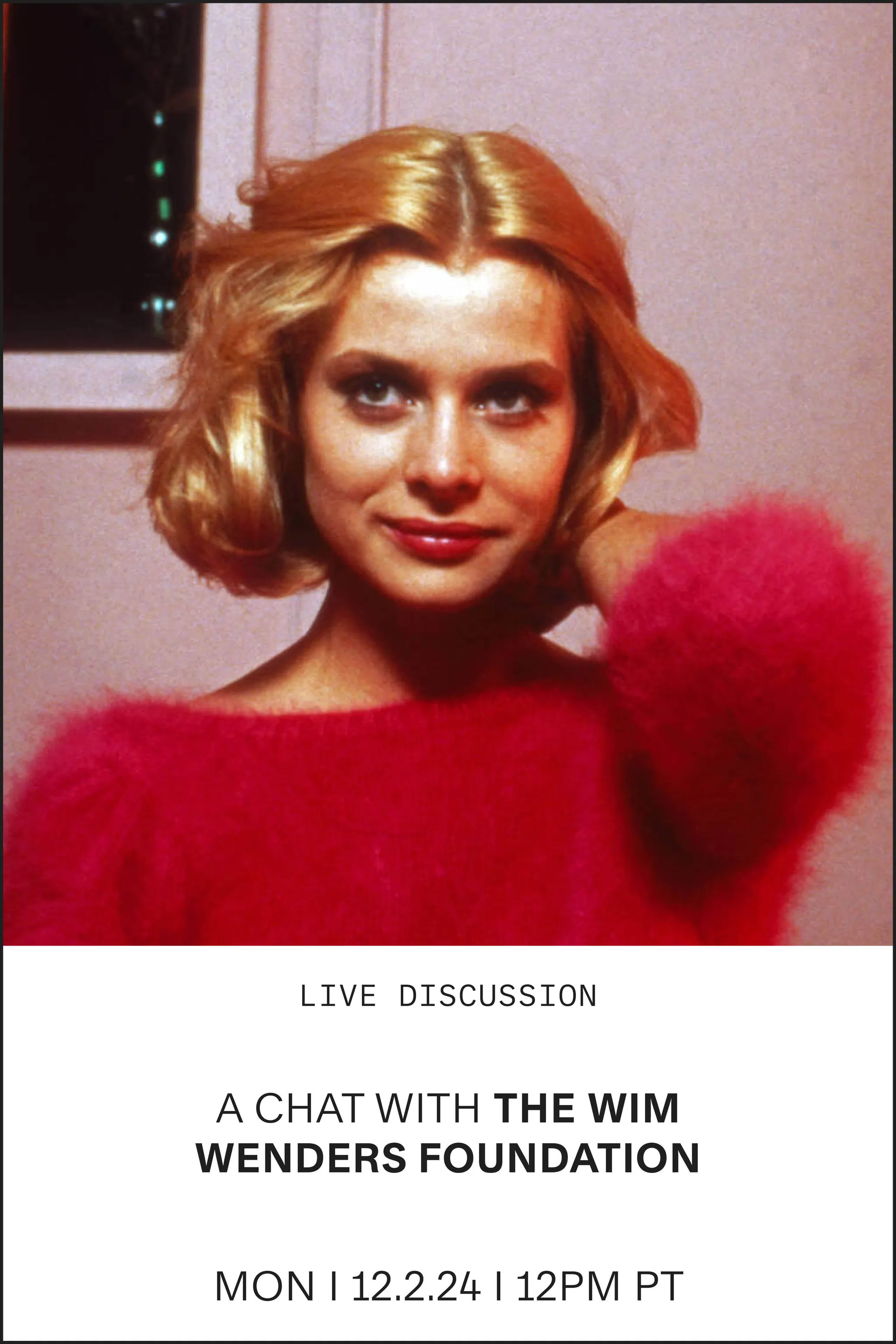

Liquor Store, San Francisco, 1973

WIMSELF pt. I

By Josh Siegel

Photography by Wim Wenders

A candid and freewheeling conversation in four parts with Wim Wenders, the poet laureate of New German Cinema

December 2, 2024

Here’s a strange paradox to chew on: Filmmakers who excel at fiction rarely excel at documentary. Here’s another: Good filmmakers rarely make good still photographers. Wim Wenders is the exception to these rules—and many more. The 79-year-old German director has made 36 feature films since his start in 1967 with Schauplätze, and in that time he’s also produced music videos, shorts, television programs, a number of photo books ranging from portraits to landscapes to behind-the-scenes anthologies, and well beyond. Should there be any doubt about his wide-ranging bona fides, consider his most recent film work from 2023: Anselm, his portrait of a contemporary German artist told through cutting-edge 3D technologies; and Perfect Days, his haiku-like homage to the gently comical family dramas of Yasujirō Ozu.

It’s a mark of Wim’s generosity, and curiosity, that he took part in onstage conversations following every one of his screenings during the 2015 MoMA retrospective I co-organized, which is where we solidified our friendship. And so, while passing through New York City en route to Hollywood, Wim gamely took up my invitation to have a freewheeling discussion about “20 Things” that have preoccupied him of late, from ideas of home and language to the pleasures of Dashiell Hammett and Donald Duck. Like his movies, or a great jam session, or a great road trip, a conversation with Wim is at once structured—he wrote out the talking points in advance of our meeting—and utterly improvisational. Our spontaneous detours suggested riches of thought and feeling, and I was reminded of the epigraph to Wim’s book of essays, The Act of Seeing, a quote from 1920 by the painter Paul Klee: “The artist strives to express the essential character of the accidental.” Wim and I spoke for five hours. The conversation easily could have gone on for five more.

ADDICTION

![]()

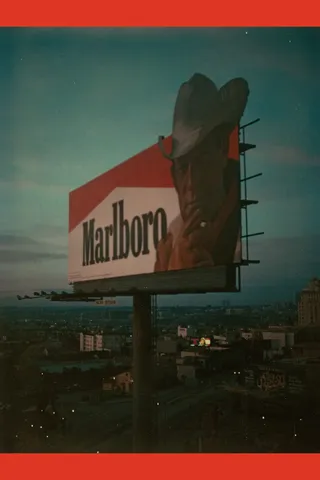

Dead Man Smoking, Los Angeles, 1977

![]()

AA Center, Paris, Texas, 2001

Wim Wenders: When I smoked, I smoked a lot. In the end, it was five packs, 120 Marlboros a day, during Faraway, So Close! [1993]—120 was my limit. The prop man wasn’t allowed to give me another pack. Any cigarette after that, I had to bum off other team members.

Josh Siegel: Six packs a day? That was very abstemious of you.

I had to stop smoking because I couldn’t walk up the stairs anymore without pausing. And when I then squeezed out my last one, I really meant it when I said, “This is the last cigarette of my life!” I never touched one more.

Once I got addicted to gambling. When I was living in San Francisco, preparing Hammett [1982], I once drove to Reno and just for fun sat down at a poker table. Played all night. Then every weekend, then for the entire next month. A true addiction. I dreamt about Texas Hold’em. The addiction ended beautifully: One night it was going well and I was in the chips. There was one empty seat at the table. These little old ladies came along and asked everyone at the table, “Could we sit together on one chair and take part in the game?” They giggled. We were all tired, but since the ladies were so sweet we invited them and explained the rules to them. They played and lost for a while, until they won a hand, a big hand actually. As they clapped and cheered, the faces around the table got darker. The first man left, excusing himself. The ladies now had two seats. And then they cleaned up. One guy after another lost all his chips. I was the last one left. I couldn’t believe how they did it, how I also lost everything. It was fascinating.

You got hustled.

“What an experience!” I thought when I finally got up and went to the toilet. The croupier who had dealt for the last two hours peed beside me and whispered, “They come once a month.” I nodded. Of course. It ended my addiction. I never played poker again. To be so abused, to realize these old girls with their blue wigs either had a scam or were so much better, it showed that I was a nobody in poker.

What other addictions did you have?

Well, filmmaking is an addiction. It became an addiction very quickly. I’m addicted to the process. My favorite parts are the first—location-hunting and looking for a place to tell a story in—and the last, editing. I drag out the editing as long as possible because I like it so much. I like the possibilities: Cut a little shorter here, leave it a little longer there, try it the other way round. The possibilities of editing are endless until you know: This is it, this is the best of all options, now you made it as poignant as the material allows for. It is inside the material that you find the film. It shows you how it wants to be told.

How did the idea of possibility in the editing process change from celluloid to digital?

It changed the entire ball game! On the analog editing table, I could edit myself. In fact, I edited a couple of my films alone. I liked the craft of it, the splicing, the pasting together, putting the trims back. You have to be a very orderly person, because if you’re not, soon it’s a mess and not fun anymore. Peter Przygodda, my editor for 40 years, of the entire analog age into the digital realm, knew me well. He knew instantly in the morning if I had continued editing myself at night. He grumpily looked at it, then would shake his head and would change back most of my cuts. But some he nodded [at], as if in amazement, and left them. With celluloid there was a limited amount of film. Sometimes the budget itself would dictate the amount of film stock you had at your disposal. That would force you to rehearse longer. In digital you shoot the rehearsals and you can shoot endlessly, which doesn’t mean that you have a better movie. In my own experience, all digital edits took twice as long as any analog edit before.

Limitless choice doesn’t lead to clear decision-making.

On the contrary. With Peter we were still shooting and editing Wings of Desire [1987] in February, March even, yet we were ready for Cannes a couple months later, even if we still had complicated sound work to do. In the digital world, Anselm took three years to edit, The Soul of a Man [2003] and Buena Vista Social Club [1999] took two. Because in documentary-editing you have to find the structure of the thing. With fiction you have a structure already. Basically the editing process is finding out which film you made, and that involves being informed by the material. Thankfully I have the knowledge from the shoot and a thorough memory of all my shots. Some young editors, they don’t even look at all the shots. They look at the last one, thinking that must have been the best one, and edit right away. They’re used to editing commercials and music videos. I can’t edit with these people who start editing a scene without having seen each and every take. Even the outtakes! You have to know what’s in the outtakes.

When Fred Wiseman makes films, he uses what he jokingly calls a Michelin star system: He watches the hundreds of hours he’s filmed and then ranks each shot in a notebook. The ones he’s rated two and three stars he watches over and over again—perhaps this is a good kind of obsession—until they become like muscle memory, so that he can find some form for the film in the editing process. That’s how patience and implicit knowledge of the material are essential to how he constructs a film. It sounds like you get frustrated with editors who don’t appreciate that approach.

No, they’re just in a rush to put some stuff together. Which drives me crazy. But it’s just as addictive to want to know each and every option.

After a Concert by Die Toten Hosen at the Westfalen Stadium, Dortmund, 2001

“I would slip a vinyl record into my Columbo raincoat, which had a self-made pocket inside where the LP would fit in neatly.”

Is it fitting for our topic of addiction that we start with drugs and end with running? You told me you were a runner.

Addiction goes into healthy directions, too! I was a very addictive runner. I couldn’t live without running my hour a day at least. I also did marathons and cross-country. The longest stretch I had was in the Hollywood Hills, all the way from Beachwood Canyon to the observatory and back. I hated running in circles or on a treadmill. I like to run in nature. If I find a good path with options, I just dream of it from morning to evening. It was a hard blow in my life when the doctor said, “You have to stop running to save your back.”

Your back was shot? What replaced running? Work?

Yeah, I’m a confessed workaholic, and that is my greatest addiction, after all. I cannot stand still. I define vacation as: Finally, I can work in peace. I get itchy if I don’t have something to write or photographs to take or a film to work on.

There’s nothing more boring than a beach vacation.

I’ve done it for a maximum half-day in my life. I don’t even like to run on the beach. It’s not good for your feet, running on sand. But sitting in the sun—it’s hilarious people think of that as an ideal vacation. I’d rather clean toilets. [Laughs]

What about the addiction of stealing things? You once said you had this coat that enabled you to shoplift vinyl records. I too had a shoplifting habit when I was young.

That was a great passion rather than an addiction. I would slip a vinyl record into my Columbo raincoat, which had a self-made pocket inside where the LP would fit in neatly. Nobody thought you’d steal vinyl, anyway. Well, there were people who stole them from the sleeves, but that was stupid. You need the sleeve as much as the record!

Like many addictions, there’s something thrilling about stealing. Let’s be honest, it was the thrill of the chase as much as actually getting the vinyl record.

I don’t know about the thrill. I didn’t really like the thrill, but I needed the LPs. I never stole anything else but records, because that was the thing I needed most and I couldn’t afford it. I stopped before I was ever caught.

MDH behind the scenes, Los Angeles, 1999

Speaking of addiction, do you remember the very first image of your second short film, Same Player Shoots Again [1968]? It may even be one of the two surviving shots from your first short, Schauplätze, which you incorporated into this second film. It’s an image of a card dealer on television, panning over to liquor bottles on a table. There’s your gambling and your drinking in one of the very first images you ever took.

Amazing that you know that. Yes, it is what’s left over from that first film: the gambling table, but without a story. The telephone dangling in the empty booth was also from that. These were my leftovers. When I edited Same Player Shoots Again, my pinball movie, basically I had only one shot of the guy running with a machine gun, so I used these leftover shots from Schauplätze as a preamble. I had shot that lost film on reversal material, so there was no negative. I showed my only print until one day it was lost.

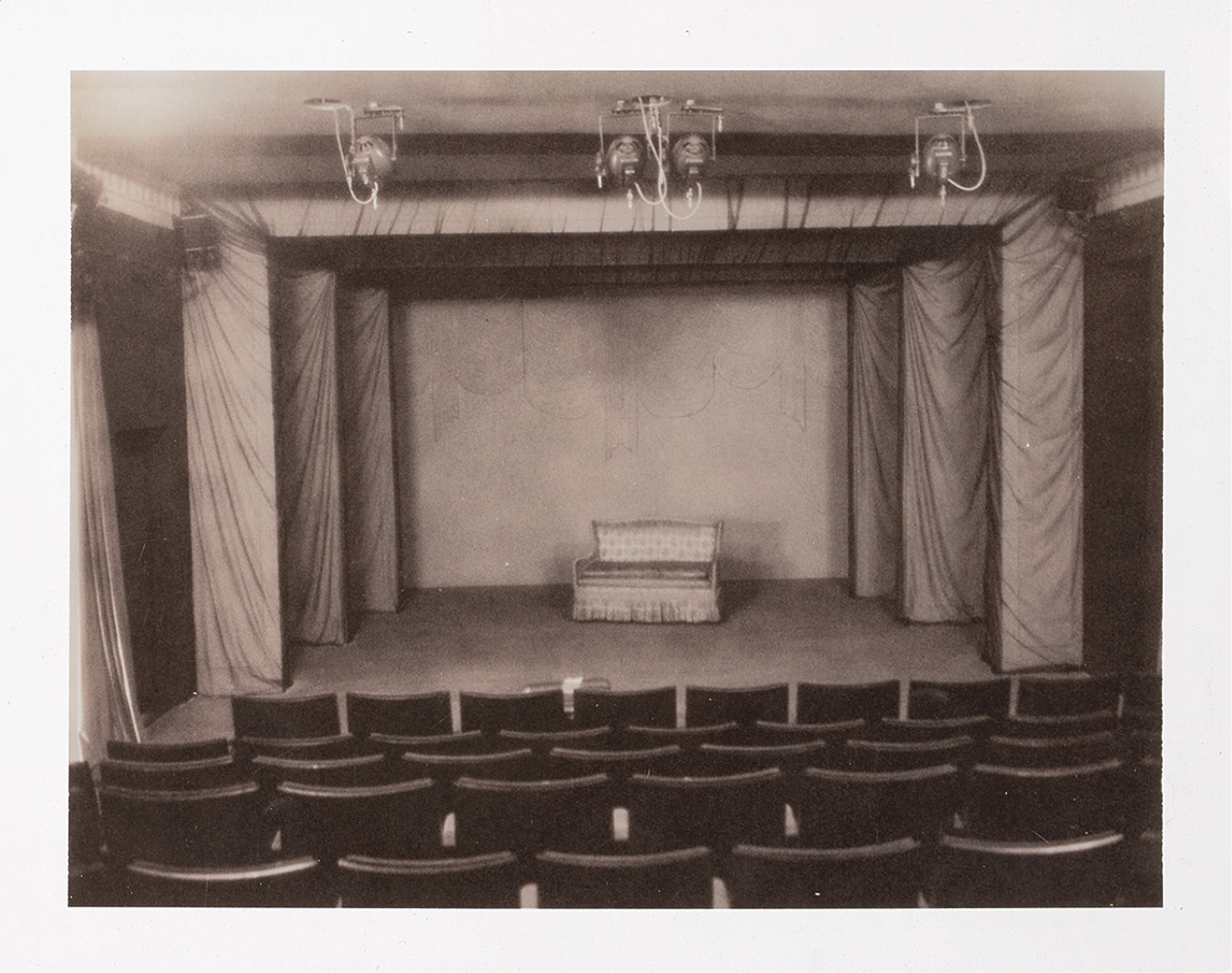

first row

Local Theater, 1975

It's an entire philosophy and there is no middle ground. You want the film to fill your entire field of vision. For me, the first row is where you can stretch your legs, but you’re so close to the screen that you have to sink down, really almost lie down. The only good alternative is the second row. You can put your knees against the seat in front of you. That’s a great fetal position for watching movies. At the Cinémathèque française, where I watched a thousand films in the course of one year, I got used to the second row because when Henri Langlois was giving his little introductions, he was walking up and down in front of the first row, so you couldn't stretch your legs. That fetal position of the second row is almost like the John Lennon photo by Annie Leibovitz on that famous cover of Rolling Stone.

Do you like to sit dead center or keystone?

Center. Center, second row is the ideal spot.

You like the image to be fully immersive.

Yup. With CinemaScope, you even have to turn your head left or right to take it all in. Anthony Mann’s Western Man of the West [1958] was the first film where I really noticed the physical effort to watch ’Scope when sitting in the second row, and I liked it.

The Swiss author Robert Walser wrote in 1909 about attending a production of his favorite play, Friedrich Schiller’s The Robbers, and apparently in fin de siècle European theater, the front row was designated only for the critics.

The cheap seats. [Laughs] I do not like those at all in the theater. I think you are just embarrassingly close to the actors. You get their spit on you and you see them work so hard.

Dance as well. You can’t appreciate dance, you can’t take in the entire mise-en-scène, in the front row.

Especially as you’re often sitting so low there. Pina Bausch for instance. In the front row, you’re on the floor level, and that’s not good. When we shot Pina [2011] in 3D, the camera was always at the eye level of the dancers. In traditional movies, it’s a different thing. A lot of films are shot a little bit from below. The low angle in movies makes it even bigger as an experience. It’s the adoration perspective.

There was one amazing exception to all this in my moviegoing life. My favorite theater in Munich during my student days had a nice, wide space behind the last row, where you could walk back and forth and lean on a half wall. This is where the smokers stood. I was still smoking heavily, and I liked the perspective of watching a movie as a walker.

Would you actually walk, or would you lean on the balustrade?

Both. Yeah, I would lean on the balustrade, take a few steps, walk to the other side, watch for a while, light another cigarette. If I could design a theater, I would design that walking section, even if smoking isn’t an option any more. Just seeing the whole audience in front of you and seeing the film at the same time is the funniest feeling, like being an impresario or the theater manager. You’re not part of the audience, you’re strangely in control. Ah, I somehow loved it. To be able to smoke, walk and watch a movie! You could even take notes without bothering anybody! I had that experience only once, in that little theater in Schwabing.

What about sleeping in theaters?

It’s one of the best things.

Right? Some of the best sleeps I’ve ever had in my life were in cinemas.

I only sleep in movies I like. I’ve never been able to sleep for a moment in anything that I didn’t like.

Because you’re agitated? Why?

You don’t feel safe. With a bad movie, you’re a little bit on the edge, you can never close your eyes. But with a good movie, you’re safe and protected like a baby and you can let yourself drop into it and then fall asleep and wake up realizing, “Well, next time I see this movie, hopefully I see that part I missed.” Funnily enough, this was especially true with The Big Sleep [1946]. I’ve seen it 10 times. I still think there are scenes I’ve never seen.

Well, it’s a pretty confusing film to begin with—all that wonderfully convoluted Raymond Chandler plotting.

Yeah, it is. But it’s also the quality of the dialogue. It’s so soothing. It’s easy to sleep in movies with lots of dialogue.

You’re being lulled. By human—

Language, especially that sort of dialogue. That classic fast-talking Hollywood tradition is beautiful.

Is it more in your own language or in other languages?

It works in any language, I guess. Actually, it’s even more sleep-inducing to see a movie in another language. To see a movie by Ozu, with people speaking in Japanese, I mean, after 10 minutes I have a hard time not sleeping. I feel so safe, nothing can go wrong.

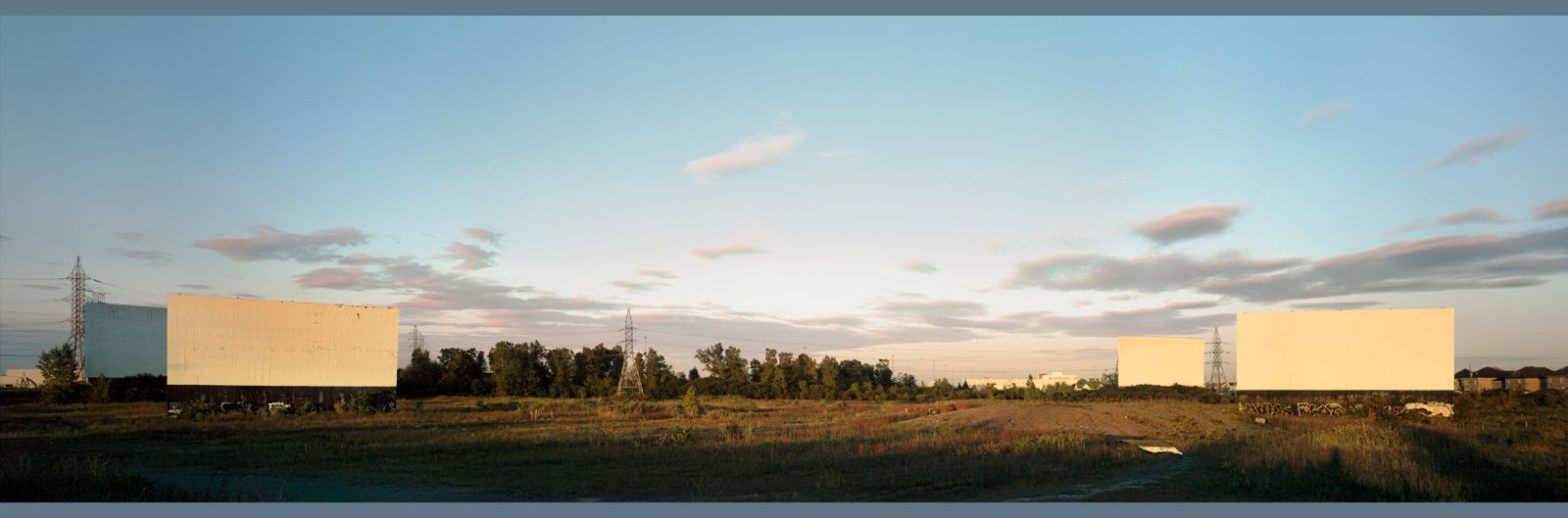

Four Drive-in Screens, Montréal, Canada, 2013

“I only sleep in movies I like. I’ve never been able to sleep for a moment in anything that I didn’t like.”

Were you taken to films as a child by your family?

No, I wasn’t allowed to. I became a projectionist at the age of five. We lived in my grandfather’s pharmacy. The rest of the house on top was gone because of the war, but the pharmacy was intact, and in the basement was a lot of stuff. One night my father said, “Oh, wait, I just remembered something.” And he disappeared into the basement and came back half an hour later with an old wooden box. Inside was a 9.5mm projector, which is a format from—

Pathé-Baby.

Yeah. And it had a hand crank, and he put in the plug and the lamp still worked. It had survived the war. Inside a drawer were a dozen little reels, each a minute long. Scenes from slapstick films and some early animation. Some Buster Keaton, Mack Sennett, silent Laurel and Hardy. No Chaplin, though. I don’t know why he was missing. One of the short animation films was an early German comic strip with two characters, and I’ve never been able to find those in any archive. I liked them a lot.

My father showed me how to thread the projector, and he put a white linen over the door. I was in awe because I’d never seen moving images before. I wasn’t in school yet, and this was my very first impression. I got very good at threading the film and discovered you can also go backward and stop and go fast-forward. I became the projectionist of all my friends’ birthday parties. This was a big attraction because none of us had television, so most of us had never seen a movie. It was endless laughter and pleasure. Maybe my later addiction to cinema started with being a projectionist and loving it.

And it sounds like your dad had used it as well when he was a kid.

Yes, and it somehow survived the war.

Did you and your dad also make home movies?

Oh, yes. My father bought an 8mm camera, a Leicina. He filmed all the vacations, and every now and then he handed the camera over to me. And a few years later, the model improved to Super 8. I made little films with my Catholic Boy Scout group, where I was the leader. They were 10 and I was 15, 16. My brother became an actor in front of my camera, and I made him do things. Drive-bys on his new bike. “No, do it again. A little bit farther from me.” I liked being behind the camera. I also did fancy panning shots with my parents at the beach.

Were those the ones you used in Until the End of the World [1991]?

Yeah. That was some of the footage. That was really my first filming experience, shooting 8mm. I biked to France when I was 16 with friends for four weeks and documented the whole thing on Super 8. My first visit to Paris as well became a 20-minute documentary. I also had my own darkroom when I was 16. My father was an avid still photographer during the war, which he spent as a German army surgeon in the south of France. He was very lucky he wasn’t sent to Russia.

And he taught you how to print photographs?

No, I learned from a friend and from books. My father had strictly taken pictures of people. I took to industrial landscapes. Because there were no people in my photos, he wondered why I would even care, was even a little irritated that I shot out the window just because I liked the sunset. The Ruhr district [in western Germany] was extremely polluted at the time, so there were the most amazing yellow and red skies. We were really close by—you could see the chimneys just a hundred yards away. It was very dirty, and I thought it was extremely beautiful. I also painted a lot of that in watercolor.

From left: In Coober Pedy, Australia, c. 2007; Open Air Screen, Palermo, 2007

Sounds a lot like Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert [1964], the exquisitely beautiful pollution. Was your fascination with form and structure? Or with color?

Form and structure at that time. I made a long trip walking the entire coast of Brittany, from Saint-Malo all the way around, for four weeks. I did a lot of drawings of rocks. That was my first journey all on my own. I was 18. I only took a handful of photos, one reel of film.

It is interesting how many Germans go on these wanderlusts. The animation filmmaker Oskar Fischinger made a stop-motion film in 1927 of his walk from Munich to Berlin.

My longest solitary walk was across the Alps to Venice. I’d done a play in Salzburg, Across the Villages, by Peter Handke, my only theater experience as a director. It was so beautiful that I didn’t want to touch theater again. I thought it was never going to be that good again. The theater had a huge CinemaScope stage and a roof that you could open, so you would have sun come in, and we only played it four times. Anyway, from Salzburg I walked to Venice, to the film festival where in 1982 The State of Things was in competition. I had one slim book of poetry with me and crossed the Alps to Italy, actually via Slovenia. It took three weeks because you had to do a lot of zigzagging across the mountains. Anyway, I got to my hotel in Venice, the Hotel Des Bains, and the big imposing watchman didn’t want to let me enter, a guy in short pants and big shoes and a backpack. Ten days later I checked out and pulled the Golden Lion from the backpack, and I showed it to him and we had a laugh.