Wimself Pt. II

By Josh Siegel

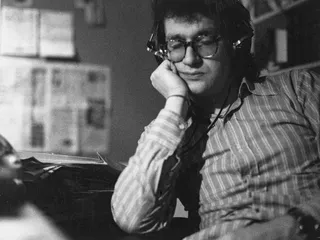

Wim Wenders in the 1970s

WIMSELF PT. II

By Josh Siegel

Photography by Wim Wenders

A candid and freewheeling conversation in four parts with Wim Wenders, the poet laureate of New German Cinema

December 9, 2024

Immobile Home, Texas, 1986; Subterranean Homesick Blues, Germany, 2011

HOME

Wim Wenders: The conception of home changed for me over the course of my life. For the longest time, home was strictly the German language and nothing else. It was not a place, it was not my parents, it was not a partner I lived with. It was definitely not Germany, because I only wanted to leave it behind. But it was the German language, and inside even the smallest suitcase I would always have one book. There’s a beautiful tiny edition of the complete [Rainer Maria] Rilke, and it’s ideal to travel with. I always had a book in my own language with me no matter where I went. When I crossed the Australian desert, too. There I found only German names. All those mountain ranges, lakes and rock formations were “discovered” by some bloody German. Like in South America, where you find the most amazing places with German names, baptized by Alexander von Humboldt. So, yes, there’s a long tradition of the solitary German wanderer and his wanderlust. After living for the first time in America, from ’78 to ’84, I had to go back to Germany because I realized I was dreaming in English, and that really worried me.

Josh Siegel: Why did it worry you?

It worried me when I realized I threw in English expressions in conversations. I always hated that. I didn’t want German to become my second language. In the end I also came to terms with being a hopeless German romantic who could never, ever become an American. It had taken the whole long American detour to accept that Germany was my home country. It wasn’t even Germany as such—it was the city of Berlin. And the German language.

You’re reminding me of what Bruno Winter [Rüdiger Vogler] says in Kings of the Road [1976]: “The Yanks have colonized our subconscious.” Well, I imagine that Rilke was an important inspiration for Wings of Desire [1987].

Yeah. He was essential to my quest for finding characters with whom I could narrate the city of Berlin. I finally ended up with angels. They were my only option to go back in history and really cross the city sort of vertically and horizontally. I had no choice. And they were originally suggested by Rilke, you’re right. His angel poems are really among my favorites. Almost against my better judgment I chose guardian angels as my main characters. I doubted that choice for the longest time. What finally convinced me that I had done the right thing was finding the point of view for the angels. That changed my way of thinking.

In what way?

If the angels would see the same way that we see, or that the cameras sees, it would betray the whole idea of the film. I wanted to take these angels seriously, so I had to take their look at us seriously. They had to look at us more lovingly than cameras normally capture a point of view. Even [cinematographer] Henri Alekan was very confused. “How should I make my camera see more lovingly?” he asked exasperatedly.

You do it with light, I suppose?

Yes, but that’s only part of it. Henri was doing a fabulous job with the light anyway. But I told Agnès Godard, Henri’s camera operator: “You must somehow express in your camerawork, in the way you see through the lens and pan and move the camera, that it shows the look of the angels. We must feel a difference! And I have only one clue: You have to invest more of your own love and affection into the shots that are clearly from the point of view of the angels. If you invest it, it will show.” Agnès really took it seriously. And so did our dollyman, who was a genius in moving the camera anyway. He did each and every crane or dolly move of the film all on his own, without help. After a while Agnès said: “Wim, I’m slowly getting what you mean. I do see a difference. But as you said, you have to pour your own love into those shots and into what you see. Otherwise it doesn’t work.” I said: “Exactly. We all have to invest more. Otherwise our angel characters are strictly make-believe.”

The Elbe River, Germany, 2014

Like a caress. When you said it changed your way of filmmaking, I can’t help but think of Perfect Days [2023]. There are shots in that film that are invested with such beauty and love.

When you invent a character like Hirayama, such a benevolent person, somebody who chooses a different life, a life of service, you have to do the same work. You have to be able to translate the kindness of his gaze. The actor [who played Hirayama], Kōji Yakusho, has the kindest pair of eyes I’ve ever seen.

It’s patient observation, the fact that he takes such pride and care in his work. We were talking about addictions, and this is a good example of how addictions can be a meaningful, life-sustaining, nurturing thing.

But maybe there’s another word for that than addiction. We talked a lot, Kōji and I, about how he perceived his job like a Japanese craftsman who also repeats the same thing every day. People do something in wood, clay, bamboo, whatever craft it is, but each piece has to be perfect, even if they all look the same. By then Kōji had already taken his crash course in toilet-cleaning with the real guys who do it, and he said they weren’t all that different from craftspeople. It’s also a love of structure, a structured life. The absence of structure is something that most people really cannot deal with.

Or a love of ritual, of materials and handiwork, and of repetition. If there’s anything to be learned from [Yasujirō] Ozu, the idea of repetition is essential to any kind of meaningful life.

Here’s a man who knew how to invest love and care into every shot. An outpouring of love for his actors and his characters—even the “villains,” the family pain in the ass. His cameraman Yūharu Atsuta told me sometimes they couldn’t shoot, because Ozu would move a sake bottle a little bit here, a little bit there, and he would look through the viewfinder and just shake his head. He spent endless time just arranging.

That’s a beautiful approach to making art. Like ikebana, the Japanese tradition of flower-arranging. It’s even a way to live well: In the end, all you’re left with are the little things, arranged and observed with a loving gaze.

And everything has to be perfect. So, yeah, the sheer gift of his movies is that they are made in a world where little things matter just as much world history. Little things rub off!

LANGUAGE

.jpg)

Used Book Store, Butte, 2000

It’s a virus, according to Laurie Anderson. Language is addictive.

In what way?

If you really like language, when you have it in your bones, in your brain structure, then as soon as you write something down it really gets obsessive. For example, now I can only write on a computer. Seeing and writing and thinking have become for me one single process. Typing it means seeing it, means improving on the idea and thinking clearer at the same time. I don’t think very well when I write by hand. A handwritten script is completely impossible to conceive of for me. My friend Peter Handke does everything in handwriting, very small.

Like Robert Walser’s microscript. Some authors need to be able to write in longhand.

I’m the very opposite. My brain works in a much more organized, clean and authoritative way. I’m always a bit appalled if I look at my handwritten notes, because they reveal muddy thinking. Then I type it up and realize, “Wow, now we’re talking.”

Paris, Texas [1984] was written in English together with Sam Shepard. Do you usually write your scripts in German? What about Perfect Days, which ends up spoken in Japanese?

I love writing in English. I like writing in German, too, but if it’s something that will end up in English, I’d rather write it in English than have to translate it. The script for Perfect Days had to be translated into Japanese, but it was written in English.

The Japanese have a strange thing with language. You realize in Tokyo how many things are written in nonsensical English. It’s often unbelievable, often downright funny, completely invented English. They massacre the French language even worse. The lyrics of the Japanese song in the film, for instance: I wanted to find out what she’s really singing; I got one translation and then looked it up somewhere else and found something entirely different. Language for them is not as definite as English or German is for us. It depends a lot on what is spoken.

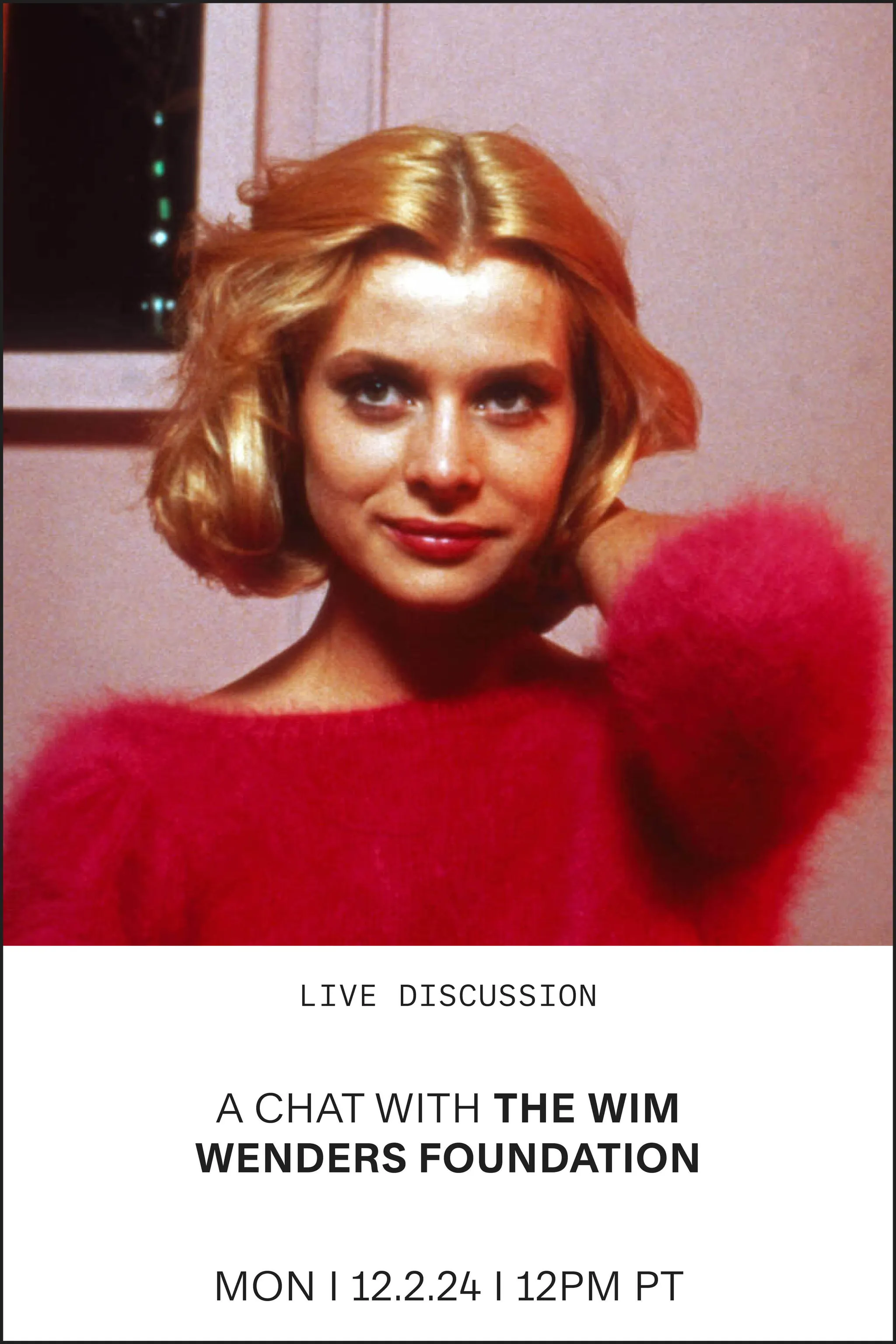

BEING WITH CHILDREN

Alice in Instant Wonderland, New York, 1973

Being with children is a different way of being; shooting with them needs a different attitude. Alice [from Alice in the Cities, 1974] was the real prototype for that. In films, I feel, the way children see the world and understand what’s happening is such a healthy antidote to my own or other grown-ups’ visions of stories or priorities. A child just makes all of that irrelevant. Having a child in a film can for me be almost necessary in order to correct the approach of the film. In Kings of the Road, for instance, the two protagonists are mostly silent, but eventually they have an outburst, a real fight, and tell each other things. You find out that one of them, Kamikaze, is a child psychologist. Later, he has this most interesting encounter with a boy he meets in a train station. He wants to swap his suitcase for the boy’s notebook. They get into a funny conversation about naming things they see around them. After the two men constantly insult and correct each other, meeting this child is for Hanns Zischler’s character a way to get back to life and be himself again.

Do you like working with children? When you worked with the actress [Yella Rottländer] who played Alice, she improvised, if I recall, no?

She made it very clear from the beginning: “We can do this two ways. If you insist that I say what you’ve written, you should know that I will be bad. If you just explain to me what you want me to say and then I can put it into my words, then I’ll be good.”

That’s pretty astute.

Rüdiger [who plays Philip Winter in Alice in the Cities] found a nice way to deal with her improvising—it became quite loose. Eventually we went one step further. Alice said to me, “Sometimes I feel you say ‘Cut’ too early. Would you let me say ‘Cut’ in my scenes?” That turned out quite beautiful because she always waited a bit longer, to see if something else would happen. And if she liked what happened, it would go on, and if she didn’t like what happened, she said, “Oh, no, cut. I should have said ‘Cut’ earlier.”

That’s beautiful. Whatever became of her?

She made one more movie, a television movie. I met her the next year and she said: “Wim, I’ve given up acting. It was not like it was with us. I had to learn all my lines.” She became a costume designer for movies. Ten years later, as a mother of two and almost a generation removed from all other students, she took her medical exams and became a doctor. She appears one more time, as Vogler’s angel in Far Away, So Close! [1993].

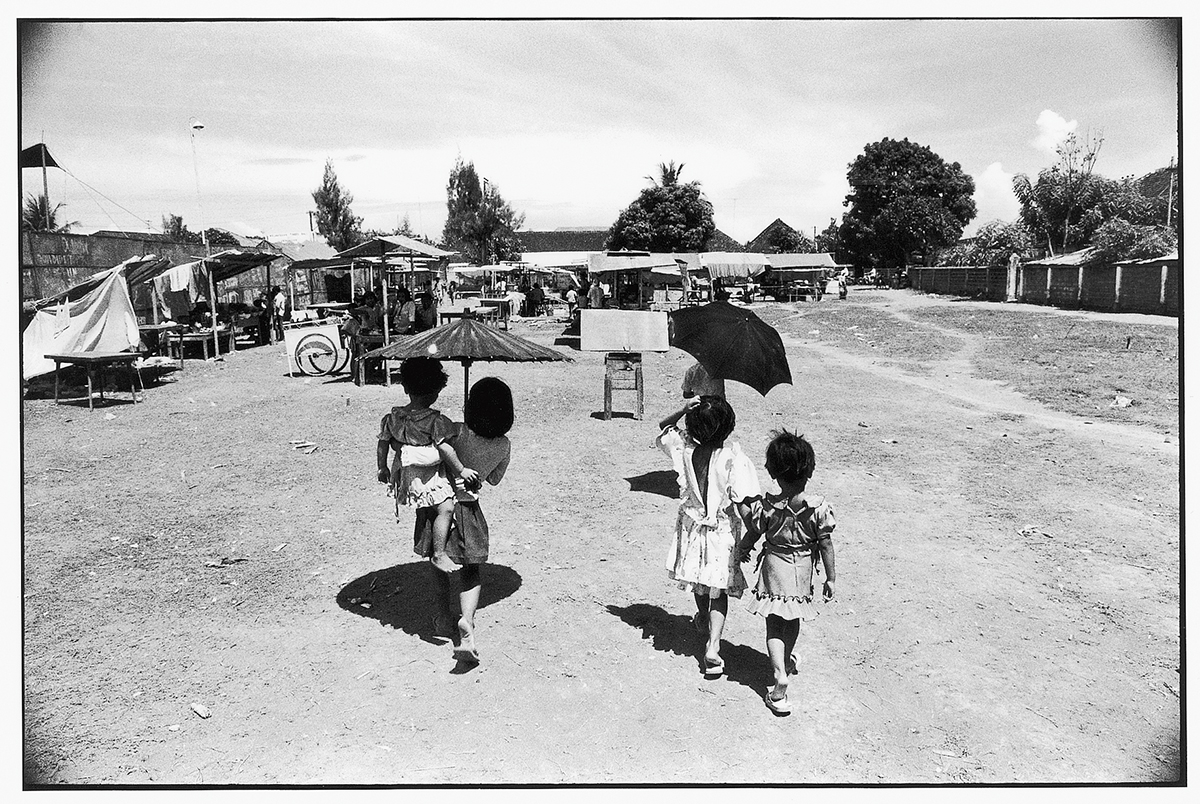

On the way to the circus, Denpasar, 1977

DIARIES

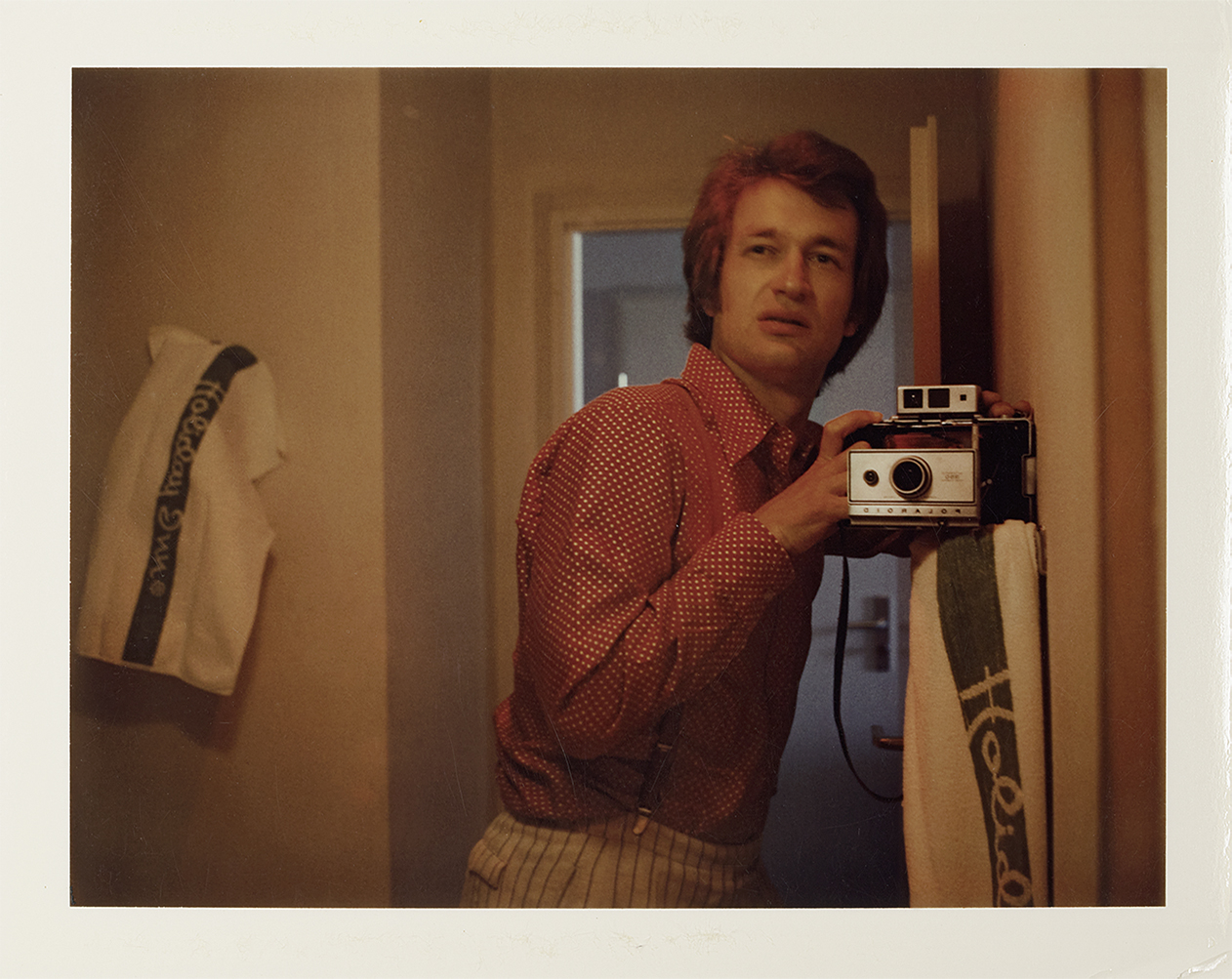

Self-portrait, 1975

I still keep diaries.

You’ve been doing it since you were a teenager?

Yes. I have shelves of notebooks. I’m also a compulsive buyer of notebooks. For a while I used these beautiful...they were virgin books, just empty pages, but this one had a real hardcover in blue felt. That was the ultimate! I bought all I could get and used them for years. But my problem is that I never finish them. I always write a few pages and then start another book. So that shelf is full of half-written—

Why do you think that is? Tabula rasa—you need to start fresh?

I guess so. A new idea needs a new book. Anyway, I have a huge number of diaries in my own handwriting, so it’s very hard for anybody afterward to make sense of them.

Do you want the Wim Wenders Foundation to eventually make the diaries available, or are they private?

It’s a good question. They could only be made available if I help to decipher them. They’re a strange mixture of movie ideas; notes on places, on pieces of music; impressions, worries, plans, scenes that I saw or heard and wrote down. Some of it is private stuff about how I felt. I’m not sure I want people to read that. But I just keep doing it. Now I’ve found a form that forces me to be more disciplined. It’s a five-year diary. Every page [records] the same day over five years. I cannot possibly lose it, so I pay attention. Actually, I do it now every evening, and I only have the limited space of five lines to work within.

But you also refer back to what you did a year ago, which can spark different thoughts.

Yeah, it’s interesting. Today was the 738th day of the war in Ukraine. I know because I’ve numbered the days ever since the beginning, so I now know we’ve entered the third year. It gives a strange sense of historical continuity, but it helps me to structure my otherwise unstructured diary urge.

Do you have a favorite pen?

I always use the hotel pen.

So you don’t fetishize fountain pens?

Those? Oh, of course I fetishize my fountain pens. I have much better handwriting with a fountain pen. My favorite is in Berlin, but I don’t travel with it because I lose pens too often. Right now I have three hotel pens on me. My favorite fountain pen is a handmade pen by a friend of mine. I keep it on my desk at home. Donata [Wenders’s wife, a photographer, filmmaker and writer] made a little film on him, and I did second camera because I like the man’s work so much. We spent a week with him on one pen, from beginning to end. He’s studied some of the crafts in Japan, and now he’s big in Japan, like a star. They travel to Hamburg to buy one pen from him.

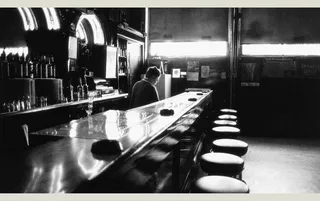

loneliness

Bar in Butte, Montana, 1978; Wim Wenders in the 1970s

“I like the loneliness you sometimes have to fight for.”

I like the loneliness you sometimes have to fight for. One of the things about photography is it’s something I can only do when I’m alone. My photographs need me to be in conversation with a place. Trying to find its story by looking and listening—they demand an involvement that you can never have if somebody’s next to you, even an assistant. I’ve always schlepped my cameras. Even in Australia I schlepped all my heavy-duty panoramic equipment and tripods. And my Aboriginal guide called me fotojarra, which meant “the idiot with a camera,” because I wouldn’t let him walk up the hill with me. I said, “No, you stay here by the car and I walk up there.” I just need to be alone.

Just for clarification, we differentiate in English between loneliness and solitude. The first has a more pejorative connotation.

I’m not afraid of either. I have a theory that only people who know how to be alone also know how to be with others. Thinkers and writers who are often alone, either they end up unable to be in society and their thinking gets pretty obsolete, or they’re very good in society and they’re very open and curious. When I realize that somebody who is a good thinker is also a social idiot, I start doubting their thinking.

So being alone is not only being by yourself on top of a hill in Australia; it can mean being alone in a crowd. I think some of the greatest pleasures in life are spent in a city alone, being a flaneur.

Totally. Here, too, the movie theater is the best place.

Jean-Claude Carrière told me that he learned something important from Jacques Tati about writing scripts, that Tati first came up with plots, characters and dialogue simply by sitting in a café, watching the world go by.

It’s indeed a great pleasure. I had a remarkable experience with Tati because I loved his films very, very dearly. It was here in New York in the ’80s, at the Paris Theater. They played Traffic [1971]. It was a Sunday matinee screening, and I was sitting in my second row. Behind me were maybe 10, 15 empty rows and then, like, a hundred people sitting far behind me. As always when Tati appears, I laughed. The room was dead silent. “Who is this idiot in the second row?” Anyway, there’s no reaction behind me, almost hostility. So I realized, Wait a minute, I can do something here. I began to exaggerate my laughter. By the end of the film, the entire theater was shaking with laughter all the time. I had them. I made it infectious.

the digital temptation

.jpg)

Portrait, Texas, 1983

As I’m prone to addiction, an iPhone is a very dangerous instrument to me.

In what way?

I spend too much time on it. Take too many pictures that are not photographs, write too much stuff and look up too many things, get too many messages, don’t see enough.

There was a beautiful study done in New York with two groups of people. At the end of the day, the people who were given a map of New York wrote 20 pages full of details, remembering everything. The people with the phone navigation did not remember much. And that is exactly my experience.

Well, the greatest city in the world to get lost in is Venice, and the good news is that GPS can’t keep up with Venice. GPS is defeated by it—the city is too labyrinthine. So you can’t help but get lost.

Yes, sometimes I force myself back to maps because I love maps. I’m addicted to maps, like too many other things. Now you don’t get them anymore, but gas stations, for me, were places to gas up and buy maps, especially in the American West. I came back with my car full of maps. I loved staring at maps in motels in the West, reading the names of places, mountains or rivers and deciding where to turn to the next day just based on names.

This brings us back to the idea of loneliness. Social media, the illusion of an immediate connection to friends through texting, these are meant to be an antidote to loneliness, but of course they only deepen our sad sense of estrangement.

Yup. All of that is part of the digital temptation. We mismanage our lives since we have smartphones, so sometimes I force myself not to rely on them. Taking pictures with my analog cameras is related to body language, to my arm and hand. You could never “listen to a place” and take its picture with a phone!

You’ve never been tempted to make a film with an iPhone like Steven Soderbergh or Sean Baker?

Well, I was one of the first to do it. We did it already with the first iPhones. I made films with my students. The rule was only iPhones, and I made one of myself. There are a handful of shots in Perfect Days that I did myself.

With an iPhone.

Yeah, you don’t see the difference. Well, you do see it, if you know. Even if it’s in 4K and looks pretty good, it’s totally limited in color correction. We took pains to shoot most of Perfect Days with old Canon lenses. We shot with a high-tech digital Sony camera but used Japanese lenses from the ’50s.

Amazing. The kind that Ozu would have used?

Possibly. We found software for my iPhone to get closer to that look, like in the car when Franz Lustig [the DP on Perfect Days] is shooting Hirayama. There wasn’t much room in the car, so I did a lot of second unit on my iPhone for the POVs, looking through the windshield. So, to be fair, it can be a useful instrument.

The digital temptation is a paradox because you’ve always been on the cutting edge of digital technologies. Until the End of the World [1991] featured the very first dream sequences produced in high-definition digital video. And if I’m not mistaken, right around the time you shot the film—a film that imagines a not-too-distant future of video phones, GPS, search engines, memory sticks, even Zoom—the World Wide Web made its debut.

Those dream sequences were the first digitally generated images ever to find their way into a movie. We worked in an editing suite run by NHK in Tokyo, equipped by Sony with prototypes of editing machines to transfer film to digital high-def. They weren’t even selling them yet. And yes, Until the End of the World ends with a Zoom call! But even that movie shows the digital temptation. Even when it didn’t yet exist, when digital technology was just being imagined, what happens to Solveig Dommartin’s and William Hurt’s characters is a “digital virus.” Those little handheld monitors that offer them open access to their dreams turn out to be completely addictive devices for them.