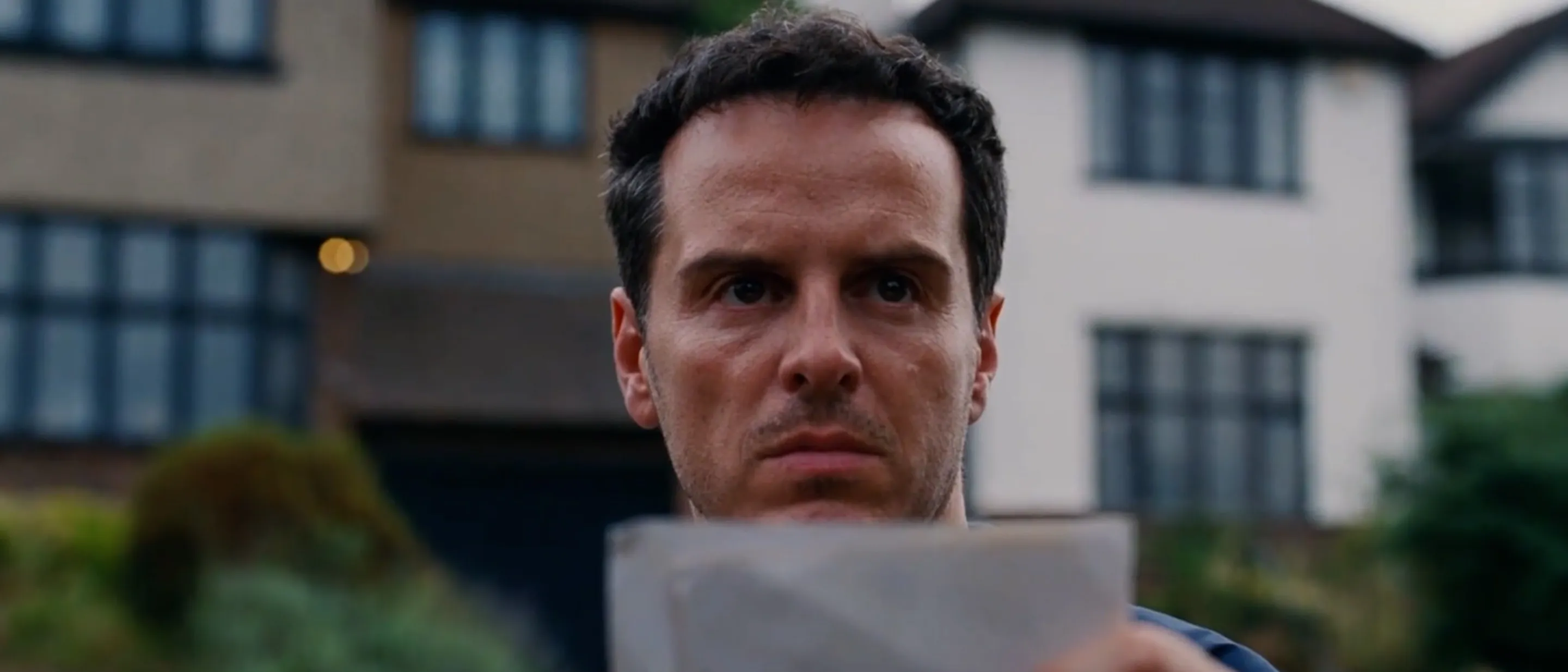

Andrew Haigh

“Cinema is not here to make you feel safe,” says Andrew Haigh—a credo embodied in his own filmmaking as well as his curation for Galerie. Building on his early career as an assistant editor for Ridley Scott, the British-born Haigh has created an award-winning body of work, including the groundbreaking queer romance Weekend (2011), the tender marital saga 45 Years (2015) and the metaphysical grief drama All of Us Strangers (2023). For his personal cinematic reference points, Haigh cites classics by Billy Wilder, Agnès Varda and Ingmar Bergman alongside art-house horror, gritty social realism and global stories of connection and longing. What makes film remarkable, observes Haigh, is its capacity to expand consciousness. “You come out of the cinema and you feel like you’ve had a dream for two hours, and that lingers and it builds and it resonates,” he says. “That’s a really powerful thing.”

A PERSONAL MESSAGE

my FILM LIST

Click each title to discover our curator’s notes and where to watch

This a bold and stunning piece of work, in both story and style. You can tell in every frame of the movie that Welles wanted to surprise. This noir-melodrama is a technical tour de force, operatic but down in the dirt, surrounded by so much moral filth that you feel like you need a shower after you’ve seen it. Of course the studio tried to fuck with the film. They were scared of invention. Terrified of the dark center in all of us. But I’m very glad that filmmakers like Welles, in the context of American cinema, kept trying to push.

{{ All Items }}“Nobody’s perfect” is the last line of the film, but this movie is as close to perfection as possible. I watched it when I was 11 years old and then watched it about once a week for about three years afterward. I know every scene, almost every line, and it still makes me laugh. It works so beautifully as a mainstream comedy but is surprisingly subversive at the same time. You almost want Jack Lemmon’s Jerry to end up with Osgood Fielding III. It may not be a queer film, but it certainly spoke to my young queer self.

{{ All Items }}I was working as an usher at a cinema in the mid-1990s. They screened an old 35mm print of L’Avventura, not with subtitles but with an earphone commentary with someone explaining the dialogue. I was on duty at the back of the cinema and didn’t have the earphones, so I couldn’t understand any of the dialogue. It didn’t matter. The film left me stunned. Everything was expressed through those crystalline images. The theme emerged through the position of the camera, the blocking of characters in space. I left the cinema wanting to make films, and I often return to Antonioni for inspiration. The wind blowing in the trees as Adam sees his father for the first time in All of Us Strangers is definitely inspired by the wind billowing through the trees in Blow-Up.

{{ All Items }}I watched this film in the lead-up to making Weekend, and both were shot in Nottingham. In my movie Glen wears a T-shirt with the name of this film emblazoned on it. I came late to the British New Wave, but this is a pure classic of the genre. Albert Finney oozes charisma from every pore, and while he isn’t always particularly likable, you can’t keep your eyes off of him. I always think there is something queer about this film, if queerness is about not letting conventional thought destroy your life. Don’t let the bastards grind you down. I’d also recommend The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner with the legendary Tom Courtenay. It makes for the perfect double bill.

{{ All Items }}I love this film. It’s a mainstream Cold War thriller with a sharp and twisted art-house heart, perhaps the first of the American New Wave films. Beautifully shot with stunning deep-focus imagery, it constantly surprises. Angela Lansbury is a revelation and makes me think a lot about the power of taking an actor who is perceived in a certain way and then shifting that perception, not wholly but enough to throw the audience off-balance. Throwing the audience off-balance is an essential thing to do. Cinema is not here to make you feel safe.

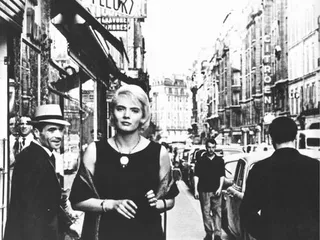

{{ All Items }}Over 90 minutes, in what feels almost like real time, we watch a woman come to terms with what her life has meant. It is not easy to make a philosophical story feel as light as air, but Cléo from 5 to 7 somehow manages it. Whether Cléo is choosing fur hats and looking at her reflection in the mirror or talking to a soldier as they wander around the park, we feel the big questions of life are bubbling beneath the surface. Agnès Varda is a master at teasing out the profound. I watched this over and over again when I was thinking of making Weekend.

{{ All Items }}This a harsh and thrilling movie, experimental for Hollywood at the time. Boorman seems underrated as a director in a way I’ve never quite understood. He brought an uncompromising European sensibility to his American films, and they are all the better for it. This is a disorienting, nonlinear piece of work, brilliantly shot and edited. There is a scene when Lee Marvin walks down a long corridor and we hear the click and the clack of his footsteps as we intercut with the past. A woman gets dressed and goes about her day as Marvin follows her. But the footsteps keep going from another moment in time, building an exquisite tension that you know is about to explode. And explode it does, with the kicking down of a door and gunshots into a bed. It’s just a brilliant moment.

{{ All Items }}I was working in Prague as an assistant editor on the movie Shanghai Knights. During the day I was syncing dailies of Jackie Chan and Owen Wilson, and at night I was watching the caseload of Bergman DVDs I’d brought with me. Bergman clearly influences many filmmakers, and I’m no exception. Like a great painter, his close-ups reveal the deepest of emotions lurking beneath the hint of a smile. Cries and Whispers is my favorite of his films, an existential howl of a movie. The red dissolve that seems to emanate from Liv Ullmann before it overwhelms the screen is one of the greatest uses of color in cinema. She stares directly into our souls, begging for our help. We are complicit in her pain but can do nothing to help her. It’s pure devastation.

{{ All Items }}I could put a few of Roeg’s films on the list, but this is the most important to me. Watching it is like falling into a dream. The tone is masterfully controlled yet elusive and strange. Nothing is what it seems. Is it a horror film or a love story? Is it a study of grief? It is all of these and so much more. It exists within the cracks of genre and is all the more effective for keeping the audience off-balance. I’m very aware that the sex scene has inspired every sex scene I’ve ever done. It is tender and emotional, but most importantly it is integral to the story. Again comes the color red. The emotional power of red.

{{ All Items }}Cinema is about feeling. How does a film make you feel when you watch it? And sometimes, just sometimes, a film can become part of your life, your history, your understanding of the world. Watership Down, which I saw when I was about eight years old, was that for me. It is a film meant for kids, a story of a group of rabbits fighting for their lives as they try to find a new home. I hear so many British people of a certain age talk about this film, about how it fucked them up. I would say that it didn’t fuck me up, but it did give me insight into the terrifying existential struggle that is our lives. It is Cries and Whispers for kids, and all kids should see it. Plus, it has a funny seagull in it.

{{ All Items }}This was my first Kubrick film, and while it is not necessarily his best, it is the one that found its way into my dreams and scared the shit out of me. Still now if it comes on the TV, I’ll watch it to the end. The way the dread slowly builds to a breaking point is masterfully achieved. And there is the color red again. I was a big teenage fan of the book, too, and watching the film helped me understand a little more about adaptation, how the essence can change, and how a screenwriter and director can make it their own. You can love the book and love the film, but it doesn’t have to be for the same reason.

{{ All Items }}I can still feel this film. Every time I watch it, I feel like I did as a kid. The fact that I was around the same age as Elliott when I first saw it and my parents had just gotten divorced makes this film an obvious fit for me, but it is more than that. This film harnesses magic. I don’t know if it is the purity of the performances, the soar of the score or the sincerity of the emotion, but it all comes together so beautifully. I’m not convinced I could be friends with anyone who doesn’t like this film or doesn’t cry when E.T. leaves at the end. Sometimes cinema can, and should be, pure heartfelt emotion.

{{ All Items }}Lynne Ramsay’s first two features (this and Morvern Callar) are always going to be on lists like this because they are such bold, beautiful works. The films are remarkably and thrillingly individual, as if Ramsay had found something new down the back of the sofa of British Social Realism and made it her own. Ramsay instinctively understands you can get closer to true feeling, and hence the truth of a person, when you combine the reality with the fantasy. She knows where to find the magic. Who would have thought that in the middle of this film we’d see a mouse travel to the moon? It’s pure transcendence.

{{ All Items }}I love many of Michael Mann’s films, but this is my favorite. Again, like with The Manchurian Candidate, I’m so impressed when a mainstream movie takes on the best of art house. This works beautifully as a thriller or a film about journalism, but it is the pure craft of filmmaking that takes your breath away. The camera is in complete control. There is a scene where Wigand, played by a never-better Russell Crowe, sits in a hotel room contemplating the weight of his actions as a mural behind him comes alive. As the camera twists, we are brought ever deeper into the man’s psyche while the film is torn from its moorings. The effect is thrilling. I need to watch the film again.

{{ All Items }}I wish I could have made this film. It speaks so acutely to loneliness and the nature of melancholy. How we let it overwhelm us, find comfort almost within it. Over the years I have taken a lot of inspiration from this film, with its careful pacing, the masterful blocking of characters in relationship to the camera, the expressive sound design and the minimal but razor-sharp editing. It is a profoundly serious film yet has a lightness, a humor always rooted in the contractionary nature of the character. And no one shoots snow like Nuri Bilge Ceylan.

This was the first of Martel’s films I saw, so it holds a special place for me. Martel, like many on this list, is a master of tone. In every composition and with every choice of sound, the director wants us to be curious, ask questions and look deeper. She makes us aware that what is outside of the frame is as important as what is inside. In doing so, the film opens up inside our own heads. It feels like you and the filmmaker are dreaming together. I can’t remember much of the plot, but I can remember the power of the film.

{{ All Items }}

MY CREATIVE PROCESS

Exploring craft and influence

Galerie Originals

Andrew Haigh The Scene: All of Us Strangers (2023) WATCH