Mike Mills

Equally informed by a childhood spent skateboarding and playing in punk bands in coastal California and the downtown scene of pre-millenium New York City, where he studied conceptual art at the Cooper Union and launched a career as a graphic designer, Mike Mills’s sensibility is engaged by primal dialectics: documentary and narrative, high concepts and everyday realities, the personal and the political. His films, beginning with Thumbsucker in 2005 and carrying through 2021’s C’mon C’mon, explore the microcurrents within family dynamics, including the fictionalized portraits of his own parents presented in Beginners and 20th Century Women. As a filmmaker he’s known for sincerity and therapeutic nostalgia—Mills is especially occupied with the ongoing project of self-construction—but as a viewer, he’s drawn to works of formal daring as well as benchmark masterpieces. His native curiosity takes him in unexpected directions—across time periods, through genres and around the world. Experimental Danish documentaries, silent comedies, Czech New Wave surrealism, Hollywood classics: Mills finds transcendence in all of them.

A PERSONAL MESSAGE

my Film List

Click each title to discover our curator’s notes and where to watch

I chose Steamboat Bill, Jr. really for that last storm sequence, with the famous Keaton moment of the building falling over on him only to have him saved by the perfectly open window. That’s the most famous moment, but this sequence is full of innovative, hysterical, incredibly physical stunts and images. My favorite is Keaton’s hospital bed being blown through a horse barn—all the horses watching him travel incongruously through, Keaton maintaining that spiritual and subversively flat “How did I get here?” expression. An expression that points toward the confusion and chaos of life that we hold at bay, the inevitability of failure, failures large and small—mortality, really—that his humor, his entertainment also helps us hold on to. And he’s just so handsome.

{{ All Items }}The Cameraman has some of my favorite stunty things of Keaton’s. He’s such an athletic, camera-based guy. I feel like Stanley Kubrick and David Fincher—that strand of filmmaking—they must love Keaton?! And that’s not really my strand, but I do too. The physicality, not just of his stunts but of the camera. What inspiring camera ambition and inventiveness! And that they did what they did with what they had back then is so inspiring. I guess Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry are equally heirs of Keaton’s camera, no? That he had his own studio and would work loosely with scripts, really developing the story physically with his body each day, on his own terms—how inspiring and envy-inducing. And I think what Keaton is doing to masculinity, with that passive, vulnerable face that’s not fitting in, that is not in power, that is outside of community and, in ways, outside of entitlement? That is really interesting to me and gives me a lot of room as a guy. I love that in Keaton and Chaplin. They both revel in and celebrate and make entertainment and beauty out of the limitations of human control.

{{ All Items }}Anti-authoritarian absurdist humor is one of the best human inventions ever, if you ask me. The Marx Brothers, and their ties to vaudevillian history, are so culturally important and powerful, and I wish I was more like that. I love that their films are prewar and yet so modern in the way they delight in cutting through duplicitous cultural niceties. And the density of the jokes, the manic quality—it’s interesting to me, and educational, how contemporary that all feels.

{{ All Items }}This and The Cameraman are kind of a pair for me. I think about Chaplin and Buster Keaton all the time and their formation of our American film language. I feel like it’s still super relevant and there are many feats that they both pulled off, or that they created the ground that we filmmakers are all working on and living on. Modern Times isn’t just here to refer to silent filmmaking, physical filmmaking, physical storytelling, storytelling with very little dialogue. I know I make very “dialoguey” films, but I also think, How can I be more like that? How can I tell a story just with action? This is the harder art, the higher fruit. It’s really interesting the way that these films are intertwined with magic—magic as a performative entertainment—and that magic and film share so many key early innovators and a vaudevillian cultural background. Magic, as entertainment, and film are on the same team. And these films are also intertwined with the idea of outsiders, anti-authoritarian figures and stories. It points to a part of film history I’m honored to have anything to do with, the connection between cinema, anti-authoritarian–meets–Marxist-socialist vibes and humor, often absurdist humor, that works like a great Borges story or a Magritte painting to unravel, unscrew and desolidify the constructs we call normal, natural, business as usual. That's one of the quadrants of the flag that is filmmaking to me.

{{ All Items }}One of the best pieces of 20th-century art. Such bravado, such bravery. Fellini is telling a personal story flamboyantly and betting everything. It’s deeply cinematic; it’s visually rigorous and exploratory and deeply felt and unafraid. I love that combination. I think linear time is a construct that doesn’t quite exist. It exists in watches and clocks and history books, but in our human lives we’re constantly remembering things or worrying about things in the future. I think Fellini is a master at understanding the emotional dynamics of nonlinear time and emotional time and then finding ways to visualize it. Fellini is a very advanced soul.

{{ All Items }}Daisies is such a wild, beautiful film. Daisies and Something Different are both really gorgeous, very feminine, and you can just tell that the male “North Pole” is gone—and I find that really exciting. Daisies is just so virtuosic: There are so many gorgeous images, insane animation-editing, visually interesting in-camera tricks and a really wild, feral, unhinged playfulness to the whole thing. It has a really rad punk spirit. There’s the thinnest of narratives—you’re just involved in the energy of two women and their hijinks. It was an anti-war film, I believe, and she was banned for making it. I think it’s important to honor it somehow. Watch it and then we can talk!

Something Different, again, is a really brave and totally unique film that is told with virtuosic taste in shots, frames, blocking, editing, use of music. It’s two stories of two different women: One is a housewife who’s stuck in domestic oppression, and her story is intercut with a famous Czech gymnast and her life, her training, her husband, her trainer, getting ready for a competition—all of her stresses. And there’s no explanation of why it’s intercut. To me, the film is electric for having that inner eclecticism, inner hybridism. Why are they together? I guess it’s just a mystery or just such a brave move. It inspired me to use contrasting elements. I think if films contain a hybrid—say, using real documentary interviews within a narrative—it energizes the film via differences. And Chytilová knows that so well. Like a cook who knows how to throw in opposing tastes, knowing things that shouldn’t go together can be transformative. Like two plus two? All of a sudden they equal five, six, seven, eight.

{{ All Items }}Besides just enjoying this film—its lightness, its agility, how simply beautiful the shots are—I learned so much from the way it was made. The combination of trained and untrained actors. That it feels so real and unwritten, and it kind of is—that’s been a huge influence on me. I think Forman wrote a script but then only verbally told each scene to the actors: “You need this, you don’t want to give them that because X,” etc. I don’t do that personally, but knowing that’s how he made this effortlessly real-feeling film really helped me in my filmmaking.

{{ All Items }}Lovefilm is a love story and also about Hungarian history in the 1950s and ’60s. It starts in childhood and goes through the characters’ teenage years to their 20s—interweaving and overlaying small intimate details with big historical moments, all brought together in a very memory-based subjective language. The film deals with time and memory in such a beautiful way, with characters thinking back but also acting in the present. It’s so lyrical, mysterious, and features repetitions that accrue meaning through the film, and it dissolves the line between the intimate and the social. It’s a very personal story that ended up changing my cinematic life and really influenced my film Beginners.

Father is loosely based on Szabó’s own dad in World War II. It’s not afraid to just look at the smallest detail: They have a front gate with a metal ring on top of the post, and the son plays with it as he passes through. It’s a shot repeated a few times throughout the film—it’s a very banal but very personal shot that leaks out meaning and poignancy and truth in unpredictable ways. I feel like cinema is so good at helping us reexamine small, intimate but structural things like that—film can be so magic and uncanny in that way, when film language mimics subjective inner life.

Watch Lovefilm

{{ All Items }}

Watch Father

{{ All Items }}Besides just enjoying this film—its lightness, its agility, how simply beautiful the shots are—I learned so much from the way it was made. The combination of trained and untrained actors. That it feels so real and unwritten, and it kind of is—that’s been a huge influence on me. I think Forman wrote a script but then only verbally told each scene to the actors: “You need this, you don’t want to give them that because X,” etc. I don’t do that personally, but knowing that’s how he made this effortlessly real-feeling film really helped me in my filmmaking.

{{ All Items }}You may not have seen these next two films. They’re by Jørgen Leth, who calls them anthropological films, and they’re weird lengths. The Perfect Human is 13 minutes long, and Life in Denmark is also a short. They’re very strange films—they’re just expository presentations, but they’re so expository that they’re wild. They’re lyrical, strange and hysterical to me. So the narrator in The Perfect Human says: “Here is the human. Here is the perfect human. We will see the perfect human functioning. How does such a number function?” And it’s always repetitions, and it’s bonkers expository. I, for whatever reason, love that. It’s transformative.

In Life in Denmark you just see people—a family, an actress, a government minister, some poets, people sitting around naked—showing you what they do in Denmark. I don't know why I find that so deep or like an opening, like a thing I can get into and explore. I find films like this very lyrical—they do more than they say they're doing. And again, very simple. I like things that are deceptively simple—it seems so, but there are currents that aren’t announced at play.

Watch The Perfect Human

{{ All Items }}

Watch Life in Denmark

{{ All Items }}I adore Alice in the Cities. It’s shot by Robby Müller in black and white, and he really captures each place—and of course Wim Wenders is so good about place, location, evoking its history, and just the quality of being in a certain place, and then, I think, the emotions that can happen in that place. It really influenced my film C'mon C'mon. What’s transformative about Alice in the Cities is that it’s so small: The drama in it, the story in it—what happens between the characters is precisely, beautifully, micro and understated. So little happens and yet it remains aloft and captures my attention the whole way through. I tend to cry at the end of it: I find it deeply, non-manipulatively affecting.

{{ All Items }}This is a shorter film that’s, to me, so inspiring and representative of the strangeness and bespokeness of Varda’s career—all those formats and films that are not quite documentary, not quite narrative, in strange uncommercial lengths, all reflecting a vast curiosity and film flexibility. Her career is very anti-capitalist, and also not following the rules of the art-film canon. So Daguerréotypes is her street—it’s like a documentary of the ambience and the people on the street she lives on, and it’s also the sense of this particular brand of Paris life that’s going away, the sense of its being a part of Paris that’s not going to be there forever. I really like using cinema to try to hold on to something or explore something right next to you that will go away, or is gone, or that you don’t really understand but is worth sharing. This isn’t conflict-drama-transformation, all that kind of stuff. I find that a very Western, patriarchal cultural form that we’re all trained to want. I like that Varda’s work is different. I love not just her films, her presence in her films, but also the variedness of her career.

{{ All Items }}I studied at the Cooper Union where, if we had nothing to present, my teacher Hans Haacke would just show us stuff. So I learned about Arte Povera, Marxism in art, Fluxus—things that a Californian Santa Barbara public school kid just didn’t get to know about. One day he showed us The Way Things Go, and it remains one of my favorite, favorite, favorite pieces of art, filmmaking, human-made magic. It’s an exquisite physical dance of objects, all bouncing off each other. There’s no narrative to it, but I feel like it explains what movies can do, what cinema does: time-based art that loves motion and loves connections. There’s just something very punk about it—the whole spirit of it is very irreverent and it’s profoundly beautiful to me.

{{ All Items }}

I saw this when it came out, at that fancy theater on the Upper West Side. I was a graphic designer doing media studies, coming from a conceptual art background. I wanted to get out of the art world, into a more “popular” culture, and was looking for a way to use visual language to do that. I saw this film, with its inventive use of recreations and visualizations, which captures our inability to really get things right, or to be objective, and I found it transformative, beautiful. I left the theater wondering how I could learn how to be a filmmaker.

{{ All Items }}In this film people are dead and arriving in heaven—but heaven starts out as a rundown Japanese school building—and they have to pick one memory to bring to the afterlife, and a small, underfinanced but exceedingly conscientious film crew with a 16mm camera tries to recreate that one memory for them. Again, this film has influenced me a lot because I’m so obsessed with memory. A lot of the characters aren’t played by actors; they’re just civilians filmed in real time, unscripted, thinking of which memories they’d take. After Life has a very specific texture to it: a film with documentary and narrative practices going on, which I find really electric. There’s so much care in this film.

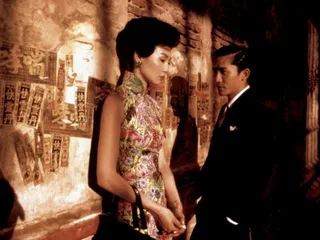

{{ All Items }}I watched this for three days straight on Vicodin and chocolate pudding after having my wisdom teeth out. It was a great time. The framing and lighting, use of slow motion, repetition of shots-actions-angles and one of the best role-playing scenes ever. It’s actually a very narcotic-feeling film to me, beyond my personal experience with it. The way he crosses the line with ease, that his cinema is image-based more than story-causality–based, that you often don’t know where you are, how you are, who you are, but you are happily swimming in his visual, sensual communication—more like a chant than a message.

{{ All Items }}I found this film so striking and powerful and mysterious, so beautiful, so deeply trusting a visual language and trusting human presence (human watching?) as a cinematic act that can replace the forward motion of “plot.” And I love that I could feel the presence of the person behind the camera and, in a wordless way, feel a connection between him and the people in front of the camera. Isn’t that wonderful? Also, kind of like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, it’s so much about our physical world, the spaces we live in and have emotions in and play out the possibilities of our lives in. The way the film could evoke the structural and historical powers that be in that place too.

{{ All Items }}

MY CREATIVE PROCESS

Exploring craft and influence

Galerie Originals

Mike Mills Origin Story WATCH

“Don’t wait for anyone to say you’re ready. Just start making things.”

RELATED MATERIAL

Essays, interviews and other connections

![The Artist is Present]() The Artist is Presentread

The Artist is PresentreadBeyond being the silent era’s hapless protagonist, Buster Keaton was an early avant-garde experimenter with the medium itself

By Louis Bayard

![In Defense of Silence]() In Defense of Silenceread

In Defense of SilencereadThe cinematic performances that speak the loudest don’t require any words at all

By Tim Griffin

![The Wim Wenders Experience]() The Wim Wenders Experienceread

The Wim Wenders ExperiencereadA celebration of Wim Wenders, featuring a long-form interview with the filmmaker, video tributes from Ethan Hawke and Mike Mills, and more

By Josh Siegel