The Artist is Present

By Louis Bayard

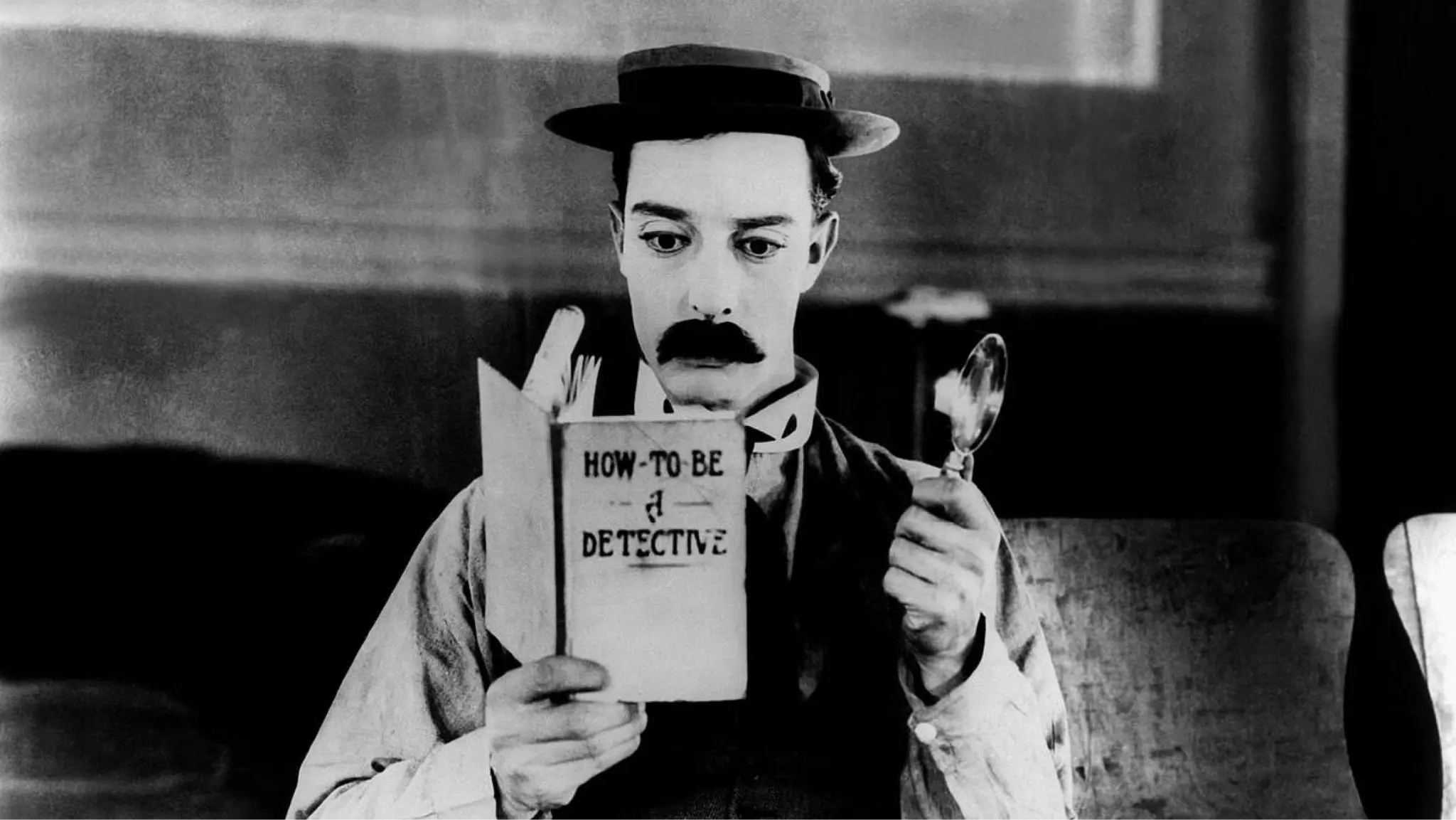

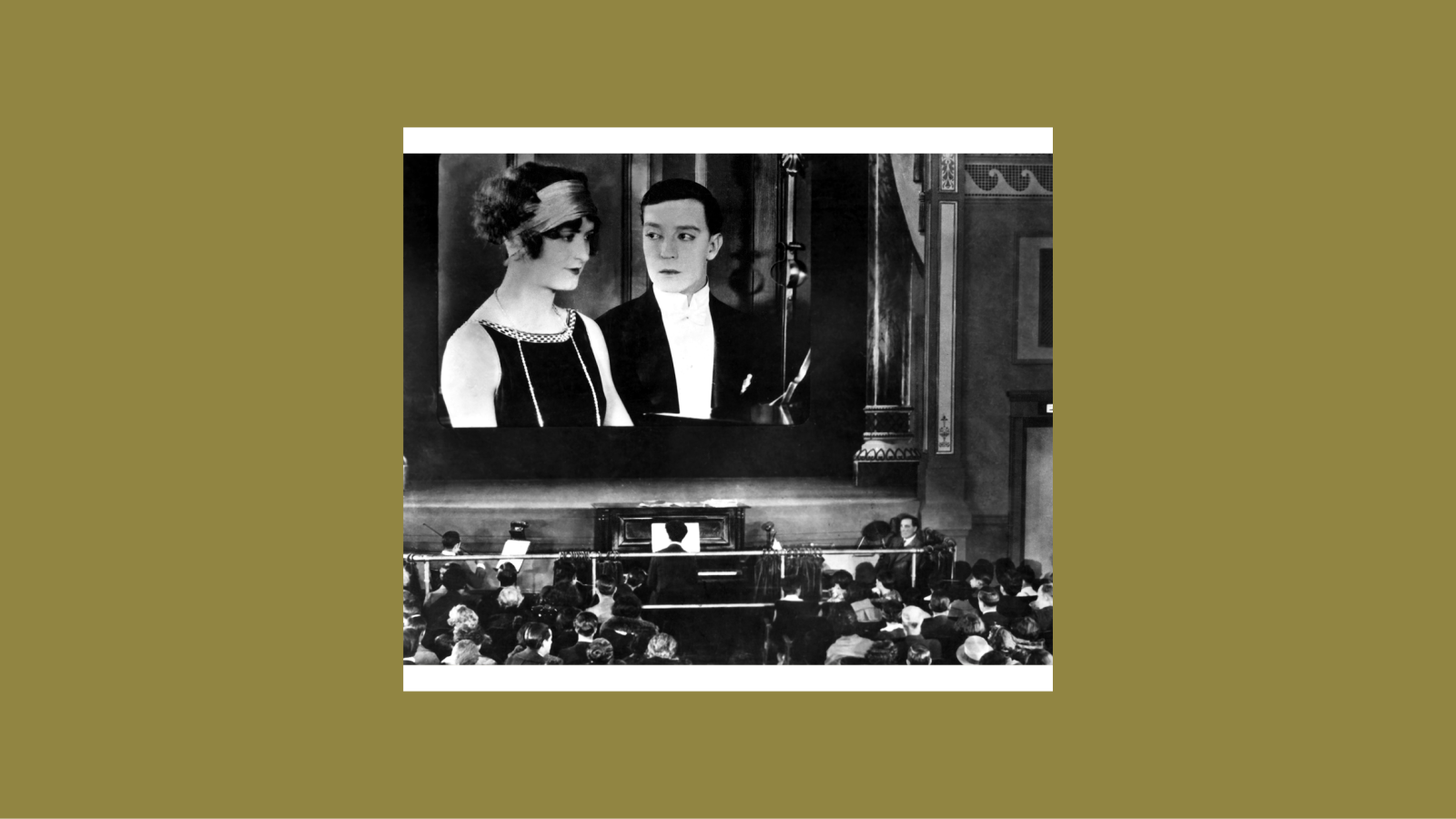

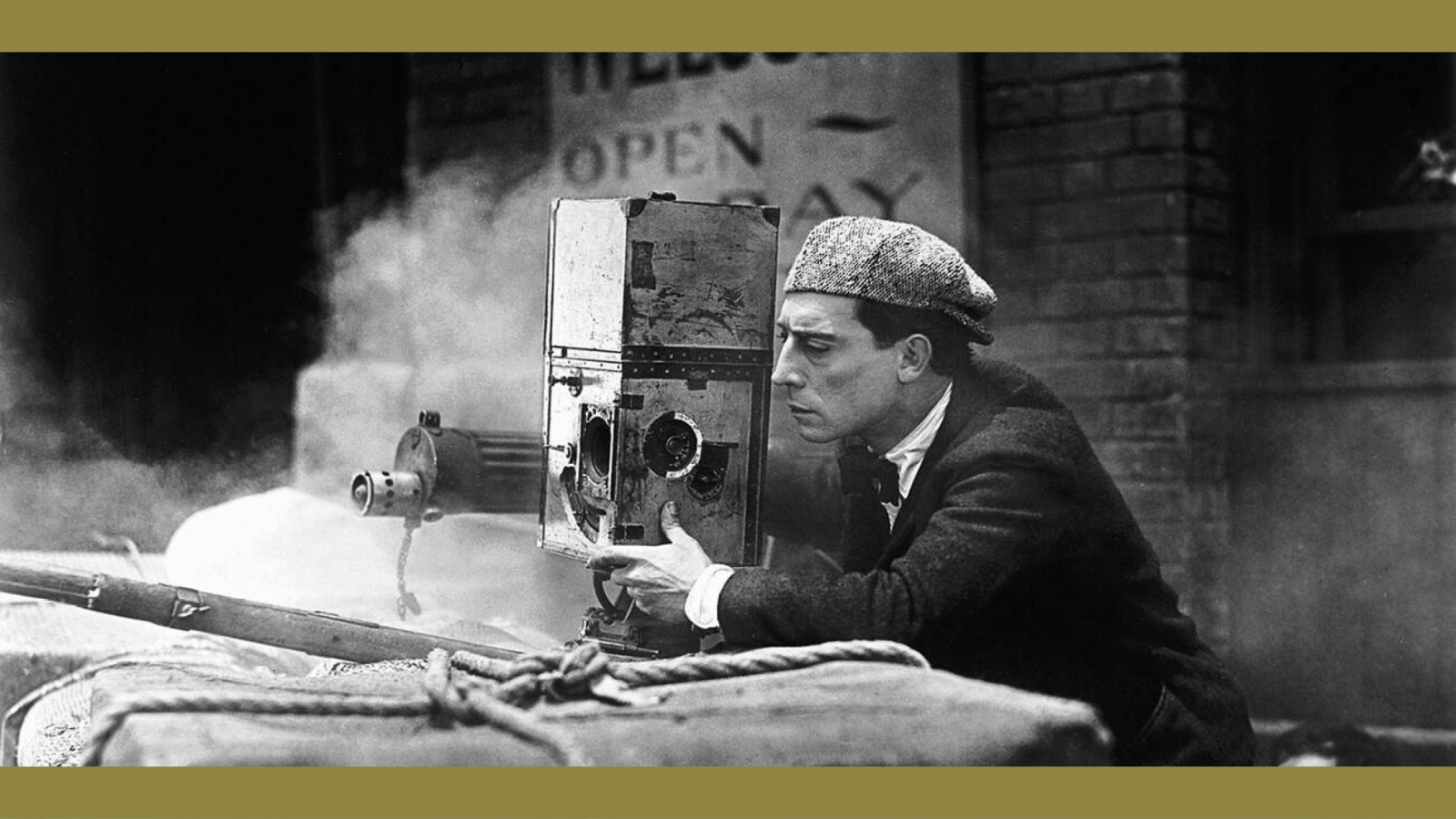

The Cameraman, dirs. Edward Sedgwick and Buster Keaton, 1928

The Artist is Present

Beyond being the silent era’s hapless protagonist, Buster Keaton was an early avant-garde experimenter with the medium itself

By Louis Bayard

August 25, 2023

He was born in 1895 in Piqua, Kansas, a one-stop railroad town his parents couldn’t wait to leave. A creature of vaudeville, he never had formal schooling, and at the peak of his worldly success, he considered himself nothing more than a gagman. If at any time of his life you had suggested that he was an artist or that his truest marriage was not to any of his three wives but to film itself, he probably would have rolled his lovely eyes.

Yet watching the silent comedies of his glory years, roughly speaking from 1920 to 1928, I can’t escape the feeling that they are, at some level, about the sheer vexed nature of making cinema, wrestling it into submission frame by frame. Three movies in particular—The Cameraman, Sherlock, Jr. and Steamboat Bill, Jr.—isolate what it means to be Buster Keaton, locked in a doomed romance with a medium no older than he was, a medium that, like a noir siren, lures him to his destruction.

From left: The Cameraman (1928), Sherlock, Jr. (1924), Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928)

If anybody could be said to be bred for motion pictures, then it would be Keaton. As soon as he was able to walk, he was a body in motion: the human cannonball in a roughhousing family act called the Three Keatons, in which he was quite literally hurled by his father from one end of the stage to the other, sometimes into the waiting arms of a stagehand. (His mother sewed suitcase handles onto his clothes so that he could be thrown with greater velocity.) It’s fitting, then, that his greatest films are preoccupied with how moving bodies react to other moving bodies—the aspiring bridegroom of Seven Chances (1925), for instance, chased downhill by vengeful women and rolling boulders.

But to get a full sense of Keaton’s own apprenticeship in the medium we come to The Cameraman (1928), in which he plays a New York City still photographer peddling tintypes for ten cents a pop. “They make fine ashtrays,” he assures one customer. To another he promises, “I’ll make them look just like you, Miss,” a pretty young woman who seems barely to understand that he’s taking her picture. She’s too busy waiting for her colleague, a newsreel cinematographer who rolls in on a tide of swaggering masculinity and long tripod—the New Medium in all its glory, driving mere photography into obsolescence.

The only way for Buster’s character to establish his masculine bona fides is to embrace the moving image, but his initial footage is marred by unintended kaleidoscopes and double exposures and reverse motion. Like all artists, he’s learning his craft through trial and error. Only when covering a Tong Wars outbreak in New York’s Chinatown does he find his balance: a motion-picture camera cranking forward and a human operator dragging himself out of harm’s way and—a first sign of true artistic sensibility—inserting a knife into a combatant’s hand to ratchet up the suspense. A director is born.

The house stunt from Steamboat Bill, Jr.

To track the implications of that ascendancy we travel to Sherlock, Jr. (1924), a 45-minute mid-career exercise in ontological fantasy that’s considered one of Keaton’s masterpieces. Buster is a “moving picture operator” who falls asleep while projecting a lousy romance called Hearts and Pearls. His dreaming self then wanders down the aisle of the theater and, in a startling moment that Woody Allen would later pay homage to in The Purple Rose of Cairo, bursts through the two-dimensional plane of the film screen. Taken aback, the on-screen characters thrust him out again, but in the next instant he is back. And an instant later, utterly alone, whipsawed by the film’s montage from the front steps of a house to a park bench to a busy road, then a clifftop, a lion’s den, a desert, a rock in the sea, a snowbank—all the outrageous possibilities that Hollywood art direction has to offer.

At last the bumbling protagonist finds a secure role within the film as genius detective, solving, in effect, the theft that his real-life self has been charged with. This imaginative transference allows him at last to gain mastery—not just over the on-screen villains, who come at him with poison and guns and a booby-trapped ax, but over the very medium of film, which now seems to bend toward the arc of his wishes. Billiard balls jump and detour; a human body divides and reassembles itself; two trucks, appearing from nowhere, plug the gap in a bridge just as a runaway motorcycle hurtles across it. Even in the climactic moment, when Buster’s getaway car literally slides off its chassis and into a lake, he repurposes it into a boat with a convertible top for a sail and gazes across the water as proudly as Horatio Nelson at the prow of a flagship. The lesson is clear: In cinema, a man may become master of his desires.

Sherlock, Jr., dir. Buster Keaton, 1924

It is here, though, that his filmic powers desert him. The car sinks, and Buster wakes in the projection booth just as his real-life sweetheart rushes in to declare him vindicated. They are free now to love each other, but Buster, shorn of the authority he had in the cinematic world, doesn’t know how to carry desire to its natural conclusion. So he transfers his gaze—where else?—back to Hearts and Pearls, studying and echoing the film’s lovers, only to see them become, through a single dissolve, vacantly grinning parents dandling babies.

Keaton learned very early in his career that audiences would laugh harder at him if he kept his expression grave—a trick that would earn him the nickname “the Great Stone Face.” Of course, his face wasn’t stony but beautiful and expressive, and in this final tableau, framed in the window of the projection booth, it tells us all we need to know about his character’s feelings. He’s been had. Not just by the promise of love but by the promise of film. Just as one image flows ineluctably into another, romance becomes, before a man can even change his mind, the slough of domesticity. It is the dilemma of not being in control of one’s own story, and Buster’s response—perhaps Keaton’s too—is the most philosophical one he can summon. He scratches his head as if to ask: How did I fall for that pack of lies?

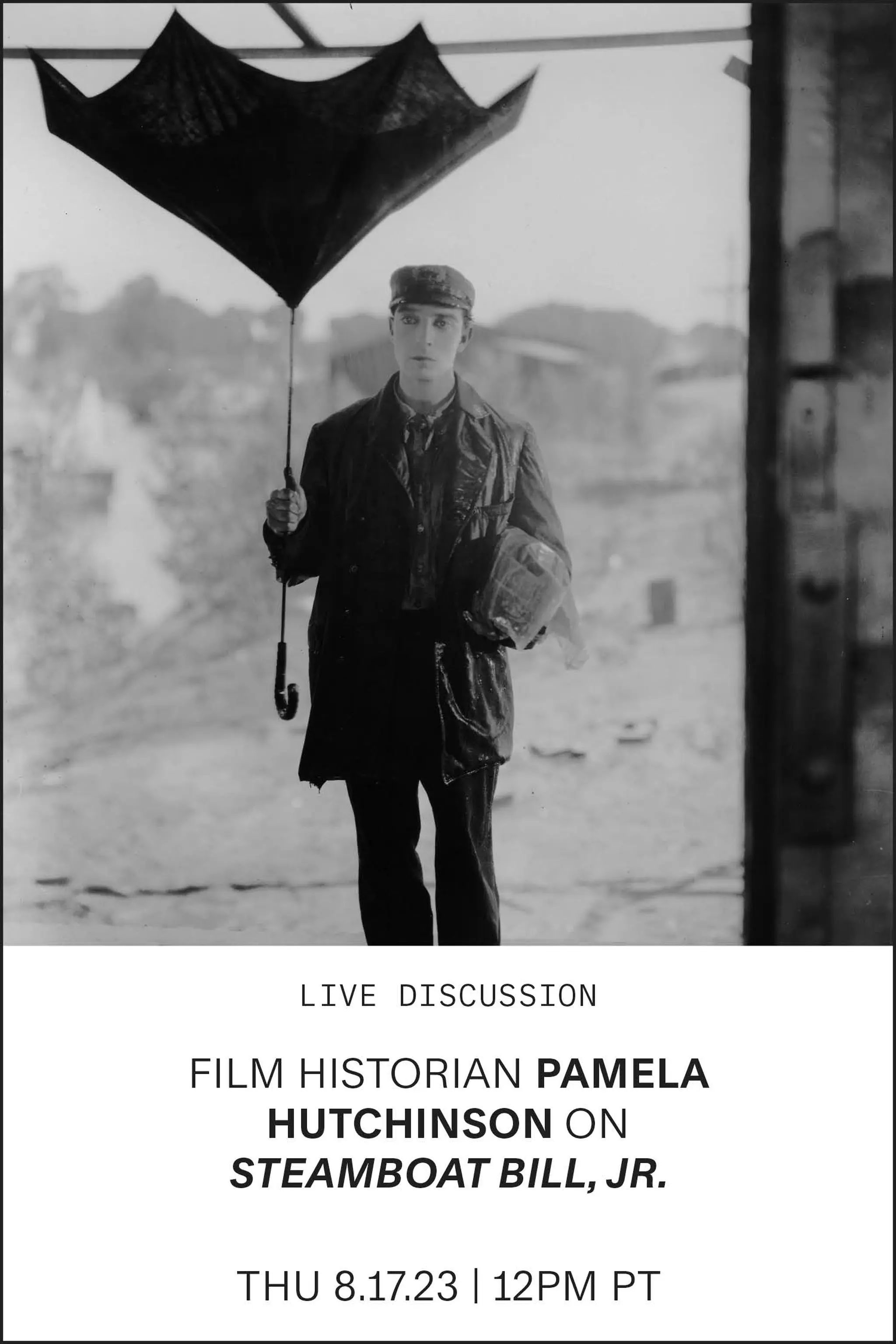

Steamboat Bill, Jr., dirs. Charles Reisner and Buster Keaton, 1928

The ultimate stage of Keaton’s love affair with movies is arguably expressed in Steamboat Bill, Jr., a 1928 film that represents one of his last hurrahs as an independent filmmaker. His character, an effete Bostonian with a beret and polka-dot bowtie and pencil mustache, is the despair of his über-masculine father, a steamboat pilot looking for a rugged heir. The son’s chance for redemption comes with an out-of-the-blue storm sequence that sets the town’s buildings collapsing like balsa models. One by one they topple—boats, a hospital, a prison—and because these squarish structures are so much closer to the 4:3 aspect ratio of silent film, it can feel as though the film is collapsing on itself.

In one of the most influential sequences ever committed to celluloid, a house front literally falls on top of Bill Junior while he’s looking down. By divine providence, he is standing in the exact crevice once occupied by a gable window. Keaton himself would later confess that he was “mad” during the filming of that stunt—the prop house weighed two tons—and his widow would suggest a death wish was in play, but when Bill Junior staggers out of the wreckage, his face expresses only a shocked resignation. The world of frames can no longer be controlled.

The Cameraman, dirs. Buster Keaton and Edward Sedgwick, 1928

This is a symbolic way of prefiguring what happened to Buster Keaton. Until Steamboat Bill, Jr., he had been ensconced in his own studio, able to make films entirely on his own terms, devising his own gags, working with collaborators he knew and trusted, spending as much money as he needed. (His now-classic Civil War comedy, 1926’s The General, proved a financial disaster.) But in 1928, his producer Joseph Schenck, bleeding red ink, lateralled him to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. In those number-crunching precincts, Keaton succumbed to what biographer Dana Stevens calls “the increasingly rigid laws of the movie marketplace” and, in a manner similar to Sherlock Junior, gradually lost control of both his films and his character.

“THE LESSON IS CLEAR:

IN CINEMA, A MAN MAY BECOME

MASTER OF HIS DESIRES.”

For a few more years, Buster Keaton remained a star, but as silent films gave way to sound he ceased to be a creative force. Two marriages ended bitterly and expensively. Alcoholism took hold. MGM fired him and by the late 1930s he was reduced to making cheap two-reel comedies for Columbia Pictures.

An even-keeled third wife got him back on his feet, and in the years after World War II Keaton would be lionized by critics and film festivals and by such cultural arbiters as Orson Welles and Samuel Beckett. For those who weren’t privy to his golden age, his many cameo appearances in everything from TV commercials to the 1965 Frankie and Annette camp comedy Beach Blanket Bingo were enough to imprint his mournful mug on their senses. He would go along for the ride, gratefully, but never again would he or anyone else trust him to helm a feature-length movie—to be both the protagonist of a cinematic universe and its all-powerful creator-god. Buster Keaton had seen what movies can do to a lover. And, like Steamboat Bill, Jr., who staggers away from the frame that tried to kill him, he would consider himself a survivor.