A Dream Job on Elm Street

By Daniel P. Coughlin

A Nightmare on Elm Street, dir. Wes Craven, 1984

A Dream Job on Elm Street

Daniel P. Coughlin

Interning for Wes Craven, the plant-loving, bird-watching sensitive soul behind some of the scariest movies ever made

October 1, 2024

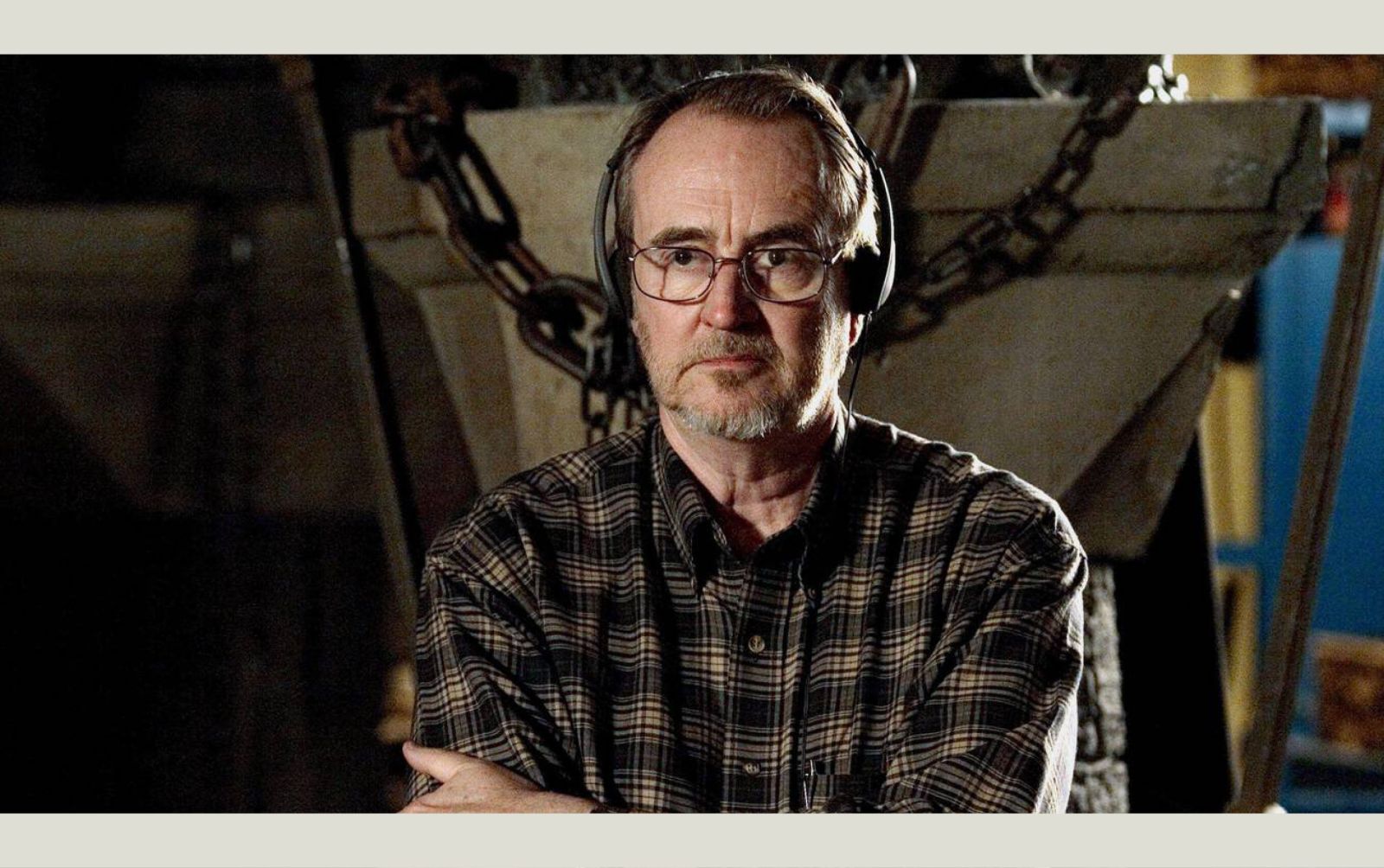

Wes Craven on the set of Cursed, 2005

When my film studies professor at California State University at Long Beach announced that filmmaker Wes Craven would be attending our class for a Q&A session after a screening of his film A Nightmare on Elm Street, I practically lost my mind. The auteur of the dark arts was a major hero of mine. I had religiously watched all his works growing up as a child of the ’80s (usually tuning in late at night after my parents went to sleep). A Nightmare on Elm Street, a horror classic that made a burnt, glove-bladed dream-stalker named Freddy Krueger a household name, was one of my all-time favorites and its director a cinematic icon to me. I approached my teacher to ask whether Craven ever hired students or provided internships. He responded with a cynical smirk: “Never hurts to ask.”

![]()

A Nightmare on Elm Street

![]()

Back home in my cheap apartment in downtown Long Beach, I revised my incredibly limited résumé. The year was 2006. I was 27 and a few years out of an enlistment in the U.S. Marine Corps. There was nothing on my résumé but military experience and three years of film school with a little experience working on the automotive reality show Chop Cut Rebuild on MAVTV. Basically, I would have to charm Mr. Craven rather than dazzle him with my bona fides. I wrote down a list of questions for the Q&A that I thought might catch his interest. Specifically, I wanted to ask whether societal exhaustion from the endless violence of the Vietnam War had influenced his first feature, 1972’s The Last House on the Left. As I was the only student in the class with military experience, I didn’t think anyone else would ask that kind of question. Craven’s films always played on our cultural psyches and fears. The Last House on the Left follows two teenage girls as they head into the city in order to attend a Blood Lust concert. Along the way, the girls run into a gang of sadistic psychopaths that have recently escaped from prison. The young women are tortured, sexually assaulted and brutally murdered. By the midpoint of the film you want to puke and are tempted to leave. But after watching innocence desecrated in such a horrific manner, an inner voice compels you to keep watching—you want redemption, justice, even revenge, which Craven supplies in the film’s second half. In keeping with its early 1970s origins, I found the villains’ increasingly gruesome tactics derivative of the Vietnam War’s sadistic violence.

Class started at 7 p.m. Craven arrived halfway through our Nightmare screening. I knew because whispers emanated from the back of the student theater. I looked behind me and there he was, a tall looming presence, 66 years old, dressed in black slacks and a sleeveless vest over a black button-down shirt. His signature white goatee curled at the chin. He looked pleased to be joining us. At this point, my nerves cranked into high gear.

When the film ended and the lights went on, the professor introduced our celebrated guest. Craven took the stage and waved. The professor started by asking a few introductory warm-up questions. Craven spoke of his troubled upbringing without an active father and of a complicated relationship with his religiously fanatic mother growing up just outside of Cleveland, and how it had led him into the loving arms of film. Unbeknownst to me, Craven had intended on getting into the romance genre (it was hard to imagine Craven’s version of Terms of Endearment). Opportunity shoehorned him into the horror genre when the maverick film producer Sean Cunningham gave him the directing gig on The Last House on the Left.

“I later found out that Wes’s hobby outside of work was bird-watching.”

Finally the professor opened the conversation to student questions, and nervously I asked him mine. He talked about the terrifying era of the Vietnam draft and the deep psychological impact of the war on American society, confirming that the horrors of that war did partly inspire the violence in the film. I followed up that question with one about the use of booby traps in his films. Many of his protagonists rely on booby traps for survival (think of Nancy mousetrapping her entire house for a final showdown with Freddy in A Nightmare on Elm Street, or the grieving parents turning their home into a combat zone at the end of The Last House on the Left). Later on in our friendship, I actually gifted Craven my Marine Corps booby trap guidebook, which I’d used during my combat training.

When class ended, I approached Craven at the foot of the stage. His eyes locked on me and he seemed to be asking for my assistance in getting down. I extended my hand, pulled a little too hard and dropped him on his butt. I was mortified. Luckily, he found my mishap amusing. Nerves revved up, hands shaking, voice trembling a little bit, I asked, “Mr. Craven, can I have a job?” With a warm and welcoming nod, he said, “We have an internship coming up. Go see Carly and give her your résumé.” On the spot, I made my way over to Craven’s assistant and co-producer Carly Feingold, who’d accompanied him to the engagement, handed her my résumé and asked, “What do you think my odds are?” To which she gave me a quizzical once over, smiled and said, “I’ll be in touch.”

I thanked her, took a picture with Craven and went home to watch one of his classics, 1991’s monstrous upstairs-downstairs take on the American family, The People Under the Stairs. A few weeks passed. Then one day I was at home working on an early draft of my own horror screenplay (one that would eventually become my first scripted film, 2007’s Lake Dead), when my phone rang. Although I was only clued in by the 310 area code, I somehow knew this was the call. Carly was on the other end, asking if I could come in for an interview.

I arrived at Craven’s office in Studio City. The office was simple, on the second floor of a three-story building on Ventura Boulevard, decorated with a lot of plants and contemporary artwork that gave the beige walls character. Craven/Maddalena Films consisted of roughly four offices and a breakroom. Tara Billik, an assistant at the time—now VP of feature films at the Jim Henson Company—conducted the interview. Shortly after it was over, I was offered the internship, partly, I suspect, because they were thinking about moving offices and my military appearance led them to believe that I could lug boxes up and down the stairs.

Left and center: The People Under the Stairs, dir. Wes Craven, 1991; Right: The Hills Have Eyes, dir. Wes Craven, 1977

On my first day of work, I discovered that Wes (as he was known to everyone in the office) was incredibly fond of his many plants. One of my jobs was to water them, put them in the sun—basically to not kill them. Being a Marine, I’m good at killing things, and all of Wes’s plants were dead within two weeks. My other tasks included answering the phones, restocking the refrigerator, cleaning and running errands. Wes popped in on the first day to say hello and gave me a small card thanking me for accepting the internship. The card had a photo of a small red cardinal on the front and inside he’d slipped a crisp hundred dollar bill. Being a broke college student, I welcomed the extra money. These cards usually came on Fridays, as Wes only visited the office once a week or so, mostly for meetings with filmmakers or to speak with his assistants or check on the administrative status of his then current project, producing the 2006 remake of The Hills Have Eyes. I later found out that Wes’s hobby outside of work was bird-watching.

The budget for Wes’s films was usually limited, but he never needed much money to make a lot of noise. The reactions he elicited from his audiences were equivalent to those of Scorsese, Spielberg or Coppola—strong feelings, not simply cheap frights. He was precise about his films and knew how to imprison you in a theater seat. And over and over he could take you to the edge of that seat. In all his films, Wes created brilliant chaos. I often wondered how much pressure he felt to deliver that chaos. Fans were always speculating about how he could top his last venture. After the success of The Last House on the Left came his original 1977 cannibalistic horror The Hills Have Eyes, a film about an all-American family taking off on a cross-country road trip straight into inbred desert hell. At face value, The Hills Have Eyes copies familiar slasher tropes. The ones to be expected. A small group of innocent folks become stranded, stalked and then plucked off one by one. But the film also cut through paranoias revolving around class, who we consider misfits and the unacceptable notion that the paths of certain groups shouldn’t cross. As it turned out, Wes’s inspiration for the film, as I recall from a lecture he gave, was a trip he himself had made. He happened to stop in a reclusive desert town for lunch/gas/coffee and had an uncomfortable confrontation with a hard-edged stranger who proceeded to antagonize him for his celebrity status. Wes, a kind, sensitive and understanding person who posed no physical threat, couldn’t scare the man off and felt he was in real danger. He bottled up that terror and vulnerability and later applied it to his second film.

![]()

The Last House on the Left, dir. Wes Craven, 1972

![]()

Heather Langenkamp in A Nightmare on Elm Street

After a couple of weeks of proving myself at the office, I was tasked with writing screenplay coverage—penning a structured synopsis of proposed scripts that came in for consideration. Cody Zweig, one of Wes’s producers, handed me a small stack of scripts and asked me to write five pages of coverage on each one. Reading horror scripts from established writers is a great education, and I doubled the workload. Sometimes I would read four scripts in a day. During my downtime, I would work on my screenplay for Lake Dead, and toward the end of my internship I found a buyer for the script. I attribute my time as a reader covering scripts to the success of my little movie. When Wes heard the good news, he took the entire office out for sushi on Ventura Boulevard to celebrate. It was also my birthday. While at lunch, Wes told me he was working on a script for a sequel to The Hills Have Eyes. The film revolved around a unit of Army National Guardsmen conducting training in the desert prior to deployment. The training led the unit into combating the nuclear-affected psychos in the desert. Wes asked me all sorts of questions about my military training. It felt unreal to be having sushi on my birthday and sharing script ideas with this person I admired so greatly.

Shortly after that, Wes had me over to his Hollywood Hills home, which had a Japanese-style irrigation system in the yard to supply his garden with nutrients. While there, he asked me to help him hide all his best artwork. His wife’s daughter from another marriage was flying in for spring break with her friends, and Wes didn’t want his valuable art collection getting “spring broken.” It was another surreal Wes Craven experience, a dream worthy of a cameo from Freddy Krueger.

Wes died from brain cancer at the age of 76 on August 30, 2015, three days after my son Kasey was born. I’d not known that Wes was sick and so it was sad to hear this information on the news. Fortunately, his body of films remains. Wes wanted to show his audience that there is a monster within us all. And in doing so, he was able to redefine the horror genre for a whole new generation, tackling almost every subgenre—from grind house to slasher to monster to psychological thriller—and transforming it into gold. And he did so while scaring the piss out of us along the way.