NASA’s Power Couple

By Will Chancellor

Above and Beyond

Will Chancellor

Can space films help us grapple with our cosmic demotions?

July 1, 2023

AUTHOR READS

Have you heard the epic love story of Ann Druyan and Carl Sagan? They were working for NASA, attempting to comprehend humanity’s place in the universe and bottle who we are in the ultimate time capsule. They combed the globe, compiling clips of thunderstorms, tribal greetings, Bach concertos, and whale songs for a Golden Record that would leave Earth in 1977 affixed to the side of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, hurtling into deep space at tens of thousands of miles per hour. Their hope was that distant recipients, hundreds of millions of years from now orbiting some other star, would be able to decipher all it meant to be a thing called human on a planet called Earth. Working together, they fell in love. As that feeling of love washed over Druyan, the creative director of this Interstellar Message Project, she recorded her brain waves at Bellevue Hospital and pressed them on the record, speculating that the intensity of her feelings for Carl might be legible to a future alien race. Sagan and Druyan remained together until his death in 1996, and the frequencies of her early emotions are transcribed onto those two golden discs that still drift into the distant dark. And even if no one ever gets the message, the act of putting together such a far-ranging testament to life forever changed the way we see our planet.

![]()

Contact, dir. Robert Zemeckis, 1997

The story of Druyan and Sagan’s romance is slated to be the subject of director Sebastián Lelio’s recently announced film Voyagers. But far less is made of the screenplay Druyan and Sagan were working on as the Voyager probes were shot from Earth. Imagine the two sitting in their living room in Ithaca, New York, their window overlooking a gorge, thinking about how lucky they were to be sharing immensity with another person, how improbable it is to connect with anyone at all in the vastness of the cosmos, and then capturing that gratitude in a script called Contact. They finished the film treatment in the fall of 1980 for Casablanca Filmworks; two years later producer Peter Guber took it with him to Warner Bros., but development stalled. Sagan, frustrated with the dysfunction of the Hollywood machine, adapted their screenplay into a novel. That novel was then adapted and rewritten by two new screenwriters (James V. Hart and Michael Goldenberg) into a new screenplay, which ultimately became the film we know today. Despite the film’s deviation from their original script, the fundamental idea behind Sagan and Druyan’s endeavor remains intact: Those who truly apprehend the vastness of the universe will find that the consoling wonder of existence is that we are able to connect with other beings, to make contact.

The movie Contact (1997), directed by Robert Zemeckis, opens with a staggering look at our place in the universe. Rather than the soaring grandeur of a string quartet or the regal horns that often accompany grand cinematic panoramas of space, we hear the Spice Girls’ “Wannabe” as the camera flies from Earth through a tangle of static. The pop of the ’90s transitions into New Wave as we near the moon, disco as we pass Mars. The camera remains focused on a vanishingly small Earth as the radio dial continues to scan back in time. The transmissions of the Kennedy assassinations orbit Jupiter; “Volare,” Dean Martin’s 1958 hit song, skates the rings of Saturn. As we approach the edge of our solar system, in the haze of the Oort cloud, FDR declares that December 7, 1941, is a day that will live in infamy—just before Hitler opens the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. We fly faster, far away from Earth, deeper in space and time. We glide through an elephant trunk of dust and gas in the Eagle Nebula, a formation known as the Pillars of Creation, a place where stars are born, and here Earth’s faintest, oldest broadcasts give way to the cosmic crackle.

By visualizing radio broadcasts flying into the immensity of space at lightspeed, Contact orients the viewer with the vast scale required to tell its story. When I watched this opening sequence as a teenager, it was the first time I realized that the unabridged chronicle of our electronic existence radiates outward forever. But after the music stops and the last dit of Morse code fades, Contact goes silent. For nearly two minutes we zoom out of the Milky Way, our galactic neighborhood of 400 billion stars, into the silence of deep space. Surprisingly, we back into another galaxy and recede through it too, back deeper into a field where galaxies are glittering gemstones, thousands and then millions, and then hundreds of trillions, until all is a glowing white multitude and a diamond-sharp static.

Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan in the 1990s

Through an elegant match cut, we learn that the light we had been following for billions of light years—and for the four minutes of this spectacular opening sequence—is sunlight reflected in the eye of an 8-year-old girl. Accompanying this image, there’s an audio match between the opening’s static and what young Ellie Arroway hears on her ham radio. Ellie diligently scans transmission frequencies until she makes contact with a fellow enthusiast in Pensacola, Florida. To her left, a map with a pushpin centered on Madison, Wisconsin, marks with blue string each person she has found in the fog of electromagnetic noise. We see a pivotal moment in Ellie’s development, when her principal occupation seems to be defining what constitutes far and imagining how far she might one day reach.

That night, proud of her most distant transmission yet, she asks her dad (David Morse) how far radio communication could extend. She asks if they can talk to China, or the moon, or Jupiter, or all the way to her deceased mom. She then asks if there are people on other planets—to which her father responds, “I don’t know, Sparks. But I guess I’d say if it is just us, seems like an awful waste of space.” Hours later Ellie is back at the radio, searching presumably for the people on other planets. Rather than admit defeat, she declares, “I’m gonna need a bigger antenna.”

Jump-cut to the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, where a grown-up, now Dr. Arroway (Jodie Foster, in an uncompromising performance that inspired a generation of women in science) stands before the world’s largest radio telescope. A research assistant asks, “What do you think, Dr. Arroway? Isn’t she a beauty?” To which Ellie responds with a smile, “It’ll do.” More than mere understatement, her response speaks to the scale at which she hopes to apprehend the universe. Her name itself, Arroway, confirms that this is someone with direction, sure, but also a wide, outward orientation that will define her life.

On Earth we’re so far from the center of things that it’s laughable. Most of us just ignore that special misery that arises when contemplating the profundity of a universal void and stick our heads back in the comforting muck of a geocentric world order. Think you’re a fully enlightened post-Copernican soul who knows in your heart of hearts that the sun is the center of the solar system? Try explaining a sunrise or sunset—or even the words sunrise and sunset. Who sips their morning coffee and imagines spinning counterclockwise into the sun? We understand the world through our senses, not our astronomical knowledge, and our senses tell us that the sun rises and falls. But that’s just the beginning of the problem. The sun was the center of the universe until about 1924, at which point we realized that there were many many other galaxies out there but, thankfully, our galaxy was still the center of the universe. This worldview lasted for about forty years, until we discovered that not only was the Milky Way not at the center but that there is no center. Everything has been flying away from everything else since the beginning of time. Lacking a spatial center of the universe, we had one whisper of solace: Even if there isn’t a physical center, there is a temporal center, an originary moment, a big bang. Well, it’s possible that we’ve now lost that comfort too. Perhaps our big bang was just one in an endless cycling of bangs and contractions. We may live in an accordion universe and—what’s even worse—our accordion universe may be one of countless accordions in a vast ensemble. Dizzy yet?

![]()

Everything Everywhere All at Once, dirs. Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert, 2022

This terror of an emptiness beyond comprehension is brilliantly articulated in this year’s Oscars-dominating, multiverse-spanning drama Everything Everywhere All at Once, cowritten and codirected by the Daniels (Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert). In the film’s exploration of near-infinite universes, accessible to an elect few who can spin the kaleidoscope of existence from one bright pane to the next, mother Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh) and daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu) eventually embody rocks. They temporarily reside in one of many realities where the conditions for life weren’t quite right. And so, two rocks, side by side, thoughts relayed in black and white text, contemplate a lifeless canyon in late-afternoon wind.

The mother rock apologizes to the daughter rock and says she feels stupid for ruining everything by attempting to control fate. The daughter rock assures her that we’re all stupid and misunderstand the nature of reality, saying: “For most of our history we knew the Earth was the center of the universe. We killed and tortured people for saying otherwise. That is, until we discovered that the Earth is actually revolving around the Sun, which is just one sun out of trillions of suns. And now look at us, trying to deal with the fact that all of that exists inside of one universe out of who knows how many.” In a film defined by abrupt shifts in context, this scene offers a moment of sustained contemplation and at the same time reveals the reason the daughter feels so lost: Every arbitrary choice, every ricochet of matter, might produce an entire universe existing in parallel to our own. The perspective itself invites nihilism.

What I’m trying to say, and what I think these filmmakers are also trying to say, is that we’ve been through a lot. Anthropologists make much of how the shift to heliocentrism rattled the psyches of our ancestors, but what is that to where we are now? None of these dislocations, none of the trauma of these cosmic demotions, has ever been processed. Although we pretty much all know how insignificant we are in space and time, most of us choose to live in the smaller, more human scale.

Contact is a story that directly confronts the largest scale imaginable, but it’s also the not-quite love story of two people who approach immensity with alternative conceptions. Early into Ellie’s stint at the Arecibo Observatory, she goes to a cantina and shares a beer with Palmer Joss (Matthew McConaughey). Father Joss (and here it’s best to imagine a full, 100 percent–humidity McConaughey drawl) is “a man of the cloth without the cloth,” a seminary school dropout and budding spiritual authority who’s in Puerto Rico to observe the intersection of hypermodern technology and traditional cultures. He sits at her table and offers Ellie Cracker Jacks. This box’s prize is a plastic compass, which he gives to her. She scrutinizes it and hands it back, saying it might save his life someday. In a movie of orientation, this compass will end up being a symbol of every discussion between the two—Ellie has her orientation in the stars; Palmer, despite his ostensible ties to the infinite divine, repeatedly attempts to keep Ellie bound to Earth, where a compass might be of some use.

“Perhaps our big bang was just one in an endless cycling of bangs and contractions.”

Despite numerous attempts to ground her, Ellie Arroway becomes history’s first interstellar adventurer. She travels through a subway system of wormholes to arrive at an alien world. On this heavenly exoplanet that resembles her childhood drawing of Pensacola, she speaks with a being who has assumed the form of her departed father. His message to Ellie is “You feel so lost, so cut off, so alone—only you’re not. See, in all our searching, the only thing we’ve found that makes the emptiness bearable is each other.” This is the same message Sagan and Druyan repeated ever since they met. This is the vestige of that original screenplay: The universe is terrifyingly vast and our role terrifyingly insignificant, but we somehow continue to connect. I imagine Sagan and Druyan were aghast at the idea of a scientist (Ellie) and a mystic (Palmer) finding something like love in the rewrite, but they probably also had to concede that, at the very least, Hollywood nailed an astronomer’s sense of scale.

That word scale has evolved from its original meaning of “ladder.” (Think of storming a fort, and it’s clear that a large-scale operation is something that calls for a really tall ladder.) This image of a cosmic ladder is hidden in the alien’s reply when Ellie asks what’s next: “This was just a first step. In time you’ll take another.” He says that interstellar contact proceeds in increments, echoing a line her father offered when she was a large-scale child operating a somewhat limited ham radio, “Small moves, Ellie. Small moves.”

When Ellie returns to Earth, her account is met with incredulity. National Security Advisor Michael Kitz (James Wood, in a bid to convince history that he invented mansplaining), yells that she’s delusional and demands that she admit the voyage never took place, that it was all an elaborate hoax. Dr. Eleanor Arroway, voice faltering and eyes tearing, replies to this smug fool, “I was given something wonderful, something that changed me forever. A vision of the universe that tells us undeniably how tiny and insignificant and how rare and precious we all are. A vision that tells us that we belong to something that is greater than ourselves. That we are not—that none of us are—alone. I wish I could share that. I wish that everyone, if even for one moment, could feel that awe and humility and hope.”

At one point in the film, Palmer asks Ellie when she first knew she wanted to be an astronomer. She relates a moment when she was 8, looking at the first stars of dusk with her father. She asks the name of the bright star shining just above the horizon and learns that it isn’t a star at all, but a planet, Venus. She laughs in relating her intellectual origins, and we can imagine her younger self laughing in wonder. And that’s the great hope, isn’t it, to be surrounded by immensity, to orient yourself with laughable distances and feel that you are not alone?

![]()

Contact, dir. Robert Zemeckis, 1997

At every turn Contact depicts immensity and tiptoes around the terror of the void. At its climax, it also shows how a person might react when standing on the very top of her ladder. Ellie travels to the distant stars she first saw through a telescope. And there, floating before a “celestial event,” she slips into an instinctual, primal laugh. Whether this was Jodie Foster’s decision or Zemeckis’s, it’s a nice reminder that the only natural reaction when staring down near-infinities is to laugh like a lunatic with stars lighting your eyes.

Two decades after pop radio kick-started Contact, Denis Villeneuve announced his Arrival (2016) with precisely the solemn cello and the thoughtful violin that the mind expects when sitting down before a cosmic spectacle. Yet as Max Richter’s gorgeous “On the Nature of Daylight” plays, we see first an empty lake house at dusk and then a maternity ward. Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams as a credible linguistics professor) sets the theme in voiceover: “Memory is a strange thing. It doesn’t work like I thought it did. We are so bound by time, by its order.” Where Contact attempts to orient us in a new conception of cosmic distance, and Everything Everywhere All at Once attempts to orient us in the multiverse, Arrival tries to break our strictly causal conception of time, the this-followed-by-that-ness of experience, and to replace those nibbles with a notion of time as past, present and future all taken in one bite.

A moment after Louise hands a nurse her newborn daughter, Hannah, swaddled in the aqua-and-pink stripes of a receiving blanket, she says, “Okay. Come back to me. Come back to me. Come back to me.” These lines are stilted enough to catch our attention, and when you’ve seen both Arrival and Contact over a dozen times, they recall the moment when Ellie is overwhelmed by the death of her father and pleads for him over the ham radio, “CQ, this is W9GFO, do you copy? Dad, this is Ellie, come back.... Dad, are you there? Come back.” But where Dr. Arroway seeks her father by bridging the vast distances of space, Dr. Banks seeks to accept and comprehend a tragic ending, which she can already foresee, by readjusting her time-scale.

For a “space movie,” there’s oddly little mention of space in Arrival. Instead, the film draws our focus on time and how arbitrary our particular way of apprehending it really is. The opening sequence of Arrival lasts barely two minutes, and we witness Hannah’s birth, an adorable tickle-gun fight on a lawn, an 8-year-old’s “I love you,” a pre-teen’s “I hate you,” an oncologist palpating Hannah’s young neck, Louise sobbing in a dark hospital hallway, and finally Louise tucking the blankets under her dying daughter’s arms as she sobs and pleads, “Come back to me. You come back to me.” The Max Richter music isn’t helping, and at this point we are either crying single solitary tears or are reduced to breathless crumpling wrecks.

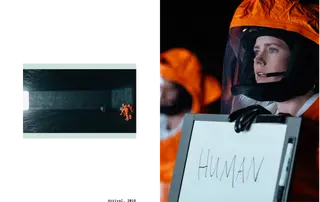

![]()

Arrival, dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2016

I think the opening sequence of Arrival is designed to be as soul-wrenching as possible: a precious 12-year-old daughter stricken down by cancer—as the father of a 12-year-old daughter myself, I struggle to even write that detail out. In the novella by Ted Chiang on which the film is based, Louise’s daughter is 25 when she dies in a climbing accident. The details of the cause of death might be significant too, but I want to focus on the effect of rewriting the story to give Louise less time with a child she knows she’s destined to outlive. Arrival suggests that the grieving process means inhabiting all the moments we remember of our life with someone as a way to distribute and dilute immense grief. What makes losing a child so unbearable is that every memory becomes overfilled with sorrow. By essentially cutting Hannah’s life in half, screenwriter Eric Heisserer distills the loss, emphasizing that some things are too much to bear in our limited time—unless we were somehow able to expand our notion of time itself.

After the Richter song fades, Louise declares, “But now I’m not so sure I believe in beginnings and endings.” In the next scene, the world discovers that 12 spaceships are hovering over Earth’s surface, each containing seven-legged aliens (Heptapods) who are willing to communicate with us through glass. In what is perhaps the initial dislocation in time, Louise and her physicist companion, Ian (a scruffy even when clean-shaven Jeremy Renner), can access the alien ship every 18 hours, forcing them to deviate from a normal day-cycle. As viewers we’re often left to guess whether they’re standing in sunrise or sunset. But the deeper reframe of time occurs when Louise deciphers the Heptapod language. When she learns to see reality as they represent it—as if a sentence could simultaneously be written from the left side with the left hand and the right side with the right hand, meeting in the middle—she gains the ability to remember the future just as clearly as she remembers the past. Louise can now see everything everywhere all at once. She sees her relationship with Ian ending as soon as it begins, but she nonetheless pursues it with great determination. She sees her life’s deepest grief, the loss of Hannah, before her daughter is even conceived. Perhaps her daughter’s birth is the less obvious arrival that the film’s title refers to; it is certainly the more painful departure.

For Louise, the ability to see time all at once expands the number of cubbyholes where she can store her profound loss. To a person reoriented with time at an all-encompassing scale, grief and joy intertwine from the beginning; she can grieve on the installment plan. Which brings us back to that opening. Arrival suggests that beginnings and endings cause our juddering lamentations and that if we were able to do away with them entirely, if we were able to stand “as a half-century-long ember burning outside time,” as Louise does in the novella, then maybe we could bear any loss just as we remember any joy.