Extra Terrestrial

By Lainey Wood

Extra Terrestrial

Lainey Wood

Finding connection between Arrival’s astral projections and the landscapes of Appalachia

July 5, 2023

There’s a moment toward the very end of Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016) where, for just a second, our gaze is tilted upward toward the needles of a pine tree. The background is arrayed into a canopy of soft-focus dots, while the branch carves a twisted diagonal through the frame. We are meant to be glimpsing this tree through a child’s eyes—a child we, by this point in the film, know has not yet been born and will not live to adulthood. This is how Arrival works, blurring the lines between past and future, forward and backward, beginnings and endings. The film is brimming with memory tricks, but this one works especially well on me because I’ve seen this shot before—ten years ago, in the backyard of a brick house in the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains.

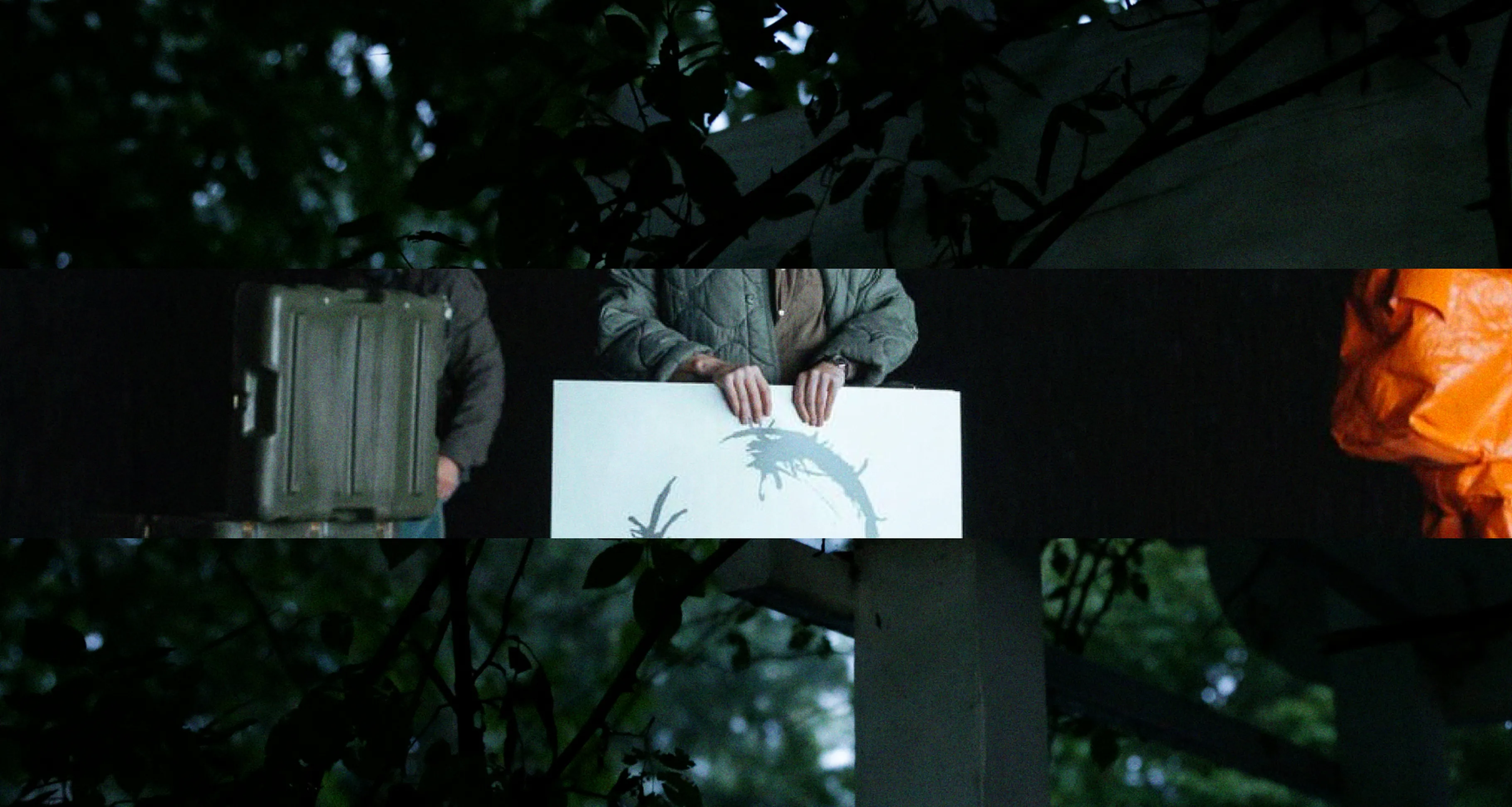

I am 17, the sun is setting, and I have taken a new camera out to see what it can do. In the half-light, I find the sharp point of a rose thorn silhouetted against the last flares of the day. The rain-softened wooden pergola that separates our driveway from the backyard transforms into a tangled green threshold of botanical shadows and lines. And as the mountains shift from their sketched lapis texture to a wide and limitless indigo, I look up into the maple tree and find a leaf where some creature has chewed out a near-perfect circle. As I experiment, I know that I am learning to see like the filmmaker I have just decided I want to become. What I don’t know is that I am also learning a language that is going to rearrange the very foundation of my life.

The main action of Arrival concerns a linguist’s attempt to decode an alien language, one that is written in elegant, circular inkblot logograms and defies most human logic. As Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) works to communicate with the aliens that have mysteriously landed on Earth, she begins to experience visions of a child, a little girl called Hannah. A voiceover at the beginning of the film preps us to understand that this is Louise’s daughter, who will die of an incurable disease when she’s only 12. What the film does brilliantly, though, is trick us into believing that Louise has already lost her daughter, that she is silently and stoically grieving while also trying to save the world. Somehow, what is actually happening is even more complicated.

When I moved to Los Angeles for college, it wasn’t the noise, or the traffic, or the concrete that most unsettled me. It was the darkness, or rather the strange distortion of it that we all still called night. The sky above my university campus glowed a lurid turquoise, leagues beyond the orange, globe-like streetlights that lit our paths home. The sky in Virginia had been a close thing, something that, on summer nights, seemed practically near enough to touch. Even when it was clear, the moon crisp and bright, the sky still seemed to lean down to get a better look at you. The landscape of California felt shockingly rigid and indifferent, and on those early hikes in the San Gabriels, my boots sending pebbles clattering into sunbaked canyons, an inarticulate grief clutched in my throat.

A key feature of the Heptapod language is the fact that it is “free of time.” The logograms are circular, and the Heptapods are able to produce them instantly. Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner), a physicist working with Louise, describes what that means in layman’s terms: “Like their ship, or their bodies, their written language has no forward or backward direction.… Imagine you wanted to write a sentence using two hands starting from either side. You would have to know each word you wanted to use, as well as how much space they would occupy.” As Louise begins to read and write Heptapod more fully, her sense of time starts to warp, and we realize that what we thought were flashbacks are actually visions of what’s to come. The pieces begin to fall into place, and we discover that Louise and Ian will one day get married and have a daughter, and that what will ultimately break them up will be Louise’s knowledge about how Hannah will die. This will be too much for Ian’s scientific rationality and he will tell Louise that she made the wrong choice.

When I lived in California, I struggled to articulate to others the loss I felt in being away from the landscape of Virginia. My grief was illogical—I returned home twice a year like many college students do, so I hadn’t really “lost” the landscape at all. Nor could I fully describe it as homesickness—I wasn’t just “longing” for home, I felt like my entire mechanism for making meaning of the world had been obliterated. It was as if I’d arrived somewhere and in the welcome brief they’d told me, By the way, no more vowels. No explanation, no grace period, no instruction in this new method of communication. What do you do with a language that’s been shot through with holes? How do you explain the totality of something that exists somewhere else to those who cannot feel its absence?

![]()

Arrival, dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2016

“Landscapes were the first human texts, read before the invention of other signs and symbols,” writes Anne Whiston Spirn in her book The Language of Landscape. For the most part, we in Western society have lost this ability to read the land, or forgotten that it was ever something we had to do in the first place. We navigate by GPS, check our phones for the weather, move through largely man-made environments tuned into man-made signs and symbols. Landscape has become inconsequential to us—we’ve reduced it to a view, a nice backdrop for a wedding, a quick panorama for an Instagram story. There is a paradox to the fact that we don’t tangibly, practically, in our everyday individual lives, need the land to survive anymore, except that of course we obviously do. In her book How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, artist and educator Jenny Odell argues for bioregionalism as an antidote to our multifaceted modern alienation from the land. “Ultimately, against the placelessness of an optimized life spent online,” she writes, “I want to argue for a new ‘placefulness’ that yields sensitivity and responsibility to the historical (what happened here) and the ecological (who and what lives, or lived, here).”

When you live in one place long enough, you start to recognize its patterns, exercising, perhaps subconsciously, those long dormant lectoral muscles. You learn when to expect a particular slant of light or cloud of fresh-blooming scent. You start to know it, in your bones, like a language. This is how I came to understand a grammar of another kind, where declensions are pools of light—saturated, languid, pale, storm-cast, rain-backed—enumerating the varieties within what Sally Mann, another Virginian, called the “radical light of the American South.” Our verbs here are tendrils and vines, and they tangle themselves in each other. Ivy, kudzu, honeysuckle, Virginia creeper—nothing in this place is ever really separate or still. Cherry trees in spring offer their courtly punctuation, boughs bent clear to the sidewalk under plumes of pale pink blooms. Tulip trees are a lesson in similes, their bug-like flowers scattered across the streets in early June. And the blues, oh the blues. They make a mockery of tense, of time. Buttery, baby, cobalt, midnight, chalk-dust—there are a thousand twilights in this place.

“We are so bound by time, by its order,” Louise narrates at the beginning of Arrival, and we as an audience don’t yet know how fully true this statement is. We tend to think that we know what time is and how it works. Time is countable, predictable, a resource we control—we spend time, make time, waste time—even as schedules and updates and obligations run us ragged. Time is also absolute and true; our phones sync themselves to “Universal” time (as determined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, appropriately governed by the U.S. Department of Commerce), which posits that the only time is the one broadcast by an atomic clock in Boulder, Colorado. Similarly, we like to think of time as resolutely linear, moving steadfastly forward from beginning to end. Our lives, our careers, which we have decided to measure in progress, demand it.

![]()

From left: Thorn Details by Lainey Wood; a still from Arrival

All of this is banal, pedestrian, except that in the grand scheme of human history and culture, our linear concept of time is the odd idea out. For most of human history, time was thought of as circular, linked to the movement of the stars, the changing seasons, the phases of the moon, women’s menstrual cycles. It was the Enlightenment, with its emphasis on rationality and scientific observation (and patriarchy) that ushered in the dominion of the mechanical clock. “Light was privileged over dark, the visible over invisible,” Jay Griffiths writes in A Sideways Look at Time. “The fascination with the visible meant that the clock, objective and visible machine of measurement, became privileged over the subjective invisible mystery of time itself.” Is it any wonder, then, that it is in the soft dark of a Virginia night that I feel my sense of time and space most transformed? That in the charcoal depth of winter, I can stand on a hill looking through the trees at the streetlamps and yellow squares of window light below and feel at once swallowed by the landscape and like the entirety of it lives right here inside my throat?

Every year I come home and things are different. New apartment buildings, a Wawa, a house in the field where I used to wait for the dog. This is inevitable, I know. What frightens me, though, is that someday I’ll come home and the honeysuckle will no longer measure the end of May, or the tulip trees will turn yellow in August, or I will have missed the last few years where you can still taste spring in the morning air. I said to a friend the other day—the first time I had voiced the fear so succinctly—“I’m afraid that I’m spending the last ten, fifteen years of recognizable climate and weather away from the place I love the most in the world.” “Fuck,” she said.

In the final, climactic push of Arrival, Louise enters the ship one last time, finding herself on the other side of the barrier where she asks the essential question: Why are you here? The Heptapod replies, “We help humanity. In three thousand years, we need humanity help.” They’ve come to offer their language to humankind, their alternate philosophy of time, as a tool, a weapon against some future calamity.

What do you do in the face of a coming disaster? How do you position yourself toward something that you know will arrive but the details or the scale of which are beyond your comprehension?

“What if, like the Heptapods, the tree was speaking to us, offering us something?”

If you’re Louise, you alter your comprehension as best you can. You try to save people, get them to talk to one another, to see differently. We already live with so many terrors, and I don’t want to encourage people to seek out another, but if the terror of the climate crisis hasn’t touched you yet, picture the thing you hold absolute dearest about a place, gather all your love for it and let it fill you, and then let it vanish, your love ringing through the empty space like a bell.

Returning to that image of the pine tree, I am struck by the way this shot—throwaway by the standards of some, replaceable B-roll—visually echoes the moment where Louise and Ian are given the final deluge of Heptapod logograms. The window inside the ship is flooded with tiny, overlapping circles of Heptapod script, the cumulative effect of which is not dissimilar to the bokeh in this shot. What if, like the Heptapods, the tree was speaking to us, offering us something? Just for a second, look at that still and consider each of those circles as language—what might they have to say? What might the light, shadow, color, hue, flickering movement of this tree, any tree, any landscape, have to say?

I may speak the language of Virginia’s landscape, but I am not yet a linguist of it, in a scientific sense. I don’t know when birds arrive and depart, or what many of them are called. I am startled by the discovery that the honeysuckle that has woven its way through my memories is actually an invasive species. I read up on the fall line, discover that the Scottish Highlands are part of the same original mountain chain as the Appalachians, investigate the history of the Blue Ridge’s characteristic haze. I tell my European friends about the Great Smoky Mountains, cite the affinity between Celtic and bluegrass fiddle, how both seem to leap and jump with the landscape. I try to describe weather patterns—I am a hit at parties—to people who have never felt a summer thunderstorm rock a valley to its core, never been caught in the half-tossed electric spell before the downpour, never seen the way the light glows green afterward, when the sky is still full of clouds but golden hour breaks through, scattering light down through the trees until the whole street is awash in an otherworldly hue.

For years I clung to these lines by poet Charles Wright: “Remembered landscapes are left in me / The way a bee leaves its sting, / hopelessly, passion-placed, / Untranslatable language.” I used to dwell on the absence that remembering requires, on the gulf that opened up each time I left Virginia. That space seemed insurmountable, both in making myself known to others and in reconciling life decisions that kept taking me away. Lately that space seems to be growing thinner, or perhaps I am just realizing that nothing is ever truly empty.

An depiction of the Heptapod language in Arrival

Arrival, despite the aliens and the geopolitical squabbling and the theorizing on language, is also a love story. A love story told in negative space. To use Ian’s metaphor when he cracks the mystery of the final logogram influx, “Stop focusing on the 1s; look at the 0s.” The Heptapods, the scramble to decipher their language and avert global catastrophe—are the 1s of Arrival. There’s no time for falling in love, and yet that’s what’s taking place between Louise and Ian, silently, in the space beyond what’s happening on screen. The love story here is everything that isn’t said. I find the poetry of that choice, in a film about language, absolutely breathtaking.

There is another line from the same Wright poem that strikes me now, “We have to choose which fear is our consolation.” My fear that I will lose this place, that it will change irreparably without my witness, that I have already experienced a number of unwitting goodbyes, is the same reason that I am so attuned to the sensory beauty of the world, that I feel color and light and space the way that I do. It is the thing that allows me to make what I make and be who I am. There is a devastating line in Megan O’Rourke’s memoir The Long Goodbye where she writes, “A mother is beyond any notion of a beginning. That’s what makes her a mother: you cannot start the story.” Virginia is my mother tongue, my motherland, my tiny known quantity of Mother Earth that my mother chose for us to call home. When I take my camera out and look up into her trees, I am looking into a story that begins so far beyond me that the only thing my fear can become is consolation. When I twist that lens and those exquisite circles appear, I am looking into my life, the whole of it, all at once. I am 17 and 27 and who knows, hoisting my child onto my hip to look through the viewfinder, telling her to pick a leaf and listen for what it has to say.

Sugar Hollow by Lainey Wood